A relief sculpture depicting the worship of Buddha’s hair, with the inscription mentioning the ivory-workers of Vidisha above the panel at the southern torana (gateway) of the Great Stupa at Sanchi, Madhya Pradesh. Photograph by Anandajoti Bhikkhu, February 23, 2017. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Rachna Shetty from the MAP Academy presents an overview of craft collectives through the history of India that have shaped and been shaped by its material, religious and social cultures

Sanchi, c. first century BCE – c. first century CE

Travelling back two thousand years to the heart of the Indian subcontinent, one arrives at a landscape in motion. It is sometime between the first century BCE and the first century CE: at the crest of a hill in Sanchi, central India, there is activity around the enormous dome of the Great Stupa. Commissioned in the third century BCE by the Mauryan emperor Ashoka and believed to enshrine a relic of the Buddha in its core, it is now being expanded. Masons, sculptors and other artisans are hard at work, building a peripheral balustrade and a pathway for pilgrims to ritually circle the sacred monument. Along the path, four looming gateways are being erected to mark north, south, east and west. These ceremonial stone gateways, or toranas, each topped with three cross beams or architraves, will become iconic in Indian religious and visual culture for millennia — not least for their lushly carved surfaces. Their columns and architraves are being worked into elaborate sculpture panels by expert hands, depicting stories from the life of the Buddha, and scenes from his previous lives as narrated in the Jataka fables; as well as Buddhist icons, animals and deities of nature and fertility, like voluptuous, auspicious salabhanjika figures.

For the most part, as is the norm for this period, these craftspersons will remain anonymous. On one column of the south torana, however — just above a scene depicting the worship of the Buddha’s hair relic — some carvers leave a message: ‘Vedisa Kehidantakarehirapakam mankata’ — ‘Decoration by the ivory workers of Vidisha’. Coming from nearby Vidisha, not only have they extended their skills to some of the sculpture adorning this torana, they have also contributed to the project as donors. They are both artists and patrons. Today, this rare inscription by a craft guild gives us a glimpse into the rich, complex, often elusive world of collective art, artisanship and patronage in ancient India.

The Parrot Addresses Khujasta at the Beginning of the Sixth Night, from a Tutinama (Tales of a Parrot). Painting attributed to Daswanth, c.1560, Mughal India. Daswanth was one of the master artists of the Mughal imperial manuscript library and workshop. Image courtesy of The Cleveland Museum of Art.

Mughal India, c. late sixteenth century

About 1500 years later, a young man doodles on the walls of the Mughal workshop he is employed at. This is Daswanth, the son of a palanquin-bearer; while he is engrossed, he catches the attention of the emperor Akbar himself. The story will be recounted in the imperial chronicle of his reign, the Ain-i-Akbari by his grand vizier, the writer and historian Abul Fazl: how the impressed king invites Daswanth to be part of the imperial kitabkhana — the ‘house of books’, an integral Mughal institution that serves as a library as well as an atelier in which books and manuscripts are made and restored. Here Daswanth apprentices under the Persian artist Khawaja Abd al-Samad, and goes on to become one of the master artists of the Mughal court under Akbar, becoming renowned for his individual style and work. He contributes to major projects like the illustrated Tutinama (‘Tales of the Parrot’) and Razmnama (‘Book of War’), an illustrated translation of the Sanskrit epic Mahabharata into Persian. Yet, like other master artists of the Mughal court, he works in fluid and close collaboration with the many other artists and artisans in the kitabkhana, who each contribute their individual expertise and creativity to a seamless, cohesive endeavour.

Nearly two millennia apart, the urban craft guild and the Mughal kitabkhana are instances of artist organisations in the Indian subcontinent, which have taken different forms in different contexts through the region’s social, cultural and political history.

