In mapping handmade creativity in the broader Asia Pacific, it is important that we go beyond the major cities. Village life is integral to much of the work that is emblematic of the region. In searching for the “story behind the things we make”, Garland now looks to the special places where authentic craft is produced, in particular the village. The online exhibition for Garland #6 features handmade works that have a special relationship to a village. This can be a remote village whose inhabitants pursue a traditional life, or a special community within a city where people work or life together. It can be a work made in collaboration between an urban designer/artist and village artisans. These works will celebrate the enduring contribution that village life makes to our creative world. This reflects a shared enjoyment in working collectively beyond individual gain. But it also gives us pause to think about the relationship between the city and the village. How might they coexist?

Fiona Wright | Susie Vickery | Srishti Verma | Sarngsan Na Soontorn | Nalda Searles | Nina Sabnani | Ujwala Pasla | Irfan Khatri | Bridget Kennedy | Louis Katz | Vankar Bhimji Kanji | Mavis Ganambarr | India Flint | Elaine Chan | Jade Brockley | Sandra Bowkett | Najwa Bdeir | Maggie Baxter | Penny Algar | Zuri Camille De Souza (Obataimu) | Nathan Beard

Chawandia village, Pushkar, Rajasthan – Fiona Wright

We use recycled silk saris and hand titch. Hand stitch is not traditional to our women, we have trained them.

http://the-stitching-project.com

Instagram: @the_stitching_project

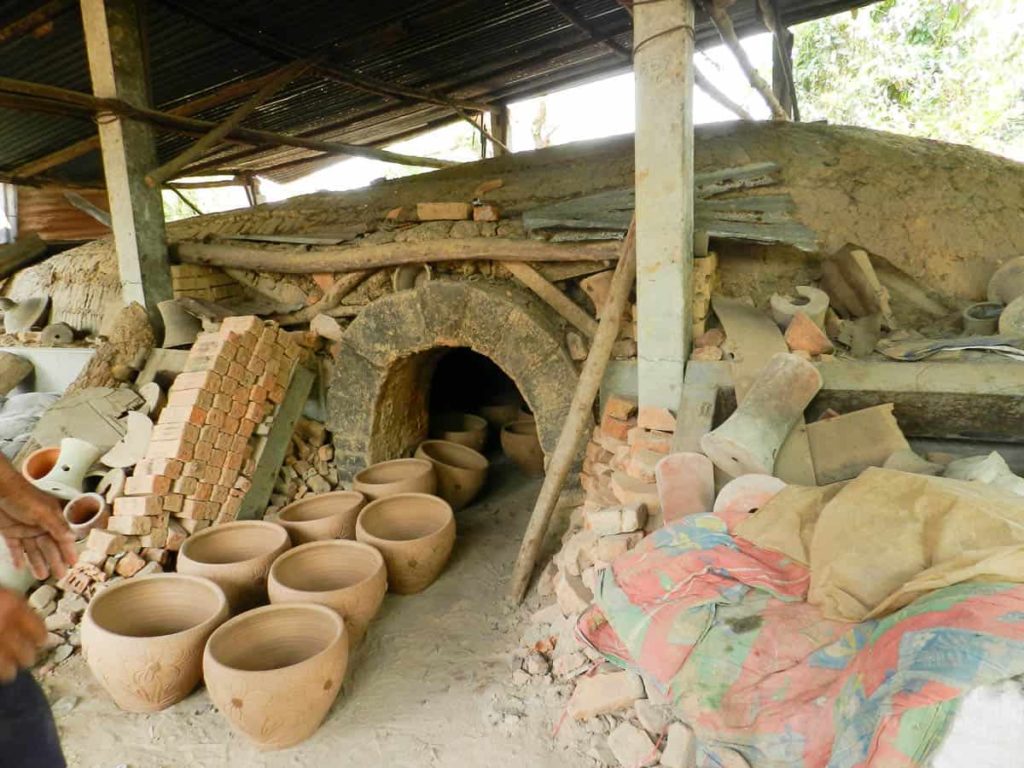

Kuwa, Danusha, Nepal – Susie Vickery

The centre is the Janakpur Women’s Development Centre and they paint, make ceramics, mirrors, sewing and screen printing. They have been going since 1989, after originally just painting on the walls of the houses, like in the photo in the village

Anjar, Kachchh – Srishti Verma

- Niraj Dave, Traditional pots, 2016, clay, brass, hemp rope, 16 x 8cm, photo: Srishti Verma

