Ancient Future by BIG juxtaposes Bhutanese traditional artisans with programmed robot milling arms. The danger is that we will overlook the value of handmade in our pursuit of efficiency and scale.

Two Bhutanese artisans, dressed in their traditional gho, a kimono-like garment, stand with hammer and chisel in hand, slowly and carefully carving patterns on a wooden beam. Their chisels slowly move along the lines of a drawn design, meticulously tapping away at grooves along the sinewy lines. What emerges is a series of three dragons. One clutches jewels that represent the beauty of Bhutan’s nature and its monarchs. The second holds a Dharma Wheel, reflecting the Buddhist nation’s present transformation. And the last bears the Double Vajra, symbolising future harmony. These reflect the traditional

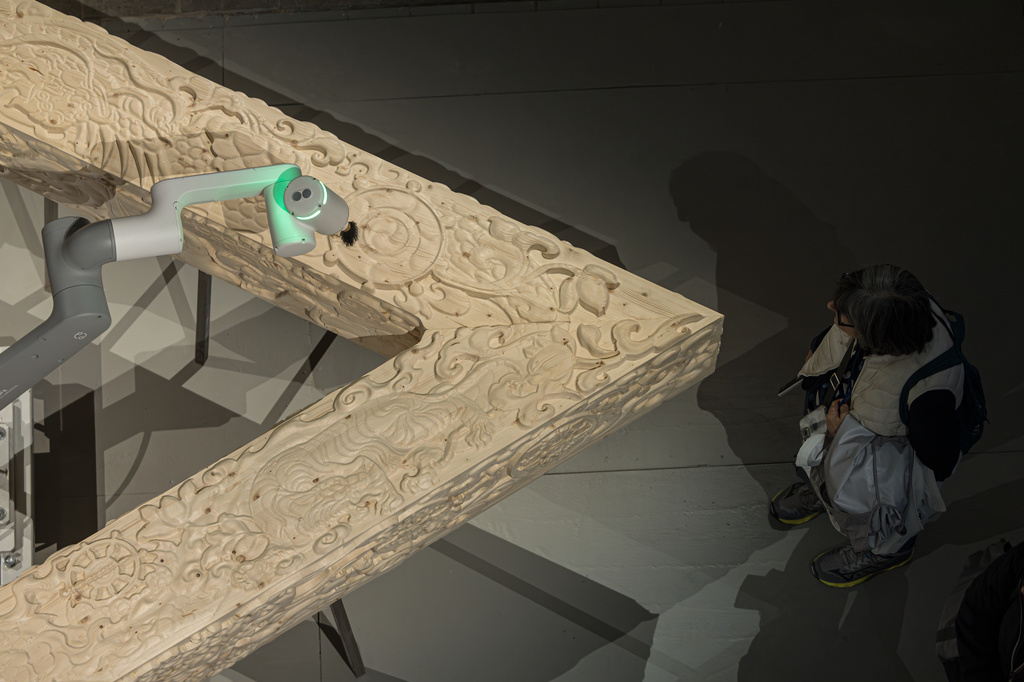

They are not alone. While the Bhutanese carvers are at work, two whirring robot milling arms follow identical patterns on two additional beams, brushing away the sawdust from the grooves they have precisely carved based on CAD drawings loaded into their software.

This meeting of carvers and robots is part of an installation at the 2025 Venice Biennale Architettura, reflecting the theme Intelligens. Natural. Artificial. Collective. The Ancient Future project is produced by the Danish architecture company, Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG).

While it might seem to be replacing human skill, BIG partner Giulia Frittoli claims that the project is actually enhancing our craft capacity:

‘Machine intelligence allows craft to be scaled, but the artistry and ideas remain rooted in human hands… This is the synergy we are exploring: by working with machines, we can make architecture more human. Rather than separating heritage and modernity, Ancient Future looks at how the two can grow side by side.’

Most responses to Ancient Future reflect this celebration of the partnership between humans and machines. But there are critics. Stefan Novakovic for AZURE magazine has criticised the installation’s colonial overtones, as demonstrated by the decision to omit naming the Bhutanese carvers. He concludes that “the region’s material culture is foremost a commodity to be mined”. While there is substance to this critique, it is worthwhile delving more deeply into the thinking behind this project to understand what it reveals about the future of craft in an age of robotics.

