The manza xylophone of Azande chief Guga in Bondo, MO.0.0.14308, photo credit: Jo Van de Vyver © RMCA Tervuren

Adilia On-ying YIP writes about a Congolese xylophone that became a museum artefact in Belgium. She believes it should be returned and revived as a musical instrument.

(A message to the reader.)

This article will tell the story of the manza xylophone of Azande, a type of musical instrument that has been on the decline and rare according to reports in the 1930s. As part of the musical instrument collections of the Royal Museum for Central Africa, Tervuren (Belgium), the manza was owned by the customary chiefs, notables and court musicians who lived along the Uele River of the Congo Belge (the present-day northern region of the Democratic Republic of Congo). Being the symbol of authority and nobility, the manza was a rarity among the population due to its restricted ownership of the court and reserved for use in court ceremonies and enthronements.

Despite the decline of manza observed by the Belgian expeditors and ethnographers in the 1930s, a number of manza xylophones were first acquired by Armand Hutereau (1875-1914) for the museum collections during two expeditions in 1911-12 and expanded in the 1930s with the encouragement of Joseph Maes, the head of the ethnographical section of the museum. Since then, the instruments have become the silent witnesses of history and colonialism, and tell us the stories of politics, restitution, and cultural identity.

Manza is the endogenous name given to most fixed-key wooden xylophones of multiple calabashes with bridge boards that were found in various Azande areas along the Uele River, such as Bondo, Bili, Poko, Doruma, Bambesa, Likati, and Monga. To clarify, manza also refers to the ethnic group in the Central African Republic and a Ubangian language spoken by the Manja people. In the analysis of Olga Boone (1932), the museum xylophone collection has twenty-three instruments of this kind; however, it is not clear whether all of these xylophones were called manza, and used and owned by the court. The combination of voices and drums seems to vary according to the local customs of the court. The ethnographical record was scattered and absent.