The piece is thrown and turned on a wheel using the region’s local clay. This is the traditional technique of Diwali clay toy making in the village of Anjar, Kachchh. Ramzu Ali Mamad Kumbhar, the master hand behind this piece, is a traditional potter from village of Khedoi and has a close acquaintance with Anjar and his brother potters in the village. This water jug is inspired from Anjario Karasiyo, a traditional water jug which was made by the potters of village Anjar to be widely used among the local communities of Kachchh. The jug was used to store and serve water. Niraj has made this jug with minimal changes keeping the form close to the original and its usage intact. There is a hemp coiling at the belly of the pot, which is again inspired from the roots of villages in Kachchh, where the locals used to braid their water carriers with hemp sacks in order to keep the water cool and avoid contact with the sun while travelling. In 2015, the traditional Anjario Karasiyo was displayed and auctioned as part of an event funded by Hermes Foundation. Dehaati, a fresh social enterprise between Niraj Dave, a ceramic designer and pottery craft enthusiast and Srishti Verma, a Designer and Researcher in Crafts, works on the values of local and rural.The word dehaati literally means “a villager”. Dehaati works on a range of products which are truthful, most original and local. The philosophy brings back the tradition of the purest material clay, traditional skills and revives the potters and pottery of the Kachchh region.

Instagram: @dehaatidesign

Sarngsan Na Soontorn

- Kong means hang. A coat rack made of teak wood from dismantled traditional old houses. The material is back to its structure life again, in a new scale, a new function.

- Nian means smooth and delicate, like a boiled then peeled egg. A form follows structure frame with a hand cut oval shape, this hanging mirror reminds an image of eggs in a bamboo basket hung upon a natural hot spring.

Jaoban, a word in our northern Thai dialect, means folks, villagers or ordinary people. It represents who we are and where we start from. Here in Chiang Mai, a town known for its distinctive culture and diverse craftmanship, we work with our resources and find inspirations in things around. From our scale, from our context, from where we are, we would love to share the world we see and the way we do with you.

A tree, Kalgoorlie – Nalda Searles

- Nalda Searles, Kangaroo couple made over a period of 10 years both in the landscape and in domestic studio, salvaged clothing covered with grass tree spathes, grass fibre heads and torsos, all hand stitched, 2009, lifesize, photo: George Karpathakis

- Nalda Searles, Hearth installation at bush camp in 2007, earth and stones with words

Over a period of ten years, this work was developed in the village of landscape and the village of metro outskirts in Western Australia, My village has long been a tree beneath which I may hold a class or make work of my own.

http://searlesartist.blogspot.com

Dhar, Kutch, Gujarat – Nina Sabnani

- Mehendi Khatri

- Ismail Khatri

- Bilal Khatri

Koyalagudem village, Nalgonda District, Telangana state – Ujwala Pasla

Double ikat silk dupatta Ikat is a tie-dye technique that uses great mathematical precision, immense patience and supreme skill to transfer intricate designs on to the yarn before they are woven together, resulting in an enchanting look of blurred edges in the finished designs. Rubber bindings are used to tie, dye, sort, rearrange on the yarn many times to reach the final design. In double ikat the resist dye technique is used on both weft and warp before interlacing them to form intricate yet well-composed patterns. The Telia Rumal is the one of the most complicated design in the double ikat category. The Telia Rumal has undergone a lot of evolution and in the present form it is a double ikat motif repeated many times all over the fabric.

Instagram: @Heritageweaves

Ajrakhpur, Kutch – Irfan Khatri

I was born in Dhamadka, Kutch, a drought prone, traditional region. My village was destroyed in the earthquake of 2001, and my family shifted to the newly established Ajrakhpur village. My family are traditional Ajrakh printers. I learned printing when I was fifteen. I have taken my work to exhibitions and shops all over India, and worked with National and international designers. As we reached wider markets, my community had the opportunity to travel and learn about markets. In 2004, I participated in a collaboration between artisans from India and Vietnam in Delhi. In 2006, I participated in the first class of Kala Raksha Vidhyalaya, , I began to access markets through the internet, and learned to use computer and mobile technology. By reaching new markets, my community has been able to build new, modern homes. In our village we are now introducing effluent treatment for the water we use in dyeing.After graduating I continued to grow and explore. I had the opportunity to participate in a show in UK. Active in the Australian-Indian Sangam Project network, I traveled to Indonesia. In 2013 I paired with Hariyaben for the Co- Creation Squared event in Mumbai.My current focus is on jali patterns of Islamic art. My Taj series has been very popular and become a new tradition. My other recent focus has been developing a distinctive range of sophisticated colours in natural dyes.I am member of the Governing Council of Somaiya Kala Vidya. Through the institute I have coordinated and taught a number of workshops on Ajrakh tradition

Sagada, Philippines – Bridget Kennedy

- Bridget Kennedy, untitled, 2016, local Sagada clay, 10cm x 35cm x 35cm, photo: Luke Torrevillas

- Sagada Philippines, hanging coffins

Every trip back to Sagada, Philippines, Luke and I visit Tessie and Seigrid from Sagada Pottery. We’ve been building up a small collection of their work over the years. During the last couple of trips, we’ve started making our own pots. These pots will be bisque fired and then left to await our return before we glaze them….It may be a year until our next visit but things work slowly in the mountains..and we know that they’ll be looked after. Originally this craft was introduced to Sagada by the son of an American missionary. The workshop is simple, made from local wooden logs, with dirt floors and unreliable electricity. The kilns are wood and gas fired. Sagada has now become famous for its pottery, with clay sourced from the local mountains, and all the glazes made in the workshop. Tessie and Seigrid don’t have a website or facebook page but can be contacted on +63 975 008 4800.

