1.

To say that beauty is all around in Kyoto is undeniable, and daily life here provides constant reminders that refined hand-making is still central to this place. Percolating within the fast-constructed architecture of the modern city are countless fonts of beauty arising from time spent in making, concentration accorded by makers and attentiveness applied by discerning appreciators who are more than just “consumers ” (as we shall clarify presently). The work of hands is on show everywhere in The Old Capital. A single plump mochi sweet, a glistening block of perfect tofu emerging from the flow of water at the local tofu shop, a humble ikebana in a train station display case, a rough tea bowl nursed during the taking of tea and wagashi at a temple, the soft glow of a lacquer box in the window of a revered maker’s atelier—each of these unadorned things changes the rhythm of walking through the town. You linger, you say sumimasen to passersby as you pause in your stride, altering your course slightly. This thing deserves your attentiveness. Here is one more object in Kyoto that strikes you as more beautifully made, by hand, than it strictly needs to be if utility was the primary concern. And so you divagate through town, from thing to thing; so many things still crafted by hand, very often by the people standing right in front of you.

2.

The bamboo master of Sanjo-dori

- Traditional bamboo shop in Kyoto on Sanjodori near Higashioji-dori; photo: Prettyshake

At the foothills of the eastern mountains, one such day of divagation brought us up short at the doorway of a bamboo master craftsman in a nondescript shop on Sanjo-dori. The master, who must have been in his eighties then, held a single length of bamboo in one hand and one of the largest, sharpest knives we’d ever seen in the other. He was bent over, as many older Japanese craftspeople are, by years of working down at tatami-level and by the lack of calcium during wartime. And yet he brought this knife down in the course of a single breath with keen power and control from above his head down to the tatami in one unhesitant stroke. A fine long sliver of bamboo materialised from the gesture. He was cutting towards himself. It was thrilling to watch this dangerous moment of meditation-making.

Above us hung a gathering of bamboo baskets for ikebana. Tiny tags held prices with many zeros at the end, way beyond our means. He and his family had been the makers of ikebana baskets for the imperial family for many generations, he related to us, his daughter translating. He pointed above the baskets, to the lengths of bamboo stored in the rafters over our heads, gesturing to “10 years old”, “20 years old”, and then “older’. To get the pliability required to shape one of those intricate bamboo baskets, a 20 year curing period was preferable, he explained, as if that was a perfectly reasonable lead-time. So, yes, time spent in making, attention paid by a maker, but also the inherited time imbued within the object by the years of learning and the years required by the maturing materials: all these simultaneous, slow cycles of time animate the object.

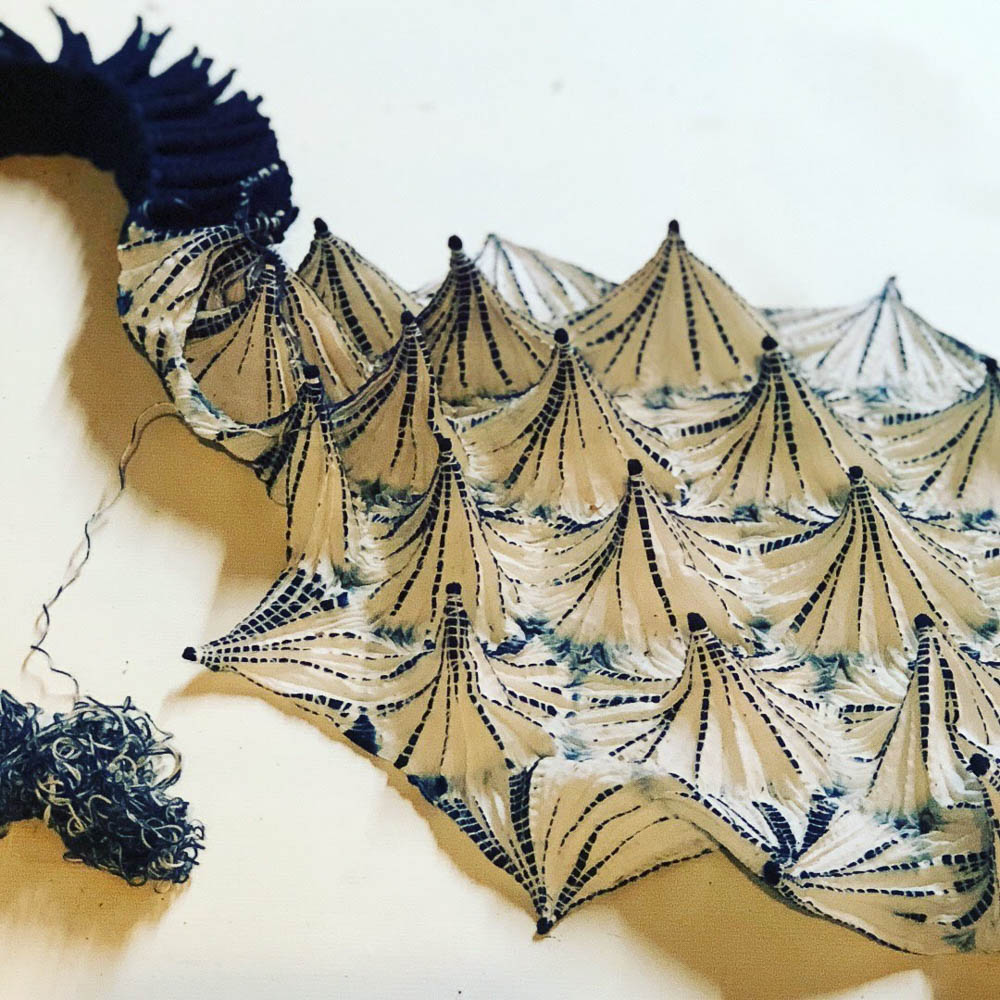

Years later, we remember this encounter while conversing with Eloise Rapp, textile maker, textile scholar, current resident of Kyoto. Eloise describes the shift in thinking about the value of things that comes when you consider that the crafted item you’re living with is impregnated with all of this TIME. Accumulated time, not just the time that it took to make this particular item, which was itself often long, painstaking and sometimes even pain-full. Consider the scarred hands and nails of women who have for decades tied cloth for shibori dyeing, winding lengths of fine string deftly and with considerable force around innumerable tiny peaks in the cloth before dyeing. Or consider the unexpected toxicity of some traditional craft materials. The young master-maker Mio Heki specialises in kintsugi, the “art of precious scars” which is deployed to repair and celebrate the continuous existence of broken objects. On working with urushi, the sap used to make the pliable lacquer with which she re-makes an object, she says:

During my first year working with urushi, my arms were covered in bubbly blisters and rashes due to allergic reactions. I even had to seek help at the hospital and take medicine to relieve the pain. Nowadays my skin handles it better but it can still get red and itchy if I accidentally happen to touch the lacquer. (Lisa Nilsson, Mio Heki: Kintsugi Artist and Urushi Master, Kyoto Journal, August 28, 2018).