Dating as far back as a few centuries before the common era, artists’ and craftspersons’ collectives in the region have left an indelible imprint on the cultural and historical landscape of the subcontinent, whether as formal guilds, or kinship, caste or community networks, or as centralised production systems underpinned by direct patronage. Besides creating momentous temples and images that have withstood centuries, as well as textiles, jewellery and armour that are today housed in collections around the world, they served as patrons themselves, negotiated with local and overseas markets, and looked after the interests and wellbeing of their members. Perhaps most significantly, such guilds, networks and collectives were vital in fostering and transmitting knowledge — of ideas, techniques, materials, and their crafts’ associated rituals and philosophies — across generations and geographies, allowing it to be manifested in the crafts and living traditions of today.

Craft guilds in ancient India

The historical origins of guilds, both merchant and artisan, are associated with the rise of urbanism in India, which most scholars believe began around the 6th century BCE and unfolded in varying stages across India over the next few centuries. A strong agricultural base had allowed for the evolution of specialisation in crafts, and this was supplemented by an increase in trade as well as monetary systems like coinage. A variety of urban settlements emerged and flourished, from the nagara (fortress or town) and nigama (market or market town) to the mahanagara (a large city settlement) and the rajdhani (capital city). Craftspersons from the villages migrated to these urban areas for better opportunities as well as the abundance of high quality raw materials. Guilds are thought to have emerged with this, as artisans organised themselves to benefit from new commercial networks. Over the following centuries, as trade routes connected different parts of the Indian subcontinent and beyond, the significance of guilds also grew.

Buddhist and Jain texts from the early centuries of the common era, such as the Angavijja, Lalitavistara, Milindapanha and Mahavastu, and works of Sangam literature, composed in old Tamil and broadly dated between the third century BCE and third century CE, reference several types of craft workers, from weavers, ivory workers, goldsmiths and masons to garland makers, chariot makers and perfume makers. The Jatakas, Buddhist fables from between the 4th century BCE and 2nd century CE about the previous lives of the Buddha, mention communities specialising in various crafts and practices, each occupying a different village or quarter of the city. The ancient settlement of Kapilavastu (in present-day Nepal) is believed to have had guilds of goldsmiths, ivory carvers, stone carvers, oil pressers and winemakers, among others. Records of the nuances and differences of such organisations appear in ancient literary works.

Beyond guilds: Collectives and social organisation in the medieval and late medieval period

In India, the nature of artist organisations was more layered and complex compared to a medieval European guild, which had its foundations in shared systems of training and professional practices and goals. Guilds similar in function and structure to their European counterparts did exist in ancient India — a few surviving even until the nineteenth century — characterised by apprenticeship and training, established standards of technical quality, collective bargaining, and engagement with the market. However, in India such functions have not necessarily been confined to formalised guild structures alone — in the medieval and late medieval periods, they were also performed by familial, kinship and community networks or patronage-driven collective groups.

The historians Romila Thapar and KK Thaplyal state that by the early centuries of the first millennium CE, the structures of shrenis or guilds had formalised into jatis or occupational sub-castes. Derived from the Sanskrit ‘jata’ meaning ‘born’, jati denotes a narrow categorisation or subcaste based on birth, which determines individuals’ social standing and societal relationships in fluid, complex ways. The jati grouping often coincided with occupational divisions — which were increasingly established as hereditary under the Brahmanical varna or class system — and maintained cohesiveness through endogamous marriage ties and a strong geographical rootedness. To effect a change in their social identity, a jati would have to collectively move to a different place as well as a different occupation. Professional skills, practices and knowledge were transmitted within such family and jati units. For artisans of diverse kinds, such hereditary occupations and kinship groups formed a system of stability and support.

Enmeshed within these systems of organisation, says Thapar, were the objects of production themselves — that is, what an artisan group created also mattered in determining its identity, status and influence in society. She lists some of the attributes that had a bearing on the artisan’s, and by extension, the community’s, standing in the wider social and economic context: the function of the object created — whether it was practical or aesthetic or ritual; how it was consumed — whether personally, or via sale in the marketplace; and sometimes, the status of the patron who commissioned it. She notes how in ancient India a chariot-maker or a carpenter working for the affluent enjoyed greater social prominence than an ironsmith who made tools and armour, to be used by other workers or soldiers. Carla Sinopoli, in her study of the craft industry of the Vijayanagara empire (fourteenth–sixteenth century CE), examines how potters, who primarily made household goods and were part of a rural economy, had a lower social and economic standing than weavers, who manufactured textiles that were important not only for temple rituals and elite consumption but also in the context of trade.

