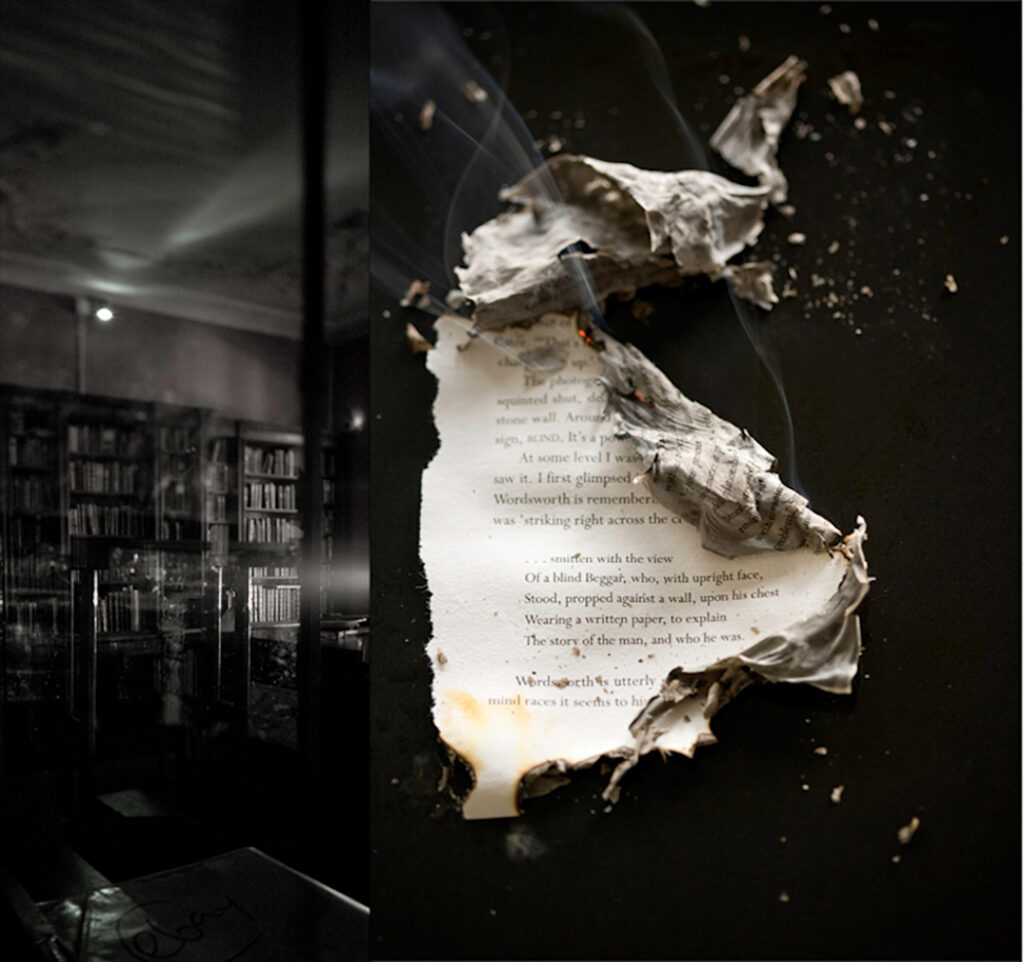

Paul Schütze, In Libro de Tenebris, 2014, Fragrance – quarto antique book, black ink; created as part of Silent Surface – an exhibition of photographs at Maggs Gallery – London 2014

In presenting an exhibition of photographs, Paul Schütze decided to add an olfactory dimension, which opened doors into another time.

In August 2014 I was preparing a small exhibition of photographs I’d shot in one of Europe’s oldest, antiquarian, bookshops.

Maggs had been established in the 1850s and based in Berkeley Square since 1938. Across its three floors, It offered an astonishing collection of rare and valuable books. Reaching further below the square, in the apparently endless basement spaces, they held an even more astonishing body of stock in varying states of dishevelment.

Over the previous few years, I had been working on photographs (Nocturnes) of museum collections and archives, photographed at night in whatever light was available. I wanted to depict the buildings and their contents as a unified environment/material, without the hierarchies of lighting and display in their contemporary incarnations. Having completed shooting in several locations including the British Museum, The Soane’s and the V&A, I had become intrigued by Maggs after exhibiting in their gallery space the previous year.

