Douglas Black, Our House, 2018, black stoneware 1280°C, enamel, and luster overglaze, H. 15.3 x W. 33 x D. 14.8.

Liliana Morais explores the world of a US-born ceramicist who gives expression to planetarity from his self-built house in the mountains of Japan.

Douglas Black is a US-born Japan-based ceramic artist whose work has encouraged me to think deeper about the relationships that artists establish with the places they come to inhabit, either by fate or by circumstance. I first met Black on a cold winter late afternoon almost ten years ago, at his home and studio in Motegi, where I was brought by friends of friends who were also resident potters in the region. Motegi, where Black has been living and working for three decades now, is a town neighboring Mashiko, the folk pottery center made popular by Hamada Shoji in the 1920s through his connection with Yanagi Soetsu, the philosopher behind the Japanese folk crafts movement (mingei), and British potter Bernard Leach.

Black built his home and studio by himself over the course of the years, using salvaged and recycled materials. It was only after I visited him for a second time, several years later, that I came to realize that his bRIVERb studio and gallery is located just a few yards up the beautiful Naka River, which springs in the mountains of Nasu, a famous hot spring region. Before setting up residence in his current location, Black lived in an abandoned straw thatched-roofed house by the shores of the same river, in which he bathed in the summer and used an old washing machine filled with heated water in the winter. The design of his current home and studio draws on California’s 1970s hippie houses, with its eclectic choice of colors and patterns used in the interior decor, and large windows allowing the surrounding nature and sunshine to flow in.

Black is a calm, soft-spoken individual, who prefers to save words for thoughtful insights only, at least most times. Much of his recent ceramic work, however, is vibrant and colorful with a pinch of glamour and mystery, much like his own home. The artist often applies gold and glaze made from cherry blossom ashes that becomes a beautiful deep blue to the surface of his pieces, reminiscent of the opulent folding screens of the renowned Kano school of painting, the longest in Japanese history. His combination of gold with blue, red, and sometimes purple glazes and overglazes evokes the exuberant and aristocratic taste of Kyoto and Kutani pottery styles, though Black brings the tone down by applying the coloring onto a black clay background, giving it a cosmic feel. Instead of birds, flowers, and other seasonal motifs typical of traditional Japanese ceramics, Black adds a psychedelic touch through the infusion of repetitive patterns, such as spirals, waves, zigzags, polka-dots, and other meandering lines. His mark, which he stamps to the bottom of his pieces, resembles the ancient symbol of sacred geometry, the Vesica Pisces, and stands for cell division.

- Douglas Black, Cosmic Guardian, 2018, Black stoneware 1270°C, enamel and luster overglazes, H. 51 x W. 26.5 x D. 6.5 cm

- Douglas Black, Seto-guro chawan, 2017, H. 8.5 x W. 12.6 x D. 12.3

Black’s earlier work draws on the Japanese aesthetics of wabi-sabi, derived from the distinctive taste of sixteenth-century tea master Sen-no-Rikyû, in his use of locally-available raw materials to produce irregularly shaped wares with subdued-colored glazes, such as the renowned blueish-green celadon, the white milky Shino, and the glossy black Setoguro, the later achieved through the use of the hikidashi technique, all of which are highly valued in the tea ceremony to this day. In fact, Black still produces simpler undecorated vessels for Japanese cuisine (washoku) and the tea ceremony (chadô), which he studies. However, his more recent series, Polka Dot Skies, incorporates the elements that Japanese art historian Nobuo Tsuji (2018) identifies as the three pillars of Japanese art: animism, playfulness (asobi), and adornment (kazari).

Douglas Black, Cosmic Egg, 2017, black stoneware 1280°C, enamel and luster overglazes, H. 33.3 x W. 37 x D. 30.2cm

To these elements, Black adds a cosmopolitan and multimedia approach, a result of his transnational trajectory and artistic training at the Columbus College of Art and Design, in Ohio, where he worked as an assistant to US-based Japanese ceramicist Ban Kajitani (1941-). It was during this time that Black started to explore the chemical and geological aspects of clay, experimenting with all types of earthly stones and minerals like an otaku, as he put it. This approach to making not only embodies the “animistic” attitude that Nobuo Tsuji speaks of, but it is also a reflection of the material-led attitude that Japanese craft theorist Kaneko Kenji calls “craftical formation”, which departs from a deep knowledge and respect for the materials rather than from a pre-conceived project.

