- Mai, Nantu wama Northern Plains, 2018, slow cooked kangaroo, indigenous spices and saltbush on a johnnycake

- Mai, Yatala Swamp 2018, Wild duck seasoned with indigenous spice on steamed bulrush and warrigal greens with river mint mayo served on a whole wheat johnnycake.

- Mai, Wauwi Beach 2018, Goolwa cockle cooked in sea parsley and butter sauce served on seablite and samphire topped with dried seaweed and mayo served on a johnnycake

- Mai, Pangka Lake2018, Coorong Mullet with coastal rosemary topped with fingerlime mayo, saltbush on a johnnycake

- Mai, Kauwa Cliff 2018, Crayfish, Australian coastal greens and finger lime mayo top with dried seaweed on a johnnycake.

- Mai, Tarnta Wama Southern Plains 2018, Kangaroo, indigenous spices, saltbush and quandong on a johnnycake

Prompted by the experience of foraging in Europe, Caitlin Eyre accompanies James Tylor on a quest to recover the taste of native Australian bush foods.

Several years ago, in a forest clearing in rural Sweden, artist and close friend James Tylor stood next to me as we hungrily picked bilberries during our meandering day hike. James paused between mouthfuls to turn to me and ask, “Why aren’t we foraging for native foods back home? Should we try?”

It was an apt question. Here we were, in a country that we were strangers to, and yet (after a quick online search) we felt entirely comfortable foraging and eating berries in these foreign lands. It had been an ongoing theme of our hiking trips throughout Italy, Germany, Denmark and Sweden that summer. We would frequently stumble across currants, bilberries, lingonberries, blackberries, raspberries and tiny Alpine strawberries, enjoying the unexpected bounty. In the Czech Republic, our friends had taken us into the woodlands to forage for mushrooms, relying on the knowledge their grandparents had imparted to them in early childhood to guide our selections.

With our mutual enthusiasm for bushwalking and foraging, which in our home city of Tarntanya Adelaide had previously been confined to introduced wild foods such blackberries, plums, apples and chestnuts, the way forward suddenly seemed clear. Our adventures in foraging native Australian foods were to become the cornerstone of our friendship and a personally enriching journey of engagement with the land and culture of the Kaurna people. For James, a man of mixed Nunga (Kaurna Miyurna), Māori (Te Arawa) and European (English, Scottish, Irish and Norwegian) ancestry, foraging was a powerful means of expanding his lived cultural knowledge, expressing his cultural identity and using Kaurna language to decolonise the landscape. For me, as a non-Indigenous Australian, foraging has given me the opportunity to gain some insight and knowledge of the Aboriginal land (Peramangk and Kaurna Yarta) on which I live and a great sense of gratitude to James for his generosity in sharing his cultural journey with me.

Upon returning to Australia, we began our foraging adventures by consulting botanical books before going on bush walks, with James also drawing on the traditional knowledge handed down through his family to inform our expeditions. As a child, James was introduced to a number of native foods by his Mother and Grandmother, and has fond memories of Kurdanyitpi Ruby Saltbush berries, Kurti Quandongs, Tainmunta Lysiana Species (‘Snottygobbles’) and Pakiyaka Native Currants.

- Patpawilya

- Kurti

- Karrkata

- Wadni

Our weekends became filled with bush walks across the Adelaide Hills and regional South Australia, with previously energetic hikes turning into stop-start bursts as we paused to scour hiking trails and scrubby reserves. We were slowly learning how to read the landscape through a different lens and now beginning to see the plethora of details that were always there, if only we had known where and how to look. Ever the amateur botanist, James frequently referred to pocket-sized field guides to Australian plants — not all of which were illustrated or offered adequate information to identify and confirm the edibility and traditional uses of the different specimens we found. One bush walk might necessitate the need to consult up to four different books for the information we needed before we would allow ourselves to sample new finds. But our efforts were almost always rewarded with an array of interesting treasures: sticky cardamom-flavoured Ngamingamina Slender Devil’s Twine berries; beautiful red, orange and yellow confetti-like handfuls of sweet Tilti Native Cherry; pink Native Raspberries and tart Pakiyaka Native Currants; fragrant Parnguta Chocolate Lilies with intriguing bitter-sweet tubers; mushroomy Native Plantain; Tantutiti Native Lilac for brewing sweet tea and delightfully delicate River Mint.

Summer adventures along the South Australian coastline into Ngarrindjeri country encouraged the careful and discerning surveying of coastal terrain for native foods. Our ubiquitous haul of Kuti Pipis (Goolwa Cockles), which will be familiar to many South Australians, took on a different meaning when placed in context with the coastal greens and other plants traditionally foraged and eaten by the Ngarrindjeri people. The scrub along the sand dunes boasted succulent Pirira Bower’s Spinach, sparkling Crystal Ice Plants, salty crisp Patpawilya Samphire, buttery Coastal Rosemary and lush Sea Parsley. The delightfully salty-sweet flavours of juicy pink Karrkala Multyu Pigface fruit, lemonade flavour of Coastal Bearded Heath berries, eucalyptus-apple flavours of Mantirri Muntries and purple salty-sweet Wadni Nitre Bush Berries quickly became favourites as we traversed the sandy dunes, rocky cliffs and scrubby landscape. From the ocean, we plucked vibrant salty treasures such as Golden Kelp, Sea Lettuce, Parraitya Crayweed, Neptune’s Necklace and numerous other seaweeds, munching the silky leaves on the beach and reserving some for later use in miso soup and Japanese-inspired dishes.

