A chance discovery in his garden leads Peter Cummings on a quest for the perfect glass engraving tool.

I was living in a tiny miners’ cottage with a big garden, in a small town north of Bendigo when I found myself at a crossroad. It was the 1980s. I was in my early thirties and burnt out from a social welfare career that had been my identity and meaning in life. Digging in the garden for exercise and to fill in time I found a small old glass jewellery piece. Impressed on the back was a flower design. Originally it would have been painted, but I liked the clarity. Fascinated by the decoration more than the made object, I headed to the library—many libraries as this was pre-internet. The more difficult the challenge, the more the obsession.

I found books, old even then, detailing “Point engraving” using a diamond or tungsten stylus to tap dots in a stipple manner—also fine lines for pictures or names and designs. There was not enough grunt, although I still use this method occasionally. I then found a book teaching drill engraving with diamond plated burrs. Deeper carving, intaglio style, captured the light refraction that I was looking for. I progressed through stronger drills such as a Dremel and my favourite, Foredom. I also slowly moved from tracing designs to photos and drawing my own designs. The bookshelf grew and the internet exploded my horizons. A couple of TAFE Diplomas fed my thirst for art education. In the background, there were always two issues just out of reach as an Australian isolated from a glass engraving world: the traditional copper wheel engraving lathe, and meaning beyond mere decoration.

Engraved glass has been around for thousands of years. It is closely aligned with lapidary work. As luxury materials decorated and celebrated for emotional meaning, engraving glass and gem-cutting share a lot of methods and equipment history. Roman engraved gemstones and Chinese jade carving from around the first century AD exist alongside exquisite Roman and Middle Eastern glass engraving. Not a lot is known about the methods and equipment but similar later works lead to an understanding and respect.

The early seventeenth century saw developments in glass production that encouraged gem carvers to use their skills and equipment in the service of European royal courts. A new craft industry was established. Examples from that period of intaglio carving on clear glass can be seen in the National Gallery of Victoria. The gem cutter’s lathe had a few changes in power and cutting grit, but the basics are the same today. Larger machinery was developed for the “cut glass” industry that used larger wheels for cutting and brilliant polishing.

Around 2012 I found my Melbourne job gone from under my feet and, in my 60s, not likely to get another. A small mortgage wasn’t going away. So a pack-up and move to Sale in Gippsland allowed me to set up a comfortable studio space. Starting TAFE art studies opened my eyes to the wider art world although glass was not accepted as a study subject. Determined to push on I bought the German portable Merker K MK1 portable engraving lathe. The Australian dollar was at its peak but, with a set of diamond wheels, it still cost nearly as much as a small car. I drove to the Tullamarine freight import depot in a trance.

It is fully self-contained and portable, which is handy for demos. The motor, bottom left, runs pulleys for speed control up to the shaft above. Stopping to change speeds is something I don’t mind. It allows me to reset my concentration as working on a small area sometimes ruins perspective. Water from a small bucket above drips through a tap. A leather strap spreads it over the wheel. A drip tray is underneath, elbow pads, and the quirky rubber tyre wrist straps stop the water running down my arms.

The carving is done by the interchangeable wheels on spindles from the rack. Size and profile determine the shape and size of the cut they make. Grandma’s cut crystal has geometric patterns made from bigger wheels placed on and off, or moved along lines. Engraving is based on moving the glass and wheels around into a modelling form of sculpture. Different wheel profiles carve different angles within that form. This close-up working picture is dry because I have turned the water off to get a clear picture. Using a medium-sized flat wheel at an angle, I am scooping out a large rounded form of a gum leaf. The narrow cut down the centre that will become the stalk is cut with a sharp mitre profile wheel. Right above my hand is a leaf semi-polished with a stone wheel.

Diamond wheels generally keep their profile, but traditional copper and stone wheels continually needed reshaping. Copper wheels work by applying a grit/oil mix. The benefit of copper and stone is that you can make your own wheels or change them to suit without laying out hundreds of dollars for a new diamond wheel. These wheels are below the cut they make. Stone wheels on the right I have started making myself. Made from bench grinder aluminium oxide wheels, they have different profiles and grits of 120, 220 and 400. Polishing can be done with a cork wheel and pumice paste which is messy but really cool to see.