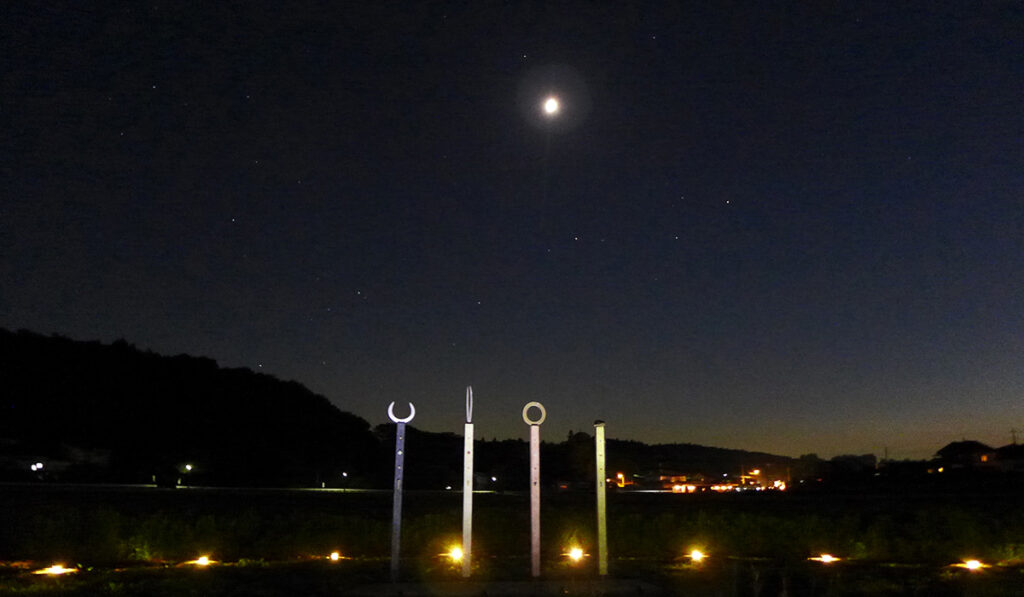

The desire to explore the possibilities of various materials, such as clay, metal, wood, glass, and stone also reflect Black’s playful attitude to making. His animistic ethics is again visible in his desire to understand and “play with” the “language” of each material, as he described. He often does so in his large-scale installations, such as the installation work he presented during the third edition of Hijisai – Living with the Earth Festival, held in Mashiko in 2015. Drawing on the element of earth (土 tsuchi) as a guiding thread, Hijisai highlights the importance of the soil as a vital resource for both community’s central historical activities: pottery and agriculture. To this, Black added a third significance: that of the Earth as the planet in which humans from all races and cultures must coexist Under One Sky (title of the work). The 25-meter-wide spatial solar installation comprised of four 3.5-meter-tall totem-like sculptures and small alien-looking figures made in ceramics and other materials were set up on a rice field, evoking the rituals humans would have engaged in during cultivation and harvesting in ancient times.

- Douglas Black, Under One Sky, Hijisai, 2015, solar installation, earth casting, stones, ceramic, steel

- Douglas Black, Celestial Witness, 2014, black stoneware 1280°C, enamel and luster overglazes, H. 9.5 x W. 25 x D. 5 cm

Black’s synthesis of working and living in and with the land is reminiscent of the mindset fostered by 1970s counterculture, which experimented with handicrafts far from the large urban centers, inspired by the early Arts and Crafts and back-to-the-land movements and their often-nostalgic praise of the slow and simple rural life. Black is less romantic in his view of the surrounding natural environment, however. During the three decades that the artist has lived in Motegi, he has experienced various disasters, including the Great Eastern Japan Earthquake in 2011, which damaged hundreds of pottery kilns in the area. Luckily, his house was left intact, but in 2019 his beloved Naka River flooded the neighborhood and, last year, it barely escaped a fire that spread in his studio. This experience of both the enchanting and the potentially destructive power of nature translates into the humble attitude in which he approaches the materials and place he works with.

