Dear Adelaida,

Four years ago, I purchased one of your figurines in San Antonio, Texas, from a Mexican folk art store packed with the usual Frida shopping bags, wrestling masks, ceramic jugs and embossed tin picture frames. There were some beautiful arboles de la vida, colourful ceramic trees of life, festooned with birds and flowers on wires, so their leafy canopies shimmered. But these were expensive, and hard to carry. I still had to get back to New Zealand. Venturing into the basement, scanning shelves of dusty trinkets, I saw your work.

Finding an object you adore is like meeting the gaze of a potential love interest. There is a moment of shyness. Could this be the one? You don’t want to look too interested; there is an impropriety in staring too long, too longingly. I sidled closer. Attempting nonchalance, I gingerly picked up your piece and turned it upside down. Your name, Adelaida Pascual, was written confidently across the bottom. A good sign, or so I thought.

Dear Adelaida,

Here’s why I loved your sculpture: you depicted diablitos, little devils, as if they were people like you and me. They were hanging out on a crazy pink park bench, the black diablita eating an icecream, the yellow diablito trying to woo her. In fact, when I got home to New Zealand, my husband asked me if the two figures were supposed to be our portrait. He was making a joke on his ethnicity, and my sweet tooth.

I recall seeing plenty of canoodling couples in Xochimilco, the aquatic park in Mexico City, many years ago. I remember dusty trees, and men carrying sticks festooned with bags of candyfloss, balloons and toys piled so high you could barely see their faces and they looked like they might float away. The coloured boats on the water and the food vendors were superimposed in my mind’s eye over an earlier view of the city. That uncivilised fellow Cortés sent a letter to the King of Spain in 1520, remarking on the neatly arranged islands of the aquatic city of Tenochtitlan, later to become Mexico City. Canoes navigated canals and there were public squares where more than sixty thousand people were daily engaged in selling their wares: fruits and vegetables, honey, agave nectar, fish and eggs. There was gold, silver, lead, brass, copper, tin, iridescent quetzal feathers and precious stones. Every kind of wild bird was for sale, and all kinds of animals (including chihuahua) were raised for meat. There were barbers and restaurants, and a street full of medicinal herbs and apothecaries’ shops. There was cotton in all colours, coloured paints, and – here’s where you come in, Adelaida – pots and painted clay figurines!

Cortés was full of praises for the city he would change forever. Although, gazing out over the lake at Xochimilco, I thought, “it hasn’t changed that much, after all. The vendors still pile high coloured goods, the boats still float, the pottery still charms…”

According to Cortés, it was because Moctezuma’s people had come down to Mexico from Aztlan in the North, that they accepted the imposition of Spanish ways. They were concerned that, having become estranged from their ancestral home, their rituals might have deteriorated. They stood by while Cortés smashed their idols.

Dear Adelaida,

Although I only spent six days in Mexico, I lived in Aztlan for three years. According to a Nahua chronicler of the seventeenth century, the word Aztlan derives from an enormous tree with white flowers called an azcahuitl in the centre of an island. Writing about ceramic trees of life, Delia Cosentino noted that the Aztec empire’s island capital of Tenochtitlan recalled the original island of Aztlan, while a tree stands literally at the core of the Aztec name (which is Nahuatl for the people of Aztlan).

So Mexico City recalls Aztlan, and Aztlan recalls Mexico City. Trees are still important in Aztlan: avocado and the sacred ceiba, with spiky, iridescent green trunks, hot pink star-shaped flowers, and kapok-like pods. There are also palm trees sprouting amidst the billboards en español. Echo Park where I lived was like Xochimilco in miniature, a lake surrounded by candyfloss men and corn guys, dusty trees and lovers. The sacred signs of Mexico City were all around: images of the eagle (and those gringos thought it was their symbol!); plenty of nopales, those cacti the gringos call ‘beaver-tail’; and signs warning about rattlesnakes, although I never saw one. Only 150 years earlier, this was ‘officially’ Mexico, but unofficially, it still is, despite the gringo propaganda machine called Hollywood, that grandiose monument to human sacrifice, greater even than Huey Teocalli, the magnificent Aztec temple upon whose ruins Mexico City now stands.

Dear Adelaida,

I went to San Antonio to see my tejana friend Celia. I had visited her once before, years ago, when we watched Sergei Eisenstein’s ¡Que viva México!, ate huevos rancheros and danced to cumbia. By the time I made my second visit, Celia had completed her training as an architect, and she was working on the restoration of the Alamo. She hated all that Davy Crockett, John Wayne mythology.

