- Master Navajo weaver Florence Manygoats rests on her land in Arizona surrounded by her colorful rugs woven in various Navajo styles.

- Barbara Teller Ornelas and Lynda Teller Pete, photo: Joe Coca

- Stacked diagonal stairstep designs are a signature feature in rugs woven by Regina Charley.

- Barbara Omelas, Heard rug

Barbara Teller Ornelas and Lynda Teller Pete introduce us to the ancient myth and bright future of Navajo rug weaving.

(A message to the reader.)

Spider Woman’s Children by Barbara Teller Ornelas and Lynda Teller Pete introduces the past and present traditions of Navajo rug weaving. Ornelas and Teller are themselves fifth-generation weavers who grew up at the fabled Two Grey Hills Trading Post. They draw on their family and clan connections to offer insight into the world of Navajo rugs.

Here they offer an account of the Spider Woman story that underpins this tradition:

In Navajo tradition, the span of time from the first creation to the present day is composed of five worlds. We live in the current fifth world, “Glittering World.” In the emergence from the second world to the third, our Holy People, Diyin Dine’éԀ, instructed Spider Woman to weave her pattern of the universe. Then she was to teach the Diné, the Navajo, to weave Hozho (beauty) to bring harmony and beauty into their lives. She had no knowledge of how to do it. But Spider Woman was observant; she watched everything in her environment, and her curiosity focused on a spider weaving a web. This became her plan for how she would weave the universe. When she felt comfortable with her experimental weaving, she returned home and presented it to her husband, Spider Man. With just this basic concept of weaving, the Holy People instructed Spider Woman so that her skills would be further enhanced by prayer, songs, and ceremonial duties.

Spider Woman was told to go to our four sacred mountains to gather specific items to further advance her weaving: Blanca Peak, the sacred mountain of the east, Sisnaajiní, “the dawn,” or “white shell mountain”; Mount Taylor, the sacred mountain of the south, Tsoodził, “turquoise mountain,” or “blue bead”; San Francisco Peak, the sacred mountain of the west, Dook’o’oosłííd, “the summit which never melts,” or “abalone shell mountain”; and Hesperus Mountain, the sacred mountain of the north, Dibé Nitsaa, “big sheep.” From the first mountain, she got wood for Spider Man to make the loom. From the second mountain, she harvested plants for vegetal colors for her wool. From the third mountain, she got patterns from the thunder gods, from whom she asked permission to use the patterns in her weaving. They granted her permission and told her to learn and teach the patterns so that other weavers could use them. From the last mountain, she got prayers and songs that are associated with all stages of weaving.

And for Garland magazine, they offer four profiles, including one legendary artist and three of the next generation Navajo weavers.

Irene Hardy Clark

- Irene Clark works at her loom where she has been weaving for several decades, Photo: Joe Coca

- Irene Clark is a natural dyer, weaver, and keeper of Navajo textile traditions., photo: Joe Coca

- Irene collects dye materials as she walks across her land in New Mexico. Sage, lichens, and blue corn are among the many dyestuffs she uses, photo: Joe Coca

Crystal, New Mexico

Born of the Water’s Edge Clan, Tábąąhá

Born For One-Walks-Around Clan, Honágháahnii

Irene was born in 1934 and raised in Crystal, New Mexico. Her mother was master weaver Glenabah Hardy; Irene weaves in the same Crystal style as her mother and grandmother. Irene didn’t start weaving at an early age. Instead, she herded the family’s flock of sheep. But when she returned the sheep to the corral, she would watch her mother weave, and these visual lessons stayed with her.

Irene attended Chilocco Indian School in Oklahoma, where she met her husband, Jimmy. When she returned home, she finally began weaving. For her first rug, she asked her mother to just watch her and to point out weaving errors. With no hands-on lessons, she had basically taught herself by watching, listening, and figuring out the challenges her grandmother and her mother encountered in their weaving. She sold her first rug to a trading post for 400 dollars.

Irene learned the traditional way of weaving, first preparing her materials, carding, spinning, collecting plants for dyeing. Finally, with the proper Navajo weaving songs, she would start weaving. Songs, prayers, and good thoughts are associated with every step of her weaving. She is mindful that each rug has to be finished, each rug teaches her something new, and she never leaves her loom empty for too long.