Working with risky materials adds a degree of time and care, of course. Then keep in mind the two weeks that the urushi takes to cure and harden. And before that is the time and care Heki-San takes in making each of her tools, the fine brushes fashioned from single rat hairs, the tiny spatulas of bamboo. None of this can be read in the final crafted object unless you look for the time inherent to the object. Unless you make that shift that Rapp describes, that reconfiguring of the ideas around the value of things. The painstaking practices involved in the crafting of objects in Kyoto asks of us that we maintain the role not of consumers so much as custodians or caretakers, that we embrace mottainai, the Japanese injunction against wastefulness. As we shall see presently, this injunction sits paradoxically, uneasily and as an abiding challenge amidst the plainly profligate consumption of contemporary Japan. The craft-traditions have a pointed, political role to play within this drama of ecological and economical sustainability and profit-harvesting.

Back in the bamboo master’s shop we are reminded of the tension between these handmade crafts holding so much accumulated time and value beyond monetary calculation, on the one hand, and the world of handicrafts, cheap and small objects on the other. Small handicraft souvenirs made in fabrics with Japanese motifs are all around us in the bamboo master’s shop; tissue-covers for slipping into a handbag, small zippered purses, chopsticks nestled in cloth slipcovers. Nicely made, with the aura of “craftiness”, but they could very well have been made in bulk in Vietnam, or Indonesia.

They’re here out of necessity, a way to lure in tourists walking back to the city from the must-see temples clustered in the Higashiyama and Okazaki areas, a means to draw passersby inside so that the encounter with deeper time and different values might become possible. The need to sell the trinkets pushes paradoxically against the ancient craft-keeping that is the real, preferred purpose of the shop. But this is how it is now, explains the daughter, who nudges us toward an awareness of the crisis that is quietly on display, as the old man’s profound knowledge and exquisite, embodied dexterity are poised to pass into oblivion.

This kōgei craft master is lucky, in that his daughter has stayed with him so that he can continue to work for as long as he is able, but he has no successor and the generations-long bamboo studio will die with him. In this atelier, as in so many others in this city, after centuries of family-keeping, the profit-margins of globalised manufacture, the shifts in Japanese family-structures and the altered expectations of young people are all combining to put the old modes of slow, inter-generational training and making at dire risk.

3.

“We have no screens here.”

Who has the money to buy exquisite Kyoto kōgei craftworks any more, who has time to make them? And where will they be made? On each return to Kyoto, everywhere you look one more small-scale workshop has dematerialised. In its place is another 8-spot parking lot. It mystifies visitors that there are few protection orders on old buildings in Kyoto, or at least few that can apparently escape the stranglehold of the yakuza over real estate in certain parts of this city. Kyoto’s treasure chest of aesthetic riches in the form of its traditional architecture is forever being drawn upon, and not replenished.

Even if individuals are prepared to invest in the renovation of Japanese traditional architecture, Japanese wooden carpentry itself is a specialist craft in crisis, with fewer and fewer carpenters apprenticed in traditional woodwork. And even with will and with money, access to the store of traditional materials is dependent upon having the right connections and introductions, approaching in the right way, with the right language, entering an elaborate network of obligations and permissions that is centuries-old. A foreigner we know, renovating a Japanese wooden house, finally tracked down a storehouse of old wooden sliding screens. Money in hand, prepared to pay full price, he watched as the trader stood in front of screens stacked back as far as he could see and insisted “we have no screens here”. The newcomer was not part of the subtle but extremely rigid system of obligations and deference that governs how traders and buyers interact here. The trader would rather sell no screens than sell without the proper introductions and protocols. Kyoto is a truly mysterious mix of open and closed, and both tendencies impact upon the present and future of craft in the city.

It’s always the openness that will strike you first in Kyoto. The fact that crafted objects in the city go hand in hand with delightful encounters with their makers and vendors, and these encounters are, for the most part, unhurried and thoughtful. Despite faulty Japanese and hesitant English, no transaction with a Kyoto craftsperson goes without a conversation about the object. Often the acquisition of the object comes with an extensive ritual, of sitting, even taking tea, presentation, wrapping, handing over. None of this can be rushed.

4.

The Kyoto “down-shift”

- Kiyomizo pottery shop and garden; photo: Prettyshake

One of our most cherished encounters with the world of traditional craft in Kyoto came when we learned that a friend had commissioned the making of some mystery objects as an anniversary present. The gift giving came with a ritual of presentation and maker-meeting.

Most meanderers of the steep narrow streets wending up to the mighty Kiyomizu temple in Kyoto’s eastern mountains encounter the close-packed consumerism on these old-pilgrim paths and see only a tourist trap. But the legendary Kiyomizuyaki ceramics that have been made in small workshops off these roads still exist amidst the shrines to Totoro and the airbnbs and the matcha soft serve joints.

Our dear friend and maker Yuko Sugie lead us off a path thronged with temple-trudgers and into a hushed green courtyard. After a greeting with tea and other impeccable courtesies, the vendor then glided off past the shelves glowing with gold-glazed Kiyomizuyaki and returned with our box and an array of photographs. Opening the box and putting down in front of us two cups, she gestured from the cups to the photographs. The photographs show a scene around a table with people holding the same cups as the ones that sit before us; they are stills from a film by the great Yasujiro Ozu, made in the 1950s. Ozu controlled all elements of the mise-en-scene in his film, right down to the tableware. These cups were designed by him and made by this very Kyoto ceramics studio, and they are still made by them to order 60 years later. Our friend, knowing that Ozu was one of our favourite directors, commissioned them to be made for us, engaging a continuity of time that animates craft and life in Kyoto.