Gloria Anzaldúa recounts the whole sorry story in her essay, “The New Mestiza.” “In the 1800s, Anglos migrated illegally into Texas, which was then part of Mexico, in greater and greater numbers and gradually drove the tejanos (native Texans of Mexican descent) from their lands… Their illegal invasion forced Mexico to fight a war to keep its Texas territory. The Battle of the Alamo, in which the Mexican forces vanquished the whites, became, for the whites, the symbol of the cowardly and villainous character of the Mexicans… In 1846, the U.S. incited Mexico to war. U.S. troops invaded and occupied Mexico, forcing her to give up almost half of her nation, what is now Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, Colorado and California.”

Celia cooked me borracho or ‘drunk’ beans with beer, and took me to see the world’s largest bat population streaming out of Bracken Cave. When we went to a local craft gallery, I wondered aloud why the tejano artists making arboles hadn’t included any bats, and Celia said, “That’s your job!” I went home with a head full of ideas, like a cave filled with bats.

Dear Adelaida,

No one knows exactly when or where the candelabra originated, but some surmise it came from the Middle East, that hotbed of monotheism. The Mexican ceramic tradition known as arbol de la vida may have been inspired by the metal candelabras used by Catholic friars at the time of Conquest. Lenore Mulryan wrote that the Spanish clergy fostered syncretic parallels between local traditions and Catholicism as a means of promoting Christianity, commissioning Indian potters in Metepec and elsewhere to create trees of life incorporating Adam and Eve. Well, I guess you knew that already, and Metepec isn’t that far from you in Michoacán. I looked you up on the Internet. Adelaida Pascual González, prize-winning artist.

I hear there’s a lot of natural clay in Michoacán. And that diablito figurines were popularised by a potter called Marcelino Vicente from Ocumicho, Michoacán, in the 1960s. A local myth holds that the devil himself posed for Marcelino so that his likeness could be transfigured into clay. Pottery was women’s work, but Marcelino was a renegade in women’s clothing. Maybe that’s where Grayson Perry got the idea? But this story doesn’t have a happy ending. Marcelino was beaten to death, a victim of hate crime, in 1968 at the age of 35. His style left a grand legacy among the women potters of the town.

Dear Adelaida,

I thought the fact that you autographed your work, and won a prize, were good signs. That was before I read Lucero Ibarra Rojas’s paper on the Ocumicho devils, critiquing the State of Michoacán’s imposition of capitalistic ideas of individualism and competition upon indigenous artisans. Apparently the purhépecha language, spoken by the vast majority of the people in Ocumicho, has no word for I, only we. This paper underlined what I suspected – that the artisans of Ocumicho live in poverty, while their work is globally renown. Many of them don’t even like sculpting devils, but it’s their best means of earning a living. Michoacán has the highest rate of immigration to the US of any Mexican state, and many Ocumicho men are working in Aztlan, driving white pickup trucks, standing outside Home Depot. Some of them never come home.

Dear Adelaida,

I read that pottery was women’s work throughout the Americas. Claude Lévi-Strauss wrote a book about pottery myths across the continent called The Jealous Potter, and stated: “The Indian woman has to fabricate the clay vessels and manages these utensils because the clay of which they are made, like the earth itself, is female – that is, has a woman’s soul.” He was talking about Amazonian Indians, which is a world away from you, Adelaida. But in Zinacantan, which is a little bit closer, softening clay is also a feminine activity, women soften corn for tortillas, and prepare clay for pottery by kneading it. Childbirth is also related to such “softening”, so the analogy between making tortillas and making babies extends to encompass relations between preparing clay and creating humans. It’s the same all over the world. The British artist Anthony Gormley says “It is extraordinary how universal and similar these ideas about creation are – from the book of Genesis, to the Akkadian and Mesopotamian myths, the Nag Hammadi Gnostic gospels and the Chinese creation legends. It’s rooted very deep in our psyche that a god-like figure creates us from the earth and that we return to the earth.”

Marcelino’s encounter with the devil provides a refreshingly perverse twist on Genesis – instead of God making man from clay, man makes devils, which spring up, Pan-like, from the earth – manifestations of the nature spirits that the Catholics tried to crush. Uncanny echoes between indigenous belief systems and Christianity spooked the Spaniards. Cortés was outraged by what he perceived as a bastardisation of Christian communion being performed via consummation of red amaranth paste as the body of the god Huitzilopochtli; he banned both rite and grain. But this just meant that old beliefs continued under the guise of the new, the dark-skinned Virgin of Guadalupe being a Christian mask concealing the pre-Hispanic earth and fertility goddess, Tonantzin, who is associated with rebellion against power figures. Michael Taussig wrote a book about The Devil and Commodity Fetishism in South America, in which he notes that the diablito figure was used by Colombian miners as a symbol of power against oppression. And so it was in early modern Europe, where the devil emerged from popular paganism, and was seen as an ally of the poor in their struggles against landowners and the Church.