Irene said, “I do my blessing before each rug. I thank Mother Earth for the plants that give color to my wool, for the sky above me, the air I breathe, for mother earth for grounding me. All this gives me a good feeling to weave.” Irene explains, “Everything is in the weaving, it’s in your hands, it’s in your weaving tools, and it’s in your mind. Design and dyeing are related to how you think of yourself, and it will show in how you weave your rug. Good thoughts, prayers, songs are what you need.” Irene’s rugs tell her stories; some tell of her struggles to succeed, but all tell of her connection to the harvested plants that provided the beautiful dyes for which she is known. Dyeing is in her family.

Irene’s mother, Glenabah, was known for a particular design she often wove in her Crystal rugs—two inverted triangles with a square in the middle of the triangles, a design that would please algebra and geometry teachers. The design element represents a tsiiyéél, the hair bun worn by Navajos. After her mother passed, Irene has continued to weave this design to honor her mother.

Irene is a well-traveled weaver. We first met in 1992 at the opening of Reflections of the Weaver’s World: The Gloria F. Ross Collection of Contemporary Navajo Weaving at the Denver Art Museum. As the exhibit traveled, we met in museums in other cities, the most memorable being the George Gustav Heye Center in New York. Irene wore Navajo clothing and her jewelry was beautiful. The rotunda at the Heye Center was filled with Navajo weavers, many in their most elegant clothing, and you could hear the Navajo language bouncing off the walls, creating an echo that sounded like songs. After meeting Irene many times at different Navajo weaving events, we finally had quality time to talk about weaving when we both attended the Navajo Weaving Now! conference in Tucson in 2005. We are of the same clan, Water’s Edge Clan, Tábąąhá, so we are related; after we talked about our weaving, we became family.

Irene’s weaving accolades are many, but the ribbons for those countless weaving career achievements she tucks away. Still humble about her work, Irene says, “My current rug always teaches me something new; I am going to challenge myself to do better.” Because she has this relationship with each rug she weaves, Irene feels like she has given a piece of herself away when she sells a rug, having put so much of herself in the weaving. Sometimes she even misses a rug after she sells it.

Irene also has been an important weaving teacher—it is one of the many ways she has passed on the heart of her Navajo traditions. She encourages her students to remember their prayers and their songs. “We are carrying on the Holy Ones’ work,” she reminds them. Irene is a weaver who honors the Holy Ones and Spider Woman in all her work and in all her words.

Roxanne Rose Lee

- Roxanne Rose Lee, the grandniece of authors Barbara Teller Ornelas and Lynda Teller Pete, learned to weave when she was just four years old. As a seventh-generation weaver, she takes the responsibility of her heritage and her family traditions seriously., photo: Joe Coca

- Roxanne works together with her great-aunt Lynda who has been an important mentor., photo: Joe Coca

Tucson, Arizona

Born of the Mexican People Clan, Naakaii Dine’é

Born for The Water’s Edge Clan, Tábąąhá Father’s Father, Red Bottom People, Tł’ááshchí’í

Roxanne Rose Lee is a seventh-generation Navajo weaver, sixteen years old, and in the eleventh grade. She is the granddaughter of master weaver Rosann Teller Lee, and is grandniece to Barbara Teller Ornelas and me, Lynda Teller Pete—though according to Navajo custom, we call her our granddaughter, too. Roxanne’s mother, Julie Charles, is in the U.S. Army and stationed at Fort Lewis, Washington, currently serving her seventeenth year. Roxanne lives in Tucson with her father, Terry Lee, Navajo weaving tool craftsmen and a self-employed artist.

Barbara and I began to teach Roxanne how to weave very early—at age four! When young children are first introduced to a Navajo loom during Barbara’s and my Navajo weaving classes, most grab the warps and pull and bang on things with the weaving tools, seeing the loom and tools as new toys. But when my husband, Belvin, sat Roxanne in front of a Navajo loom for the first time, she strummed her fingers across the warps, picked up each color of the wool and tucked them inside the male/female warps, and flipped the batten up as an experienced weaver would do. We looked at each other in astonishment that Roxanne innately knew how to treat the Navajo loom at age four.

Roxanne says, “Navajo weaving is a way of life for my dad’s side of the family. I got my first loom when I was four, and finished my first rug, a colorful sampler woven with commercial wool, when I was ten. My grandma Lynda bought it.”

