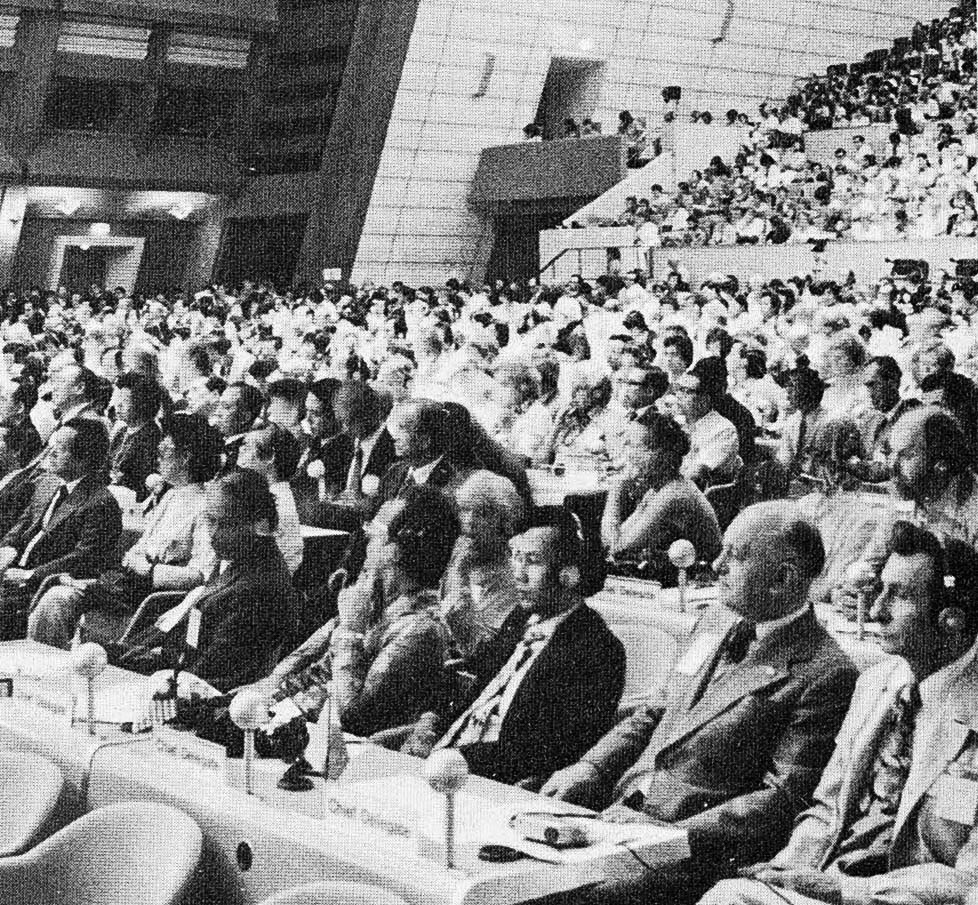

Every four years, the World Crafts Council hosts a General Assembly. In an event of Olympic scale, craftspersons from all over the world descend on a host city to exhibit their works, demonstrate techniques, sell products, talk and listen to lectures and enjoy the conviviality of a global craft community. In 1978, more than 2400 members of the craft world gathered in the city of Kyoto, including 311 from the USA, 99 Canadians, 53 Australians and 29 New Zealanders. Here we share reflections of that moment along with the keynote lecture by Yoshida Mitsukuni. Looking to the past helps us understand the future direction.

十一代長左衛門 (大樋年雄)

TOSHIO OHI CHOZAEMON XI

- Left Richard Hirsch center 14th Raku Kichizaemon and his son now 15th Raku Kichizaemon at Kyoto World Crafts Council General Assembly, 1978 (image thanks to Ohi Toshio san)

