Gary Warner re-traces a life in sound in which he produces experimental works that realise the sonic potential of the world around us.

In 2020 I launched my sound art and field recording podcast series Sonic Sketchbooks. As a teenager, I was enthralled with making, recording and manipulating sounds of the world and sounds made with everyday things. This was in the 1970s when affordable portable audio cassette recorders were relatively new.

Since those distant electromagnetic, electromechanical times, I’ve continued to work with and explore sound—as a player in punk bands, making soundtracks for my and artist colleagues’ films and videos, making and commissioning soundscapes for museum and gallery exhibitions, and, as an independent artist, conceiving performative events and making sonic objects and installations. Here are stories of a few projects.

a cryptic lamellaphone, 2014, timber, brass, steel, pingpong balls, ink, acrylic paint, 650mm diameter x 50mm (h); object support & seating

This object was created as part of an installation titled “Songs for Robert Brown” and is an inversion of my social lamellaphone, a large circular musical instrument that five or more people can play at once. This alternative instrument is cryptic because the mechanism of its sound production is hidden inside, and though it produces melodious sounds from the same materials as the social lamellaphone, it cannot be played in any conventional sense. It is an instrument for the sonification of randomness and performance of musical uncertainty.

A featureless broad, flattened wooden cylinder rests on a low stool. A pair of identical stools face each other across the object. People are invited to sit in pairs to hold and move the object in their hands. Their actions generate sounds of rolling, bumping, and random sequences of resonant metallic tones within the object. A curious tension arises between the performative pair as they negotiate how to make sounds together. Each can feel the other’s movements. Still, neither can be sure how any action relates to a particular sound. It seems (and is) impossible to repeat a melodic sequence.

The object’s unadorned exterior and sense of a mechanism hidden within prompt investigation by peering into slots around its perimeter. Like looking into a microscope, there is an odd sense of scale transition upon seeing the shadowy world within. Now we can see what’s going on and guess what’s happening to generate the sounds.

Inside are thirty-four small hardwood bridges, each clamping a thin steel strip. These strips, of different lengths, are cut from street-sweeper bristles I collected from Sydney streets. They break from large circular brushes underneath the vehicular cleaning machines. Different lengths produce different tones; shorter are higher, and longer are lower. These strips, or tines, are carefully arranged so three ping pong balls can roll about and knock against them to create random musical sequences that people say remind them of childhood toys and pinball machines. It took a lot of experimentation to locate the tines, so the ping pong balls strike them “just so” to create rich resonant notes. The hardwood discs that sandwich the bridges, the cylinder’s skin, serve to amplify the vibrations which can also be felt in the bodies holding the object.

The object’s form is redolent of the zoetrope, a nineteenth-century optical device. But rather than the animation of vision, this object animates sound, relationship, association and memory.

Robert Brown (1773-1858) was a Scottish natural philosopher who accompanied Matthew Flinders’ 1801-03 circumnavigation of the Australian continent, collecting and describing thousands of botanical species. He also compiled word lists from meetings with Aboriginal people in what are today Arnhem Land, Perth and Sydney. Some of these lists were only discovered in the NSW State Library archives in 2013.

Back in England, in 1827, Brown observed through his microscope a curious phenomenon that he carefully described in a scientific paper but could not explain – the random motion of minute particles in suspension in water. How could inanimate material, such as pollen grains or dust, move about as if alive? In the early twentieth century, Australian physicist William Sutherland, Polish scientist Marian Smoluchowski and Albert Einstein independently theorised what Brown had seen. They saw it as evidence of molecular activity. This work was central to the development of quantum physics, stochastics and the analysis of complex systems. The phenomenon is now known as Brownian motion, and my cryptic lamellaphone is a homage to it and Robert Brown’s curiosity.

21-pendulum entropophone

Gary Warner, 21-pendulum entropophone 2015, aluminium cans, dowel, concrete, beads, string, dimensions variable

Visitors are invited to push the pendulums gently to activate the instrument.

This instruction was posted on a wall near my 21-pendulum entropophone (sound of entropy), a suspended kinetic-acoustic array installed at Articulate project space, a Sydney artist-run initiative. The instrument redeploys over 150 discarded aluminium drink cans collected from the street. I cut off their tops with a Dremel and used a roofing nail to punch a hole in each tin’s base to attach a string.

Activated by visitors, the entropophone produces atonal clattering cascades, rhythmic pulses and melodic sequences that gradually decay to the silence of equilibrium as the energy provided by a visitor’s action is dissipated. Heard from nearby, the sounds are reminiscent of distant moored boats, wandering farm animals, a forest gamelan or temple bells. If the listener brings their ears close to the hanging cylinders, the sound is suddenly experienced as surprisingly rich, resonant and complex.