When you arrive in Kyoto the first critical shift is to down-shift into a different pace of moving through the city. Everything happens slower here and with more attentiveness. This is a walking city and, for now, it’s still possible to map the city via the purveyors and makers of traditional crafts. Ceramics, certainly; there are days of studied exploration ahead with the ceramics of the Kiyomizuyaki and Kyoyaki districts. Lured by exquisite Japanese paper? There’s a magnificent afternoon of wandering to be had, starting at Morita Washi, south of Shijo, then wending north along the covered Teramachi shotengai to the nexus of paper shops where Teramachi-dori meets Nijo-dori. Drift back south-west from there to Rakushikan, at the ground floor of The Museum of Kyoto, where, as a local guide says, “Here, the conversation between people and paper takes place everyday.” Spend any time with the astonishing range of papers on offer and you begin to grasp that this conversation is happening in a rare dialect where aesthetics and utility are melded. Indeed, you discover that the names for the different kinds of Japanese paper that you can see and handle here are usage-centric. For example:

haku-uchi-shi (for making gold foil)

haku-ai-shi (for mixture gold foil)

katagami-genshi (ornamental stencil paper for kimono)

maniaishi (for folding screens)

kabe-gami (wall paper)

kinkarakawa-shi (paper with the texture of tanned leather)

shoji-gami (for sliding screens)

fusuma-gami (for sliding door)

shoga-yo-shi (for paintings and calligraphy)

kosode-bunko-yoshi (for wrapping kimono)

hosho-shi (writing paper)

senka-shi (for paper bags)

chochin-gami (for paper lantern)

kasa-gami (for umbrellas)

ningyo-shi (for dolls)

shikishi (for poetry writing)

senmenshi (for folding fans)

Usage-based naming is only one of the ways to classify the extremely refined products of the tesuki washi (handmade paper) craft tradition. The Rakushikan catalogue of washi is as head-spinning in its detail as the catalogue for Tanakanoa Senryoten, Kyoto’s stunning natural dyeing emporium.

Handmade Japanese paper can be classified in several different ways:

(1) according to the materials used, (2) the district in which it is produced, (3) the decorative techniques involved, and (4) the purpose for which it will be used. [Rakushikan]

Both bamboo and paper sit within the rarified world of the most prized of Kyoto crafts and the Rakushikan list of ways to classify paper mirrors the criteria that a kōgei crafted object must fulfil. Materials, place, techniques, purpose. All of these factors are crucial.

In order for a piece to be officially recognized as a traditional Japanese Handicraft, it must meet all five of these requirements.

- The item must be practical enough for everyday use.

- The item must be predominantly handmade

- The item must be crafted using traditional techniques.

- The item must be crafted using traditional materials.

- The item must be crafted in its place of origin

As a way into the cluster of revered traditional Kyoto crafted objects that meet of all of these criteria—containing within them centuries of transmitted expertise in handmaking—we’ve compiled a youtube playlist of videos showing Kyoto kōgei crafters at their meticulous labours. It can be found at.

The signature high-crafts of Kyoto read like an endangered species list. The list includes, but is not limited to:

Kyo-takekōgei/Kyoto bamboo crafts

Kyo-shikki/Kyoto laquerware

Kyo-sensu/Folding fans

Kyo-ningyo/Kyoto dolls

Kinzokukougei/Kyoto metal crafts

Kyo-kanaami/Kyoto metal weaving

Nishijin-ori/Woven textiles from the Nishijin district of Kyoto

Kyoyaki and Kiyomizuyaki/ceramics from two specific areas of Kyoto

These are the crafts that have been refined and imparted through generations of embodied knowledge held by families and formalized master/assistant relationships. And so it follows that they are approaching the same transmission crises as the Sanjo-dori bamboo master. They are the high crafts, set apart from the much more openly accessible instruction system governing the handicrafts overseen by the government-endorsed Japanese Handicrafts Instructors Association.

Established in the 1960s, the 12,000 plus instructors of the national Association maintain quality control over eight Western-style craft forms via workshops, instructor training courses and exhibitions: knitting, embroidery, lace-making, quilting, painting, hand weaving, home sewing, calligraphy, leather craft, pressed flowers. Looking deeper into their formalised instruction systems, you find that the forms of those craft traditions being taught are relentlessly Western. All the Japanese versions of those craft methods are absent in the curricula. Embroidery but not sashiko, patchwork but not boro, weaving but not kasuri, calligraphy but not shodo, dried flowers but not ikebana. These endemic Japanese craft traditions are falling outside of this overarching and regulated system of instruction. From what we can tell, they are being conveyed piecemeal via private classes and workshops, person-to-person tutelage, Instagram-inspiration and online instruction.

Venturing into the more exclusive world of the old high-craft traditions, the means by which these specialist stills are being kept alive are even more opaque. An attempt was made to create a new market for a choice selection of products from a few of the generations-old Kyoto crafting traditions with the inception of “Japan Handmade” in 2013, though this venture appears to have waned. Heralding the creation of this informal guild at the time—and noting the “depressing trajectory ” of the great Kyoto craft traditions—Hugo Macdonald wrote:

The word “craftsmanship” is doing very well. It has become the trump card for any marketing campaign seeking to sell a brand’s story as one with integrity, skill and provenance. But poor old “craft” has been left behind, languishing in gift shops, unloved save for the odd great aunt or eager tourist. Where does traditional craft fit into contemporary life? It’s a problem felt the world over. It’s felt more keenly in Kyoto though, home to one of the world’s greater concentrations of traditional crafts and craftsmen. Even in Japan, a country where craft is revered to deific proportions, domestic demand both to learn and buy is waning. The preservationist approach that kept skills and techniques alive for centuries is now the biggest spanner in the works; modernising one’s heritage craft to chase a new market is akin to sacrilege. [The Hand Made Tale – Kyoto. Monocle, Issue 61, March 2013, pp 132-135]

5.

Searching for craft in Chion-ji

All of these issues are encapsulated in that encounter at the bamboo master’s studio-shop, with the $2000 ikebana baskets hanging above and the $8 handicrafts right at buy-level. If you hold the image in your mind and then go out to enjoy Kyoto’s markets, the intricacy and delicacy of the situation can be discerned with even more nuance. Chion-ji is a good place to start a craft-quest; a quest not just to pick up an object or two but also to gather a fuller understanding of the “eco-system” of craft—high, low and in-between—that sustains and is sustained by Kyoto commerce and culture.

Chion-ji Temple is located across the road from Kyoto University, at a junction connecting the eastern mountains to the central merchant districts and the Imperial Palace that verges on the edge of the riverine lowlands further west. On the fifteenth day of every month, artisans, providores and shoppers of all ages converge on Chion-ji to enjoy the celebrated craft market. The tourist quotient is considerable, but mainly this market serves Kyoto citizens.

Chants and music drift from the cool dark of elevated temple halls. At ground-level, food is available. Because this is Kyoto, amidst the pickle stalls and miso and umeboshi plum vendors there are breads and pastries everywhere, as good as any you could get in a Paris market, and coffee, prepared slowly and meticulously in the pour-over style. Homegrown vegetable stands nestle against small sideshow stalls where deft and patient kids scoop goldfish with nets that are designed to dissolve soon after contact with water if the first or second scoop fails to reap a prize. The pot plants that enliven every back-street Kyoto perambulation are for sale here in huge numbers and varieties. Really though, the people converge for the handicrafts.