After some days preparation, trying to anticipate the illumination I might work by once the house lights were extinguished, and generally immersing myself in this weird parallel zone of antique documents, I began my shoot. On the first night, the upper floors were well illuminated by the fizzing overspill from street lights in Barkley Square. The lower floors and the basement were more of a challenge. Sometimes a lone shaft of watery light pushed its way to the mouldering stacks, spilling across the flagstones or onto the endless, precarious, shelving. The rest of the space was a pregnant gloom, impenetrable, even to my hyper-sensitive digital cameras. Over two nights, I documented what I could and gained a feel for the very particular “matter” of the place.

I was very happy with the final images, often combining them with details shot from the pages of some of the books themselves. It was decided the final prints would be shown in what were originally the old stables in the Mews at the back of this, once grand, Georgian house.

As I worked on developing the images, I began to feel strongly that there was something crucial absent in my evocation of the subject. After some time I realised it was the almost tactile olfactory presence, generated by the collected, aging, books. One thing I couldn’t document was this singular, intoxicating fragrance. Layered and weighty, this perfume came to distil the place more completely than any other sensory record.

The almost physical, “mass” of leathery, sour, powdery, funk, nestled into your nose and clung to your clothing like a fragrant fog. I smelt its ghost when looking at the pictures and wanted others to share its phantom touch. In the space, it felt almost like another material part of the building rather than the void it appeared in the photographs

I’d keenly felt this olfactory absence when showing works I’d created to evoke architectural spaces. On some occasions I’d used sound to augment a suit of images, on others, designed spaces to introduce movement into the viewing/listening experience but always lamented that olfactory elements (ubiquitous, deeply evocative, and defining) were outside either my skill or my budget. Despite a long-standing bias in the artworld against poly-sensory engagement (the bizarre, twentieth-century idea that sculpture, for example, may only be looked at, the conspicuous absence of exhibition spaces that are isolatable acoustically or olfactorialy) I feel strongly that limiting any experience to one or even two of our dozens of senses somehow folds the world down into too few dimensions. Denying olfaction also denies the activation of memory and affect in a way that I think may, in time, come to seem quite perverse.

On this occasion, there was a delay of a few months between making the images and exhibiting them. I wondered if I might attempt to create a fragrance myself. It was a small show, if it didn’t work then nothing ventured….

I’ve been obsessed with perfume and olfaction for as long as I can remember. I had a modest collection of fragrances and a pretty comprehensive knowledge of what had been created and available commercially over the last few decades. This was however accompanied by a mystified reverence for the perfumer’s art and a certainty that it was and would remain entirely beyond my abilities unless I were to submit to a lifetime of study or apprentice myself to one of the big perfumery houses.

For most of the last century, this was an impression keenly reinforced by the industry itself: perfumery as a discipline akin to alchemy in its secrecy and exclusivity; even the perfumers were secret: a trend really only broken in the last couple of decades as marketing departments have realised noses can be elevated to usefully mythic status. Nonetheless, for the purposes of a tiny exhibition, I would try to create something that animated the olfactory dimension of my subject.

I began, blindly, to order essential oils online. Some of these I knew, at least in theory, others I’d never smelt. Of course, their strength and quality were a mystery until they arrived in the post. This process of trial and error, and bear in mind at this point I was just trying to establish a pallet from which to work, was expensive, time-consuming and largely futile. I took delivery of many bottles of unusable, poor-grade, or wildly inappropriate oils.

Buying materials you cannot smell first is crazy and I knew it, but didn’t think I had another route into the process. Of course, I was totally unaware that there were places from whom I could purchase high-grade materials, which supplied esoteric oils and customised synthetic molecules, built expressly to imitate or augment natural aromatic extracts. Materials of such swooning loveliness I would in time become addicted just to sit for hours, unscrewing their caps and inhaling the worlds they conjured.

I was eventually thrown a lifeline in my efforts by a small stall, present one day a week, and hidden in the grounds of a church on London’s Piccadilly. The owner specialised in very high-quality essential oils imported from countries that excelled in their production. Omani frankincense, Turkish and Bulgarian rose, French lavender, Italian bergamot and petitgrain, Spanish Lentisque.

I was actually able to smell these before I bought them. During hours spent exploring his stock, I’d get flashes of what I was trying to capture for the show from certain bottles and immediately purchase them.

Blending them was something of a mountain to climb. Having zero organic chemistry knowledge and no clue as to the behaviour of combinations of complex olfactory molecules, there was a huge amount of trial and error. I made about seventy variations of my chosen materials before I got close to something that worked. But, to my surprise, I did arrive at a point that, for me at least, evoked the wonderful olfactory presence of the books I’d photographed and indeed the spaces that contained them.