Instagram: @bkandco

Dan Kwian, Thailand – Louis Katz

- Unfired owls. The Owl is one of the standard forms in Dankwian

- Drying owls awaiting firing.

- Fired owls with woodash surface

- Pottery awaiting loading in the wood kiln.

- Unloading soaked clay, background wood pile

- Pakama village life: farmer walking to the fields

- Eucalyptus Firewood delivery in a Thai made Farm Truck called a Rot Iten

- Eucalyptus firewood. The heavier parts of the wood are used for paper pulp.

- Danwkian Green Grocer in the village

I was introduced to Dan Kwian village with some images shared by a fellow ceramics student. A few years later I was introduced to a potter from the village and I ended up spending almost a year living there. I return frequently. Dan Kwian ด่านเกวียน is a village in Nakorn Ratchasima Province in Northeast Thailand. The potters in Dan Kwian have been making utilitarian pottery, mostly water jars, basins, and mortars at least since 1740 CE. Dan Kwian is located near a source of beautiful clay, and is on an important historic trade route making it a convenient place for a pottery. Its name means toll station or stopping place for ox carts. Since the early 1970’s, as use for water jars has decreased, the village has been diversifying its ceramic production moving into more decorative ceramic items, including tile, carved murals, jewellery, and carved decorative pottery. Because of its playful diversity its been called a “ceramic Disney Land”.By 1980 the village was planting trees as fuel and as a cash crop and the village still mostly fires with wood kilns. The wood is mostly eucalyptus snags and tops, parts of the trees impractical to ship or turn into lumber or pulp. Historically much of the ware was fired to high, stoneware temperatures of about 1225˚C. This temperature is high enough to get a light glazed surface from the wood ash and resulted in a natural looking dark brown surface.In the 1970’s the village employed perhaps 20 people in pottery making, now, including other handicrafts the village crafts are supporting thousands. Historically pottery in Dan Kwian was made by rice farmers during the dry and hot seasons. The historic kilns were dug into clay rich soil near termite mounds and would be submerged during the long wet rice season from June until December.