In the same way that the shoppers at Chion-ji are a generational cross-section of Kyoto citizens, so the vendors comprise a microcosm of the Old Capital’s artisanal interests and standards. Most noticeable are the hobbyist stallholders all over Chion-ji, a great many of them offering knitted creatures, arigumi-ed creatures, felted creatures, creatures carved from wood and moulded in papier-mache and shaped out of clay. It’s Japan, and an inanimate object that can be made into a creature will be made into a creature, whether by a crafter or by a product designer (try buying a kitchen sponge in a department store that hasn’t been fashioned into some kind of animal form). The creatures on offer here in all materials are delightful and excellently made, but it must be said that very few are deeply weird or unsettling or category-busting. It has become a haphazard quest, conducted over many years of returning to this market, to rummage out the weird within the vast expanse of crafted stuff. We have returned with some idiosyncratic treasures that continue to delight. The clay otter-ish creature pictured here is gloriously odd, and it was nestled within a ramshackle menagerie of equally askew animals arrayed around the base of a tree by a fellow from way out of town. On a later visit, we found a young Japanese man who deployed a breezy free-form embroidery-sketching to coax these vivacious vegetable creatures into life. Many years earlier, a young illustrator searched for English words to describe the creature she had drawn. “Watermelon”, she finally pronounced, to our puzzlement. Then, making clawed hands and momentarily baring her teeth she clarified: “scary watermelon”. In each instance, the delightful encounter with the maker has accrued to the object and has become part of what we cherish in our collection of odd market finds.

Generally though, this is a market in which you can find any kind of handmade bag or purse or book cover or bottle cover or tissue cover, as well as a great many handmade clothes, all made in a variation of a set of “on trend” patterned cottons. Almost without exception, these items are fashioned out of new fabric from the apparently endless array on offer in huge emporiums like Nomura Tailor on Shijo-dori, which propel a handmaker economy that persists even as mass-production behemoths such as Uniqlo dominate national mercantilism.

While these artefacts attest to a dedication to hand-making, it must be said that they are not especially founded or invested in local traditions. Nor are they much concerned with mottainai. The vast Kyoto flea markets, Kobo-san and Tenjin-san burst with tables struggling under the weight of exquisite kimonos available for as little as 500 yen each, many of them products of the Kyoto kōgei tradition, with exquisite yuzen patterning, shibori dyeing, silk embroidery. Yet very little of that old fabric ends up repurposed here, given new lives in crafted items. The ever-present niggle of dread that accompanies a visitor to Japan—a friend identified it perfectly as landfill fear—follows you into the market.

It won’t surprise anyone who has been to the printed diary section of the Kyoto’s Loft department store, which takes up a third of the stationery floor, that Japanese consumption is driven by having an endless (and endlessly unsustainable) array of choices at hand. In the handicraft market as in the department store, it’s hard not to be overwhelmed by the material implications of so many variations, so much stuff, so little re-use. Furthermore, the aesthetic at this level—beautiful as it is—is not keyed toward innovation or the fine-tuned delectations of local materials or technical proficiency or sustainability. The old systems of skills and knowledge transmission aren’t much in evidence either. Given the young age of many of the stallholders, their skills are much more likely to have come from YouTube or the miles of craft books in any bookstore than from sitting at the feet of an expert. Noticeably too, the breathtaking expertise embodied by the atelier-based bamboo-master is hard to detect amidst the hurly-burly of the popular market.

But mingled amidst the cheerful hobbyist stalls at Chion-ji, there are several highly-skilled artisans who have been trained in more specialist modes using materials and techniques that set their wares apart from the demotic array. A master sweet-maker offers hand-fashioned chestnut mochi (sticky rice sweet dumplings) that are as good and long-term memorable as any you could find in the ancient parlours revered downtown. Young couturiers sell elegant linen garments that they have very likely designed, cut, layered and sewn in their lounge-rooms. There are ceramicists, glass-blowers, fabric-dyers, toy-makers, weavers of linen and hemp. All these serious practitioners make artefacts that their buyers want to treasure and pass on to loved ones over extended tracts of time.

The point is: Chion-ji shows a large portion of the filamented system of old knowledge-keeping, workshopped pedagogy and personal vendor-to-customer feedback-relations that abide still in the appreciation and daily use of hand-made artefacts in Kyoto. This appreciation of objects that have been suffused with hand-plied labour and long durations of use—often inter-generational durations—abides even amidst the “churny”, high-turnover consumerism that also characterises contemporary Japan. There is a kind of educational and ethical eco-system on show within the temple walls at Chion-ji. Artisans with varying degrees of expertise and ambition inform and challenge each other, providing a kind of glossary of taste and quality that is shrewdly appreciated by a discerning and demanding clientele. Amidst all these transactions, buyers learn and apply comparative, evaluative rigours which in turn set standards for the makers’ productions.

What’s more, Chion-ji market itself is part of a larger system of maker-fairs distributed across the city. There is the other beloved handicraft temple market occurring on the last Sunday of every month at Kamigamo Shrine where, amidst the shoppers cooling their feet in the stream that runs through the centre of the market, we found, memorably, Akira Kaida, a young potter offering celadon vessels that respect but also adroitly adapt and evolve the great traditions of Kyoto greenware fabrication.

Returning to the markets to see him eight years after the purchase of these cups, we explained that we drink coffee from them every morning and they give us an immense amount of daily pleasure. Kaida-san came out from behind his stall, held his hand to his heart and said “this is why I do what I do”, and he bowed until we were out of sight.

6.

Use as much skill as possible to produce something useful

Kōgei is generally understood as a category of hand-crafted objects, expertly made, sold by the maker in the area in which they were made, and demonstrating the highest standards of their craft. We prefer the more active description of kōgei ventured by the wonderful indigo artist Chiharu Ohgomori at a talk she gave at the Japan Foundation in Sydney as part of the exhibition The Intuitive Thread. With the caveat that kōgei was more commonly used in relation to ceramics than her field of textiles and natural dyes, she said that in her understanding the essence of kōgei is “to use as much skill as possible to produce something that can be used every day.” There is no more apt description of the form and the spirit of the celadon vessels purchased at the Kamigamo market.

At the market this year we entered into two new maker relationships that we similarly hope to revisit in years to come. One was a man who crafted local Kyoto bird species out of wood in miniature, carefully painting them in colours matched exactly to the picture in the Kyoto bird guide he opens for your edification when you select one, pointing back and forth and making sure you register the name in English and Japanese. The other was with three stallholders selling miniature hand-blown glass vases. The vendors were the maker and his two kids, aged perhaps five and three. The five-year-old silently demonstrated their use: you put a single flower in them like this. Obediently, we now put a single flower in ours each day.

