Kyoko Hashimoto and Guy Keulemans, Bioregional Rock Chain (Flinders Lofty Block – Adelaide), 2022, beach stones, oxide sterling silver, 40 x 220 x 220, Photo; Kyoko Hashimoto

Kyoko Hashimoto’s place-based jewellery practice makes visible the hidden substances that fuel economic growth.

(A message to the reader.)

As a creative practitioner, I use crafted objects to express environmental and sustainability concerns through the study of place-specific materials. Drawing from the work of Tasmanian ceramicist Ben Richardson, my method of place-based making potentialises a deep sense of connection to land, creating a link between manufactured objects and material origin. This framework guides my exploration of material capacities, relationships to place and the sensory experience of objects. The intimate qualities of the jewellery medium provide an embodied experience of wearing materials, as illustrated by my Coal Necklace (2020) and Bioregional Rock Necklace (2021), that feature locally foraged coal and stone spheres worn against the skin as a meditation on the finite nature of the earth’s resources.

Kyoko Hashimoto, Coal Necklace, 2020, coal, oxidised sterling silver, 20 x 120 x 150, photo; Fred Kroh

My more recent collaborative work stretches this traditional jewellery typology into the creation of larger objects. The Polylactic Acid Chain (2020), a collaboration with designers Guy Keulemans and Matt Harkness, uses polylactic acid polymer (PLA) waste from 3D printers discarded by makerspaces and re-imagines it into oversized neckpieces. While PLA is technically biogradable and recyclable, and is marketed as such, it is seldom biodegraded nor recycled in practice. Matt’s PhD research into PLA and the practices of makerspaces, corporations and government revealed there is no significant system in place to process PLA or even separate it from other plastics. Effectively, all PLA waste ends up in landfill. This exposes communications promoting PLA as an eco-friendly material as greenwashing.

Kyoko Hashimoto, Guy Keulemans and Matt Harkness, Polylactic Acid Chain (large necklace), 2020, PLA, 2173 x 939 x 110. Carine Thevenau.

Another project, Bauxite Mirrors (2020), a collaboration with Guy Keulemans, is a deep-dive into Australia’s aluminium industry that explores multiple facets of the unique metal. The project eventuated in the crafting of two aluminium mirrors that were displayed in the Sampling the Future exhibition at the National Gallery of Victoria in 2021. Below, I will discuss the journey of making these mirrors.

Aluminium is the most abundant metal in the earth’s crust, mostly in the form of bauxite ore. While this lightweight, corrosion-resistant metal is considered cheap and disposable today, when it was first discovered back in the mid-1800s, it was valued as more precious than gold. Today, aluminium has become ubiquitous, made into everything from drink cans and window frames to aeroplanes. However, there is a dark side to the industry. The original method for extracting aluminium from bauxite used a rare mineral called cryolite. The only significant reserve of cryolite was on the west coast of Greenland and, due to its importance in aluminium extraction, it is the only mineral on earth that has been mined to practical extinction. Furthermore, separating aluminium from its tightly bound compounds in bauxite is extremely energy intensive. Currently, energy used by aluminium processing plants accounts for approximately 10% of total energy use in Australia. Due to its high energy use, bauxite is often shipped to countries with cheaper energy such as China and India for processing and then brought back to Australia, increasing its carbon footprint. Australia has some of the largest deposits of bauxite ore and is the world’s largest exporter. Despite this, few Australians are aware of bauxite, its relationship to aluminium or its environmental impacts. We wanted to create an object that explored this link and its geological context by reframing it through concepts from Japanese Shinto that venerate natural phenomena.