Sali, Kutch, Gujarat – Vankar Bhimji Kanji

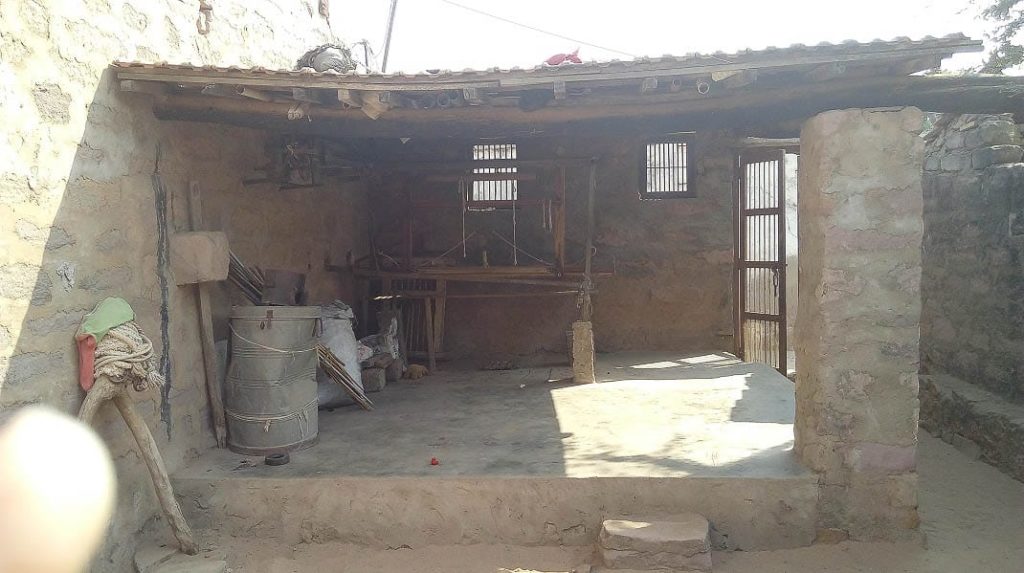

My traditional art is artistic weaving (Kutchi weaving) of Kutch district. I’m from the village, Sarli of Gujarat, India, which is the village of traditional weaver’s community named Vankar (Meghwal). I belong to a family of traditional weaving artists, and inherited this tradition from my forefathers. The weaving techniques, designs, and motifs survived and evolved through ages. I learnt the craft of weaving from the joint efforts of my father and my mother which is mostly imparted through informal interactions and hand on training. As my father was serving in bhimani khadi bhandar which is in Mandvi, Kutch, for 35 years. He had lots of experience which he passed on to me while giving me training in weaving. While I was studying in school, I started to work with my father and my elder brother by helping them in my free hours at very young age. Now, I have been doing this work since last 20 years. I have studied up to first year BA In collage. But I left my further studies to join my traditional craft because of my poor family condition. And I also decided to take the tradition of my forefathers to a very new level by developing some new designs and yarns. I have enormous love for my craft and decided to take it on a higher platform.

In 1997, I started traditional weaving on my own. This time was the biggest challenge and change in my life. I understood the concepts, design elements and principals, colours, presentations, theme etc. I also met many designers and eminent personalities of the craft and design sector during these years of weaving. I developed a strong sense of traditional aesthetics, motifs and design. I made my collection on the theme “traditional with contemporary”. I’ve also introduced the use of semi pashmina yarn, for the first time ever in Kutchi weaving. Traditional artistic heritage—this is our traditional art which my ancestors say our family has been doing for the past 100 to 150 years. In ancient India, the work system was distributed as per the different communities. Our community was specialized in weaving clothes. Then we started weaving dhablas, and then shawls, stoles and mufflers came into existence slowly and gradually. Now all shawls and stoles are commonly used by many people winters to the cold seasons and make a fashion statement. And in future too people will keep using traditional art for historical art heritage and keeping and some fashion using.

Elcho Island – Mavis Ganambarr

Here and (t)here, India Flint

My village is a most remarkable one, having no fixed address and a fluid population. It is a village nonetheless, mostly composed of women, not because it is exclusive but because that’s who it seems to attract. It is one in which the inhabitants care for each other and for the earth, and are committed to paying attention to all that is beautiful in this whirled. In our village (which forms organically whenever and wherever) we gather to observe and respond to the poetics of place) we write poetry, draw, stitch and gather leaves for dyeing. We break bread together and spend convivial evenings making stone soup…a rich and nourishing vegetarian composition formed from whatever plant-based foods the participants bring, cooked together in a cauldron along with my travelling soupstone. We take long walks and sometimes there is singing. We stitch aprons and bags, create poetic journey cloths and fold exquisite dyed paper books. But the most important product of my village is the enduring friendships that are forged there, between people from wildly different walks of life, between the young and the older, the experienced and those bravely taking their first steps. Welcome to my village.

Long Lamam, Sarawak, Malaysia – Elaine Chan

- Long Lamam artisans, Penan baskets, 2015, rattan, largest basket 40cm x 28cm x 20cm, photo Elaine Chan

- Long Lamam artisans, Long Lamam village, 2015, photo Elaine Chan

These are traditional Penan baskets made from split rattan that has been twined and plaited by villagers in Long Lamam, Sarawak, Malaysian Borneo. Colours are natural, black from burying in mud or coloured using food colouring. Long Lamam is a remote village—not connected by roads, or telephony communication. To get there from the closest city, Miri, one must either travel six hours on road by 4WD or fly by twin otter plane for 1 hour and travel on road by 4WD for 1.5 hours, and travel by river on narrow boats for another hour. The village has approximately 250 inhabitants from the Penan tribe, who traditionally live in close affinity to the rainforest. The organisation I work in, Barefoot Mercy, came across these plaited arts of the community when we were there working on a project to support the provision of pre-school education to the community. The pre-school is the only education facility in the community, where many have not received formal education and illiteracy rates are high. These days rattan as a material is gradually being replaced by other materials such as plastic straps due to the increasing difficulty of obtaining rattan and the work required to prepare rattan into strips to be used for weaving. We are not in the crafts business, but we immediately recognised the beauty and the quality of these crafts and now assist in the sale of these items in our home city of Kuching, Sarawak. Upon our return to our home city of Kuching in Sarawak, some of the baskets were also converted to a more contemporary look. A canvas lining was applied and the straps converted from the traditional backpack style straps to a slingbag. One of these baskets (the smallest one in front) was submitted to and won an award of excellence for handicrafts from the World Crafts Council Asia-Pacific in 2016. They have also been featured in fashion shows by Edric Ong, an award-winning Malaysian designer. We hope this award and exposure will be a boost to the community currently navigating its way through change (surrounding deforestation impacts on their traditional way of life) and an affirmation that their traditional arts are valued and not to be forgotten.