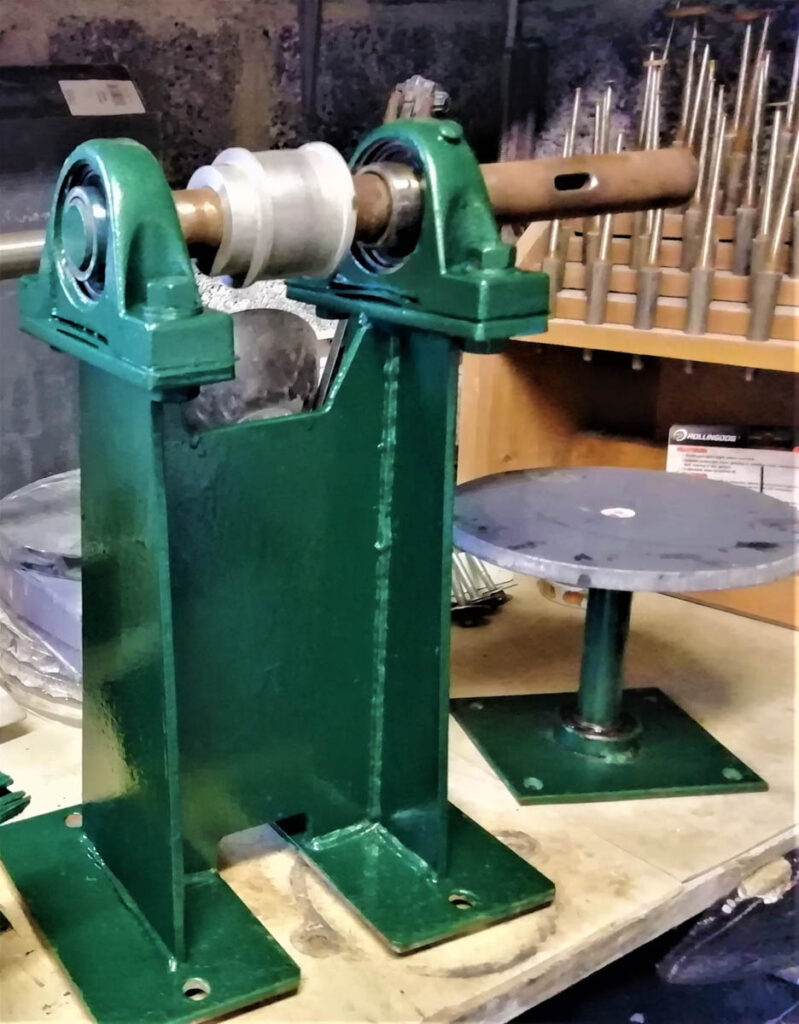

Traditionally glass factories made their own lathes and all the equipment their businesses needed. Good used equipment is now hard to find and new specially made lathes are very expensive. Master engraver Greg Sullivan and Waterford engineers made an affordable entry-level lathe that is robust enough for fitting copper and stone wheels with the shaft machined to take ready-made diamond wheel spindles.

Covid lockdowns made it impossible to get it to Australia at the time, So with specifications, I approached local engineers to make one. It seemed well within the scope of a professional workshop. Serious illness, machine breakdowns and lack of imported parts, as well as a lack of trained staff, mean I am still waiting. I have made some stone wheels and will make copper wheels soon for their silky smooth finish. There is only a small pulley because my new lathe will have a variable speed motor. My aim is to help anyone interested to have the opportunity of an affordable machine. All the knowledge I have and enthusiasm will be a pleasure to pass on.

- Peter Cummings, Slave After Michelangelo,2012, fused Engraved Glass,45x45x10cm, photo Peter Cummings

- Peter Cummings, Mongol Riders Of Bmx Clan,2018 28X16x16, Graal Blown By Philip Stokes,28x16x16, Photo Peter Cummings

- Peter Cummings, White Hot Orchid,2012, Fused Drill Engraved Glass, 16X46x3 Cm Photo Peter Cummings,

- Peter Cummings Matriarch. 2021 Commercial. Diamond Wheel E

Intaglio engraving is carving in three dimensions, but in reverse, as in carving a mould. In fact, to check details I use a plasticine impression or plaster cast, which can be kept as a record. Viewing from the side opposite the work gives you a realistic look of relief coming towards you. This is where the clarity of glass excels. When I use vessels to view multiple panels at once it is a challenge with benefits few other art forms can match. Coloured layers, sometimes with clear, allow expressive pieces limited only by imagination.

Collaborating with glass blowers, fusing and architectural specialists has opened a field similar to Europe where long traditions have not limited innovation. I am also fascinated by the traditional subjects and motives or concepts of engraved glass. From my first efforts at putting names on glasses and special commemorative pieces, I have seen the intense emotion this can generate. Similar to bespoke jewellery or furniture a part of our life is enriched. There is a long tradition and no reason we cannot continue along that line with similar subjects such as memorials, commemorations, politics, religious and social issues.

I have taught myself glass engraving through books, lately the internet and largely lots of experiments and practice. Flashed bowls, cased cameos vessels, graal, fused layers, but clear intaglio is still the most captivating. This year I’ll have pieces in a GlaasInc exhibition at Prahran. Hopefully, there’ll be enough interest to follow up with a workshop and demonstration. Watching someone engrave with a lathe is a rare experience, particularly when we handle glass every day without thinking of it being decorated. It is slow and deliberate with a soft hum and a smooth sanding sound. Every touch and nuance is there to see.

Further Information

Techniques of Glass Engraving. Jonothan Matcham and Peter Dreisser.

Kaminecky Senov has the oldest glass school with engraving as a specialty.

Melbourne-based centre for glass education, with the main focus on leadlight and glazing

About Peter Cummings

Peter Cummings has been a practising glass engraver for over 30 years. Outside the academic establishment, he has studied the traditions and explored many facets of this ancient art form. Books and now the immense resource of the internet feed his imagination and negate isolation. Overseas experts provide encouragement as well as technical expertise from their many years of experience. Material and equipment issues remain a concern for Peter. He is driven to provide information and expertise for other artists to include in their own diverse practice. He is also keen to pursue the conceptual ideas that imbue emotional value which are part of the history of glass engraving. Political, commemorative and deeply personal, there is a serious need for this craft today.

Peter Cummings has been a practising glass engraver for over 30 years. Outside the academic establishment, he has studied the traditions and explored many facets of this ancient art form. Books and now the immense resource of the internet feed his imagination and negate isolation. Overseas experts provide encouragement as well as technical expertise from their many years of experience. Material and equipment issues remain a concern for Peter. He is driven to provide information and expertise for other artists to include in their own diverse practice. He is also keen to pursue the conceptual ideas that imbue emotional value which are part of the history of glass engraving. Political, commemorative and deeply personal, there is a serious need for this craft today.

Comments

What a fantastic article about a fantastic man. Peter is so devoted to achieving goals and then passing on his knowledge. You can feel his passion through his words.

Congrats Peter, Excellent work and editorial regarding your work.

How do you contact Peter, I’m in the UK, Paula

Hi Peter …I just love your very informative story…why don’t you live in Sydney !!! I have recently begun etching glass and love it even tho I am experimenting at this point …there is so much to know…it’s a wonderful medium !