Place, too, was important. Most historic artisan organisations have been predominantly based in urban settings, and artisans here remained distinguished from their rural counterparts for the reasons mentioned above. Even within urban settings, where varied and influential patronage was available, the specific nature of the product and patronage differentiated the status of artisan groups. For instance, a metalsmith creating ritual icons for a temple or employed by a court-patronised workshop enjoyed a higher social standing than another metalsmith in the same city commissioned by a less influential patron.

Shaping society: Guilds in culture and patronage

Guilds were composed of members who practised the same trade or profession. Historically, membership of a guild was not necessarily hereditary, in that some members did not follow a hereditary occupation, and membership did not always map rigidly along caste lines. They were hierarchical organisations headed by individuals; ancient Buddhist literature uses the Pali term jetthaka for the head of a guild, and the Sanskrit antevesika has been used to refer to apprentices who received training in the guilds. Guild heads, as leaders of sizable organisations that had their own insignias and flags, held considerable power and prestige — some texts mention them being a part of a ruler’s entourage.

The guild as an institutional framework held significance beyond simply the aggregation and providing of skilled labour to a project — scholars have discerned the role of craft guilds both in the lives of their members and in the context of the broader trading sphere. In addition to training artisans in a craft, guilds ensured reliability and accountability by setting standards of quality as well as prices for their services and products. Members who did not meet the standards or did not comply were often fined; these served as an additional source of income for the guild. As quasi-judicial systems for their members, guilds sometimes extended their powers to arbitration in issues concerning members’ familial lives.

As socially and economically prominent bodies, craft guilds were also enmeshed in the system of social and religious donations. They used a part of their profits to contribute towards the maintenance of watersheds, halls, tanks and gardens, and towards helping the poor. Vidisha’s ivory carvers are an example of this form of patronage, contributing to a part of the sculptural programme at the Sanchi stupa as both artists and donors. As both, they were only one among several hundreds of individuals and groups who enabled the building and expansion of the Sanchi complex as it stands today. The Buddhist rock-cut cave monasteries that dot the hills of the Western Ghats similarly reveal the patronage of monks and nuns, royal families, as well as professional artisans, not only through inscriptions but also as suggested by their location along major trade routes of the period.

Another example of religious patronage by craft guilds is evidenced in fifth- and sixth-century CE inscriptions found around the ancient city of Dashapur (present-day Mandsaur or Mandasor) in west-central India. Some of these describe the migration of a guild of silk weavers from Lata (in present-day Gujarat) to Dashapur, then a significant Hindu religious centre, and their patronage to the construction of a temple dedicated to the Sun deity Surya. They also funded its repairs and maintenance a few decades after its consecration.

In addition to functioning as patrons themselves, artisan guilds even served a bank-like function. They received endowments as deposits from individuals or entities, and provided interest on these, used on the donor’s behalf for patronage. Scholars cite instances where patrons provided clothing, meals and medicines to monks and nuns of monasteries using the interest accrued from their investments with guilds of weavers, bamboo workers and oil millers. In such cases, terms would be laid down, stating that only the interest on the principal sum could be used for the charitable deed of the endowment.

- The jagamohana (hall) within the Konark Sun temple complex, Odisha, India. The construction and execution of such vast complexes would have brought together several hundreds of specialist artisans, who worked in guild-like groups. Photograph by Hindol Bhattacharya. November 8, 2007. Image courtesy of Flickr.

- Relief sculptures at the Konark Sun Temple, Odisha, India. Photograph by Hindol Bhattacharya. November 8, 2007. Image courtesy of Flickr.