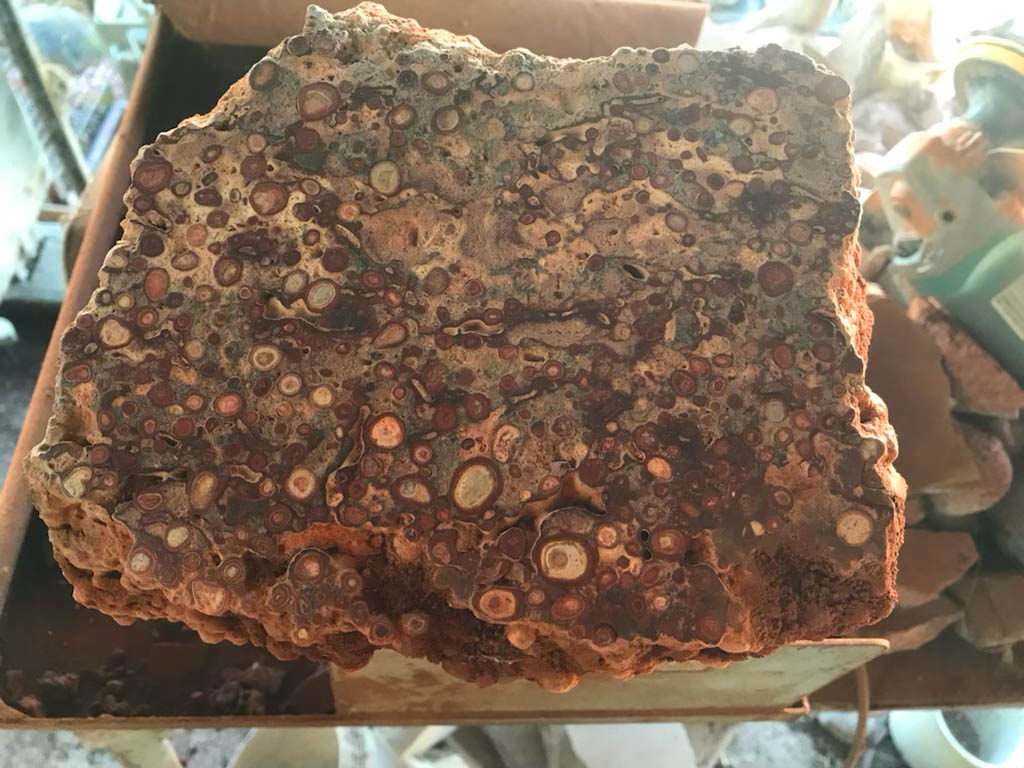

Attempting to purchase large pieces of bauxite proved to be difficult. We found small scientific specimens offered on sites like Ebay, but we wanted to work with larger stones. We used MinView, an open-access tool for tracking mining activities, to locate areas to forage for bauxite in the New England Tableland near Guyra. However, unlike gold, aluminium is almost always found as a composite in rock and, depending on the other constituent elements, they can differ greatly in appearance. The most common presentation is as a reddish brown rock with pisoliths, a collection of pebble-like stones bound within a clay matrix. We found several specimens that presented such characteristics, but were not sure if they were in fact bauxite without geological specimen analysis.

While we arranged for the rocks to be analysed, we managed to obtain bauxite indirectly from a mine in Weipa. Weipa is located at the northern tip of Queensland and has one of the world’s largest bauxite mines. We wanted to visit the bauxite mines ourselves, but this was prevented by the COVD19 pandemic. Instead, an ex-mine worker agreed to supply several large specimens of bauxite for the project. She even managed to send them by Australia Post, despite their hefty weight, due to their metallic content. The amount of metal extracted from bauxite rock is around 1:6, meaning it takes roughly 6 tonnes of bauxite to produce 1 tonne of aluminium. The visual contrast between the bauxite and aluminium, and this difference in weight and volume, was something we wanted to capture in the final design.

Aluminium has a fairly low melting point for metal, so initially we tried heat bonding aluminium to bauxite. We bought old aluminium window frames and alloy wheels from a tip. After chopping the aluminium into smaller size, we melted it within a simple homemade furnace using a gas lighter, steel cans and heat blocks. The molten aluminium was poured over bauxite pebbles to see how they would react. To our surprise, the pebble energetically resisted the molten aluminium and bounced away like popcorn. We then steered our thinking towards possibilities for cold-connection.

