植物とパンクと禅とスローアート

any point of a rhizome can be connected to anything other, and must be. (Guattari and Deleuze, p. 28)

Lettuce is “retasu” in Japanese. The actual thing looks similar enough, both in Australia and Japan. The “Jap Pumpkin”, however, is not quite the same as the pumpkin you get in Japan. It is said here, in Australia, that the pumpkin belongs to the “cucumber family” whereas in Japan they are mostly said to belong to the “chestnut family”. What is more, they taste completely different.

Run lines, never plot a point! Speed turns the point into a line! Be quick, even when standing still! Line of chance, line of hips, line of flight. (p. 45)

When I was in Japan (my place of birth where I spent my teenage years, later going to Boston and Paris before finally settling in Melbourne), I was constantly reminded that my way of thinking and how I am does not fit in a typical Japanese cultural framework. Nevertheless, when I stepped out from Japan, Western people saw me as much more “Japanese” than “Western”. My children, who grew up in Melbourne, are much more comfortable communicating in English. Their “Japaneseness”, however, is profoundly permeated throughout their identity. So, are they more Aussie or Japanese? Such a discussion itself is much outdated and meaningless. Who cares? They are likely part of a nexus that will help form a new culture and history in Melbourne.

A rhizome ceaselessly establishes connections between semiotic chains, organizations of power, and circumstances relative to the arts, sciences, and social struggles. (p.24)

When I officially started my career as an “artist” after school, I did not know what the core values of my art would be. I was with a commercial gallery, using humble materials like old sheets to create sewing machine drawings. But somehow, I felt that this may not be the right direction for my art practice. This was partly because I did not know how to justify my “Japanese essence” in practice and how to contextualise this very struggle to attain a definition.

It has neither beginning nor end but always a middle from which it grows and which it overspills. It constitutes linear multiplicities with in dimensions having neither subject nor objects, which can be laid out on a plane of consistency… (p.42)

Anytime I get stuck, I look to plants to try and learn something from them. I particularly look to weeds, or the shoots that sprout out from vegetable scraps. I ponder how the growth process unfolds beneath the earth, or under water. Vegetation is not concerned with anyone, its existence is quiet, but at the same time subject to incredible innate energy. Rhizome theory, which resonates with Zen texts, as well as the subversive revolutionary spirits of punk and jazz, provided me with profound insights and inspiration.

Empty your mind, be formless. Shapeless, like water. (Bruce Lee)

Although I would not go so far as to say that the concept has been directly realised in my art practice, I knew that my art could only be derived from what I truly possess within me. So, what was it that I possessed? What I valued the most were those small things that occur in ordinary, everyday life and their coexistence with the extraordinary. Something, somewhere, is always slowly and silently beginning to grow, at random. It continues to grow before something extraordinary appears, all of a sudden, out of the blue—potentially a moment of “art”.

A new rhizome may form in the heart of a tree, the hollow of a root, the crook of a branch. Or else it is a microscopic element of the root-tree, a radicle, that gets rhizome production going. (p. 36)

Everything, including art, is impermanent, subtle and not necessarily visible to everyone. It is made up of ephemerality, in-betweenness, plasticity, anonymity, repetition, hypnotic, illusion/delusion, impro and a process base. I wanted to see what would occur if I just let everything proceed randomly without my control. It was something that I was fascinated by, beyond the geographical boundaries of Japan or Australia.

The rhizome is an antigenealogy. It is a short-term memory, or antimemory. The rhizome operates by variation, expansion, conquest, capture… (p. 42)

It was around this time, looking at weeds in my garden whilst harbouring such thoughts, that my son was born, and the world had started to witness a world-wide emergence of the Slow Movement. The movement caught my attention, as it resonated with the plant world. Whilst not a very “Japanese” concept, it had the potential to be. The movement was also adaptable to any area. Perhaps what I liked most about it was the fact that it is not a special term exclusive to art, even though it was almost too simplistic, it is accessible to just about anyone in the world. In my art practice, I wanted to be able to reach out to everyone.

It is composed not of units but of dimensions, or rather directions in motion. (p. 42)

I was particularly keen to create something stemming from specific spatial dialogue, that would not simply be reduced to being labelled “site-specific”. Just as with the growth process of weeds, art has the potential to sprout out from any potentially inter-dependent segment, including small happenings found in everyday life.

The rhizome is made only of lines: lines of segmentarity and stratification as its dimensions, and the line of flight or deterritorialization as the maximum dimension after which the multiplicity undergoes metamorphosis, changes in nature. (p. 42)

It shares “time”, “space”, “process”, and is infinite. Boundaries are blurred: there is no definite “artist” or “viewer”. No definite “process” or “complete” work. No polarity; it is a chaotic state that can coexist with absolute stillness, not unlike an amalgamation of the spirit of punk and Zen.