- Reliefs from the Konark Sun Temple, Odisha India, representing the chariot of the Sun God. Photograph by Phadke09. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Clues in the stone: The makers’ signatures

The caves of Ellora in present-day Maharashtra are home to Hindu, Buddhist and Jain monuments carved into the rock, an endeavour known to have begun around the sixth century CE, and one that would have involved elaborate planning and division of labour. From a stylistic analysis across sculpted dvarapala (door guardian) figures in some of the early caves, the scholars Deepak Kannal and Kanika Gupta have identified the work of a single guild, suggesting the specialisation of guilds even to particular genres of images. They also mention the probability of a central authority guiding the work across groups of such specialists in a large project.

From this period onwards, India saw a flourishing of religious architectural patronage. While traditions of rock-cut architecture from the ancient era continued to flourish, hundreds of new free-standing stone temples were constructed across the Indian landscape. Patronised by wealthy and powerful donors including royal families, officials and merchants, these were projects that brought together diverse professional groups. Each group was engaged to carry out a specific role of expertise in the artistic and architectural processes — from designing plans and sculptural layouts to cutting and dressing the stone, carving and woodwork, shaping the central icon, and painting murals. Guiding the efforts of multitudes of artisans were figures such as the sutradhara (architect), the head stone mason and the chief sculptor.

There is evidence to suggest that organised guilds, made up of individual artists as well as family units with several generations working together, would have been a part of such large-scale projects. In his analysis of a palm-leaf manuscript that describes the construction of the thirteenth-century Sun Temple, Konark (in present-day Odisha), the historian George Michell states that artisans and labourers would have been organised into guild-like structures, which would have regulated the hours and wages of their members, and the costs of completed work.

Individuals or guilds of highly skilled architects and sculptors find relatively few mentions in texts from ancient India that list many other craftspersons — owing perhaps to their itinerancy and lack of formal organisation, according to the historian RN Misra. The medieval and late-medieval period, however, yields inscriptions that credit such specialists.

Some examples of such inscriptions are found in present-day Karnataka. At the eighth-century CE Virupaksha Temple, one of the largest in the Pattadakal temple complex where kings of the Western Chalukya dynasty were once crowned, is a carved inscription naming Sri Gunda as the architect of the structure. Alongside the various epithets praising him, the inscription also mentions the term ‘Sarvasiddhi acharya’. The term appears again at the Papanatha Temple in the same complex, on an inscription crediting the architect Chattare Revadi Ovajja. While perhaps used as an epithet of praise — translating variably as ‘preceptor’, ‘venerable one’ or ‘architect priest’ — some scholars believe the term may represent a guild of architects to which both Sri Gunda and Ovajja belonged. At a quarry site near Pattadakal, which may have provided the stone for the temples, one inscription names two members of a sanghata or guild of quarrymen, while others show symbols such as a conch-shell or a trishul (trident), which scholars suggest may have been identification marks of craftspersons or guilds.

Epigraphical signatures become much more common in Hoysala temples commissioned in Karnataka from the 12th to the 14th century, with master sculptors inscribing the stone with not only their names or guild names but a series of self-proclaimed titles and claims of supremacy over other sculptors. Among these, the phrase ‘Sarasvati gana dasa’ (‘Servants of Sarasvati’) appears across a number of temples, leading scholars to suggest that the sculptors may have belonged to a guild of that name or were associated with a temple dedicated to Sarasvati, the Hindu goddess of learning and the arts.

The Brihadishvara Temple in Thanjavur, Tamil Nadu. Even after a temple was completed and consecrated, a host of people, from sculptors and smiths to dancers and musicians, played an active role in the daily and festive calendars of the temple. Photograph by Rainer Voegeli, December 30, 2012. Image courtesy of Flickr.