Smell is like a kind of spacial/temporal cartography: but with maps that, like tesseracts, fold and collapse in ways that take them beyond the reach of language.

What I didn’t expect was the complexity of this evocation. It was always changing: flickering glimpses of precise feelings, of textures and materials, of images, coalescing and dissolving on every inhalation. The process was teaching me so much about the role of olfaction in the creation and recollection of impressions. It is one thing to observe this but quite another to feel it change as you manipulate materials. Smell is like a kind of spacial/temporal cartography: but with maps that, like tesseracts, fold and collapse in ways that take them beyond the reach of language.

When you begin to build things in this medium rather than just noticing them, you tap into the circularity of creative time. The place where cause and effect become interchangeable, faceted things. Things that have not yet happened are present as memories, memories as premonitions. Movement becomes more important than thinking, emerging from/located by, objects distributed or just recalled. Feelings crystalise as patterns in place as much as moments in time. A photograph taken a year ago smells like the depicted location a year hence. A fragrance proposes a tree, standing outside the bookshop’s future location, unknown for nearly a decade after the image was made.

Making a perfume, even my first, fanned my senses into an articulated polyphony where there had been a monolithic kind of stasis.

But, how to deliver this fragrance into the exhibition space without overwhelming the visitor or the photographs. How to keep this poly-sensory presence in balance for multiple viewers ….?

Olfaction is a highly complicated mechanism. Both in the ways it acts upon the body and the ways it is processed by the brain. These complications give rise to a high level of subjectivity in the perceiver and significant variations in the tolerance of olfactory stimuli. One person’s delight may be nausea to another. Too strong or too dense and it risks becoming an assault rather than an invitation. The appeal to memory, particularly, is supremely subjective, unpredictable and chaotic.

Smell cannot be broken down into simple axes like colour (hue, saturation, brightness) or sound (timbre, pitch, amplitude). The scientific philosopher Andreas Keller suggests that rather than the three characteristics needed to locate both colours and sounds, an aroma would require around four hundred “dimensions” to accurately specify. Science is not even agreed upon exactly how olfactory perception works. There is a majority view that it involves shaped receptors in the nose that register sympathetically shaped molecules in the air but there is another theory championed by Luca Turin that involves vibration and quantum behaviour. I suspect it’s likely that both play a part.

Fragrancing a space in which you hope to affect the feelings of multiple people sympathetically, needs to be done with care and deference. Unless the smell itself is the sole artefact on display, it is akin to scoring a film. If the score is really working, you should not notice it as distinct from any other part of the experience. Ideally with a true polly-sensory artefact, one hopes that no element overrides the others. Again, the idea of sensory polyphony as opposed to the currently exhausted “multi-sensory” notion in which added “stuff”, regardless of its real relationship with all the other “stuff” is somehow an end in itself.

I didn’t want to use an electronic diffuser as the small space would guarantee the mechanism would be audible. The small space also meant that whatever solution I found would also be visible so….