In 2013, Black visited the headwaters of the Naka River that flows by his house during a three-month artist-in-residence program at Art Biotop, which is located at the foot of Mount Nasu. When he first discovered Naka river’s spring, it was like “going back to the source, my source too”, the artist declared during one of the various hours-long interviewees I made him go through for my Ph.D. He continued: “I think one of the reasons why I’m in Japan is because of this place here”. During that artist-in-residence, Black used ceramics, glass, and driftwood found in the river to create warrior-like figures that represent the protective spirits of the future of the river, as well as forms reminiscing spear points and arrowheads, connecting past and future.

- Naka river seen from Douglas Black’s neighborhood.

- Douglas Black. River of Dreams, 2014, driftwood, stones, glass, ceramic, H. 19 x W. 145 x D. 6 cm

The artist’s work often draws on ancient themes, figures, and symbols from many different places, times, and cultures around the world. Some works are reminiscing of the Ancient Syrian eye idols, Egyptian cats, or cow-shaped African masks, while others expand on cosmological themes, such as stars, planets, and crescent-moons. His “archaeological cosmopolitanism” (as I decided to call it) blends nostalgia and futurism, drawing on humanity’s collective memory of the past to imagine a utopian future where “the races that live together on this planet” (from Black’s installation Remember the Future, Hijisai 4th edition, 2018. The artist created an installation with four colored clay walls and a glass bowl symbolizing gratitude).

The desire to tear down racial and national borders is a natural result of the artist’s own background and trajectory in between two countries and cultures. In 2021, he travelled to New Mexico for a joint exhibit with Doug Coffin, his godfather, namesake, and a successful Native American contemporary artist, who has also been a major influence in Black’s artistic trajectory. There, at Ellsworth Gallery in Santa Fe, the artist exhibited horn-shaped sculptural works and his deep-blue glazed Icarus figures, alongside Coffin’s monumental sculptures and other mixed-media works.

Black’s work also tears down the boundaries between the artificial and Eurocentric division of art and craft (see Shiner, 2001). Often confronted by the question of whether he is an artist or a potter, Black insists he is both. As a reaction to this recent but enduring split between the expressive and the functional, the spiritual and the utilitarian, Black coined the term “heartist” to refer to himself and his work made by hand with sincerity (from the heart). Merging the warmth and practical function of a teacup, flower vase, and other everyday utilitarian objects, with the spiritual function of human creative expression, which he considers to be a vital one, Black draws on clay’s history as a primordial earthly element and one of the first materials humans manipulated to the shape of our imagination. Reflecting our ancestors’ awe for the natural forces, working with clay offers possibilities that are “as infinite as the universe of its composition” (Artist Statement).

Douglas Black, Ikarus Dreaming, 2018, black stoneware 1240°C, enamel and luster overglazes, H. 35.5 x W. 38 x D. 6.4cm

Douglas Black’s life and work, which are one and the same, reflect his standing as a citizen of the Earth, or “Earthling” as he jokingly likes to call himself. This self-ascribed planet-bound ecological position, though in a world divided by artificially drawn borders and manipulated news, relates to the concept of “planetarity” as expressed by influential postcolonial scholar Gayatri Spivak (2003). Planetarity is grounded on the idea that all human and non-human beings who share a home on our planet Earth, in its transnational natural form, are interdependent and interconnected. In a world where we are as ever connected yet increasingly divided, Douglas Black’s created his Polka Dot Skies series, reminding us that “we are all dots connecting the universe” (Artist Statement). So, let’s toast to the past that survives in the present in the form of clay, gold, and ashes.

About Douglas Black

Douglas Black is an American artist based in Japan since 1990. His works embrace both function and wonder, celebrating the cultures mindful appreciation to the presentation of food, spirits, tea, and our flower friends, while his sculptures explore the ceramic palette, ground to the planet and reaching to the stars like those before us. After receiving his BFA from the Columbus College of Art and Design, Black was awarded an Artist Visa by the Foreign Ministry of Japan. Bonding with a Tokyo based visionary, he produced stage art design for fashion movements, music performances and ambient opera before establishing himself as a ceramist. Black exhibits annually and has accepted many invitations to work alongside international artists overseas. In 2017, his ceramic art was awarded Grand Prix in both Tokyo and France. He was gifted a studio in Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur to produce works for a solo exhibition at the La Maison de la Céramique Terra Rossa in 2018. Other works include installations of various medium. Black has participated in the triennial, Earth Art Mashiko HIJISAI, an earth festa that coincides with the harvest moon and living with the earth. In 2015, he made an outdoor solar installation Under One Sky and an indoor installation, Remember the Future, in 2018. In the most recent edition of the festival, held in 2021, Black exhibited a third installation work set on ancient temple grounds titled All Are One. Follow @b_river_b/