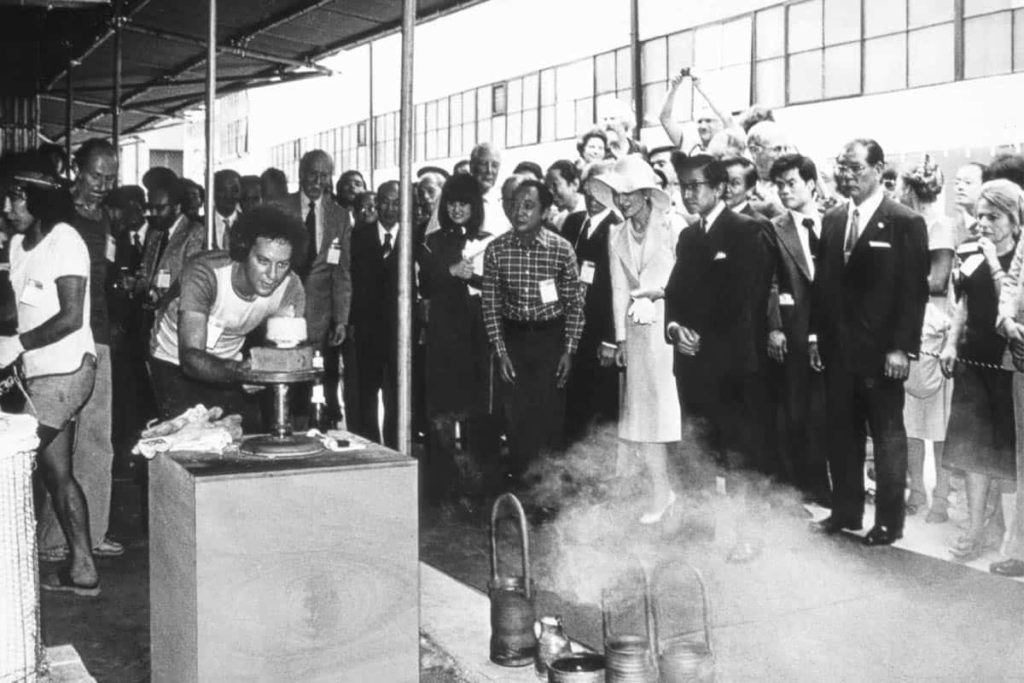

- Workshop by Richard Hirsch (left) and Kondo Yutaka on the left of the Crown Prince Akihito and Crown Princess Michiko Shōda in Kyoto World Crafts Council General Assembly, 1978 (image thanks to Ohi Toshio san)

East meets westと言う言葉は、その当時においては新しい造語であったに違いない。

米国で始まったrakuは、最先端の素材で作られた窯から釉薬が溶けた作品を一気に引き出し急冷する焼成法は、世界的に広まっていった。

このコンベンションの実行委員長を務めた近藤豊氏は、米国でrakuのパイオニア、Paul SoldnerとRichard Hirshを招くことで、世界に広まったAmerican rakuと桃山時代から茶道と共に伝わった一子相伝の楽家、楽焼が、このコンペションで、公開制作することで、東西の出会いを試みたのだった。

当時の皇太子殿下、妃殿下(現 天皇陛下、皇后妃殿下)の御成の中で、時間を超えた文化の融合は、誠に意義深いことでもあった。

私はBoston University大学院で、そのRichard Hirsch に学び、彼からこの素晴らしい出会いを伝え聞き、大切なこの瞬間の写真も授かり、今も日米で制作活動を行っている。彼に学んだ他の学生も彼を誇りとして世界中に点在しながら、このことを伝説のように語り繋いでいることだろう。

あれから40年が過ぎ、近藤豊氏、Paul Soldner氏、楽家当主は他界してしまったが、楽家は、次世代が15代当主となり、本年、更にその長男が当主16代となった。

この間、楽家や楽焼は日本の茶道精神をもとにますます深化を遂げ、米国で始まったrakuは、今やスタンダードな陶芸技術となってなり、世界各地に広まっている。

TOSHIO OHI CHOZAEMON XI

The phrase “East meets West” must have been a newly coined word at that time. Beginning in the United States, raku was rapidly spreading spread worldwide.Mr. Yutaka Kondo, who served as the executive committee of the General Assembly, invited the US pioneers of raku, Paul Soldner and Richard Hirsh. American raku spread around the world. What had evolved with the tea ceremony since the Momoyama period was now bringing East and West together.

In the presence of the Honorable Crown Prince of that time, with Imperial Princess, the fusion of culture beyond time was also truly meaningful. I studied with Richard Hirsch at Boston University Graduate School. He offered this wonderful encounter and I have photographs of this precious moment. I am still producing ceramics in Japan and the US. Other students from all over the world who learned from him and consider him a legend. Forty years have passed since then. Yutaka Kondo and Paul Soldner have passed away, but the 15th generation continued and this year, the eldest son becomes his 16th generation. In the meantime, the bonds grew deeper and deeper based on the Japanese tea ceremony spirit, and raku has now become a pottery standard and spread all over the world.

Merran Esson

- Paul Soldner, who was in his white singlet for the demonstrations but changed into a red one for the Crown Prince and Princess visit on the green carpet; photo: Merran Essen

- Visit to Shigaraki to a park where lots of clay was laid on to build with, featuring Janet Mansfield and Peter Travis; photo: Merran Essen

- The traditional Japanese Raku was the national Treasure known as Raku Kichizaemon; photo: Merran Essen

- The older gentleman is the 14th Raku teaware master and there is a younger man in the photo partly hidden by a metal pole, who is Raku Kichizaemon the 15th; photo: Merran Essen

I attended the 1978 World Crafts Council in Kyoto with my husband Michael Esson, who had graduated with a MFA in Glass from The Royal College of Art In London in 1977. American glass artist, Joel Philip Myers had seen Michael’s graduating work in London and invited him to present a talk on his glass work in Kyoto. I had been studying ceramics at Caulfield tech (1974-76) and so I attended some of the glass and ceramics events in Kyoto. I particularly remember the raku presentations with Paul Soldner; I don’t really know who the Japanese Raku master was, I always presumed that it was the National Treasure known as Raku Kichizaemon.