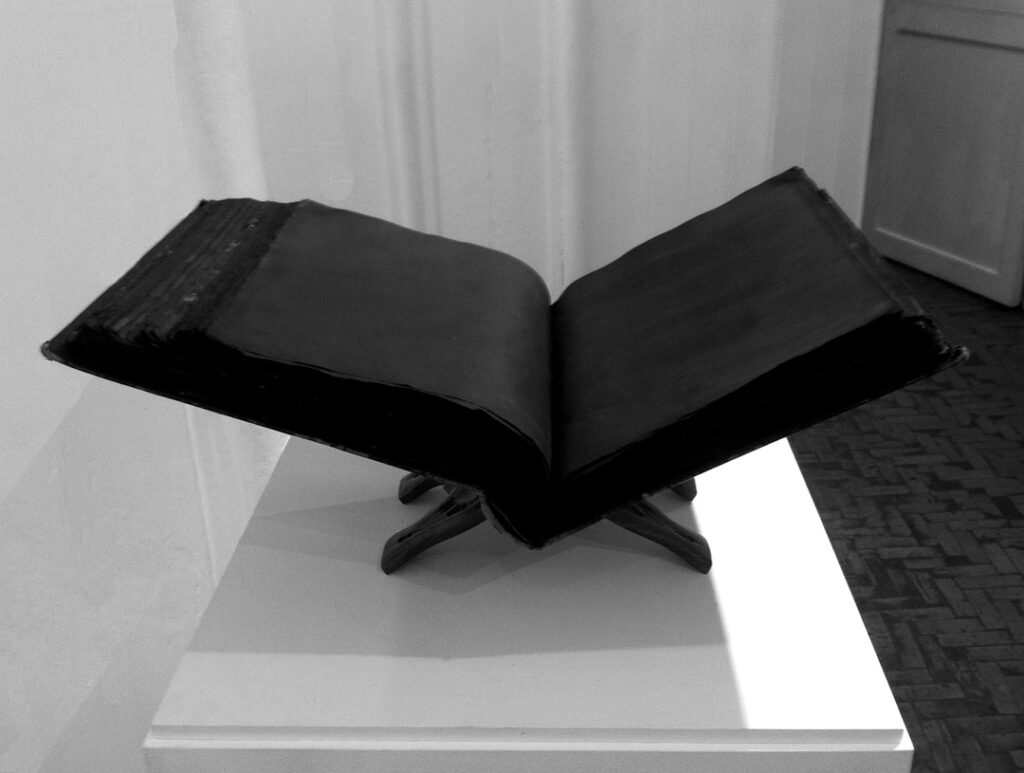

I had the idea to purchase a large, old book (a quarto history of London) stain all of the pages jet-black with the deepest inks I could find so they could no longer be read and then, to fragrance each page so that, when open, the movement of air across the fanned pages would encourage the fragrance to gently permeate the space.

It took weeks to treat the book as each page had to be coated in several layers of ink, back and front while being held apart from the rest of the book to dry. The desiccated paper drank in two litres of ink before it was sated.

Once it had dried completely I coated each page with the perfume, laid it out on a lectern and waited for it to “radiate”.

Paul Schütze, In Libro de Tenebris, 2014, Fragrance – quarto antique book, black ink; created as part of Silent Surface – an exhibition of photographs at Maggs Gallery – London 2014

It worked far better than I’d hoped and the material of book itself seemed to be the origin of this perfume: the blackness of the pages generating the aroma to replace their buried text, while alluding visually to all the other pages depicted in the images around it. The fragrance was present in the space but as a hue rather than a feature. Some people noticed that it emanated from the book and bent down to smell it closely. Others ignored it.

But, not only did it dress the air of the gallery space, the fragrance seemed to reconfigure the room’s geometry in imitation of those darker, more complex spaces seen in the night-time photographs. Talking to visitors weeks afterwards, several remembered, wrongly, having visited the basement spaces on the opening night, though no one did.

About Paul Schütze

Paul Schütze has worked for forty years as an artist in the fields of, sound, photography, video, and installation. He was a founding member of Australian experimental band Laughing Hands and of Phantom City: an international collective of musicians working both live and virtually from points across the globe. He has performed with sound & film works in over a dozen countries and released over thirty albums of original music. Over the decades he has worked with Bill Laswell, Simone de Haan, Toshinori Kondo, Clive Bell, David Toop, Dirk Wachtaeler, Jah Wobble, Raoul Björkenheim, Andrew Hulme, Max Eastly, Robert Hamson, Thomas Köner, Lol Coxhill and Alex Buess. His artworks have been exhibited in numerous international galleries and museums. He has also worked with artists including James Turrell, Josiah McElheny & Isaac Julien. In 2014 Paul began to develop olfactory elements for his exhibition Silent Surface, creating a perfume called In Libro De Tenebris. In 2016 He launched fragrance house Paul Schütze Perfume with partner Chris Rickwood. In 2022 they relocated from London, home for the thirty years since Paul moved from Australia, to the Kent coast. Paul is currently developing a book on sensory ecology.

Paul Schütze has worked for forty years as an artist in the fields of, sound, photography, video, and installation. He was a founding member of Australian experimental band Laughing Hands and of Phantom City: an international collective of musicians working both live and virtually from points across the globe. He has performed with sound & film works in over a dozen countries and released over thirty albums of original music. Over the decades he has worked with Bill Laswell, Simone de Haan, Toshinori Kondo, Clive Bell, David Toop, Dirk Wachtaeler, Jah Wobble, Raoul Björkenheim, Andrew Hulme, Max Eastly, Robert Hamson, Thomas Köner, Lol Coxhill and Alex Buess. His artworks have been exhibited in numerous international galleries and museums. He has also worked with artists including James Turrell, Josiah McElheny & Isaac Julien. In 2014 Paul began to develop olfactory elements for his exhibition Silent Surface, creating a perfume called In Libro De Tenebris. In 2016 He launched fragrance house Paul Schütze Perfume with partner Chris Rickwood. In 2022 they relocated from London, home for the thirty years since Paul moved from Australia, to the Kent coast. Paul is currently developing a book on sensory ecology.