Ros Bandt recounts the history of her aeolian harp, which has voiced the wind across the land.

The presence of the wind in Australia is a fundamental element shaping the land and its peoples. The wind has carved the landscape for thousands of years, actively changing its geomorphic composition on a daily basis. It erodes, moves layers of red dust through the Mallee, fans and directs the frequent bushfires, and controls the surf. It stirs the spindly casuarina, Australia’s native pines, until they make wonderful tones of the harmonic series in just intonation, earning them their affectionate name, the whispering pines.

Native grasses and swamp rushes rustle, as do the leaves of the poplar. Holes and crevices in the land itself can emit sound when the wind is from the right direction and strength. The energy of the wind has been used to drive windmills for water, and more recently, for the generation of electricity in the new wind propeller farms in Albany, and Portland. Sound is often an undesirable byproduct of such activity. So too the wind sonically activates manmade structures, albeit unintentionally. Telegraph wires and fences sing.

The word “aeolian” is derived from Aeolus, the ancient Greek god of the winds. Hence its meaning, “of, produced by or borne on the wind; aerial, as in Aeolian harp, a stringed instrument producing musical sounds under a current of air.” (The Shorter Oxford English Dictionary p.29). The greater number of aeolian art practices are aeolian harps or wind harps, involving the activation of strings where the aeolian principle comes into play. Without the physical components of the wind being in the right relationship to the vibrating object, the work will not sound, (speed, direction, pressure).

My Aeolian harps were first constructed in Redcliffs, near Mildura for the last Mildura Sculpture Triennial, held in 1988 on the banks of the Murray River. I invited the listener to engage in the intimate act of listening by turning away from the traffic and placing the ear to the mast.

Sensual contact is made with the elements; aerial sounds float to the ear, the strings can be touched and the transferred vibrations can be felt as well as heard, throbbing in the wooden masts. The wind is in a state of theatrical play, the listener hears the wind as a jester.

Cobwebs in the moonlight

I was invited to go to Mildura as an artist-in-residence for the Sunraysia Craft Council to do a sculpture. At the time, I was very much interested in electronics and transducers and I thought I would make a big steel plate with the transducer and feed the sounds of the space and the adjoining vineyard through that. The head of art at Mildura High School wanted me to work with the first sound sculpture group of VCE students in Australia. So I was mentoring them with woodworker Stephen Naylor. His wife Marjorie was head of the Crafts Council so they invited me to stay at their place out in Red Cliff and dream something up.

When I arrived it was so hot that if I had proceeded with my plan, I would have set the whole place alight. So I just stayed out all night and played my recorder under the torulosa casuarina trees and quandongs up there. Near midnight, I saw this enormous spider’s web illuminated in the moonlight. And it just came to me. I just stood it up vertically in my mind and I just took out every second part of this cobweb. This left four harps standing in a vertical position and the centre point went up to the sky to the moon

It was a team effort to build the design I had sketched. We had to use a router and some terrific tools. We turned the keys all together. First of all, we turned wooden ones and then they didn’t really stand the test of time before we took the whole sculpture to Lake Mungo. Three years later, we made metal ones that would be more stable in the really hot climate.

The harp stayed at that high school with Steve Naylor, who was head of sculpture and digital arts for years. Everyone in the school learned how to be a keeper of that harp. So they had to go and tune it. It wasn’t just about doing something, but caring for this object, so they learned how to do that. They had to listen and be in tune.

It was installed in the back of a school. One pair of scissors and the whole thing would be over. There were only two broken strings in the top that a cockatoo had flown into in that whole three years. It is a really good story for the education system in Victoria. It was a beautiful way that those children came on board and cared for the sound of their place. It was like in Ireland where every house would have a harp on the door and when you sell a house you don’t take the harp away. It belongs to that place.