The East: horticulture based on a small number of individuals derived from a wide range of “clones.” Does not the East, … offer something like a rhizomatic model opposed in every respect to the Western model of the tree? (p. 42)

So, what is “Slow Art”? It is not “spending much time viewing paintings and contemplating the work”, nor is it “spending a long time creating a very complex work”. For me, Slow Art is more like the rhizome growing silently underground, in multiple directions, creating a subterranean network and system by itself. It is more about the system rather than aesthetics and formal outcomes: it is about process.

What is and what is not create each other. (Tao Te Ching Chapter 2)

The rhizome may be seen as the opposite of a tree structure. All elements grow in their own direction on their own accord. They look chaotic, and yet they are simple. This is similar to Zen’s koan, a concept whereby opposing ideas can coexist. It is a concept which is often attributed to Eastern ways of seeing things.

The tree is filiation, but the rhizome is alliance, uniquely alliance. The tree imposes the verb “to be,” but the fabric of the rhizome is the conjunction, “and. . . and.. . and. . .” (p. 46)

Slow Art Collective started almost by chance. It started as a small seed and kept evolving and growing enormously. We started with four artists but two now the leading artists (Dylan Martorell and I ) act as the “core” members and anyone can jump in and get involved with the creation process in accordance with the nature of the project. It has been about 10 years since we began, and there have been more than 40 artists/friends/kids who have actively participated.

Nothing is as it seems, nor is it otherwise. (The Daily Zen)

We do not want to control direction. Instead, we want to be intuitive and responsive. Both Japanese and Western ways of thinking can coexist, much like a rhizome. The question of what “Slow Art” and “Japaneseness” is, will probably keep me engaged for the rest of my life. And the answer will keep on changing.

Unless otherwise stated, quotes are from Pierre-Félix Guattari and Gilles Deleuze, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, translation and foreword by Brian Massumi, University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, London, 1987, online PDF version

This is an early work and probably the first large installation where I was able to achieve complete communication with the surrounding space whilst only relying on string and pre-existing artefacts. I did no planning for this design. Using string, I simply began to interconnect trees, one-by-one, with the earth. As I continued to do so, the installation grew eventually taking on its own form.

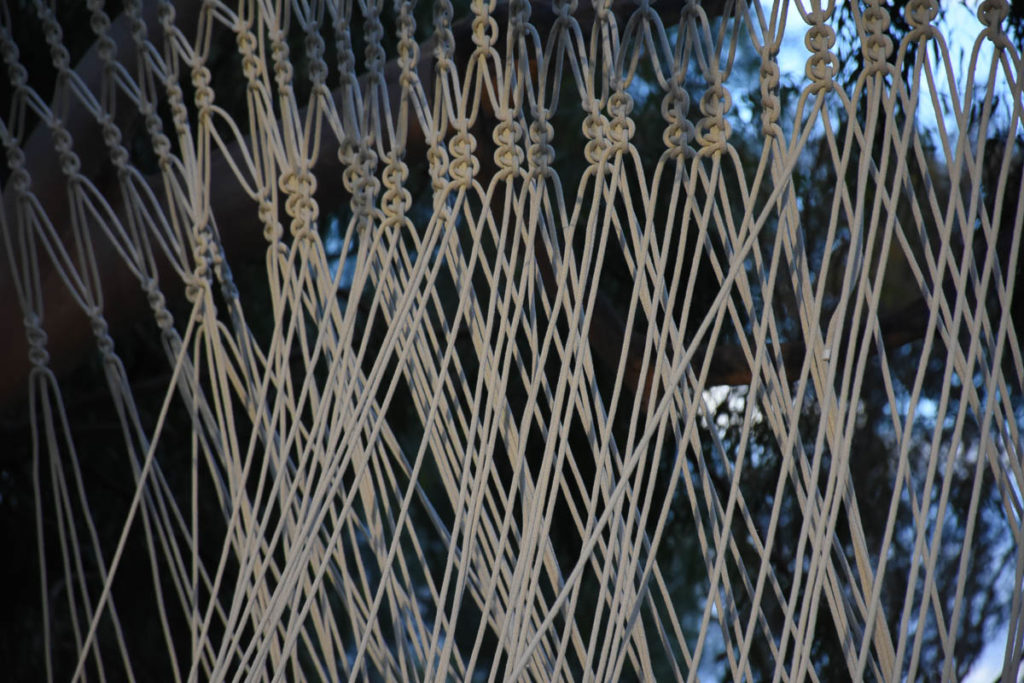

Whilst using string I found that a key issue was scale. The scale would grow and grow, not unlike a rhizome system. Perhaps this is something that is innate to all human beings? This photo is of a section of an installation I spent more than a month and a half on which was featured in the McClelland Sculpture Survey and Award. After spending such a long period of time on the installation I began to feel as though I myself was part of the vegetation. I would tie a knot from spot to spot creating a line before repeating the action over and over again. Through this continuous and repetitive, rhythmic action I was able to achieve new levels of appreciation for these actions as associated with drawing. This was, once again, a completely improvised process with no planning what so ever. My aim was to realise a space that harmonised the chaos of discord and fragmentation with the serenity associated with Zen. Moving infinitely from one point to another may be seen as a meditative process which, at the same time, is on the border with insanity.