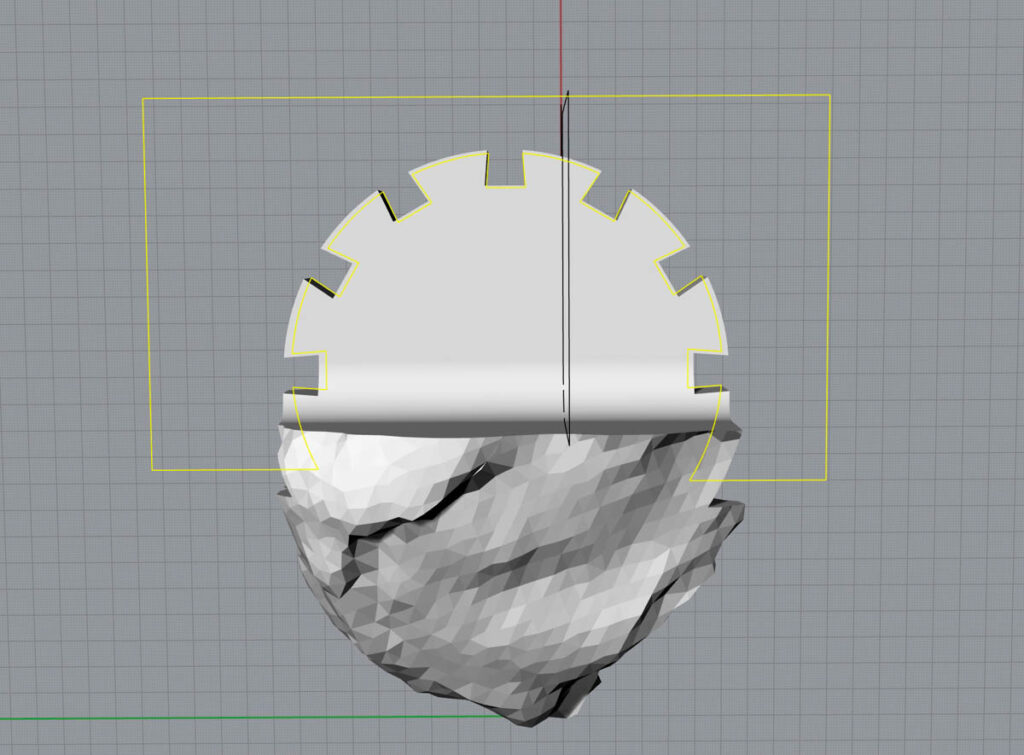

Back at the studio, Guy and I 3D scanned a piece of bauxite and designed a dove-tail for cold-connection with an aluminium sheet. We took bauxite samples to a stone mason for a water-jet cutting experiment. Unfortunately, this technique resulted in jagged broken edges, another setback. The pisolith structure of bauxite, its hard pebbles within a soft clay matrix, makes it difficult for blades and saws to cut the ore as they encounter different hardnesses. Bauxite is better cut with blunt saws at a very slow speed, constraining the ways we could shape the rock. Having gained a better understanding of bauxite and its limitations, we returned to the studio to develop new ideas for objects that show sensitivity to its natural characteristics, drawing influence from Shinto practices.

Shinto is a native animist religion of Japan. Rocks, trees, rivers, mountains, as well as animals, are revered as awe-inspiring natural phenomena. Today, Shinto in Japan is practised through various cultural festivals and rituals, and can be seen through craft and ornamentation. The shimenawa for instance is a decorative rope that is wrapped around significant trees as well as rocks to symbolise the presence of kami, a Shinto deity or spiritual essence. With its philosophy of sensitivity to nature, some aspects of Shinto are proposed to help change attitudes towards the environment. We considered that Shinto also has a tradition of making mirrors from metal and stone, dating back to the Yayoi period (300BC to 300AD), long before modern glass mirrors were invented. Some of these mirrors were considered to possess special powers.

Having worked with and learnt about bauxite, our designs reference the ancient Shinto mirrors. By working very cautiously with the stones, we wanted to honour the natural state of bauxite by making very little changes to its original form. The design required only two straight cuts; one to reveal the incredible internal complexity of bauxite pisoliths, and another to create a shallow groove to hold a sheet of hand-polished aluminium mirror. The weight of the metal mirrors reflects the 1:6 ratio, the amount of aluminium that could be extracted from each stone. The design allows the mirror to be removed, and if required, easily melted down for recycling.

Our simple design for the mirrors was partly due to technical limitations, but ultimately our desire was to honour the natural state of the stones while showcasing the incredible detail and complexity of bauxite; a geological phenomenon created in the earth’s crust over millions of years. In stark contrast, the polished aluminium mirrors held in place by the bauxite is highly processed as an industrial material. The mirrors reflect the world around us. Currently, there are around 746 million tonnes, or 80 kgs per person, of mined and manufactured aluminium available on earth. Given the high energy cost involved in aluminium smelting, as well as the ecological damage of mining, we ponder, if there really is a need to produce more aluminium from the mines.

Recycling aluminium on the other hand, only uses 5% of the total energy required to produce the metal from ore. This is just one of the incongruities of the aluminium manufacturing industry today. As makers of objects, we too use materials and resources of the earth. Investigating the material’s context, in manufacturing, use and geology, is an important aspect of what we do as critical designers. Through telling the story of aluminium in an object we hope to illuminate one extractivist paradigm of contemporary material culture and hopefully guide makers and industries to more sustainable practices.

Kyoko Hashimoto, Round and Square Aluminium and Bauxite Mirrors, 2021, aluminium, bauxite, 660 x 570 x 220 and 401 x 360 x 136., photo; Traianos Pakioufakis

About Kyoko Hashimoto

Kyoko Hashimoto is a Japanese-born contemporary jeweller based in Adelaide, South Australia. Working across critical design and body adornment, her project explores ethical and aesthetic challenges to paradigms of material practice in art, craft, design and industry. She creates objects that address existential threats posed by globalised resource extraction – particularly for those materials that dominate 21st-century existence: plastic, concrete and fossil fuels. Advocating for new kinds of sensory engagement with materials, Kyoko positions her work as tools to open up discussion around objects that transition between exhibition, commercial and domestic spaces in relation to ecology and the body. Her work is part of the permanent collection at National Gallery of Victoria, Toowoomba Regional Art Gallery and Art Gallery of South Australia. Kyoko is represented by Gallery Sally Dan-Cuthbert in Sydney.

Kyoko Hashimoto is a Japanese-born contemporary jeweller based in Adelaide, South Australia. Working across critical design and body adornment, her project explores ethical and aesthetic challenges to paradigms of material practice in art, craft, design and industry. She creates objects that address existential threats posed by globalised resource extraction – particularly for those materials that dominate 21st-century existence: plastic, concrete and fossil fuels. Advocating for new kinds of sensory engagement with materials, Kyoko positions her work as tools to open up discussion around objects that transition between exhibition, commercial and domestic spaces in relation to ecology and the body. Her work is part of the permanent collection at National Gallery of Victoria, Toowoomba Regional Art Gallery and Art Gallery of South Australia. Kyoko is represented by Gallery Sally Dan-Cuthbert in Sydney.