Douglas Black is an American artist based in Japan since 1990. His works embrace both function and wonder, celebrating the cultures mindful appreciation to the presentation of food, spirits, tea, and our flower friends, while his sculptures explore the ceramic palette, ground to the planet and reaching to the stars like those before us. After receiving his BFA from the Columbus College of Art and Design, Black was awarded an Artist Visa by the Foreign Ministry of Japan. Bonding with a Tokyo based visionary, he produced stage art design for fashion movements, music performances and ambient opera before establishing himself as a ceramist. Black exhibits annually and has accepted many invitations to work alongside international artists overseas. In 2017, his ceramic art was awarded Grand Prix in both Tokyo and France. He was gifted a studio in Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur to produce works for a solo exhibition at the La Maison de la Céramique Terra Rossa in 2018. Other works include installations of various medium. Black has participated in the triennial, Earth Art Mashiko HIJISAI, an earth festa that coincides with the harvest moon and living with the earth. In 2015, he made an outdoor solar installation Under One Sky and an indoor installation, Remember the Future, in 2018. In the most recent edition of the festival, held in 2021, Black exhibited a third installation work set on ancient temple grounds titled All Are One. Follow @b_river_b/

Artist Statement

My works are inspired from nature and the beauty of our mystery. Within the timeless art of clay and fire comes a sense of connection to common spirits who have created ceramics throughout history, spiritually and functionally. Along the ceramic process accidental discoveries happen. These fascinations can open as doors into new series. One motif in my sculpture is of guardians protecting our future, grounded, yet rooted in dreams. I often include energy marks or symbols that thread the past into the future.

The possibilities with clay are as infinite as the universe of its composition. Not long ago, a spacey colored polka dot made from the ash of a cherry blossom tree was discovered on black clay. A new series, Polka Dot Skies, began…

We are all dots connecting the universe.

References

Black, Douglas. Homepage: https://douglasblack.indiemade.com/

Black, Douglas. Blog: http://www.douglasblackart.com/

Kaneko, Kenji. 2002. “Studio Craft and Craftical Formation”. In The Persistence of Craft: The Applied Arts Today edited by Peter Greenhalgh. London: A & C Black Publishers Ltd.

Shiner, Larry. 2001. The Invention of Art: A Cultural System. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty. 2003. Death of a Discipline. New York: Columbia University Press.

Tsuji, Nobuo. 2019. History of Art in Japan. New York: Columbia University Press.

About Liliana Morais

Liliana Morais holds a B.A. in Archaeology and History from the University of Lisbon (2007), an M.A. in Japanese Culture from the University of São Paulo (2014), and a PhD in Sociology from Tokyo Metropolitan University (2019). She is currently an Adjunct Professor at various universities around Japan. She was a curator of the exhibition From Japan to Brazil: the Voyage of Oriental Ceramics, held at Caixa Cultural Salvador. In 2014-5, she worked as a research collaborator at the Cunha Ceramics Cultural Institute, where she published the book Cunha Ceramics: 40 years of Noborigama kiln in Brazil (ICCC, 2016, in Portuguese). As a researcher, she is interested in looking at art and material culture through the lens of mobility, transnational migration, and transcultural exchanges. Her scholarly work is based on qualitative research methods such as ethnographic fieldwork, participant observation, and oral history.

Liliana Morais holds a B.A. in Archaeology and History from the University of Lisbon (2007), an M.A. in Japanese Culture from the University of São Paulo (2014), and a PhD in Sociology from Tokyo Metropolitan University (2019). She is currently an Adjunct Professor at various universities around Japan. She was a curator of the exhibition From Japan to Brazil: the Voyage of Oriental Ceramics, held at Caixa Cultural Salvador. In 2014-5, she worked as a research collaborator at the Cunha Ceramics Cultural Institute, where she published the book Cunha Ceramics: 40 years of Noborigama kiln in Brazil (ICCC, 2016, in Portuguese). As a researcher, she is interested in looking at art and material culture through the lens of mobility, transnational migration, and transcultural exchanges. Her scholarly work is based on qualitative research methods such as ethnographic fieldwork, participant observation, and oral history.

Comments

Great article about a great heartist !