These two main monthly Kyoto craft markets bracket the legendary Kyoto temple markets, Kobo-san and Tenjin-san, held on the 21st and 25th of every month at Toji and Kitano-Tenmangu temples respectively. Admittedly these massed gatherings are mainly flea markets peddling collectibles and antiques, but craftspeople also ply contemporary wares amidst all this history. Indeed the history—splayed all around in used-kimono stalls, old lacquerware, cast iron and bamboo vendor-stands—provides a vivid context for the new wares, for many different styles and standards of production are displayed. The wisdom of the ancients is on show, venerated and persistent, exhibiting centuries of techniques, materials and decorative modes in an ordinary, everyday manner, for all the passing world to see, scattered along the dusty temple lanes and around the crowded shrine-grounds and pagoda platforms.

Placing all this aesthetic “market-pedagogy” within the larger context of the great city of Kyoto, you start to understand how tradition, communal courtesy and inter-generational cultural inheritance are stitched into everyday life here. Kyoto, of course, is millennially the capital of Japanese culture, politics, spirituality and philosophy. A site of learning and discerning, an obligatory pilgrimage-destination for all Japanese people, the city deploys its cultural treasures, its museum-collections and annual festivals and massed rituals as a robust, popular system of knowledge-keeping, standard-setting and teaching and learning.

Moreover, within an hour’s train ride of the grand Kyoto Rail Station, there are more than a dozen universities, including several splendid creative arts and design colleges where the old techniques and thinking-modes of paper-making, painting, kilning, garden-design, fabric-weaving and dyeing are maintained. This means the town throngs with bright young people who routinely converse and jostle with the stringent “older garde” of Kyoto merchants and artisans whilst also messing with the hugger-mugger of throwaway culture. As a result the “everything more beautiful than it needs to be” is evident everywhere from flyer design to the pot-plant gardens spilling into the street outside every second house to the arrangement of lunch on your plate.

Once, we watched a construction crew wrestle old tatami mats from a building, drop them in an open-bed truck and proceed to arrange them in such a neat and pleasing fashion that it became a stunning everyday display of visual intelligence. The aesthetic values and design principles that govern everything in the town are constantly evaluated, enforced and sometimes adapted in quotidian rituals and environments. Thus deep tradition is ordinary, everywhere and everybody’s, even as it is austerely policed by an ever-ascending hierarchy of dilettantes, experts and venerated masters who exert their influence in guilds, production studios, boutiques and teaching circles. Just how much this system encourages innovation over the obeisance to normative strictness is a fraught question. But it certainly means that, even as the transmission of knowledge to the next generation is faltering, there are still a plethora of exemplary products and processes on display in Kyoto.

7.

Slow and fast in Kansai

Furthermore, wrapping around the city of Kyoto is the region of Kansai, which is arguably the most energetic and paradoxical of the national regions. The quickest way to explain this is to note that Kansai happily embraces two polarised ethic-worlds: the vast tumult of Osaka with its prodigious energy and appetites, with its deal-making bluster and rowdy BBQ bars and shouty stand-up beer-halls, at one extreme, and Kyoto with its shadowy quiet, its aesthetic precision and cool tinkling coffee shops and scented temples, at the other. In Kansai, the full range of tastes, aesthetic criteria and experiences plus the complete benefit of their synthesis are obvious to all. Exclusive, slightly aloof and discerning but also inclusive, energetic and eager for negotiation: all these factors combined make the Kansai way.

Which means that, generally speaking, slow and fast cultures agitate and activate each other in Kansai. Indeed, here and elsewhere in Japan, companies have done an excellent job of packaging the look and feel of LOHAS (Lifestyles of Health and Sustainability, pronounced rohasu) and “slow life” (suroh-raifu) and sold it back to people as fashion. With the economies of scale as they are, it’s safe to say that these garments were certainly not produced under “slow life” conditions. Muji have sold a bajillion incense burners and “girls in the forest” flowy dresses with Lohas marketing, and on the material level, it can be hard to discern at a glance the crucial difference between an oversized linen dress from Muji and a handmade oversized linen dress designed and made by a stallholder at Chionji market.

The slow/fast dichotomy is also a treasure/discard dichotomy, for if the main lesson of sustainability is to consume less, then the old Kyoto craft traditions—which encourage spending more on one excellently made object that will last forever, priced at a level that allows the maker to live and keep making—have much to teach us. Appropriately paradoxical, the craft culture and its modes of memory-keeping and teaching are both formal and informal, insofar as Kyoto itself is an extensive tutorial in patterning and handiwork, available for browsing and idea-grabbing even as it is also governed by the customary behaviours and fine gradations of authority and deference that suffuse all social relations and decision-making in Kyoto.

8.

The living archive

Throughout the town, while old timber houses get demolished and electronically augmented commerce blares from newly built department stores, tradition remains installed in establishments that have occupied the same premises for a few hundred years or more: brush and ink specialists, dyers, paper boutiques, suppliers of ikebana vases and kenzan, needle shops, incense emporia, and the list goes on. Quiet teaching-sites for anyone wandering in off the streets—usually experienced artisans and mature home-studio practitioners—such places are staffed by knowledgeable vendors who keep the traditions while waiting for the customer to earn some good counsel from them. By contrast and complement, the markets allow neophytes and trainee makers an opportunity to offer their variations on the age-old orthodoxies. The experimenters and innovators can find their place amidst this world of judgement.

Most strikingly, over the past couple of decades, with anxiety about succession-planning amplifying among the guilds and the families that have always purveyed their craft-knowledge from generation to generation, a few kōgei masters are welcoming outsiders into the workshops, occasionally offering advice for free, occasionally permitting the newcomers to spend time in workshops, usually as observers but occasionally as assistants. While these small moves towards different modes of skills-transmission cannot replace the long apprentice-training that steeps craft mastery into the nervous systems and manual dexterity of acolytes (think of the bamboo-master’s rarefied-yet-physical skills) the granting of wider access does push back against oblivion. Think of it as an informal “seed-bank” program for specialist skills.

For example, there’s the traditional weaving and dyeing atelier Ohara Koubou, located in a mountainous temple-district one hour north from central Kyoto. The koubou offers “experience classes” for novices and sometimes they permit researchers and neophyte artisans to attach themselves to the studio’s work-regimes. The outsiders might be young local people not sure yet whether they are prepared to devote themselves; or they might be foreigners coming respectfully to learn but not able to promise the decades of vassalage that used to be the necessary commitment with an apprenticeship.

One such outsider is the aforementioned Eloise Rapp, the Australian designer and self-described “practice-based researcher” specialising in textiles, fashion, community-development and sustainability whose essay can be enjoyed in this issue of Garland. Through her work with the Sydney social enterprise The Social Outfit and elsewhere, she is accustomed to seeking out craft knowledge that is held in stories and workshop experiments and rituals rather than in printed handbooks or ratified trade certificates; and she is keen to emphasise the companionship and soul-strengthening sodality that arise when craftspeople commit to collaborate over extended periods of time.