From the temple to the world: Artisan settlement, identity and trade

The temple was not only a place of worship or a symbol of patronage. It functioned variously as a social space, an economic entity, and as the crux of the local economy — as the development of temple towns in southern India between the 9th and 16th centuries shows. The detailed inscriptions at the Brihadishvara Temple, Thanjavur, completed in the eleventh century under the patronage of the Chola ruler Rajaraja I, provide an example of how large temple complexes required the services of professionals ranging from sculptors, smiths, woodworkers, garland makers, oil suppliers, dancers and musicians, priests and watchmen.

These large temple complexes were physically, economically and culturally at the heart of a temple town. The streets surrounding these complexes came to be occupied by and identified with the various artisan groups who settled there, specialising in providing services to the temple as well as to the court, the upper classes and the market in general. The temple directly employed master artisans for various specialised tasks, such as carrying out engravings to record temple activities; artisans were also engaged in other crafts for the temple, court and trade, often in workshop systems with apprentices. Wood carvers worked on temple chariots, metal workers crafted processional idols or ritual objects like lamps or armour, master goldsmiths supplied jewellery for use in the temple or made objects for courtly consumption, and sculptors made statues of deities, hero stones or portraits of royal donors. Some of these occupational groups forged a community identity for themselves, identifying themselves as belonging to the clan of Vishwakarma, after the Hindu deity of craftsmanship, and elevated their social status through economic success. These groups were goldsmiths, brass-smiths, carpenters, masons and blacksmiths, and they were known as Kammalar in Tamil Nadu, Panchanamuvaru in the Andhra region, and Panchala in the Karnataka region.

In the tenth century and later, the region corresponding to present-day Tamil Nadu and the broader southern India region was also closely linked with the maritime trade that connected peninsular India to the Red Sea region in the western Indian Ocean, and Southeast Asia to the east. With cargo ranging from foodgrains and cloth to elephants and horses, and from gemstones to wood and perfumes, this trade was facilitated by influential merchant guilds. Among them were the Hindu merchant group Manigramam in Tamil Nadu; Anjuvannan, a group of Arab merchants in the Malabar region; and Ayyavole, also known as Disai-Ayirattu-Ainnurruvar (‘The Five Hundred of the Thousand Directions’), a merchant group from Aihole in Karnataka, who also became facilitators of religious patronage in Tamil Nadu, handling endowments of land and gifts, and constructing temple structures.

- Markets around Srirangam temple, Tiruchirappalli, Tamil Nadu. Large temple complexes like Srirangam were at the religious and commercial heart of temple towns, and even today, the streets around the complex are occupied by markets. Photograph by Richard Mortel, October 5, 2017. Image courtesy of Flickr.