The installation comprises seven roughly identical linear assemblies hanging in parallel. Each is made up of a 2.4m dowel hanging from the ceiling and suspending 20 to 25 of the open-ended tins, cut to slightly different lengths. Each dowel is weighted at either end by a pendulum bob made by filling a 250ml can with concrete. These two bobs hang close to the ground on long lines. Another bob hangs in the middle of each dowel; its string is relatively short. The tins hang on shorter threads near the centre pendulum and get longer toward the edge pendulums, creating a triangular colonnade for visitors to walk through. The tins are slightly separated to knock against each other when the dowels are agitated by movement of the pendulums. Many tins have a wooden bead dangling inside to add another sounding element to the mix. The seven dowels are set about one metre apart so visitors can walk amongst them.

With this experimental instrument, I am exploring and attempting to emulate the chaotic anima of simple elemental events that universally transfix human attention – flickering fire, sunlight reflected off water, residual rainwater dripping in a downpipe, occasional wind rustle, birdsong, flocking behaviour. The entropophone can be jostled to generate a tangle of clanking cacophony or gently prodded for delicate open melodic phrases. Either way, without further intervention, it will slowly return to silence via ever-decreasing random musical sequences of aluminium song.

an aleatoric ensemble

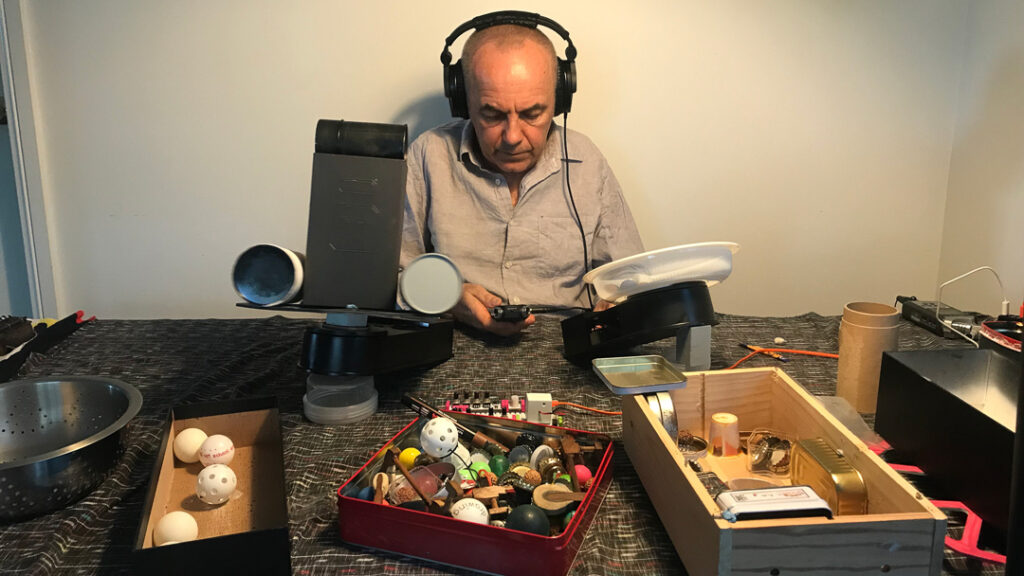

Gary Warner, an aleatoric ensemble, 2016, hacked USB turntables, 9v batteries, dc motor controllers, laser cut plywood, various tins, balls and boxes, rubber bands, santalum acuminatum seeds, marbles, string, bric-a-brac, dimensions variable

“the aleatoric ensemble” is a collection of small modified battery-powered turntables fitted with tins and boxes with bric-a-brac inside them. The combinations change each time I bring them out for performances or recording sessions. As the turntables rotate, the objects roll about and strike surfaces, generating unusual, suggestively musical and percussive sounds in cyclic yet slightly variant patterns. They are a type of analogue sequencer.

The turntable modification is the addition of a DC Motor Controller to enable variable speed RPM (revolutions per minute) by turning a knob. Laser-cut plywood platens, the size of a vinyl LP, are fixed to the turntables. These provide a surface for attaching the ad-hoc arrays of trays, boxes and tins, with various superballs, quandong seeds, marbles, and other small objects inside. The different material properties of the containers and moving objects create diverse sonic outcomes, rich for combinatorial experimentation.

Set in motion, the constructions turn, objects move, balls roll, and surfaces are struck. Each rotation causes similar but not identical sound sequences, often both rhythmic and melodic. Complex soundscapes can be built up by gradually activating multiple turntables. Each instrument/device can be performatively played by making slight variations in RPM and adding or subtracting sounding objects, including ping pong balls, bottle caps, tape dispenser cores, quandong seeds, marbles, superballs, and anything else that might produce an interesting sound.

I have used the aleatoric ensemble in different ways – for performances at Verge Gallery, University of Sydney, Articulate project space, Leichhardt, Cementa Arts Festival, Kandos and at the ORT Festival curated by Kraig Grady at Sydney Non-Objective (SNO), Marrickville. In 2017, I was commissioned to make a soundscape for an urban space in the Adelaide CBD and used recordings of the ensemble, mixed with sounds from my field recoding library, to prepare a series of 45 two-minute compositions that played back at random intervals. In 2022, I worked with the ensemble at a weekly gathering of students at the National Art School, Sydney in a project we called Experimental Sound Circle. And episodes of my Sonic Sketchbooks podcast feature manipulated recordings of various aleatoric ensemble incarnations.