An example of such a venture is the natural dye (or kusakizome) tutorials that Rapp joined and documented during 2017 – 18 at Ohara Koubou, where she learned of the local leaf, bark and root extracts and the fixatives and metal-salt mordants needed to invest objects and textiles with the distinctively Japanese colour palette that cannot really be generated industrially but can still be drawn forth from the old, foraging ways. Here she saw not only into the profound “eggplant blue” of Japanese indigo-craft, but also the thrilling reds of madder rose root dyes as well as the metallic greys and tans that can be conjured in mordant-steeps and fixative-tubs (see Rapp’s blog post).

The ramifications of the masters granting such generous access to traditional craft-knowledge are unpredictable but thrilling. For example, a couple of Rapp’s friends who accompanied her on the Ohara workshops took their portions of knowledge back to Osaka and Melbourne, respectively, where the lessons learnt enter the swirl of influences and can be primed for implementation in heuristic and sometimes innovative ways, away from their exact point of origin. The next year, over coffee, the Osaka friend informally provided points of entry into the world of Japanese textiles to another Australian maker, Suzanne Hauser, relating not only the basics of natural dyeing practiced in the koubou but also certain decorative fabric-strengthening sashiko stitch-techniques that derive partly from Japanese clothes-mending culture (which can be understood as morally and aesthetically related to kintsugi practices). Hauser, who was already adept at costume-sewing for theatre, then took her understanding of these methods back to Sydney where they were overlaid on her extant skills to produce an evolving style of self-taught experimental sashiko, garment re-fashioning and natural dyeing with local plants.

Thus through everyday use plus informal but respectful instruction in the technical fundamentals, followed by the heuristic adventures of muddling through, the crafts retain a resilience and foster a distributed “living archive” whereby the benefits of continuing techniques far outweigh any anxiety about inexpert mistakes or wonder-guided innovations.

9.

Everyday treasures

As is often the way with enduring fabrication techniques in Japan, the aesthetics and the pragmatics tangle benignly and deeply. A few everyday treasures from Rapp’s market-fossicking give these ideas material form. In her breezy Kyoto house, she uses a huge old mosquito-net. As she shook it out for us to examine we mistook the gorgeous blue indigo dip-dye at the base of the net for a purely aesthetic flourish. The moire-patterned blue of the loose weave is exhilarating and soul-sustaining in itself, but she explained that the qualities of indigo are such that the dye-steeping gives the fabric a physical robustness, whilst also acting as a preservative against bacterial and verminous ravage. Which means that the dreamers ensconced within the net are cosseted not only by a luscious midnight hue but also by an anti-microbial and insect-repellent cordon sanitaire of organic infusion that guarantees a good night’s repose again and again throughout the half-century-long endurance of the net’s seemingly delicate fabric.

The other market treasure was even older and also hued in the glorious Japanese blue of natural indigo. Rapp’s fabulous musing over this find on her Instagram is too great not to share:

Thinking about fashion and practicality lately. I was lucky to find a pair of antique momohiki (股引) work pants at the flea market recently, and as I prepare for a fun new fashion design project I find I’m returning to these neat slacks again and again as a source of inspiration. Momohiki were an Edo era design used mostly by agricultural workers. Fitted around the ankles and calves a bit like spats and loosely tied round the hips, they’ve got all these fabulous crotch gussets that let you move in any which direction and not bust a thread. Indigo was common in workwear for its insect and fire repellant properties. Basically, these pants embody purpose-driven design, AND they’re fucken cool as. The vendor also told me they’re the preferred fashion item of the Seppuku Pistols. Sold. [via @rapprapp on Instagram]

In both the mosquito net and humble perfection of the worker’s pants we see the enmeshing of aesthetics and utility in Japanese craft traditions and are made aware of the force of time in the aesthetics, pedagogy and commerce of craft in Kyoto. The plain but profound fact about all the artisanal education and self-directed, discovery-based training availed by Kyoto’s handicraft eco-system is that the makers’ activities are necessarily time-soaked. Therefore any artefacts or remembered experiences that come from such craft processes have a complex value—an immeasurable quality rather than a calculable monetary quantity—absorbed deep within them. This is a value measured in generational spans of loyalty to the object insofar as there is an abiding sense that artefacts can and indeed should have a life that stretches out past the experiential span of a single human being; an abiding sense that everyday things such as a jacket or a curtain or a coffee cup should endure and become more precious through use and through the accumulation of memorable service and experiences directly attached to them. This service is mutual and humble—not only object-to-user but also user-to-object.

The artefacts continue to serve, continue to partake of the noble, creative process of transforming everyday life into something alchemical and metaphysical. Or devotional. By this we mean that a well-crafted object is realised through the way change gets applied to its raw material and also that this object changes the moments of ordinary time in which it gets used, making that ordinary time special in the way the object brings all its past valencies to the moment even as the moment adds yet another patina of invested time to the artefact. Every event experienced with the handicraft unfolds carefully in the flow of time, fashioned from and fashioning ordinary moments and materials burnished both by the creative intent of the maker and by the quotidian curation of the custodian, the person charged with keeping the artefact during an aperture of time before handing it along a generational chain.

To Western eyes, this looks like the animism that seems to run through much Shinto-inspired thinking in Japan—the notion that all material things have a spirit that deserves and indeed requires human ministering. At its most intense, such ministering is obvious in the care and explicit naming and characterising (often ascribing identities drawn from Noh drama) accorded to the ancient tea bowls and theatrical masks that are preserved and displayed in museums and connoisseur collections all around Japan. But at the most humble levels also—say with a lovingly preserved scarf or a shoji screen continually serving to shift the domestic space in an everyday living-room—the spirit of an object can still be appreciated as continuously present and ready for respecting. This is a true and serious devotion in a society where rituals for the proper repose of handcrafted objects are observed:

In Japan, there is a belief in a certain kind of spirit called a tsukumogami. These creatures, some say a class of yōkai, were believed to form when an item had reached one hundred years of age. Human-shaped items were believed to be specifically susceptible to becoming tsukumogami, and there were also people who believed that such items had something of a “soul “. With that in mind, and with support from the Kyoto Doll Commerce & Industry Cooperative, Hōkyō-ji holds its Ningyō Kuyō in order to soothe the spirits of the dolls that are no longer needed or have become weathered and worn. By disposing of them, not in the trash like garbage but in a proper ritual, people feel as if they are giving the dolls a more decent send-off as thanks for all the years they spent with them. (Discover Kyoto)

This abiding, immeasurable value of artefacts and the cultivation of a custodial relationship with them can be explained as ikiteiru kōgei—the integration of craft pedagogy and utility into everyday life—which is the declared theme of the current issue of Garland. In a complementary sense, it is perhaps worth re-examining the once-influential work of Ivan Illich. In his 1973 book Tools for Conviviality, Illich famously decreed that human societies must be organised around the fulfilment and conviviality that arise when people are free to make artefacts that offer them pride and pleasure as well as usefulness:

People need not only to obtain things, they need above all the freedom to make things among which they can live, to give shape to them according to their own tastes, and to put them to use in caring for and about others (Illich, Scribd online subscription edition, np).