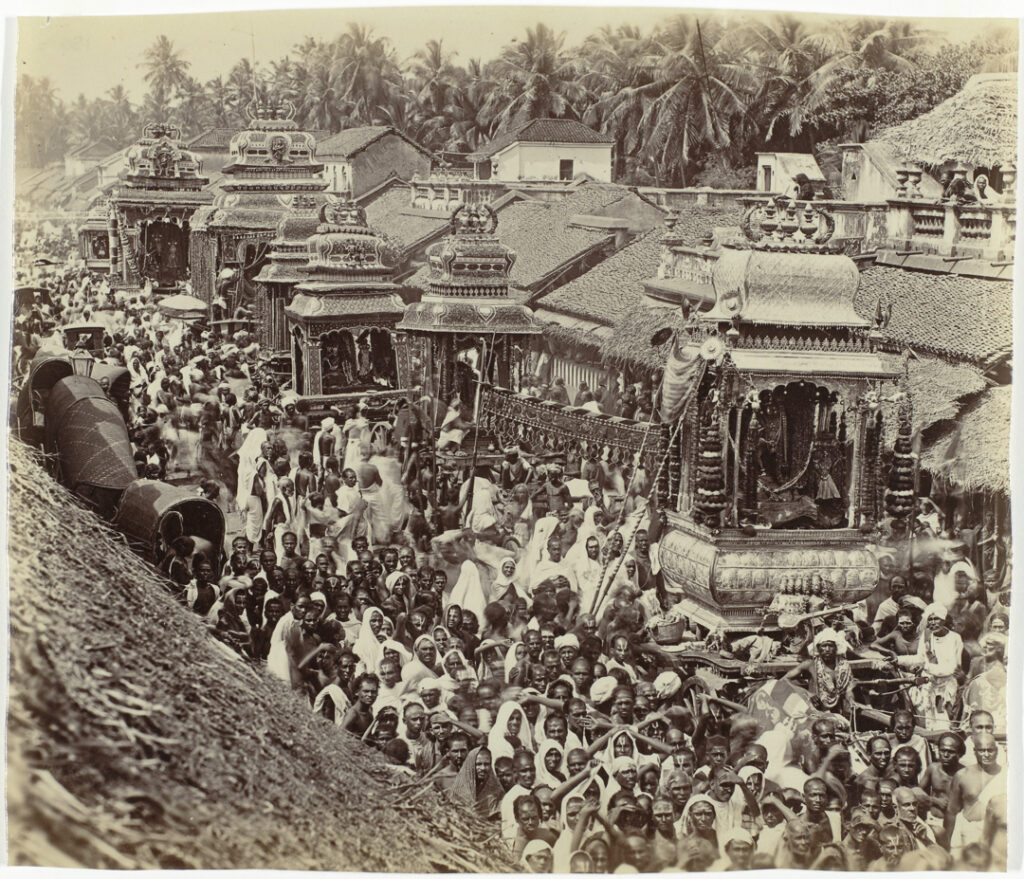

- Ratha Yatra procession with decorated chariots in Madurai, Tamil Nadu, India. The ritual and festive calendars of a temple brought together different artisans. Photograph by Samuel Bourne, Madurai, India, 1869 – 1870. Image courtesy of Rijksmuseum.

Weaver communities, who were historically also settled on the artisan streets surrounding temples, were one major artisan group linked to trade, and were therefore able to exercise solidarity for their benefit. In the Vijayanagara kingdom (fourteenth–sixteenth centuries CE) — a period scholars suggest was the high point for the weaving industry of southern India — textiles were a trade commodity critical to revenue and the upkeep of the kingdom’s military. In addition, the court and nobility were voracious consumers of cloth. Weavers themselves were also organised into guild-like structures and engaged with merchant guilds that facilitated the trade. The value of the commodity they produced allowed them a position for collective bargaining. Weavers in the Vijayanagara empire protested successfully against tax rises, sometimes using the tactic of migrating in large numbers to other regions to make their case. The Kammalar are known to have had a custom whereby all craftspersons of the community would shut shop if a member was offended or wronged. The economic position of these communities also provided them with social mobility and status, such as participation in temple events, caste insignias and the right to blow conch shells, a prominent ceremonial marker.

A bronze caster at work at Swamimalai, Tamil Nadu. Swamimalai remains an important centre for the living tradition of bronze idol-making using the lost-wax method. Photograph by Peter Chou Kee Liu, February 9, 2011. Image courtesy of Flickr.

One example of the community association with the Vishwakarma artisan group is found today in the pilgrimage town of Swamimalai in Tamil Nadu, where some bronze casters, who claim descent from medieval Vishwakarma artisans, continue to make bronze idols using the lost-wax method for ritual purposes and for sale in the commercial handicrafts market.

- Jahangir giving gifts to the Shaykhs. From the St. Petersburg Album, c. 1620. Objects of the court, from jewellery to garments, tents and carpets, as well as armour, would have been stocked and produced in karkhanas or workshops. Image courtesy of National Museum of Asian Art

- A court atelier; Folio from a manuscript of the Ethics of Nasir (Akhlaq-i Nasiri). Attributed to Sanju, Lahore, c.1590 – 1595. Imperially patronised ateliers attracted the best artists and craftspersons who created art and objects for the court. Image courtesy of Aga Khan Museum

- An object of luxury such as this one would likely have been crafted by master artisans at imperial or nobility-patronised workshops. Emerald set-box, Mughal India. c.1635. Image courtesy of the Khalili Collection.