Uluveo (Maskelyn) Island, Vanuatu – Jade Brockley

- Assorted Maskelynes fans, 2017, pandanus, coconut leaf spine, approximate dimensions 35 x 25 x 0.5cm, photo: Jade Brockley

- Lutes, Vanuatu

- Women of Uluveo island

Woven crafts of Vanuatu are utilised by almost everybody in daily life. Most women will have learned to weave mats, which are important objects for exchange in ceremony and ritual, as well as used within and around the home. Many of the 83 islands of Vanuatu produce special craft techniques and designs that are then linked to a particular place. A basket from Lelepa is made using a tightly coiled method; a mat from Pentecost is coloured using a distinctive reddish-purple dye obtained from the root of a particular tree. Located in the southeast corner of Vanuatu’s Malekula, the Maskelynes are an isolated group of small islands accessible only by boat. Surrounded by mangroves, some of the islands are uninhabited, and none have vehicles. Transport around and between the islands and the mainland is by canoe, banana boat or foot. As with other rural areas of Vanuatu, diet consists predominantly of root crops and tropical fruits. Being surrounded by water means fishing is also a large part of daily life. The island of Uluveo (also called Maskelyn) has a population of approximately 1000 people, and houses three main villages: Pellongk, Lutes and Peskarus.

Women from the Maskelynes are renowned for weaving a particularly decorative style of fan, which is instantly recognisable and highly revered across the archipelago for its intricate patterning and design. Jenny and Edlyn operate the Maskelynes Women’s Resource Centre, which hosts training and workshops for women to help provide opportunities for improving livelihoods. These include sewing, weaving, and sessions for women with disabilities. There is also a small handicraft centre that sells various locally woven crafts. There are fifteen women on the island of Uluveo who have the knowledge and skills to weave the Maskelynes fan. Eight live in the village of Peskarus, where Jenny, a renowned weaver and village leader of women, and Nisel (in blue) are two such women. Women learn to weave from their mothers, aunties, sisters, friends. Weaving is done at home, and it is often a communal affair—a chance to get together for kakae (food) and storian (chat). Those who want to learn how to make the Maskelynes fan will spend a full day in training to learn the various and complicated steps involved. The fan is woven using two local materials—dried pandanus, and the rigid spines of young coconut leaves. Weaving one will take a full day; but before the weaving begins, the materials must be prepared, and this takes a full week. Jenny explains the process of material preparation: “You must choose the yellow leaves on top of the coconut tree, as they are soft and won’t break during weaving. The coconut trees are very tall, so you must first find a pikinini (child) who will climb up and cut the leaves down for you! The stik brum (the rigid spine of these large leaves, also used to make stick brooms) of each leaf is removed; the stik brum must be boiled for cleaning, and then dried in the sun for two days.” Pandanus leaves must be cut, boiled and sun-dried. The drying process takes a full week. Fans can be woven “white” (no added dye) or dried pandanus leaves are coloured with bright commercial powder dyes. Jenny uses 36-40 spines for each fan. They must all be the same length and girth. The spines are tied together twice, which forms the basis of the handle. The untied parts of the spines are folded outwards on either side; this forms the fan’s main structure. A complicated series of folds and criss-cross weaving “locks” the splayed spines in place. Once the main structure of the fan is created, pandanus is woven in to create rigidity, shape and pattern. Edlyn weaves beautiful mats but does not weave the Maskelynes fan. However, she works with the others by preparing the pandanus leaves. There are many steps to weaving the Maskelynes fan, and there can be up to four women who have contributed to producing a single fan. Perhaps one woman will provide some prepared dried pandanus; maybe another woman will colour it. Fans are in high demand even just within the small island of Uluveo, and payment will go directly to the weaver, who may then share some of her payment with those who have contributed. In this way, the women of Uluveo work together to share their skills and rewards; they also help to create and promote the valuable roles of women in cultural society by providing a village identity through their craft.

