- Shola flowers, Kolkata, 2019, Shola, 2880X1920

- Flower offerings, Murshidabad, 2019, 2880X1920

- Flower offerings, Howrah, 2019, 2880X1920

- Tea Kettle, Kolkata, 2019, 3449X1920

- Kalakand, Howrah, 2019, Milk and dry fruits, 2880X1920

- Bhar, Kolkata, 2019, Baked Clay,2880X1920

- Chiwda, Howrah, 2019, Rice Flakes,2880X1920

A message to you in English

and Hindi:

For quite some time, I have felt that traditional Indian textiles are a manifestation of fine art traditions in fibre. This notion gained weight when I attended an exhibition on the Baluchars of Bengal at the National Museum in New Delhi this year. One could be forgiven for not believing at first glance that these intricately woven repositories of the life and times of Murshidabad and Bishnupur were the work of human hands. As a textile designer, I had long wanted to witness the making of these woven wonders and resolved to visit the region.

I approached Kamalan to help me translate this resolve into a journey, and after due research and discussions, we settled on a nine-day itinerary that took me across the region to explore three prominent crafts: Sholapith, Masland mat-making and, of course, the Baluchars. The trip’s aim was to facilitate close interactions with the karigars (artisans) while delving into the historical and cultural context of these craft traditions.

My journey began in Kolkata, the capital city of West Bengal, which has retained a homely charm and a pace that is unusual for a metropolis. The streets were abuzz with people and I was pleasantly surprised to see that the city had survived the onslaught of disposable plastic and paper cups. Being a self-professed tea addict, I dove right into the lay of the land with sips of doodh cha, milk tea served in bhars (cups made of river clay baked on an open fire). Bhars are a part of living history, still shaped by hand and created by communities that have done so over generations. It is over endless cups of doodh cha that ideas and reform movements took root in the city of joy, influencing the cultural landscape of the country.

My local guide, Shubhroto took me first to the Dakshineshwar Kali temple, by the banks of the river Hooghly. It was an auspicious day, an occasion to witness the astounding variety of traditional textiles that would inevitably be on display. I searched longingly for an elusive Baluchari or Jamdani in the sea of devotees but had to be content with checked tant saris moving alongside traditional white and red gorod saris. The rest of the day passed by as a series of vignettes: crimson mounds of hibiscus as offerings to the Mother Goddess, the iconic yellow taxis and the endless possibilities of mouth-watering street food.

An early morning start proved to be invigorating as I set out for Murshidabad the next morning, passing through Bardhaman. This being Bengal, one had to merely glance out of the window to be met with an abundance of creativity. Homes painted in outrageous colour combinations seemed to stand in unabashed glee on either side of the road, with no two alike. Wooden banisters and ornate iron grill designs seemed to speak in a language of their own, conveying the unique persona of every home.

We arrived in Murshidabad before afternoon where I met my local guide Vishwakarma, fluent in both Hindi and Bengali and well-versed with local crafts. Murshidabad is an important centre for Sholapith, a craft that involves making objects from the soft stem of the shola plant to be used mainly in religious rituals. Given the abundance of the plant in the wetlands of the state, there is great diversity in the objects created in this tradition.

- Nandkulal Patto, shola artisan, Bishnupur, 2019, 1920×2880

- Shola Art, Chandra, Jiaganj, 2019, 2880X1920

- Shola Topor Frame, Bishnupur, 2019, Paper, Shola wood , 2880X1920

- Shola Art, Subhas Chandra Sarkar, Berhampore, 2019, 2880X1920

We headed to the workshop of Subhas Chandra Sarkar, an award-winning shola artisan who has been practising the craft for over four decades. It was here that I saw intricately carved peacock-shaped boats called Mayur Pankhi and topors and mukuts (ceremonial headgear for bridegrooms and brides) along with Ambari elephants and faces of Goddess Durga. In India, artisans practice their craft over generations where family members pass on the knowledge and skills to members of the next generation. However, in his case, I was pleasantly surprised to discover that he had taken up this craft out of his own interest, and learnt from a master artisan in Khagra. I bid goodbye to him, my thoughts occupied by the dwindling numbers of shola artisans, and whether there will be more Sarkars in the days to come.