Dear Adelaida,

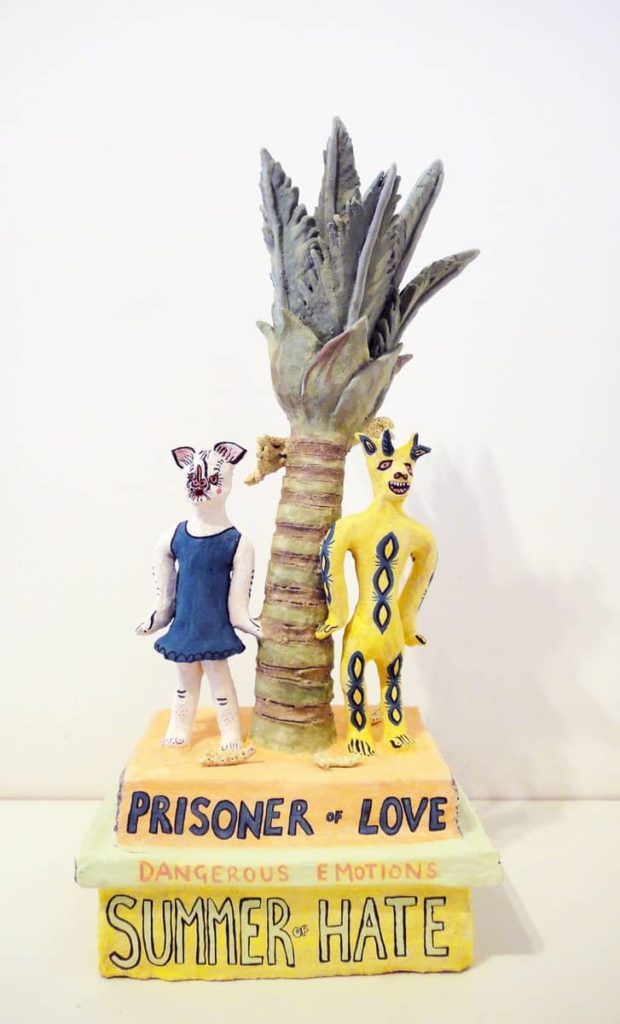

Around the close of 2012, the end of the Mayan calendar that had us gringos so worried, I started making something resembling clay arboles, encrusted with flowers, snails, eyeballs, fruits, frogs, and of course, bats. One day, I made a piece featuring a nikau palm from my country, and standing next to the tree were two diablitos. The yellow male was copied exactly from yours, but the female had turned from black to white, with a wrinkled-up bat face. It was my marital portrait atop a stack of clay books: Prisoner of Love, Dangerous Emotions, and Summer of Hate. Well, we were arguing like diablitos that summer.

I was worried about such direct appropriation. So I scratched into the trunk of the nikau TL + AP – like those lovers’ initials you see carved into the bark of trees, to acknowledge a ‘collaboration’ of sorts. I hope you don’t see it as theft. I told myself I would try to track you down and pay you a percentage if I ever sold the piece. But nobody bought it, despite the fact it was exhibited at the biggest gallery in Auckland. I wrote to Delia Cosentino, an expert on Mexican polychrome art, to ask her about the political implications of my arboles. She said, “As I see it, the Mexican trees themselves represent a series of mixtures, appropriations, and transformations – most recently by the transnational tourist and collector trade, so at its very core there is nothing ‘pure’ about the form. I can see that your artworks are truly rooted in who you are, with a nod to those who have helped to shape your vision.”

No one mentioned cultural appropriation in regards to my exhibition, although one reviewer called my work ‘derivative’ but didn’t say of what. Another described my ceramics as ‘daggy’ and quite a few people called them juvenile. But my friend Xavier, who is Mexican, came with his partner Carolyna all the way from Raglan, and they loved it. They were the critics I was hoping to impress. Them and you, Adelaida.

Tessa Laird, Prisoner of Love, Summer of Hate, 2013, earthenware with ceramic paint, 450 × 220 × 140mm, Photo courtesy Melanie Roger Gallery

This text originally appeared as part of the Objectspace exhibition My Empire of Dirt: Writing About Ceramics in December 2015

Author

Tessa Laird is a New Zealand artist, writer, and lecturer, and recent arrival to Melbourne. Her book on colour, A Rainbow Reader, was published by Clouds in 2013. She is currently lecturing in Critical and Theoretical Studies at the School of Art, VCA, and writing a book about bats.

Tessa Laird is a New Zealand artist, writer, and lecturer, and recent arrival to Melbourne. Her book on colour, A Rainbow Reader, was published by Clouds in 2013. She is currently lecturing in Critical and Theoretical Studies at the School of Art, VCA, and writing a book about bats.