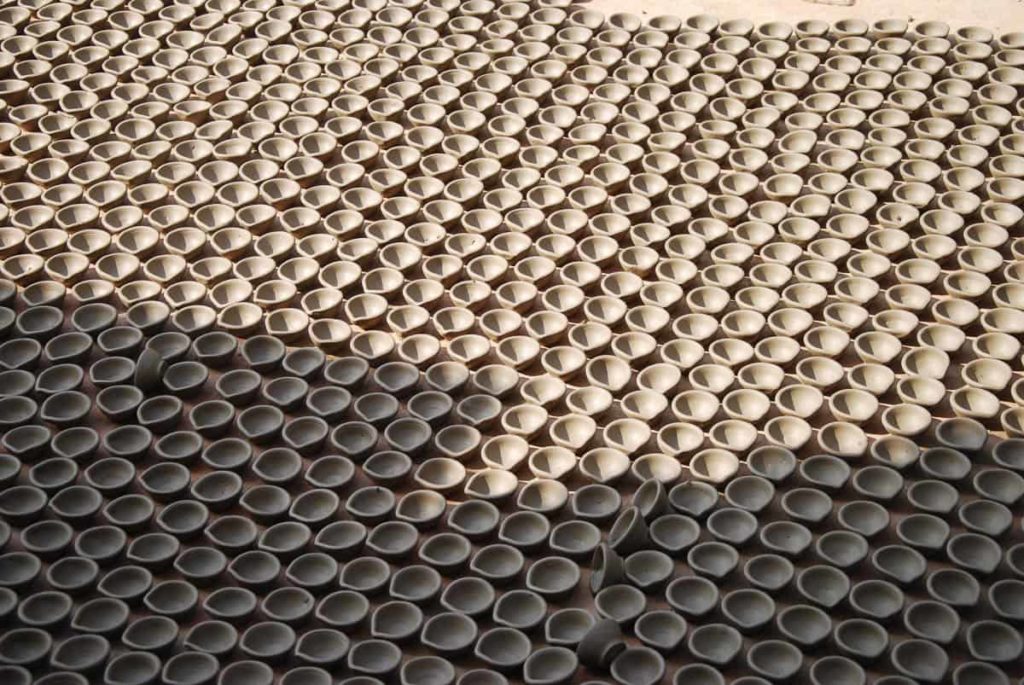

Kumhaargram, Delhi – Sandra Bowkett

- Poppi Prajapat & Anju Devi, Massed Diya, 2016, clay, 2cmx3cm

These diya are made by a husband and wife team, he throws “of the hump” on a wheel and she cuts and places. Leading up to Diwali throughout the village you will see husband wife, father son, father daughter, friends, neighbour teams producing 1000s of these diya for the local market.