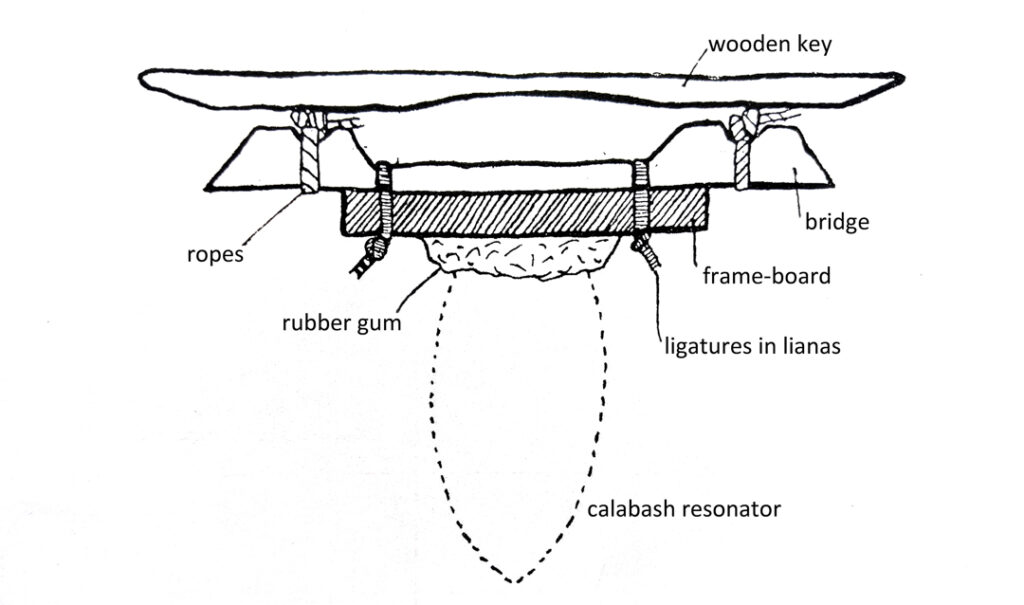

Among them, two manzas were owned by the Azande chief Guga in Bondo, lower Uele. They consist of ten keys, and the keyboard is mounted to the main frame board by a long rope and some small perpendicular bridge boards. The frame board has ten holes of 4 to 5 cm in diameter for holding the calabashes. They are the resonators of the keyboard and don’t create a mirliton effect as in many other xylophones in Africa. Different sizes of the calabashes are matched to the pitches of the keys. When the pitches are higher, the calabashes are smaller. The calabashes are glued to the frame board by resin or rubber and stabilized with some short sticks (straw or dried grass). For tuning the pitches, the wooden keys were shaved on the bottom side in the middle and were tapped at both ends. The keys were made of pterocarpus wood, most commonly traded as padouk (or padauk). Padouk is also commonly used in the production of Western xylophones and marimbas.

In the book Histoire des peuplades de l’Uele et de l’Ubangi (1922), Hutereau claimed that the musical instruments and objects were acquired through fair trade, quote: “Heads of clans and families enamoured with decorum had traded their ancient musical instruments – from which they coaxed only noise – for instruments imported from Europe. They needed mounts or carts, and the boldest opted for the bicycle”. The manza of Bondo were shipped to Belgium between 1912 to 1913, together with other collected items, including artefacts, musical instruments (xylophones, gongs, slit drums, membrane drums), phonographic cylinders and animals.

After an inventory number is assigned, the musical instrument was transformed into an artefact of the museum. The museum cabinets and depots have prevented them from destruction by wars, politics and insurgencies in their homeland, but these shelves and cabinets are also proof of the disruption of cultural heritage due to colonization. It appears that colonisation – including factors of Western acculturation by Christianity and modernisation – has accelerated the decline of manza and court music across Azande, and their functions and meanings were forgotten following the fall of its legitimate users, the customary chiefs. Under the control of colonizers, many chiefdoms were fragmented, and those who remained were forbidden to perform court music as it represented the chief’s political power. Permanent damage to the cultural heritage could not be reversed, even when such suppression died down and the colonial power was weakened.

The depot of xylophones and slit drums, Royal Museum for Central Africa, Tervuren (Belgium), photo by author.

Hence, the main question lies in how modern society can restitute the rightful meanings, but “the different same” to these instruments. Recognition and engagement with heritage and cultural objects can foster people’s pride and sense of identity, but we won’t be able to restore the former significance to the collections. While returning the collections to their homeland museums may seem like an appropriate action, it oversimplifies the complex meanings of musical instruments and cultural heritage that have been erased and fragmented by colonization.

Musical instruments were originally created for music-making and fulfilling social functions and roles, and should not simply be relocated to a museum for speculation by the public. This might only continue the legacy of the Western museums, and the instruments continue to be examined as the “others” of the long-gone customary society. Instead, in the decolonial era, restitution should focus on reconnecting them with the people who hold the cultural knowledge and practices that are imbued to them.

One approach could involve collaboration between ethnographical museums and communities. Through co-creation projects and art residencies, the museums could assist people to care for and recreate these instruments in the best way they can. A collaborative effort can help to restore forgotten instruments to their significance, reinfusing them with cultural meaning and connecting them to contemporary practices. As a result, musical instrument collections are transformed from mere objects of oblivion to agencies of remembrance, contributing to the construction and expression of cultural identity and spirituality.

About Adilia On-ying YIP

Adilia On-ying YIP is a post-doctoral researcher for the project “ReSoXy—Re-Sounding the Xylophone Collection from RMCA”, launched at the Royal Museum for Central Africa, Tervuren (Belgium) and the Royal Conservatoire Antwerp. As a marimba/percussion/balafon musician, Adilia’s passion for exploring different musical genres and cultures has led to exciting collaborations that cross the genres of classical, contemporary, world and popular music.

Adilia On-ying YIP is a post-doctoral researcher for the project “ReSoXy—Re-Sounding the Xylophone Collection from RMCA”, launched at the Royal Museum for Central Africa, Tervuren (Belgium) and the Royal Conservatoire Antwerp. As a marimba/percussion/balafon musician, Adilia’s passion for exploring different musical genres and cultures has led to exciting collaborations that cross the genres of classical, contemporary, world and popular music.