When Roxanne finishes her homework on school days, she weaves two hours a day, and more hours on the weekend. She received her first blue ribbon in 2013 at the Santa Fe Indian Market for a small rug woven with her own design elements using commercial wool. This rug was sold along with her grandmother Barbara’s rug, and she is happy both weavings will be together.

Roxanne said, “Weaving is very important in our family. For four summers, I have spent two weeks in my grandmothers’ annual Navajo weaving class at Idyllwild School of Arts. In each of those summers, I have finished one or two weavings and have entered them in the youth division at Santa Fe Indian Market.” These rugs Roxanne finished in our classes were woven with commercial wool and, important to note, she wove her own designs in them—unlike us when we were her age. Roxanne says her rugs have no particular Navajo style, just her own style. Each rug entered into the Santa Fe Indian Market has received ribbons, all first places, and all have sold.

Roxanne says, “My grandmothers have told me about our Navajo history and our relatives’ weaving history, but it wasn’t until I was in the classroom and watching other kids my age learning for the first time that I realized how important it was for me to know my history. I think it is important to know your history, and if some kids my age do not know how to weave, there should be places for them to learn. My grandmothers told me about Navajo organizations that seek funding to help Navajo kids and maybe adults to learn how to weave or to receive assistance in selling their work. I think this is a good idea and if I can help when I become more experienced, I would like to do that.”

In 2017, Roxanne entered her Burntwater-style tapestry, her first tapestry using very fine weft wool spun by her grandmother Barbara’s and my vegetal dyed wool, in the Navajo Weaving Youth Division at the Santa Fe Indian Market and won first place. Her tapestry was bought by the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture in Santa Fe, New Mexico, and will be exhibited along with the tapestries of Barbara, Lynda, and her uncle Michael.

Roxanne’s quest for weaving inspiration is amazing; her zeal for creation is fearless beyond artistic boundaries. In all the years that I have taught people, all ages, both genders, diverse nationalities, there are standouts every now and then, and I feel proud to be a part of their weaving journeys. Much to my delight, here in my own family, Roxanne is a standout as a young Navajo weaving artist with a strong desire to maintain her own Navajo traditions.

Michael Paul Teller Ornelas

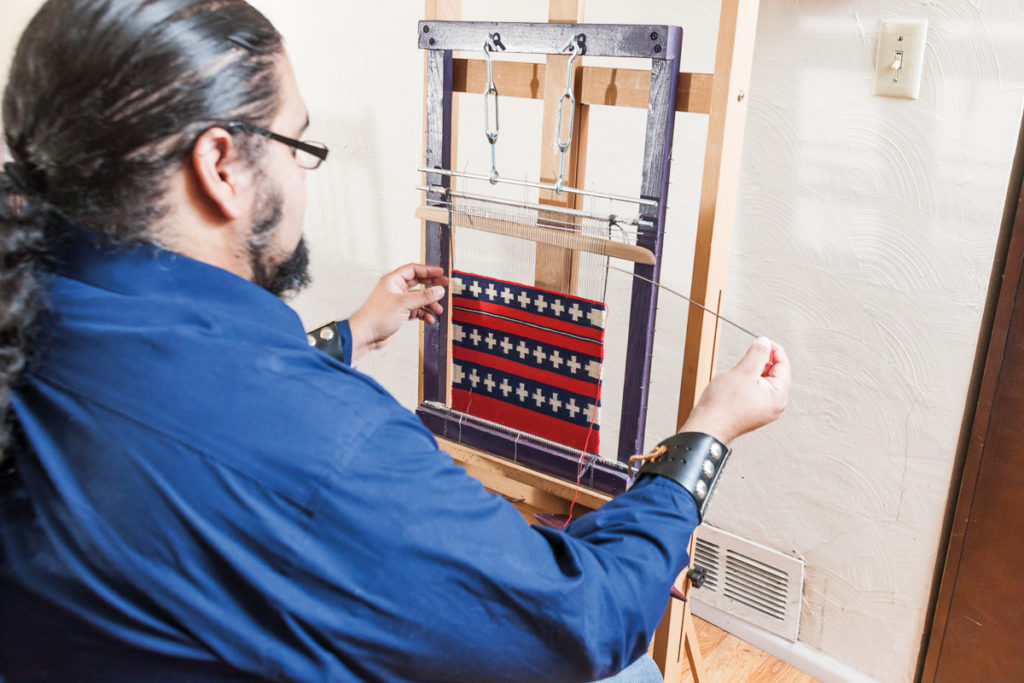

- Michael Teller Ornelas blends tradition with innovation in his Navajo rug designs., photo: Joe Coca

