Laurie Paine draws a thread from Palestinian ancestors to a new life on the other side of the world, where she now mourns the tragedy in her homeland.

Laurie Paine translates the traditional designs of tatreez embroidery from Palestine into woven forms. These designs were absorbed from the many traditional embroideries surrounding her childhood home in Australia. For around 40 years, she has maintained a weaving practice, despite the relative lack of recognition. For her, weaving is the expression of her commitment to social justice, especially for those suffering in the war in Gaza.

I visited her studio in Hurstbridge. The 90-minute train ride from Melbourne wove through dense bushland, startling rabbits who darted into their burrows. Laurie lives with her husband and children on a rise overlooking rolling hills. Over tea, she begins her story with her grandfather, Gordon Boutagy, who had an electrical goods business in Jerusalem, selling His Master’s Voice. His wife, Laurie’s grandmother, raised four children in a middle-class Christian household. This was all upended in 1948.

✿

On 9 April 1948, a massacre took place in the village of Deir Yassin, as a warning to the Palestinians. Loudspeakers were saying that they were coming. My grandfather said, “You have to go. It’s very dangerous.” So my grandmother took her two younger children in the car across the desert to Egypt. They were shot at along the way. Luckily, they escaped with their lives. They took nothing but literally the clothes on their back.

My grandfather stayed behind with the other men and went to the Old City in an attempt to hold it against the invasion. But they had old rifles and were not trained. He was a lay preacher in the Anglican Church and a Boy Scout, so he was not a fighting man. They lost eventually, and my grandfather was captured by Zionists.

He was told, “You can stay here in prison, or you can go, but if you go, you have to sign here, and you can never come back.” Obviously, his wife and children were all in Egypt. So, what could he do? He signed the paper, and they then dumped him over the border into Lebanon. He was stuck in Lebanon for a year before getting to Egypt. It was impossible, and nobody had papers. They’d lost everything. When he finally got over to my grandmother and the family, he said, “If this is the way they’re going to treat us. Let’s go!”

My great-uncle, who had a hotel in Haifa, had already migrated to Australia and invited my grandfather. It was the white Australia policy at that time, so they couldn’t come as Arabs. They had to prove that they had some blood other than Arab. European relatives had to be found, or as my mother used to say, “European blood”. In the end, they were helped by the Anglican church to migrate to Australia.

They arrived in Sydney on Australia Day, 1950. My mother was 15 years old and eventually married a man from Queensland. Growing up in the 60s and 70s, I was conscious that I had a Palestinian family background, but it wasn’t spoken about outside the home. Nobody knew about Palestine.

The home was filled with cushions embroidered with Palestinian designs, and when my grandparents visited, they spoke Arabic.

At school, I loved art. A high school teacher got me started on making a tapestry using card weaving. This involves cardboard cards with four holes. You thread through the holes, then put a weft across, and turn the cards to create a pattern. It ended up in the Tops Arts exhibition.

I went overseas for a couple of years and shared a flat with a Ghanaian woman who was trained as a weaver. She had a little table loom set up and I played with it. I became interested in weaving, and I travelled to Ghana.