For my 1981 birthday, Brisbane band The Go-Betweens gave me John Cage’s then-recently published book Empty Words because of my predilection for noise over music. I appreciated that gift and still have the book. In 2011, I read Where the Heart Beats, Kay Larson’s biography of Cage. Structured chronologically, the book tracks his ideas, relationships and projects, focusing on Zen Buddhism’s influence on his life and work. So to say, for me, John Cage has been a constant but absent sensei – a lifelong guide.

sonic event generator for gallery wall

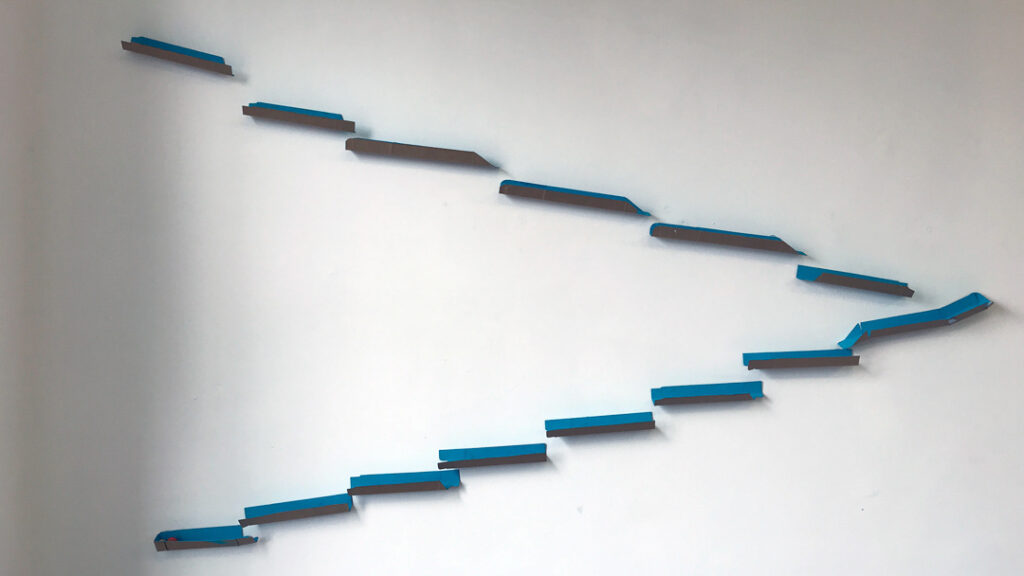

Gary Warner, sonic event generator for gallery wall, 2020, cardboard, aluminium, plastics, quandong nuts, dimensions variable

I am forever experimenting with ways to generate sound sequences using post-consumer waste. For example, Stone Bottle Drop involved forming 3-metre-long tubes from empty 1-litre water bottles. I cut the base from each bottle, joined them using masking tape and suspended a resulting pair of pipes from a first-floor balcony. Another performer and I then rhythmically dropped small quartz pebbles into the top of the tube to rattle percussively down the length and drop into a tub of water or an empty tin.

Then I started folding channels of cardboard and aluminium and attaching them to my studio walls in descending arrays such that a ball dropped into the top channel would travel down the series, sounding as it went.

When invited to show a piece at an end-of-year exhibition at Articulate project space, I made a version responding directly to the architectural form. I folded more channels of different weights and types of card and aluminium and collected and worked small plastic drink bottles and containers. Each material or form was selected for its sonic potential.

At the gallery, I began fixing channels to the wall at the top of a set of stairs, choosing different materials and forms to follow around columns and other surface changes. Near the bottom of the stairs, the last part of the”‘race” was a long thin tin originally made to contain an Italian nougat bar. It served as a receptacle to capture the ball at the end of its brief trip. The container offered up a satisfying kerplunk sound as the ball struck its end and came to a stop.

Ball is not quite the right word. At the top of the stairs was a small box with a few quandong nuts inside. Visitors took one of these to drop in the top of the series. This distinctive spherical nut is from Santalum acuminatum, a small hemiparasitic tree endemic to Australia’s arid interior. The bright red fruit is a hard woody nut surrounded by a thin fleshy membrane, high in amino acids and trace vitamins. This membrane is good eating for humans and animals, such as the wandering emu that spread nuts in their scats. The nut’s journey through the bird’s body is vital to the tree’s germination and distribution. Once swallowed, it is acid-effected and scratched by crop stones in the emu’s gut but remains intact to end up on the ground in a readymade pile of fertiliser.

The woody marble-like quandong nut works well for sounding because of its gyrified surface—bumpy and dimpled like a brain. A smooth-surfaced marble or superball makes much less sound, mainly the percussive strike when dropping from one material to another. A quandong nut sounds as it rolls along as well.

‘sonic event generator for gallery wall’ is a playful analogue sequencer that is each time slightly variant depending on initial conditions and the momentary physics of the nut’s encounters with materials along the way.

Further listening, reading and viewing.

Sonic Sketchbooks visual episode guide

Sonic Sketchbooks episode 18 sonic-kinetic sculptures – 21-pendulum entropophone and others

aleatoric ensemble performance 2016