- Michael weaves a small tapestry with a more traditional sensibility., photo: Joe Coca

Tucson, Arizona

Born of the Water’s Edge Clan, Tábąąhá

Born For The Mexican People Clan, Naakaii Dine’é

Mother’s Father, Water-Flows-Together Clan, Tó’aheedlíinii

Father’s Father, Mexican Clan, Naakaii Dine’é

Michael has been weaving since he was thirteen, when he asked his mother to teach him. She set up a warp and was amazed at how quickly he picked up the skills.

At mere suggestions to watch his edges, weaving too tight, too loose, he was a quick study and started doing complex designs. When he was eighteen, his child’s blanket earned Best of Show at the Heard Museum’s 2003 student competition. Some of his tapestries are also in the Heard Museum’s permanent collections.

As a computer science major at the University of Arizona, Michael used his computer to map out design ideas for his weavings early in his weaving career. During the same time, he took a part-time job with the Arizona State Museum’s Gloria F. Ross Center for Tapestry Studies and worked as a web developer. He was tasked with creating a website that allowed users to search and explore the Joe Ben Wheat South-west Textiles database. The Arizona State Museum had vast information on nineteenth-century Navajo blankets. The user could make search queries based on a rug’s size, pattern, age, weaver, and handspun or commercially processed wool weft types. (The website, unfortunately, is no longer accessible.)

Michael says, “Weaving has always been about breaking barriers for me. I grew up with stories about how my mom challenged the status quo, selling directly to customers and museums instead of going through dealers and galleries. So I couldn’t help but question why my mom, this trendsetter, was saying I couldn’t branch out. Her standard response was, ‘Because you just can’t!’” Michael and his mother would laugh because they both knew it was not a good answer and after some talking, Barbara remembered having the same arguments with her mother. In time, his mother found trust in his ideas, letting go of her restrictions imposed by her mother and let Michael experiment with color and design.

Michael remarked, “Weaving designs have always been changing despite what we were initially taught. I looked for my surrounding environment like the weavers of old. They would use the surrounding environment of nature, of the land. I used my current surroundings of technology and electronics. So while weaving designs have always been changing, the challenges and skills of weaving will always connect us together.”

Some years, the economy has resulted in a down market for Indian art collectibles, so Michael started weaving miniiatures with design motifs from pop culture, video game avatars, and Japanese anime, as well as traditional Navajo design elements, and he put these textiles into art frames. Younger people started their weaving collections with his miniatures, and they would not just buy one; most bought two to four at each show.

Michael says, “I’ve been doing tapestry miniatures for a long time. Small weavings that are around five inches by five inches because they let me quickly prototype and experiment with design elements—abstracts or my family’s traditional Navajo designs. It’s been a ton of fun to see what I can do with designs and colors.” Recently he’s been moving back into weaving larger pieces, though. “I want to take what I learned doing the miniatures and apply it to large-scale projects. I’ve been working with my mother on a few projects. We will usually call each other into our workrooms to trade ideas and conference about patterns and problems. It has been a validating experience to have my mom, the great master weaver, reliably come to me when she’s having an issue. And, of course, she’s been a great resource for me with her years of experience and knowledge.”

Michael had four of his tapestries, a Two Grey Hills tapestry, a pop culture–influenced pictorial on the comic book hero, Spider-Man, and two of his signature miniature weavings—a complete representation of his weaving styles—on exhibit at the Amerind Foundation and Museum in Dragoon, Arizona. The exhibit featured contemporary weavings by young Diné artists entitled Gifts from Spider Woman’s Grandchildren in 2012.

