Angela Sim recounts the dazzling festival that honours the Queen of Heaven.

Night falls, and the tide is high

Along Singapore’s East Coast, hundreds dressed in white stand in stillness, their faces lit by lantern glow and moonlight. The sea is dark, restless. From the horizon comes the steady beat of drums—low, insistent—and the glint of yellow silk. Covered palanquins emerge from the water, swaying on the shoulders of barefoot carriers. Curtains ripple in the sea breeze, concealing what they bear. Chants rise, incense thickens, and the crowd leans forward. The Nine Emperor Gods have returned from the Heavenly River, crossing through tide and night to walk among mortals once more.

Celestial Lords of Fate: The Tale of the Nine Emperor Gods Festival

Long ago, in the deep vault of the night sky, nine radiant stars shone with a power beyond mortal reckoning. Seven gleamed in the familiar curve of the Big Dipper, while two others lay hidden, seen only by those who could read the heavens with a Daoist’s eye. These were the Nine Emperor Gods, Jiǔ Huáng Dà Dì (九皇大帝), high celestial lords charged with the gravest of duties: to govern the turning of the planets, to record virtue and vice, and to decide the most delicate balance of all… the allotment of life and death.

Their mother was Dou Mu (斗母), the Mother of the Dipper, the Queen of Heaven herself. A mighty Water Spirit, she commanded the seas and rivers as effortlessly as the stars obeyed her gaze. From her, the Nine received their birthright—the ability to descend from the Heavenly River, cross the great waters, and bring order to the human world. And so, when mortals honour them, it is by water that they are welcomed and by water that they are returned.

Origins Woven from Myth and Memory

In the earliest scrolls of the Han dynasty, whispers can be found of the Nine Human Sovereigns, rulers who bridged heaven and earth. Later, in the Ming era, temple records from Fujian and Guangdong told of grand processions for the Lords of the Northern Dipper. When Chinese migrants set sail for the Nanyang—the Southern Seas—in the 19th century, they carried these stories with them. The deities journeyed alongside them, invisible passengers crossing the waves to Malaya, Singapore, and Thailand.

Wherever they settled, the festival was reborn—its heart still beating with the rhythm of the tides. The gods, like the migrants themselves, would arrive across the water, bringing blessings and cosmic renewal to their adopted shores.