In-house expertise: The Mughal imperial workshop

Where master artisans in southern India could simultaneously engage with court, temple and market, another form of artist organisation, the karkhana — literally, ‘factory’ — prevalent largely in northern India, crafted products exclusively for the use of the court or patron. The karkhana in this context was a place of craft production as well as a storage house for objects, patronised by a royal court or by a member of the nobility — a format that scholars suggest emerged in the Islamicate states of northern India with the migrations of artists, artisans and elites from Central and West Asia in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries.

The Mughal period, particularly from the late sixteenth to the early eighteenth century, was the apogee of this form of patronage, which was also adopted in the smaller provincial courts. In addition to the kitabkhana or book atelier referenced earlier, the Mughal court’s karkhanas or workshops also turned out furnishings and tents for the peripatetic court, alongside jewellery, opulent utilitarian objects, perfumes and weapons. At Amber, in present-day Rajasthan, in the 18th century, the karkhanas dealing with textiles alone included the rangkhana for dyeing, the chapkhana for printing and the siwankhana for embroidery. Because they served the court directly, the karkhanas were also organised in a bureaucratic structure, headed by an administrator under whom artisans worked. The court’s resources and the technical quality it demanded meant that these workshops attracted master artisans who specialised in certain areas of craft production, with craftspersons from other parts of the country also sometimes called on to work for the court. In addition to crafting objects, master artisans also helped train apprentices.

The Mughal imperial kitabkhana provides an example of how a royal atelier would have functioned. As an institution where manuscripts were not only stored but also produced and restored on royal commission, the workshop brought together artists and artisans specialising in domains such as paper preparation, binding, calligraphy, margin illumination, giltwork and miniature painting. Among painters too there were specialisations, such as flora and fauna, or portraits. When manuscripts were commissioned, each specialisation was called upon — with junior artisans working under the supervision of masters — to produce a work that achieved excellence and visual consistency. Even as the size of the workshop changed under different emperors with their varying artistic motivations, domain specialisation remained a feature of imperial workshops until their decline. Such karkhanas, both imperial as well as others, remained important craft-production organisations well into the eighteenth century, until the breakdown of Mughal rule and the emergence of British colonial rule pushed these structures towards their decline.

Collective legacies

The idea of a contemporary artist collective today encompasses self-driven management, an infrastructural and creative support network, and the lack of an explicit hierarchy, far-removed from the historical artist organisations that we have seen so far. Yet the spirit of collaboration and creativity, a sense of community and kinship based on common social experiences, work and familial ties, and support in the form of training and knowledge processes bridge artist and artisan organisations of the past and present.

About Rachna Shetty

Rachna Shetty is a Research Associate at the MAP Academy. She holds a bachelor’s in Mass Media from the University of Mumbai and a post-graduate diploma in Museology and Conservation from the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya (CSMVS), Mumbai. Her research interests include folk, performing arts, sports and popular culture. She is based in Mumbai. Email: rachna.shetty@map-india.org.

Rachna Shetty is a Research Associate at the MAP Academy. She holds a bachelor’s in Mass Media from the University of Mumbai and a post-graduate diploma in Museology and Conservation from the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya (CSMVS), Mumbai. Her research interests include folk, performing arts, sports and popular culture. She is based in Mumbai. Email: rachna.shetty@map-india.org.

About the MAP Academy

The MAP Academy is an open-access educational platform committed to building equitable resources for the study of South Asian art histories. It encourages knowledge-building and engagement with the region’s visual arts through its freely accessible Online courses, Encyclopedia of Art and Stories.