Today, Michael has moved away a bit from being inspired by pop culture for his rug designs. He explains, “It’s not that I’m not influenced by it, but my focus is more on the complexity of my designs. How far is too much? How strong is simple? How do I keep a good rhythm and balance between all the elements of the rug? I’m confident that I am better than I was five years ago, but I still wish to be better than I am today.” During the 2017 Santa Fe Indian Market in Santa Fe, New Mexico, Michael’s Two Grey Hills tapestry was purchased by the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture and will be exhibited along with Barbara’s and my Two Grey Hills tapestries and a Burntwater tapestry by granddaughter Roxanne. Michael is doing the full circle back to his traditional roots of weaving mainly Two Grey Hills tapestries and Barbara and I, we are smiling from ear to ear!

Velma Kee Craig

Velma Kee Craig is a contemporary face of Navajo weaving. She incorporates contemporary life and popular culture into traditional Navajo designs. photo: Joe Coca

Mesa, Arizona

Born of the Zuni Water’s Edge Clan, Naasht’ézhí Tábąąhá Dine’é

Born For The Bitter Water Clan, Tódích’íi’nii

Mother’s Father, Many Goats Clan, Tł’ízí Łání

Father’s Father, Towering House People, Kinyaa’áanii

Velma Craig’s childhood was marked by frequent moves. She moved with her parents, Laverne Marks Mandia and Larry Kee, from Tonalea, to Page, to Fort Defiance, to Klagetoh, and back to Fort Defiance where her parents were finally able to establish a permanent home for themselves and their four children. In Tonalea, Velma’s family stayed with her maternal grandmother, Elva Marks. Velma watched her grandmother process wool; she herded and cared for the sheep, sheared the wool, carded, washed, and dyed the wool. As family members shared stories, Velma learned that her grandmother was also a weaver. There are a few old photos of her holding up a finished textile. Velma inherited her grandmother’s weaving tools.

During fourth grade, Velma’s family moved over to her father’s side of the reservation and lived briefly with her paternal grandparents. Her grandmother wove all the time while the grandchildren watched television and played nearby. This is a lasting memory that Velma treasures, the time spent watching her grandmother weave. She enjoyed the methodical movements of her grandmother’s hands and fell in love with the sounds of weaving and the warm, earthy smells of the sheep.

After graduating from Window Rock High School in 1995, Velma earned her BA in English literature from Arizona State University in Tempe and is working toward a master’s degree in creative writing. In the meantime, she is learning museum and library studies (emphasis in textile conservation and long-term care) as an Andrew Mellon Fellow at the Heard Museum in Phoenix. The time finally came for Velma to make weaving a part of her life. She and her daughter Ashlee took a two-week class with Barbara and me at the Idyllwild Arts Academy in 2010 and weaving began to take off for her. Her first weaving was sold to the Heard Museum. Up until this point, she says, “I was very timid in trying to market myself as a weaver. I didn’t weave full-time or quickly. I was still unsure about my skill level and didn’t have as much confidence as I thought I should have.”

Now Velma sells her work through social media and through the stories she tells on her blog Warped Canvas,. She’s currently working on a rug design based on the Finding Nemo movie that has been dubbed in Navajo.

Velma’s journey back to Navajo weaving took a while, but once she immersed herself in learning, she wanted to teach other Navajos like herself. She says, “I love teaching! Especially, because my students are primarily Navajo. I have been lucky to fall into working for organizations that have received funding for cultural revitalization and education. Every student comes to the class with a different level of knowledge of the techniques and the philosophy and history of weaving, and of Navajo culture in general. They are diverse in their understanding and in their beliefs, even though we are all Navajo.

“I think they appreciate that I, too, am a classroom learner. This makes them less self-conscious. I encourage them to share with others the knowledge they bring and also their stories. I also encourage them to encourage one another. I tell them they are part of a weaving culture. They will leave this classroom with the understanding that they will seek knowledge from other weavers beyond me, from their elder family members. I tell them weaving is a continual learning journey. They must also be willing to accept help and critique. So far,

they have been. We have all become more humble on this journey.” Because of the nomadic lifestyle her family experienced in her early years, Velma did not know the styles that her grandmothers wove. Essentially, this has given her the freedom to weave rugs about herself, her discoveries, and her dreams; it allows her to infuse her artistic voice in the weavings to make sense of the world. She has the freedom to create abstract contemporary styles and maybe mix in a touch of trading post styles—or not!

Velma lives in Mesa with her four children, Kraig, Chance, Ashlee, and Tristan.