Lake Mungo

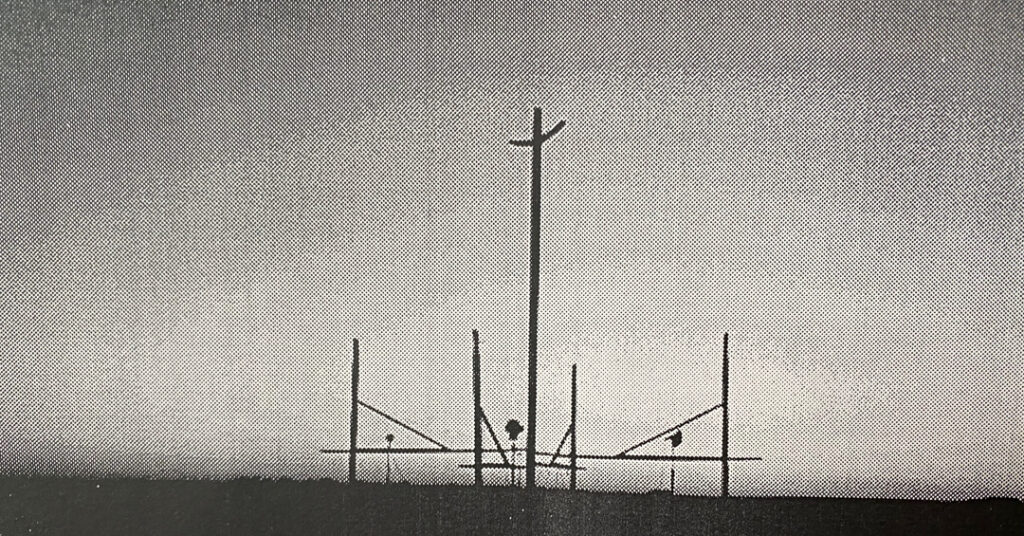

Edric Slater CSIRO, Andrew McLennan ABC, Ros Bandt aeolian harps sound sculptor and composer, Steve Naylor woodworker, Lunette, Lake Mungo; photo: Arthur McDevitt

These Aeolian harps were recommissioned to be recorded by the ABC at Lake Mungo, in New South Wales for the Sound Art Australia Prize organised by the ABC, and the WDR. The presence of the wind is everywhere in this remote desert environment. It has eroded fossil-like forms, carved into human-sized shapes standing erect like spectres, and the layers of the ancient earth are revealed beneath the feet in a map of geomorphic history, complete with pre-ice-age fossil fish and shell middens, signs of the first human habitation. Each day the wind cleanses the marks of daily activity on the high sand dunes of the lunette surrounding this ancient dried salt lake. It is a wind-driven soundscape.

As the Mutti Mutti elder, Alice Kelly said, the harps seemed to be reaching right back to the Dreamtime, drawing us all together in what has been and what is (McLennan, 2002). The great beauty of the just intonation was making this relationship for her as she had often heard very similar sounds in the casuarinas as a child. The harps became integrated with the natural environment. When the weeklong recording session was over, the harps and all of us returned to our origins without leaving a trace.

The harps may be played by many people at once. Each harp is of human height for ease of playing. There are 14 aerial strings in the overhead centrepiece and four bass rider strings which connect from the upper strings to each of the four surrounding harps. This means more bass tones can be plucked. The sound skates through the harp’s entire oregon structure radiating through the central pole, a wonderful place to listen to the spatial sound, played by wind or human.

Upon the advice of Aunty Alice Kelly, I have continued to use aeolian sounds I make and record in many sound installations, composed and performed sounding artworks, in many locations around the world. The sound of the wind unites us all she said, brings us together. To this end I have maintained the aeolian harps sculpture since the late eighties, refurbishing it and restringing it when needed. I have created many over the last thirty years, commissioned by young harpists, Isla Biffen Outback for prepared harp, Windharps commissioned by Mary Doumany for the international harp conference in works and recorded by the ABC and available on the podcast

Acoustic Sanctuary

My Aeolian harps are currently located in an “acoustic sanctuary” in Central Victoria. An acoustic sanctuary is a place to contemplate our sonic habitat and the sounds we inscribe as significant. Sounds have meaning whether wanted or unwanted. In a sound garden, one can consciously include wanted sounds such as aeolian harp wind sounds. But we can also contemplate sonic weeds, sounds we want to eradicate so that the sounds that are endangered and the sounds we want to preserve can be more audible.