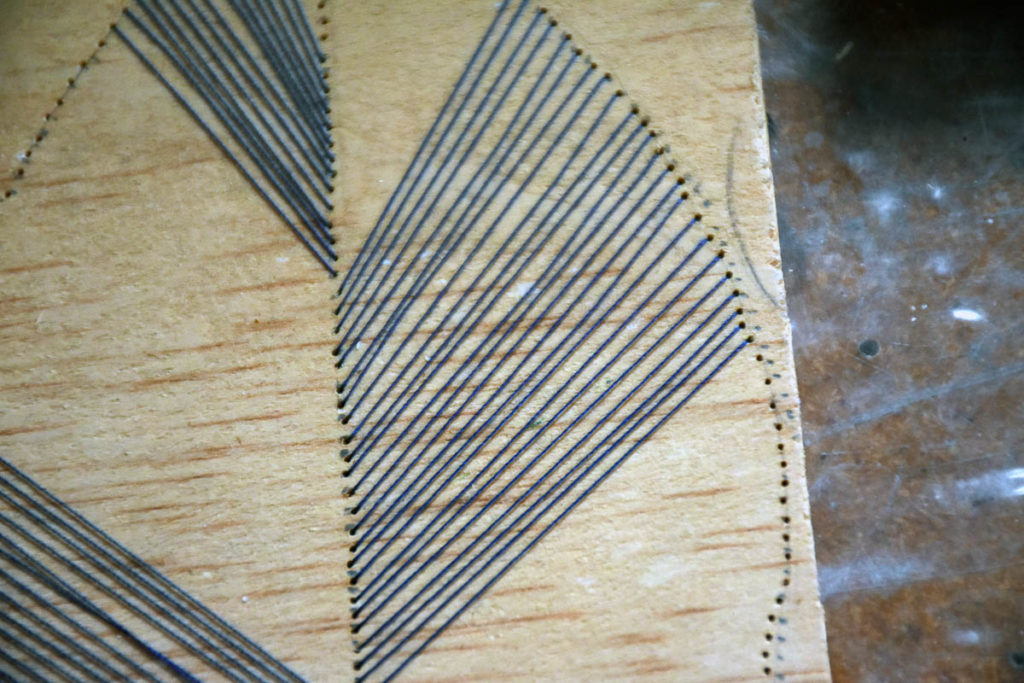

Studio preparation for a Mpavilion installation (Slow Art Collective) in 2014. The same work (below) looks completely different upon a change in context.

Mpavillion

The installation was created in 2015 whilst staying as an artist in residence in Saint Antonin Noble Val, France. During the residency, I created a large installation outside of the building as well as inside of the living space itself. Focusing on patterns of colour and light, I created the work envisaging a modernist colour field ‘painting’ rather than ‘sculpture’. Doing so, I effectively experimented with bringing a large and transparent, intangible painting in to the living room, thus transforming everyday life within the space.

Archi-loom;Summertime party

by Slow Art Collective, Arthouse, North Melbourne, 2016, photo: Eugene Howards

This version was yet another big “painting” referencing modernist colour field painting, along with the “Archi Loom”, Slow Art Collective’s staple interactive installation. A dramatic effect was achieved by setting the installation up in an historic theatre.

This shot is of the set-up and preparation for the aforementioned installation. Sometimes the process can be much more intriguing and beautiful than the finished work itself, perhaps because the process is one that is continuous and growing.

A process that is attempting to become “something” (without yet knowing what it is or is going to turn in to) in the middle of everyday life is particularly fascinating.

Intricate stitch-work on a discarded sheet of plywood. Both small and large work is of equivalent value, just as are the capillary vessels in a growing rhizome system.

This was a project I did in the small town of Boorahman. Each single strand of rope moved slowly and silently as though part of a machine.

A familiar object in an unfamiliar context. This was used for the Sensory Art Lab (by Slow Art Collective: a special commission by Abbotsford Convent) in January for C3 as part of a family program. Here, we once again relocated, this time to install on the street that is home to our studio. It was a subtle shift from everyday life to the extraordinary.

Collectivity, anonymity, process base, and improvisation are absolute core values. Craft may be a small everyday act, but once it is congregated, it too has the potential to transform into something extraordinary. It is within this very moment, I believe, that “art” is born.

Author

Born and raised in Japan, Chaco Kato has lived and studied both here in Melbourne at the Victorian College of the Arts, and internationally including Boston in the United States and in Paris, France. Chaco now resides in Belgrave, at the entrance to the Dandenong Ranges forest, about a 45-minute drive from Melbourne, Australia. Her practice traverses diverse mediums from installation to illustration; a signature form for Chaco has become her large-scale, shelter-like installations, making use of various types of string. She is the founding director (with Dylan Martorell) of Slow Art Collective, a group of artists who embrace a shared philosophy of collaboration, community engagement and sustainability. Recent commissions include installations for Mpavillion (Monash University), Wollongong art festival, Craftivism (Shepparton Art Museum) and Adelaide Fringe Festival 2019.