Convivial modes of fabrication engender creative interactions linking citizens to citizens who engage constantly with a beloved, well-nurtured environment. For Illich, such non-industrial practices instruct and delight citizens about the benefits that ensure from caring for things, people and the larger environment in equal measure over sustained periods of civilised history. Such non-industrial productivity and provenance makes for the opposite of modern alienation. Thus it is not merely glib to say that the “vibe” at Chion-ji market is indeed convivial in Illich’s sense. As was our cherished interaction with the bamboo-master and his daughter.

10.

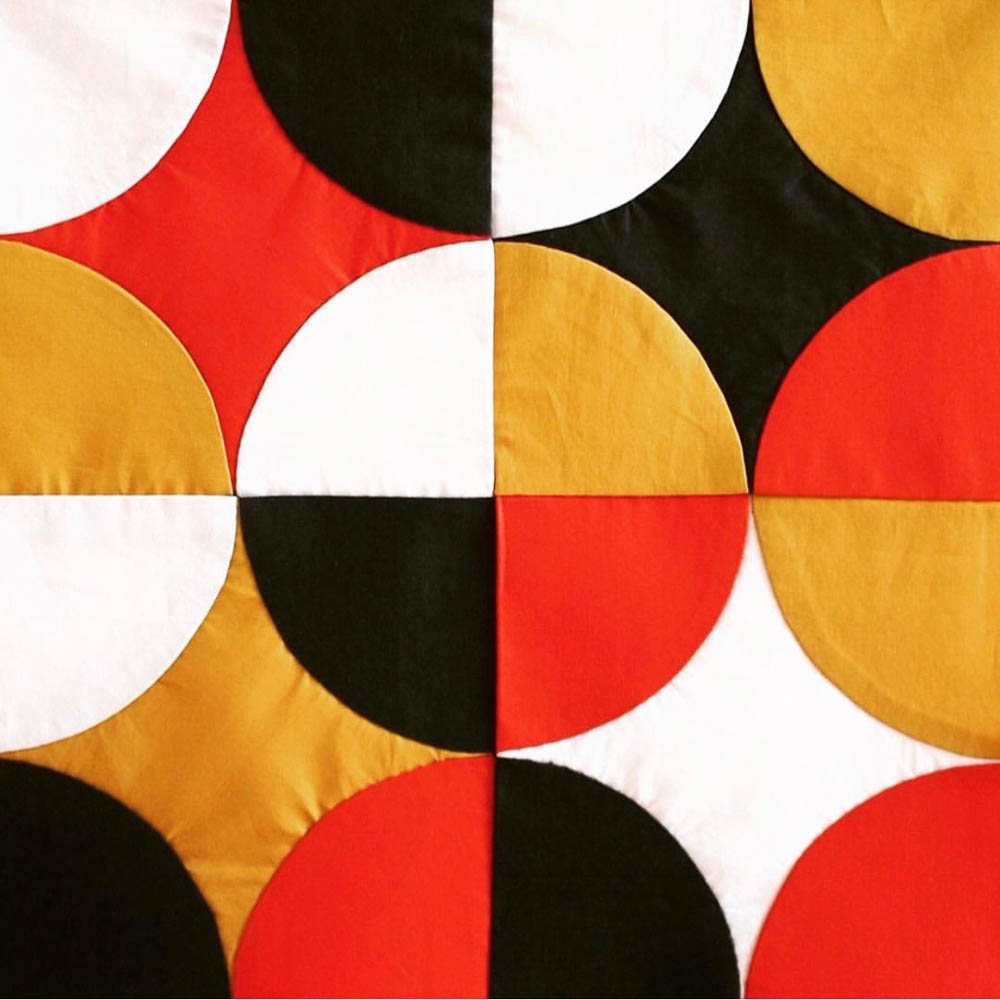

Neo-boro

Our maker-friend Yuko Sugie, who attended the natural-dye workshops with Rapp, has for several years now been a key member of Patch Work Life (PWL). A lightly-governed assemblage of Kansai-based designers, teachers and handicraft practitioners, their point of difference is that the group was founded by two young men whose background is in interior design, and not in the long-established world of (Western-influenced) patchwork and quilting in Japan. Their aim was to bring simple modern design principles to the world of patchwork and quilting, emphasising bold forms and solid colours. They’re gently pushing back a little against the prevailing Japanese “zakka” look, dominated by prints where the patterns can tend to be cutesy or twee. Sugie’s significant innovation within PWL has been to begin to explore the possibilities of patchwork beyond the bounds of the quilt or soft furnishings. She’s been developing a new look and form for the traditional Japanese embroidered motif known as the semamori, an embroidered children’s amulet. As she says on her Instagram @shimizapatchwork , “People used to sew some stitches or patchwork pieces on their children’s kimonos. They believed seams and stitches would draw in demons before they hunt the child.” Her abstracted patchworked take on semamori have now become a personal signature, sewn into some of her own clothes as well as those of her young twins.

Like other quilting groups in Japan and the world over, PWL runs workshops that bring together people of all ages and levels of experience in patchwork and quilting exercises that are as focused on the social benefits as much as on the material outcomes of the handiwork, with a commitment to spreading not just ideas but also mutual respect and a generational bridge between hand-crafters.

As PWL declare on their website, the joy that arises in the communal sense of the working-group is invincible! Dedicated to this conviviality, PWL’s workshops aim to “stimulate the five senses”, strengthen the love of community and surround its members with the sustaining spirit of long-lasting handmade textiles. Once again Ivan Illich’s ideas seem to harmonise with the Japanese handicrafters:

People feel joy, as opposed to mere pleasure, to the extent that their activities are creative … [and the human scale of hand — literally the human reach of the hand — is crucial to the production of a working joy because industrialisation and] … the growth of tools beyond a certain point increases regimentation, dependence, exploitation, and impotence. (Illich, Tools for Conviviality, Scribd online subscription edition, NP)

One of the reasons PWL emphasise the joy in their communing is that they want the knowledge to be infectious. As Sugie suggests on the website: we want to send patchwork knowledge overseas too, out from our homes. Or as Rapp put in during one of our interviews with her: “We are all keen to be part of a global network of knowledge-keepers”. In a more public and formal manner, a stunning display of Japanese craft knowledge has been sent out via Rapp’s recent exhibition, The Intuitive Thread; new expressions in Japanese textiles, presented in August – October this year at the Japan Foundation Gallery in Sydney.