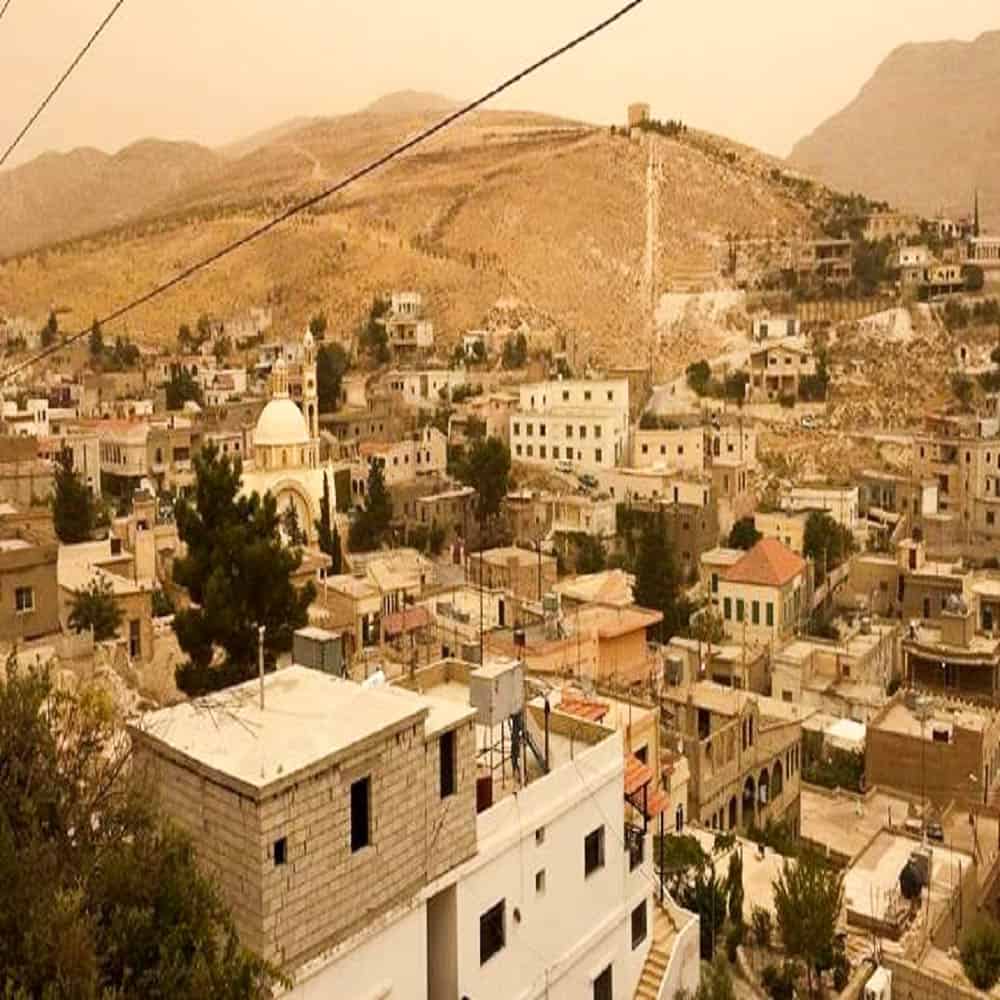

Fakiha, Lebanon – Najwa Bdeir

- Nahla Soukarye, alboxe, 1985, sheep wool, 3 x 5m, photo: Nahla Soukarye

- Fakiha village, Lebanon

The “Fakiha” village is located about 127 km to the north east of Beirut, in Mohafaza Baalbeck-Hermel. It is surrounded by agricultural villages where we find a huge number of cattle. The handmade carpets, dated 300 years ago, are what makes “Fakiha” one of the most famous villages in Lebanon. However, few families are still weaving carpets, using 100 year old equipment, due to the hard competition coming from the industrial carpets that are manufactured in large factories. The pure sheep wool forms the main raw material in the production process which is divided as follows: washing wool, sweeping wool, spinning wool, dyeing wool in natural colors. It’s important to note that a 4 x 3 metre carpet needs around six months to be produced. The distinctive wool and its long fur are the main features of the high quality of these handmade carpets, which are one of the most famous carpets in the world.

Instagram: @nahla

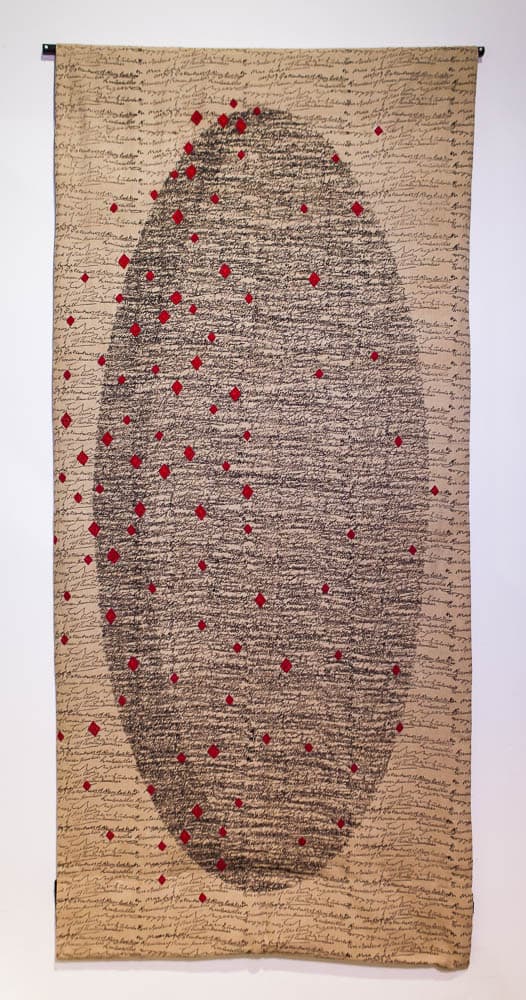

Bhujodi (weaving) Ajrakhpur (blockprinting) and Zura (embroidery), Kutch, Gujarat – Maggie Baxter

- Maggie Baxter. Here and There series. 2004. Hand woven cotton, resist print with mineral iron dye, Pakko hand embroidery using rayon thread. 2004. Photographer of the artwork: Robert Frith Acorn Studio.

- Zura Village village, photo: Neela Kapadia

- Maggie Baxter. Poetics of Nothing series ( 1 of 3). Direct block printing using organic iron dye on handwoven cotton with Ahir hand embroidery .250cm x 112cm. 2016. Photographer: Atul Dube

- Salimbhai Khatri blockprinting workshop, Photo: Maggie Baxter

This work is now quite old, but I chose it because, although the outcome is contemporary blocks and layouts of my own design, it uses traditional techniques (hand weaving, resist block printing, and hand embroidery) that are specific to three separate villages in Kutch, Gujarat, India.

The image of the block printing workshop is of Salimbhai Khatri, who printed the Poetics of Nothing series in Dhamadka, Kutch, Gujarat. Here he is looking at another work in progress (2016), just printed. This work is one of a series of three in which text is purposely used to convert no meaning. It is printed with a block of my own design, using an organic dye made from iron filings. The floating diamonds were embroidered by women from the Ahir community, once nomadic herders but now settled in Kutch.