The beams are being carved as prototypes for a new airport, which is part of Bhutan’s ambitious Gelephu Mindfulness City project. The Bhutanese Buddhist ideology fits well with the philosophy of the company’s charismatic founder, Bjarke Ingels. His concept of “hedonistic sustainability” seeks to counter the more Puritanical approach to environmentalism, which emphasises self-denial. You can be both eco-friendly and visually pleasing. The positivist mentality of having your cake and eating it too is demonstrated in the $1.5 billion New York landscape project, BIG U, which combines storm damage prevention in the wake of Hurricane Sandy with a welcoming natural environment for residents.

The specific idea most vividly evoked by Ancient Future is the “bigamy of opposites”. Ingels seeks to bypass binaries to celebrate a free play of seemingly opposed forces—in this case, man and machine. This contradicts the narrative of machine displacing humans, which has guided the resistance of craft to modernity. By contrast, the concept of a robot partner aims to assist artisans by enabling them to scale up their production.

Architecture professor Malcolm McCullough prophesied the premise of Ancient Future in his visionary book from 1998, Abstracting Craft: The Practiced Digital Hand. In his book, McCullough presented the distinction between “autographic” practices, such as painting, which are unique, and “allographic” forms, such as music, that can be coded into sheet notation. McCullough argued that the process of abstraction involved in moving towards the allographic was a positive evolution for craft. Thus, new technologies will inevitably enable the manual process of craft to be coded into software used on machines such as robot milling arms.

This need not involve replacing the craft master. The idea of a “robot assistant” has been presented positively in Garland previously in the article about the Chinese embroiderer who used a machine apprentice. The robot here can perform the drudgery that a master will usually leave to others, who are becoming increasingly difficult to find.

But Ancient Future is a step beyond the humble “assistant”. In the Bhutanese project, once programmed, the robot can completely replace the artisan. We find ourselves in a familiar yet tragic scene today, where workers are programming the AI that will replace them, such as call centre staff for banks who are training chatbots that will render them redundant. While this provides some work initially, it is only short-term.

The concept often used to critique this situation is “vanishing mediator”, as articulated by Slavoj Zizek in For They Know Not What They Do: Enjoyment as a Political Factor. In this set-up, what is proposed as a means of saving an entity ultimately leads to its demise. A key example is Protestantism, which initially emerged as a means of reviving spirituality but ultimately led to the emptiness of modern capitalism. It’s like the joke, “We won’t have cannibals any more. We ate the last one yesterday.”

The world of happy opposites is a reassuring fantasy, where lambs lie down with lions. Facebook is filled with images of inter-species love. While heartwarming, the danger is that it lulls us into a false sense of security. Though we might enjoy the scene of colourful Bhutanese artisans working alongside their robot partners, there is no reason why the artisans will remain when it is so much more efficient and cheaper to have the carving done exclusively by machine.

In 2008, I visited a silk factory in Hangzhou. The showroom presented an idyllic scene of artisan embroiderers studiously at work with their needles, dressed in traditional costumes and accompanied by soothing Chinese sounds of the guzheng zither. But this was mere theatre. When I wandered around the corner to the actual factory, I found a cacophonous scene with massive mechanical looms pumping out silk fabrics. A couple of harried workers scrambled around to grab the old loose thread. Craft was a mere facade.

In an increasingly simulated world, we need to attend to the unique quality of the handmade. This involves close attention to process. It’s hard to tell from the photos the difference between beams carved by machine or by hand. You need to see them in real life. But the robot-made designs will likely look relatively sterile, too perfect.

This need not be a purely visual phenomenon. The mere knowledge that a work is handmade can change our perception of it. When blind-testing diners about their after-dinner coffee, a study found that the Nescafé pod version tasted better; however, when informed about its production method, the handmade version was preferred. Handmade feels good.

How does this work? A unique quality of being human is our innate capacity to empathise with others. Recent research has even identified a biological basis for this in “mirror neurons” that enable us to feel pain when we see an injury in others. The value of “made with love” in handmade products reflects the vicarious pleasure we can derive from products made by people who genuinely enjoy their craft.

Thus, the knowledge that something was made with human care can alter the way we perceive an object. However, like all cognitive pathways, mirror neurons can decline with disuse. We need to exercise them. In a way, the stories shared in Garland provide a way of doing that. Each story follows the journey of a maker as they produce work with care and patience.

It’s the story behind what we make.