What is our sonic heritage? What do we understand about Australia as a sung country and do our sounds collect in the collective consciousness of the Dreamtime? We are sharing inscribed acoustic habitats, wittingly or unwittingly.

Listening is another way of being, which inscribes and endorses silence. Not to listen in a land, which has been sung for thousands of years by many peoples, is to deny their existence, ever widening the gap of silence and endorsing the colonial imposition of terra nullius. The practice of listening has changed as the culture has changed.

The decision to acquire the 55-acre property in Central Victoria was a sonic love affair from the start. On the first visit, I sonically identified five species of frogs. This meant it was well on the way to being regenerated. The sounds echoed all around the valley. I was seduced. This love affair with the sounds of the natural environment never errs. By making it land for wildlife we wanted to continue regenerating it and be able to maintain this off-grid substantial wildlife corridor from the town to the national forest. From the outset it was to be a quiet place, no introduced sounds, fast cars or motorbikes, no smoking, take your rubbish with you.

The shape of the land as acoustic space is awesome. The five sets of natural north-facing rises to the south boundary form an amphitheatre array down to a small intermittent stream tributary. Water had been introduced in two large artificial dams and smaller ponds. The dams have grown sedges and frog communities expanded. A little plains brown tree frog was conceived in the kayak at the edge of the dam in 2016, and it is his home. His signature call can be heard most of the year, 3-5-7 slowly repeated grating notes creeeee-creee-cree- cree.

Over the 25 years, all the motor-bike and jeep tracks of the former owner have become overgrown, changing constantly according to the seasonal needs of the kangaroo population which has always been vast. They are making their tracks over mullock heaps, also becoming overgrown with the Cassinia bush, so important for understory regeneration nitrating the soil.

There are only kangaroo tracks now and no fences apart from the high south boundary where goats and cows have been introduced as a small venture by the neighbour. Moos and bleats are sometimes heard from this denuded place floating down the hill through the bushed amphitheatre.

It was after some years of being in place with all our senses off-grid living slowly in the rhythm of the land that we realised what we were in, an acoustic sanctuary, a place to celebrate the sounds of an endangered habitat. When local Murray man Ron Murray gave me some ochre left over from a children’s workshop for the writer’s festival for children, I went home and painted the words above the shed: “Acoustic Sanctuary”.

The Acoustic Sanctuary at Fryerstown has evolved slowly over more than three decades. The biodiversity is continually being documented since becoming Land for Wildlife in 1996. Several generations of owlet nightjars maintain sovereignty in the shed unless the powerful owl returns to the tree by the back door. Grey shrike thrushes breed each spring in the eaves and a pair of olive-backed orioles inhabit the south side.

The crimson rosellas colonise the bridge over the streamlets in the stands of mature grey and lemon box. They share the upper storey with corellas, sulphur-crested cockatoos, choughs, magpies, and currawongs. While the superb fairy-wrens, robins and weebills dart into the scrub near the ground, by the waterholes herons, egrets, cormorants, native ducks, lapwings, wait their turn.

On the side of the track, bronzewing and crested pigeons guard the entrance to the place while further along, pallid cuckoos, bush wrens, thornbills, weebills, fantails, willie wagtails are stable nearby residents. Jacky winter and scarlet robins are widespread breeding residents. This ensures a myriad of aerial sound compositions as they go about their business in temporal layers of intricate complexity, a sonic composition. Box ironbark-dependent fauna includes many endangered species of birds, woodland brown and white-throated tree creepers, mistletoebird, regent honey eater, coming at the flowering times for the sugar food of lerp and pollen. Other elusive presences are the rufous honeyeater, swift parrot, and small marsupials, phascogale, antechinus, tree goannas, skinks and stumpy-tailed lizards. Microbats and native bees, termites, underwater yabbies and aquatic invertebrates, small crustaceans and insects are being further investigated both scientifically and artistically. My hydrophone in mud or from the kayak is a constant sonic treat. The tiny orchid season, Bom, meaning ‘orchid’ is particular to this area being the 7th aboriginal season, named Guling here.