Photographs by Joe Coca courtesy of Thrums Books Thrums Books (ThrumsBooks.com) from Spider Woman’s Children: Navajo Weavers Today. Copyright 2018, Lynda Teller Pete Pete and Barbara Teller Ornelas

Photographs by Joe Coca courtesy of Thrums Books Thrums Books (ThrumsBooks.com) from Spider Woman’s Children: Navajo Weavers Today. Copyright 2018, Lynda Teller Pete Pete and Barbara Teller Ornelas

This story is extracted from Ornelas, Barbara Teller, and Lynda Teller Pete . 2018. Spider Woman’s Children: Navajo Weavers Today. Thrums Books (or on Booktopia for orders outside the US)

Authors

I am Barbara Teller Ornelas, Master Navajo Weaver.I come from the Navajo Nation. I’m a 5th generation weaver. I was taught the songs and prayers for weaving from my grandmothers, the basic weaving and the art of demonstrating from my mother. The designs and techniques from my older sister. Weaving is my life and it’s what brings me my balance. When you see my weavings, you see me and when you see me, you see my weavings.

I am Barbara Teller Ornelas, Master Navajo Weaver.I come from the Navajo Nation. I’m a 5th generation weaver. I was taught the songs and prayers for weaving from my grandmothers, the basic weaving and the art of demonstrating from my mother. The designs and techniques from my older sister. Weaving is my life and it’s what brings me my balance. When you see my weavings, you see me and when you see me, you see my weavings.

From the age of six, when Lynda was officially introduced to weaving, instilled the belief that beauty and harmony should be woven into every rug. In our Teller family, we regard weaving as our life’s work. Weaving represents our connection to the universe. It is our stories, our prayers, and our songs that are told, chanted, sung, and preserved in the weaving motions. Every weaver has stories to tell about his or her weaving, and every weaving has stories to tell about the weaver: the sights, the sounds, the smells, and the signature styles. And each weaver is unique. I touch tapestries woven by my grandmothers, my mother, my sisters, my cousins, my niece, my nephew, and my granddaughter. I see their hands strumming the warps. I hear the resonating beats of their weaving combs, and without seeing them, I know who is weaving just by the sound of their beats. I see tears, fears, and joy, and I hear laughter, soothing words of comfort, and loud congratulatory cheers. Unlike our elder Navajo weavers, people will know our names; they will see our faces, know our stories, and they will hear our songs and our prayers on each tapestry that we create. Today, Lynda Teller Pete continues to carry this weaving tradition.

From the age of six, when Lynda was officially introduced to weaving, instilled the belief that beauty and harmony should be woven into every rug. In our Teller family, we regard weaving as our life’s work. Weaving represents our connection to the universe. It is our stories, our prayers, and our songs that are told, chanted, sung, and preserved in the weaving motions. Every weaver has stories to tell about his or her weaving, and every weaving has stories to tell about the weaver: the sights, the sounds, the smells, and the signature styles. And each weaver is unique. I touch tapestries woven by my grandmothers, my mother, my sisters, my cousins, my niece, my nephew, and my granddaughter. I see their hands strumming the warps. I hear the resonating beats of their weaving combs, and without seeing them, I know who is weaving just by the sound of their beats. I see tears, fears, and joy, and I hear laughter, soothing words of comfort, and loud congratulatory cheers. Unlike our elder Navajo weavers, people will know our names; they will see our faces, know our stories, and they will hear our songs and our prayers on each tapestry that we create. Today, Lynda Teller Pete continues to carry this weaving tradition.

Comments

Read this

I’m sure I have one of these rugs it’s large and I have had it for 50yrs or more

Thank you Garland, and Barbara for your beautiful message.

I love the story of Spider Woman!

Especially the focus in how observant she was – how she watched everything in her environment.

Also the part about asking the thunder gods for permission to use their patterns in her weaving.

It’s so great to see both the master and the emerging weavers profiled here, and to read Michael saying he looked to his surrounding environment like the weavers of old. I agree that “while weaving designs have always been changing, the challenges and skills of weaving will always connect us together.”

A wonderful article, thank you. I taught and lived on theNavajo Nation for nearly twenty years – learning so much. I tried to weave and was “all thumbs.” I look forward to purchasing the book and learning more.