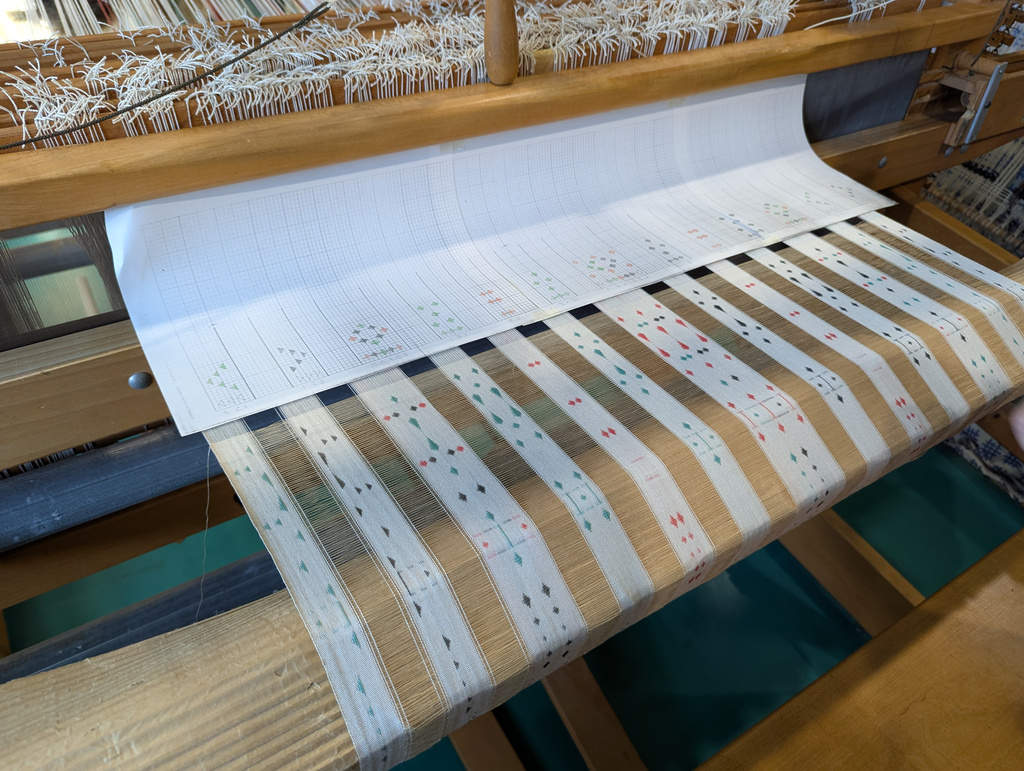

When I returned to Sydney, I enrolled in art school and studied graphics. A drawing teacher advised me to study at the Canberra Art School, which was taught along Bauhaus lines, with Udo Selbach as head of school. I chose the textile workshop with Michael Butler, who trained at the Royal College of Art. While there, I learnt all the different weaving structures, including twills, houndstooth, waffle, crepe, double cloth and piqué. We were encouraged to experiment with yarns and weave drafts. I discovered that I could make patterns, like little triangles.

- Laurie Paine, Untitled 1985, 143 x 93 cm

- Laurie Paine at opening of Discover Palestine Through Time at the Islamic Museum of Australia, 10 July – 5 October 2024.

While in art school, the curator Jeni Allenby saw my work and identified it as Palestinian. I hadn’t told anyone about my identity. She invited me to include my textiles in an exhibition of Palestinian artefacts at the Drill Hall Gallery.

After graduation, I travelled to Central America, including Cuba, Guatemala, and Nicaragua. We were interested in the Nicaraguan revolution. After that, I visited family in the Middle East, including Lebanon and Jordan. I crossed the Allenby Bridge from Amman to the West Bank to visit family in East Jerusalem. As my name was Laurie Paine, and I looked like a white Australian, there was no problem with my going across.

This was in 1986 at the birth of the Intifada movement. A student at Bir Zeit University had been killed by Israelis. I smuggled photos of his funeral back to Amman. While there, I couldn’t help but observe that my Palestinian relatives were treated as second-class citizens in their own country.

After returning to Australia, I worked with Elena Gallegos in Tasmania on banners for the Tasmanian Teachers Federation and the Electrical Trades Union.

With young children in tow, I then moved to Mittagong at Sturt when I got my dobby loom. Elizabeth Nagel was the master weaver at the time. That’s where I wove my black and white pieces.

I don’t have patterns. I just make them up. That’s something I learnt in Guatemala. I saw that the older geometric patterns had evolved into something more flowery. It’s a living thing. Of course, there will be standard patterns, such as those on the cushions around me. But it’s an evolving thing.

Recently, I wanted to do something in response to Gaza. I’d written letters to politicians. I’d tried to talk about it in demonstrations and with friends, but I felt like I was getting nowhere. Perhaps I could try communicating in a different format. So, I wove these as shrouds using the colours of the Palestinian flag.

About Laurie Paine