The natural progression from sampling raw plants, berries and seeds in the field was the desire to include native foods in cooked and prepared dishes in the home kitchen. While we thoroughly enjoyed the novelty of impromptu food experiences as part of walks and hikes, the desire to incorporate more foraged native foods in everyday cooking seemed like a step in the right direction in decolonising our kitchens. We focused on substituting native ingredients in dishes we already enjoyed making, thinking creatively about how to make new dishes that highlighted their flavours and textures in interesting ways.

Memorable dishes from this time include Wattle Seed tiramisu, Native Plantain and mushroom risotto, Kuti Pipi pasta, miso soup with Sea Lettuce, and Bower’s Spinach and eel pasta, the meat of which had been prepared in our own hand-built smoker made from mud, stones and a metal grate. With guidance from James’ Grandmother, we made our own version of the treasured Pakiyaka Native Currant jam to spread on toast and a matching compote for our porridge. Foraging near lush waterways allowed us to harvest Bullrushes, the fibrous yet succulent stems of which we oven baked in parcels with butter and herbs and ate with steamed trout and potato salad. With a bit of preparation, cooking in the field was also possible: I have fond memories of sitting on the beach with a portable gas cooker, flipping our Mara Murdumurdu (a wholegrain flatbread made from the flour of Ngurrku Spiky Headed Mat Rush and Tarnta Tatha Kangaroo Grass seeds) before filling them with a pan-fried, buttery medley of the day’s finds, which included Kuti Pipis, Patpawilya Samphire and Pirira Bower’s Spinach.

Not all our samplings of native foods have been a delight to our taste buds. Twiggy Daisy Bush boasted the lovely fragrance of rosemary and lemon and at first tasted deceptively sweet, followed by intense bitterness. I have a vivid memory of the pair of us sitting in a parked car on the side of the road in a national park, vigorously scrubbing our tongues with our jumper sleeves after experiencing the intensely sharp, bitter taste of Ngampa Yam Daisy. Though always keen to forage, sight and sample native foods, we didn’t always have the means to prepare certain plants in the field the way they ideally should be, especially during the fire ban season. Alas, Ngampa are much sweeter when cooked, though they will be mutually remembered for their terrible bitterness that day. There are also a significant number of wild foods that are toxic unless cooked and processed correctly — a warning that we took seriously and decided not to attempt for fear of poisoning — such as Bracken, Kangaroo Apple, Marti Bitter Bush and Kurdaki-Yuri Native Flax berries. Accidental poisonings can and do happen when foraging, so it is incredibly important to have knowledge and certainty about any wild foods that are ingested and to take appropriate precautions.

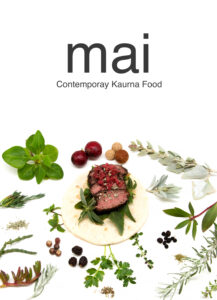

Our first year of foraging native foods and early experiments in compiling recipes laid the foundations for a number of significant projects and outcomes that James has completed in the years since. For example, the native garden he cultivated whilst living in Kamberri Canberra and different iterations of the Mai Contemporary Kaurna Food project, with select dishes of which have been presented at exhibitions and events since 2018. This project culminated in the 2022 digital publication of Mai Contemporary Kaurna Food (cover on left), a collection of fourteen recipes based on different geographical environments of the Kaurna Yarta Adelaide Plains. Through their ingredients, these carefully documented recipes vividly encapsulate a sense of place, but in light of our foraging experiences also capture moments in time — memories of long afternoons spent looking for treasures amongst fertile valleys, meandering tracks and scrubby sand dunes.

Our first year of foraging native foods and early experiments in compiling recipes laid the foundations for a number of significant projects and outcomes that James has completed in the years since. For example, the native garden he cultivated whilst living in Kamberri Canberra and different iterations of the Mai Contemporary Kaurna Food project, with select dishes of which have been presented at exhibitions and events since 2018. This project culminated in the 2022 digital publication of Mai Contemporary Kaurna Food (cover on left), a collection of fourteen recipes based on different geographical environments of the Kaurna Yarta Adelaide Plains. Through their ingredients, these carefully documented recipes vividly encapsulate a sense of place, but in light of our foraging experiences also capture moments in time — memories of long afternoons spent looking for treasures amongst fertile valleys, meandering tracks and scrubby sand dunes.

For a comprehensive overview of James’ native food foraging experiences and cooking adventures, and for updates on his recent work, please visit James’ Instagram page at the following link.

Afterword

There have been significant national leaps and bounds in the mainstream visibility and use of native foods since we first began our foraging adventures in 2016, including the publication of two exceptionally well-received cookbooks by Damien Coulthard and Rebecca Sullivan, Warndu Mai (Good Food) and First Nations Food Companion. It is exceptionally heartening that there is more widespread interest and awareness of native foods and traditional Aboriginal uses of native plants, and these moments of engagement are undoubtedly a step towards reconciliation with the ongoing effects of our nation’s traumatic colonial past. However, it must be acknowledged that in the face of burgeoning interest, there are numerous factors within the native foods industry that need to be discussed further, such as ensuring Aboriginal ownership of commercial ventures, increasing Aboriginal employment, protecting traditional knowledge, culture and intellectual property, and encouraging respectful foraging habits and protocols.

About Caitlin Eyre and James Tylor

James Tylor is a multidisciplinary visual artist, researcher, historian and writer who explores Australian cultural representations through the perspective of his multi-cultural Nunga, Māori and European Australian ancestry. He is currently undertaking a PhD through the University of South Australia in Tarntanya Adelaide on Kaurna Yarta. Follow @jamesptylor and visit www.jamestylor.com.

Caitlin Eyre is a freelance arts writer and the Curator and Exhibitions Manager at JamFactory in Tarntanya Adelaide on Kaurna Yarta. Her personal research interests are focused on mourning and sentimental jewellery (especially hairwork), folk crafts and women’s craft practices.