When we interviewed Rapp in Kyoto earlier this year she explained how she has come to understand that many Japanese craft pedagogies and object-caring practices cause everyone who encounters the object to acknowledge and take responsibility for safekeeping the wisdom and life-experience in the object. Her work-in-progress starts, as many craft ventures do, with developing relationships with textile-savvy vendors at her local flea market (the mighty Kitano Tenmangu market, held on the 25th of every month) and through this conviviality she has built her own modest textile study collection of traditional Japanese garments—kimonos, yukatas, haoris, kimono-width bolts of fabric never made up into clothing.

As part of this “Unpicking” project she then un-stitches and thereby uncovers and foregrounds the beautiful formal logic of these garments. Seen in pieces, the kimono is a stunning example of no-waste fabrication. The panels that are joined to form the kimono are loomed at that width, avoiding the off-cut wastage that adds to the significant environmental burden of the fashion industry. Instead, the form of the kimono is reconfigured on the wearer to adapt to the circumstances of the moment using modifiers like the tasuki, a cord that holds the long sleeves of the kimono out of the way for cooking or serving.

Rapp has a particular fascination with the panels designed to line a kimono, which are historically often dyed in a contrast colour or pattern even though they will only ever be glimpsed in a flash as their wearer is walking or kneeling to sit. The part of the developing work she showed us during our visit to her Kyoto house was a stunning sampler of sorts, piecing together sections of silk kimono lining she has shaded using different natural dyeing processes, like a series of time-based experiments joined together in the form of a new bold graphical textile work. Rapp sees herself as a kind of agent to the objects, uncovering their internal logic and taking away their lessons for sustainable production and re-use, but also acting as just the current custodian in an inter-generational chain of provenance that extracts and also adds value to the artefact as it lives through several different, adaptive stages of its life. (Remember the story of her custody of the indigo mosquito net.)

Many of the works exhibited in The Intuitive Thread partake of this spirit. The most striking example is perhaps the “neo-boro” mending-aesthetic applied to old-but-also-new garments fashioned by Chiho Sasaki. The exhibition room-sheet describes the tradition that Sasaki is respecting while adapting:

Derived from the mimetic boroboro meaning worn out and ragged, this method aims not to hide but to expose the naturally worn beauty of cloth, extending its life through resourceful patching, applique and sewing techniques. Old and discarded fabrics are reworked to create new possibilities. Through considered use of these boro methods Sasaki creates garments that embody the sabi aesthetic through their rough beauty and proud display of natural wear and tear.

As Rapp explains, the exhibition is a culmination of her recent hands-on research in Japanese craft aesthetics and ethics. And as we review our own appreciation of the craft-spirit of everyday Kyoto, we recognise the special qualities of the Old Capital, especially the opportunities afforded here to reconsider the importance of time, relationships and place in handcrafted objects.

11.

The needle shop

In this walking city, a favourite day in any visit to Kyoto is the day spent with Yuko making our pilgrimage from yarn shop to fabric shop to dye shop to our beloved Tokyu Hands. All of these places are thriving. The world of handicrafts is alive and well and thronging with makers. We had a thrill one day seeing a geisha (not one of the many imitators) on the escalators in Tokyu Hands, perhaps even she is in the ranks of Kyoto crafters. In our walk, we make sure to loop in a visit to one of the most lovely shops in all the world, the very tiny, very beautiful, very specialist, very hard to find Misuyubari needle shop.

Walk west down Sanjo-dori arcade from where it meets busy Kawaramachi-dori. Walk past the old shop selling Buddhist supplies on your right. If you’ve come to the old knife and scissor shop on your left you’re in the right area. Behind you is a non-descript passage, which opens out to the magnificent Japanese garden dwarfing the needle shop beyond. Inside the shop there are needles and thimbles in all gauges and an exquisite display of silk sashiko thread in a myriad of colours. The last time we visited and asked how the store was going, the man ruefully cocked his head to the side and sucked in air, then ventured “not so many people”. This business has been in his family for 350 years. The thought of a Kyoto without this needle shop in it is heartbreaking.

We can’t even bear to walk east down Sanjo dori towards the mountains, towards the shop of the elderly bamboo-master. Our previous encounter with him and his craft was eight years ago and the shop will surely no longer be there. So make haste, go to Kyoto, make time, seek out a traditional craftsperson then spend time (and if you can, money).

May we suggest taking a bus ride out to the countryside to meet Hiroyuki Shindo, the great indigo artist? He has his succession plan in place—a son and daughter in law to take over the delicate business of tending the indigo vats, alive like sourdough and requiring careful attention. If you slow down there’s a lot to learn on a visit to his “Little Indigo Museum” and you can take away an embodied instance of his time and care and skill in the form of some of his beautiful dyed textiles. At the talk by Japanese indigo artist Chiharu Ohgomori in Sydney, one of us was wearing a scarf made by Shindo-san. This brilliant, innovative craftswoman spotted it, stopped mid-sentence, stood back and responded to the time and care inherent in this single item with a muted gasp of wonderment.

All images are by Kathryn Bird. Full photo albums can be found of textures, markets, contemporary design and craft, shopping for traditional crafts,

Authors

Kathryn Bird is an artist, specialising in collage, and a book designer, specialising in art books. Most recently she was an artist in residence at the “Gods of Tiny Things” collage camp at Bundanon, and a reader in residence at The Peoples Library of Tasmania in Hobart. She is a member of the international collage group “The Collage Club” and the founder of the Sydney collage group “The Social Glue of Sydney” (More info on both groups on instagram, at @thecollageclub and @thesocialglueofsydney, respectively). She has recently returned from a 5-week collage + walking sabbatical in Kyoto, and travels to the city at least once a year. She can be contacted regarding specialist guided tours of Kyoto at @handcraftedkyoto on social media.

Kathryn Bird is an artist, specialising in collage, and a book designer, specialising in art books. Most recently she was an artist in residence at the “Gods of Tiny Things” collage camp at Bundanon, and a reader in residence at The Peoples Library of Tasmania in Hobart. She is a member of the international collage group “The Collage Club” and the founder of the Sydney collage group “The Social Glue of Sydney” (More info on both groups on instagram, at @thecollageclub and @thesocialglueofsydney, respectively). She has recently returned from a 5-week collage + walking sabbatical in Kyoto, and travels to the city at least once a year. She can be contacted regarding specialist guided tours of Kyoto at @handcraftedkyoto on social media.

Ross Gibson works in the Centre for Creative & Cultural Research at the University of Canberra. Recent books include The Criminal Re-Register, Changescapes and Memoryscopes, all published by UWAP.