Bibliography

Agarwal, Simran. “Collaboration, Invention and Artistic Development: The Kitabkhanas of Mughal South Asia”. MAP Academy Blog. Accessed July 23, 2024. https://mapacademy.io/collaboration-invention-and-artistic-development-the-kitabkhanas-of-mughal-south-asia/

Archaeological Survey of India. “Sanchi through Inscriptions.” January 31, 2019. Accessed June 25, 2024. https://asibhopal.nic.in/pdf/recent_activity/200_years_of_discovery_of_sanchi_31_jan_2019/sanchi_through_inscriptions_dr_s_s_gupta.pdf

Balaswaminathan, Sowparnika. “Icons and Identities: The Work and Lives of Bronzecasters in Swamimalai.” Marg 67, no. 3 (March–June 2016): 10–23.

Beach, Milo Cleveland. Mughal and Rajput painting. The New Cambridge History of India, I:3. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

Britannica, The. Editors of Encyclopaedia. “guild.” Encyclopedia Britannica, March 2, 2024. Accessed June 20, 2024. https://www.britannica.com/topic/guild-trade-association.

Dehejia, Vidya. “Introduction: Sanchi and the Art of Buddhism.” Unseen Presence: The Buddha and Sanchi. Edited by Vidya Dehejia, xiv–xxxi. Bombay: Marg Publications, 1996.

Dehejia, Vidya. The Thief Who Stole My Heart: The Material Life of Sacred Bronzes from Chola India, 855–1280. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2021.

Gupta, Kanika. “Countering Cerebral Invasions: Sculptors Against Dependencies.” In Embodied Dependencies and Freedoms: Artistic Communities and Patronage in South Asia. Edited by Julia A. B. Hegewald, 347–64. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 2023.

Houghteling, Sylvia. The Art of the Cloth in Mughal India. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2022.

Kaligotla, Subhashini. Shiva’s Waterfront Temples: Architects and Their Audiences in Medieval India. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2022.

MAP Academy Encyclopedia of Art. “Mughal Miniature Painting”. Accessed July 23, 2024. https://mapacademy.io/article/mughal-miniature-painting/

Michell, George. The Hindu Temple: An Introduction to its Meanings and Forms. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1977.

Misra, R. N. Ancient Artists and Art Activity. Simla: Indian Institute of Advanced Study, 1975.

Mohsini, Mira. “Crafts, Artisans and the Nation State in India.” In A Companion to the Anthropology of India. Edited by Isabelle Clark-Decès, 186–201. Chichester: Blackwell Publishing, 2001.

Ramaswamy, Vijaya. “Sectional President’s Address: CRAFTS AND ARTISANS IN SOUTH INDIAN HISTORY.” Proceedings of the Indian History Congress 64 (2003): 300–336. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44145473.

Ramaswamy, Vijaya. “Vishwakarma Craftsmen in Early Medieval Peninsular India.” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 47, no. 4 (2004): 548–82. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25165073.

Roy, Tirthankar. “The Guild in Modern South Asia.” International Review of Social History 53 (2008): 95–120. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26405469.

Settar, S. “The Hoysala Artists (c. 1100–1336).” In Indian Art: Forms, Concerns and Development in Historical Perspective. Edited by B. N. Goswamy and Kavita Singh, 181–205. New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd., 2000.

Singh, Upinder. A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th century. Noida: Pearson, 2016.

Sinopoli, Carla M. “The Organization of Craft Production at Vijayanagara, South India.” American Anthropologist 90, no. 3 (1988): 580–97. http://www.jstor.org/stable/678225 .

Thapar, Romila. “The Social Role of Craftsmen and Artists in Early India.” In Making Things in South Asia: The Role of Artist and Craftsman. Edited by Michael W. Meister, 10–17. Philadelphia: Department of South Asia Regional Studies, University of Pennsylvania, 1988.

Thapar, Romila. A History of India: Volume 1. London: Penguin Books, 1966. Ebook.

Thaplyal, Kiran Kumar. “Guilds in Ancient India (Antiquity and Various Stages in the Development of Guilds up to AD 300).” In Life Thoughts and Culture in India. Edited by G. C. Pande, 995–1006. New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd, 2001.

Walker, Daniel. Flowers Underfoot: Indian Carpets of the Mughal Era. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1997.

gd2md-html: xyzzy Mon Aug 19 2024