We left the workshop to visit the Katra Masjid built by Murshid Quli Khan, a pivotal figure in the region’s craft history. As the Nawab who moved the capital from Dhaka to Murshidabad, he patronised families of weavers at the new capital, laying the foundation for a long line of craftsmanship of Baluchars that still exists today in the region around Bishnupur. The earliest Baluchars depicted scenes from the lives of the Nawabs and later expanded their language to include Indo-European motifs influenced by trade, and then further expanded their vocabulary as the weavers moved to Bishnupur to include depictions of Hindu mythology. Their elaborate pallus (end portion of a sari) with the kalkas (mango or leaf motif) and figures framed in ornate borders reflect the socio-political conditions of the region over the past two centuries.

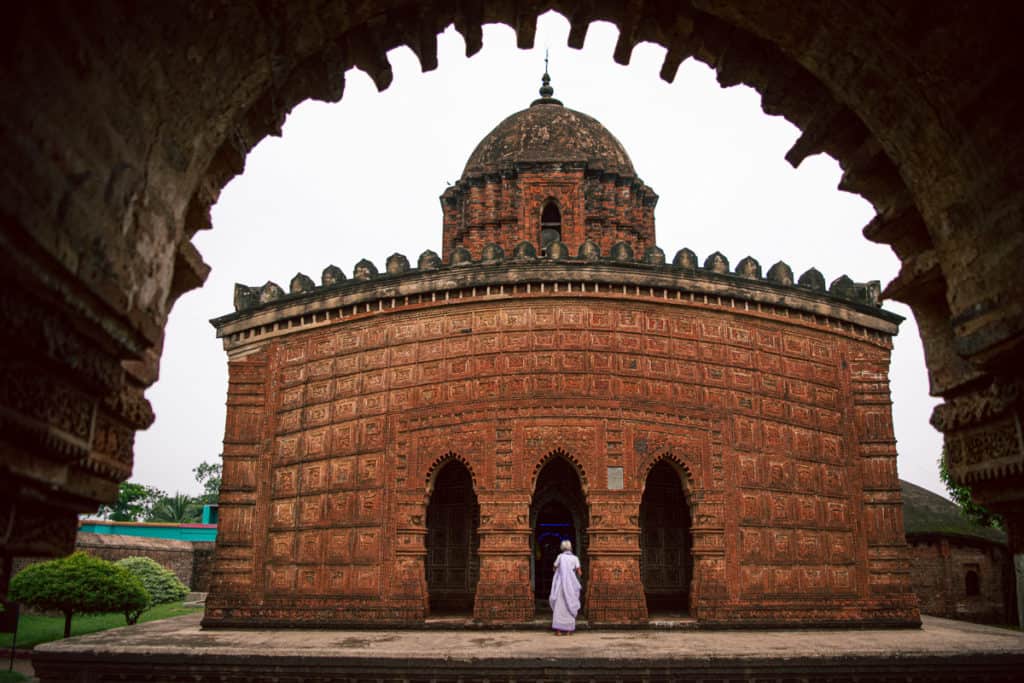

- Devotee at terracotta temple, Bishnupur, 2019, 2880X1920

- Figures on terracotta temple, Bishnupur, 2019, 2880X1920

- Close up of women figures, terracotta temple, Bishnupur, 2019, 2880X1920

- Swarnachari border close up, Bishnupur, 2019, Silk and Zari,2880X1920

The next morning, I set out for Bishnupur keen to experience this rich history translated onto the loom. The weaver’s colony was a cluster of pucca houses, huddled close to one another, filled with the rhythmic clanking of looms. Peering into a house, I saw a solitary weaver sitting in a pit loom that rose from the ground as a series of jacquard cards disappeared into the roof. The room reverberated with the movement of the loom and I craned my neck to see the weaver add the weft, shooting the shuttle laden with silk and golden thread. With each row of interlacement, a floral motif emerged upside down and I felt a peculiar mix of awe and jittery excitement, mingled with respect for the artisan.

Gazing at some of the unfinished saris on the looms, I could see influences of the famed terracotta temples of Bishnupur in the designs depicting scenes and figures from the epics. Belonging to the seventeenth century when the region was ruled by the Malla dynasty, these temples have fomented an environment of creativity for the many art and craft traditions that thrive in its vicinity.

- Baluchari jacquard loom, Bishnupur, 2019, Silk and Zari, 2880X1920

- Alok Laxman, Weaver of Baluchari sari, Bishnupur, 2019, Silk and Zari,2880X1920

- Charkha, Bishnupur, 2019, Iron and wood, 2880X1920

- Baluchari Pallav, Bishnupur, 2019, Silk and Zari, 2880X1920

- Aanchal of Baluchari on loom, Bishnupur, 2019, Silk and Zari, 2880X1920

- Baluchari on loom, Bishnupur, 2019, Silk and Zari, 2880X1920

I had to merely walk around the narrow pathways to spot looms embedded within homes. A peek into a window revealed a radiant green and blue Meenakari Baluchari; further along the path, I came across elderly women spinning resham (silk) onto bamboo bobbins. The entire community was involved in the craft—with one person spinning the silk yarn, another person dyeing it, and other people warping it.