Questions

A printed leaflet is available, but I tend to keep it as a leaving present, something they can think about again later as to what the experience might have meant. The questions it asks are below as a means of provoking modalities of listening and reflections through sound.

SITE LISTENING: ENGAGING WITH SOUND.

BE STILL. QUIET.

CONSIDER WHAT IT MEANS TO SHARE THE SOUNDSCAPE. Be aware of the sounds you are making.

WHERE ARE YOU IN THE COSMOS?

Listen for a while, all around, standing, up down, in front behind, lying down, locate moving sounds, distant sounds, tiny sounds. Listen to the breeze in the scrub, the trees, the harps. Listen inside to the harmonic series, the particles which move and shape sound.

Listen to the sound underfoot, how dry is it?

Listen and locate other moving sounds.

What is happening in the upper canopy, or behind you? Listen to sounds recorded in water through the hydrophone, on the CD JaaraJaara Seasons.

Listen to sounds at night.

Compare them with diurnal sounds.

How do sounds change with the seasons?

Which sounds are familiar/unfamiliar

Which sounds are special to this area?

Listen for a long time… over the course of the year

Visit and listen to the 12-month sonic calendar at www.hearingjaarajaara2013.wordpress.com

Credit: Taming the Wind: Aeolian Sound Practices in Australasia, The Acoustic Sanctuary: A Dedicated Listening Place.

About Ros Bandt

Dr Ros Bandt is an award-winning sound artist, composer, environmental sound installation artist, instrument builder and multi-instrumentalist. She received the arts faculty award for excellence in Research at the Australia Centre, the University of Melbourne. On her 3rd ARC grant she became the Founding Director of the Australian Sound Design Project, the first online database and online gallery of Sound Designs in Public Space in Australia. She has pioneered sound sculpture, sound playgrounds, spatial music, spatial interactive installations, written the definitive book on her first ARC grant, and installed whole buildings in sound and light (Grainger Museum Melbourne International Festival). She was winner of the Sound Art Australia prize, the first woman to win the Don Banks Award for their life’s contribution to Australian Music and received the Fanny Cochrane Smith sound heritage award from the National Film and Sound Archive. In 2020 she won the Richard Gill Award for her distinguished services to Australian Music, changing and challenging what music and sound might be. She has been invited to sound ancient Sites around the Mediterranean including Ggantija, Dodoni, Delphi, Hydra and Prespes. Her books and writings on sound can be accessed from her website as can her original creations and publications on Bandcamp. Visit www.rosbandt.com. Photo: Arthur McDevitt

Dr Ros Bandt is an award-winning sound artist, composer, environmental sound installation artist, instrument builder and multi-instrumentalist. She received the arts faculty award for excellence in Research at the Australia Centre, the University of Melbourne. On her 3rd ARC grant she became the Founding Director of the Australian Sound Design Project, the first online database and online gallery of Sound Designs in Public Space in Australia. She has pioneered sound sculpture, sound playgrounds, spatial music, spatial interactive installations, written the definitive book on her first ARC grant, and installed whole buildings in sound and light (Grainger Museum Melbourne International Festival). She was winner of the Sound Art Australia prize, the first woman to win the Don Banks Award for their life’s contribution to Australian Music and received the Fanny Cochrane Smith sound heritage award from the National Film and Sound Archive. In 2020 she won the Richard Gill Award for her distinguished services to Australian Music, changing and challenging what music and sound might be. She has been invited to sound ancient Sites around the Mediterranean including Ggantija, Dodoni, Delphi, Hydra and Prespes. Her books and writings on sound can be accessed from her website as can her original creations and publications on Bandcamp. Visit www.rosbandt.com. Photo: Arthur McDevitt

✿

This article was drawn from Ros Bandt, Taming the Wind: Aeolian Sound Practices in Australasia, Organised Sound, 2004, 8(2), 195-204; Ros Bandt, The Acoustic Sanctuary: A Dedicated Listening Place, Soundscape, The Journal of Acoustic Ecology, 2019, volume 6 number 2 | fall /winter; and interview with Kevin Murray, 10 May 2023.