The Festival Begins

- Sea of devotees. Courtesy of Ivan Fu

- Sacred umbrella. Courtesy of Ivan Fu

- Sacred incense. Courtesy of Ivan Fu

- Fire Dragon performance. Courtesty of Ivan Fu

- Dragon boat for send off. Courtesy of Angela Sim

- Dragon boat for send off. Courtesy of Angela Sim

- Colourful palanquin. Courtesy of Jia Wei Lee

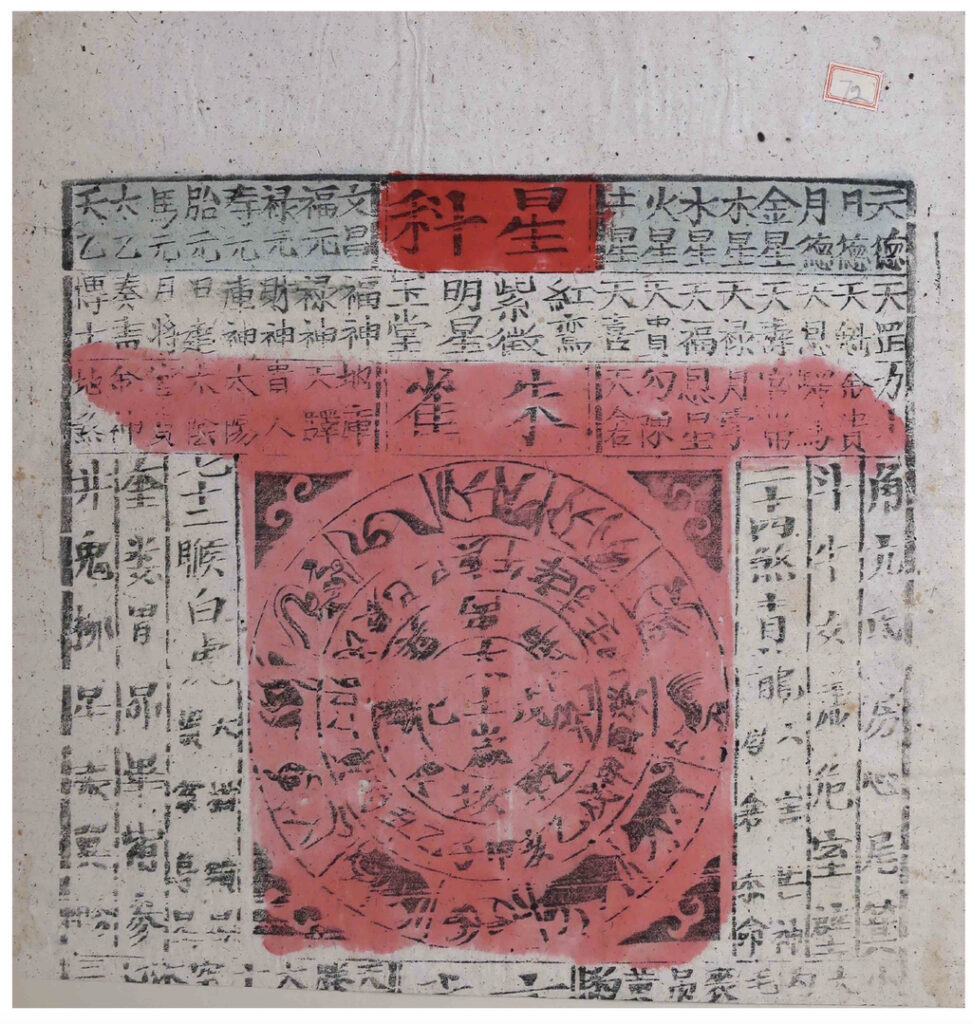

- Astrological Deities. Courtesy of David Leffman

On the eve of the ninth lunar month, the world holds its breath along the shorelines of Singapore, East Coast Park, and crowds dressed in white gather in the hush of the night. The air is cool, the moon silver, the sea whispering against the sand. This is qing shui (清水), the pure water night, when the Receiving of the Nine begins.

From the dark waters, covered palanquins emerge, swaying on the shoulders of devotees. Curtains conceal the divine presence within—the gods’ essence too sacred to be exposed to mortal eyes. Barefoot worshippers, some in trance, bow as incense coils burn and chants drift out over the waves. It is said the Nine have crossed the Heavenly River, the Milky Way, to walk among humankind once more.

For nine days, the temples thrum with devotion. Lanterns glow not red, but yellow, the colour of sanctity, while the air carries the fragrance of vegetarian offerings. Devotees in white and yellow keep to strict purity: no meat, no pungent foods, no indulgence. The festival is not simply an act of worship; it is a cleansing of body, mind, and spirit.

The Sacred Palanquins

The Nine Emperor Gods travel in enclosed palanquins, each one a moving sanctum. Attendants shield them with flags, umbrellas, and silk screens, for to see them openly would diminish the mystery and reverence that surrounds them. When sacred objects are placed inside, the exchange is done swiftly and discreetly. An unspoken pact between heaven and earth that the holy shall remain veiled.

The Farewell by Sea

On the ninth night, the tide turns. Crowds gather once more by the water for the Sending-Off Ceremony (Sòng Jiǔ Huáng, 送九皇). Palanquins gleam under lantern light, and paper boats heavy with offerings are set aflame, their small fires drifting into the dark sea. The gods return to the waters they came from, carrying petitions, prayers, and the year’s accumulated karmic balances back to the celestial realm.

In Singapore, this farewell is so grand that roads are closed, traffic halted, and temple grounds transformed into glowing cities of tents, stalls, and shrines. The night belongs to the gods and the faithful who walk them to the shore.

Why the Festival Endures

To the uninitiated, the Nine Emperor Gods Festival is a spectacle—processions, incense, chanting by the sea. But to those who know, it is a cosmic renewal: a rebalancing of yin and yang, a resetting of the moral register, a tide that sweeps away the old year’s misfortunes and sets the course for the next.

Even as cities grow and rules change, the rites adapt. Palanquins now move through managed road closures, and urban beaches stand in for old rivers and canals. Yet the essence remains: the journey by water, the purity, the veiled mystery of the gods.

In Thailand’s Phuket, the festival has taken on its own fierce form—acts of piercing and extreme asceticism—but still, the same nine lords are honoured.

And so, year after year, under the same stars that once shone on ancient China, the festival binds together heaven’s lights and earth’s waters, ancient memory and present devotion. In every wave that laps the shore, in every lantern lit against the night, the Nine Emperor Gods keep their vigil: guardians of fate, ferrymen between the cosmic and the human, returning always to the sea from which they came.

References

- Needham, J. (1959). Science and Civilisation in China, Vol. 3. Cambridge University Press.

- Tan, C.B. (1988). The Nine Emperor Gods Festival in Malaysia. Penang: Pelanduk Publications.

- Kong, L. (1999). Culture, Economy, Policy: Cultural Industries and Cultural Policy in Singapore. Geoforum, 30(4), 409–424.

- Ming Shi (明史). Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju.

About Angela Sim

Angela Sim is an Australia-based researcher of Asian heritage and culture. She uses her platform as a media content creator to explore areas such as folk religion, Peranakan culture, and sunset industries, including Chinese woodblock printing, effigy restoration, and lantern making, to name a few. Watch youtube.com/@HakkaMoi

Angela Sim is an Australia-based researcher of Asian heritage and culture. She uses her platform as a media content creator to explore areas such as folk religion, Peranakan culture, and sunset industries, including Chinese woodblock printing, effigy restoration, and lantern making, to name a few. Watch youtube.com/@HakkaMoi