I spent the rest of my time meeting other artisans, like the master craftsman Alok Laxman who rued the duplication of traditional designs by machine-operated units and in a break from his family legacy, had not trained his son in the craft due to poor prospects. I had mixed feelings as I called it a day. I was overjoyed to see Balucharis being made, but I was also concerned about the livelihood of the karigars and the dwindling demand for traditional Baluchars.

On my third day in Bishnupur, my local guide suggested that I visit some shola artisans and I made my way through narrow streets to meet artisans crafting topors by hand. Interestingly, the artisans here were using a traditional glue made out of atta (wheat flour), boiled for hours and then cooled to yield a gooey adhesive. In the streets, I could hear the faint buzz of machines and drills, and soon enough, I could see artisans working with conch shells to create bangles and carved decorative shells—mounds of white dust covered everything from the floor to the cobwebs. The craft is called shankha, after the conch shells, and the bangles are usually worn by married women.

The next day was dedicated to a visit to Midnapore, a rural centre for madur grass mat-weaving. We started early and Sameer, my guide for the day, informed me about the region’s significance in India’s independence struggle, being a hub of revolutionary activities since the mid-eighteenth century.

- Akhil Jana, dyed Masland Mat, Sarta, 2019, madur grass, 2880X1920

- Landscape, Murshidabad, 2019, 2880X1920

- Akhil Kumar Jana, dyed Masland Mat, Sarta, 2019, madur grass, 2880X1920

The drive to the village was exciting, with narrow streets flanked by ponds and paddy on either side. We eventually made our way to the house of Akhil Kumar Jana, an artisan making masland grass mats, also known as mataranchi. He belonged to a family of artisans and with the support of craft associations and the government, has made quite a name for himself. Greeting us at his home, he unveiled a masland mat. Its subtle two-toned pattern and arresting vertical borders drew one closer to the intricate details. He then stripped a grass stalk into two, showing me the tonal variations between the lower part of the stalk and the thinner, upper part that is utilised to achieve the two-toned patterns.

A heartening aspect of the masland craft is the prevalence of women weavers, a rare occurrence in a tradition mostly dominated by male weavers. Elaborating on the subject, Jana babu led the way to his workshop which was a big mud structure of several rooms, reinforced with local wood and bamboo. It is hard to describe the joy that washes over me every time I see a textile still on the loom, its maker hunched over with a calm and content look on her face. Grass stalks, dyed a darker shade of green, found themselves with their undyed cousins as the lady of the house worked patiently on her next piece. In her expert hands, each stalk danced in and out with precision, completing a row of interlacements. That, for me, was the image I wanted to carry back with me.

Evening fell and the familiar brushstrokes of green passed me by as I began my journey back home. I could not help but ruminate on the varied craft landscape of Bengal—how some of its traditions languished even as others thrived. Government support is vital but unless individuals become aware and cherish this intangible heritage, we cannot hope to see a restoration of this way of life for the artisans.

The clay bhars used across the state are proof that support and patronage at the grassroots level can help preserve craft traditions that are at once sustainable and part of living history. It is a painful reality that artisans are forced to choose between carrying on the legacy of handmade objects and leading a comfortable life by pursuing other professions. A lot has improved and a lot needs to improve but what left a lasting impression were stories of the artisans I met. As I left, I made a silent promise to return, for there were many stories yet to be heard in this land that has been the wellspring of numerous ideas and craft traditions.

Author

Swadha Sonu is a textile designer and marketer who has worked at the intersection of these fields for different brands. A long-time resident of Delhi, currently she channels her passion for craft and textile traditions of India through research, travel, and illustrations in her work at Kamalan, a cultural agency based out of India’s capital city. She looks forward to interacting closely with the diverse art and craft traditions of India to learn and spread the word about them and to translate her experiences into visuals and stories.

Swadha Sonu is a textile designer and marketer who has worked at the intersection of these fields for different brands. A long-time resident of Delhi, currently she channels her passion for craft and textile traditions of India through research, travel, and illustrations in her work at Kamalan, a cultural agency based out of India’s capital city. She looks forward to interacting closely with the diverse art and craft traditions of India to learn and spread the word about them and to translate her experiences into visuals and stories.