Euroa, Victoria – Penny Algar

- Tamara Potter, Grade 5, Euroa Primary School, Painting on paper for Fungi Festival, 2016, 60 X40cm, photo: Mister & Lady Photography

- Aurora Smith, Grade 5, Euroa Primary School. Artwork for Wild Strathbogie Festival 2014. Polystyrene Print. 40 X 25 cm, photo: Mister & Lady Photography

- Euroa Post Office, 2017, photo: Kate Auty

The artworks were made in the classroom of art teacher and artist Pauline Fraser at Euroa Primary School. Both the Wild Strathbogie and Fungi Festivals were collaborative community engagement events initiated by the local Strathbogie environmental group, the SRCMN (Strathbogie Ranges Conservation Management Network). Artist and SRCMN committee member Penny Algar and Pauline Fraser discussed how the children might engage with the project conceptually through art. Pauline is a very highly skilled artist and teacher as is evident in the technical proficiency and exuberant expressiveness in the children’s artwork. All artworks were exhibited publicly in Euroa to much acclaim by the local community. Both Festivals also comprised other events and workshops for the wider community.

http://www.euroa.ps.vic.edu.au/

Tyrchiang, Meghalaya – Zuri Camille de Souza (Obataimu)

Transforming their bodies into pottery wheels — unlike traditional pottery that uses a spinning wheel — the women orbit the pieces of clay, forming them with their hands, moulding them into vessels through a series of gestures resembling a dance performance.The clay evolves into organic, smooth forms that come out of the interaction between palms, fingers and earth. Made throughout the year in the village of Tyrchiang — located in the Sung Valley of Meghalaya—each piece of black clay tableware is formed out of a special, highly-technical knowledge that requires a deep understanding of the materiality of black clay as well as of one’s own body. These skills are passed on from women to their daughters and today, it is deeply embedded within the cultural fabric of this community. The practice is inherently sustainable—the pottery is fired over coals twice a month with firewood collected by the community and shared communally.

Obataimu collaborated with Dak-Ti, a design collective in Meghalaya, to curate an exclusive range of tableware made by these women. The restorative minerals, infused within the black clay of the vessels, make cooking, storing and eating a therapeutic practice. Black clay can withstand very high temperatures and requires only a mild detergent whilst washing. Each piece is handmade, and we embrace the subtle differences in colour and form that make them unique. The products age naturally and develop their colour over time.

Thai spirit house – Nathan Beard

The video Hiraeth was exhibited at 4A Centre for Contemporary Art in 2015 as part of the exhibition Future Archaeology, curated by Toby Chapman. The work takes found Super 8 footage taken by my Australian aunt when she visited my mother’s home province of Nakhon Nayok for the first time shortly after my parents’ wedding. In the process of documenting the projection of this film the projector malfunctioned and jammed, burning a hole in the original footage. The resulting video combines a digital transfer of this film, the filmed recording of its destruction, and footage I shot myself when revisiting my mother’s province in 2013/14 with a digital SLR. When I found out about the original Super 8 footage I was really intrigued by my aunt’s Western touristic gaze, and I thought it was interesting how this aligned with my own documentation of the landscape around my mother’s home decades later with completely different recording technology. I wanted to highlight similarities in the way we processed the allure of this foreign landscape through the different mediums, and examine how our perspectives overlapped. When I went to Nakhon Nayok in 2014 it was the first time I had been there in nearly 20 years, but I felt a palpable and emotional connection to the region. This complex negotiation of estrangement and familiarity definitely informed the editing of this video.

When I arrived at my mother’s former home in Nakhon Nayok in 2013, it had been unoccupied for close to two decades after the death of my maternal grandmother. My mother’s brother Prajoub lived next door to this abandoned property and also helped to build it, acting as a caretaker while my mother and aunt were living in Australia. In 2013 Prajoub was diagnosed with terminal cancer and it was because of these health concerns that my mother returned to this former home. The spirit house in this photograph was documented at the back of this property, after having fallen off of its plinth. With my mother I was able to create a series of works in this abandoned home, titled Obitus, focusing on this homecoming. Using low-fi interventions such as smoke machines and dry ice I wanted to create sequences of haunting imagery that alluded to the passing of decades, evocative of the weight of encountering memories contained within this family home. In particular the use of smoke as a visual motif was directly inspired by several things, including the smoke from incense burned as offerings at domestic shrines, as well as the morning mist which would raise from the hills in the distance that were visible from my mother’s village, and plumes of cremation smoke from funeral pyres at nearby temples. See video here.

Nathan Beard (b.1987) is Perth-based interdisciplinary artist who works across mediums including photography, video and sculpture. His practice is primarily concerned with the influences of culture, memory and biography, in particular through the prism of his Thai-Australian heritage. Beard’s work often includes intimate and sincere engagements with family to poignantly explore the complex ways a sense of heritage and identity is negotiated.

Comments

What a global village we have all developed.. Its wonderful and gives me great heart to continue under the trees.. Thank you Garland.