I somehow found myself with camera in the inner sanctum of the raku area. The Japanese presentation was peaceful and quiet, with a small ceramic container which held just one beautiful tea bowl at a time. The embers of burning sticks were placed around the kiln. On the lid, a refractory baffle constructed with air holes as air vents surrounded the kiln and the fire became quite hot. I don’t remember the firing taking too long.

The raku demonstration has remained in my memory as a very striking demonstration of what was similar and at the same time quite different. Paul Soldner prepared the work wearing a white singlet. When it was time for the Crown Prince and Princess to view this, he changed into a red singlet and took the work out of the kiln and into the post-firing reduction bin. The Japanese demonstration, on the other hand, was very calm and quiet. While the Japanese kiln was fired with wood, the Western demonstration area was noisy with gas burners and lots of flair and quite a few helpers.

One afternoon we were bussed to Shigaraki to a park where lots of clay was laid on for us the build with. I have an image of Janet Mansfield and Peter Travis, who with me, building a rather tall structure. It was a playful and quite competitive afternoon about reaching scale. I know that Les Blakeborough was also there. In the background of one of the images, there is a young Fred Olsen USA (recognised by Les Blakeborough) and I also recognise Jindra Vikova from Eastern Europe. Like most conferences, the informal events are more important than the conference proceedings: meeting and connecting with artists from all over the world.

While in Kyoto we visited the home and studio of Mutsuo Yanagihara, and one other artist who I think was Morino. Kyohei Fujita, (1921-2004) was a senior Japanese glass artist at the conference hosted a grand evening for the glass artists, he gave each of us a small glass with gold leaf decoration on it.

After the conference we visited the pottery town of Mashiko. It was not long after Shoji Hamada had passed away, and his son Yoshio Hamada who had studied glass at the Royal College of Art with my husband met us there and showed us around his fathers home and studio. We met and had tea with Mrs Hamada. We went on to stay overnight in Yoshio’s home, where we ate dinner and drank tea from Shoji Hamada bowls. Needless to say, I did not get asked to wash the dishes.

Merran Esson is an Australian artist who has been making works in clay for more than 40 years.

Yoshida Mitsukuni – Crafts and tradition

A lecture delivered at the World Crafts Council General Assembly Kyoto, 11 September 1978 (Japanese version)

The modernization of Japan began in 1860 when the Tokugawa government sent a special commission to the United States and another commission to Europe the following year to observe the workings of industrialized societies. These commissions carefully observed and investigated the various countries of the West in preparation for the industrialization of Japan. When their studies were completed the Japanese government undertook two steps: one was to invite foreign technicians to Japan and the other was to import a variety of machines and productive systems. The primary motivation behind the development of industry at this period in Japanese history was to build up enough military power to protect Japan against the rapid American and European invasion of Asia.

This policy was continued by the new Japanese government after the Meiji Restoration in 1868. The new government was anxious to industrialize and to adopt the European and American systems of government and economy of the 19th century. Many foreigners were invited to help complete the process as soon as possible. In 1873 the governmental agencies had 507 foreigners and private agencies had 73. In 1893 the former had 104 and the latter 538. Sixty to seventy per cent of these people were technicians and teachers. Thus, with the help of many foreign engineers, the government started to build railroads, telephone and telegraph networks, buildings, lighthouses, etc.

In 1873 the Governmental Industry Board was established to start government-managed industries such as mining, metallurgy and shipbuilding, importing all the necessary industrial plants. In 1877 the Imperial College of Engineering was founded to train senior engineers. It was a completely new type of engineering college unknown even in Europe, with a curriculum made by Henry Dyer, an Englishman. The Industry Board became the center for the introduction of modern technology into Japan.

In 1871 the Meiji government sent a commission to Europe which reconfirmed the importance of industrialization. As soon as the commission returned to Japan a Ministry of Home Affairs was established to carry out a new modernization policy. While the Industry Board tried to directly import and transplant modern technology, the Ministry of Home Affairs set as its goal the modernization of agriculture, stock-farming and the silk and cotton industry. The silk and cotton industry had reached a high level of handcraft during the 18th and 19th centuries in Japan. Silk was produced in Kyoto and other regions, and cotton in Northern Kyushu, along the coast of the Seto Inland Sea, in Osaka, in Edo and in Nagoya, each region having its own unique designs and patterns.

However, these silk and cotton goods were not good enough for export in terms of quality and design, so the government introduced French technology for silk and English technology for cotton in an effort to improve their quality. At the same time, the use of steam engines was introduced into the handcraft industry and the scale of management was expanded.

This government-initiated industrialization policy is in effect even now. From around 1880 increasing private capital brought about the growth of private industries, but whenever new technology was introduced, strong leadership and financial support were in the hands of the government. Examples of this are seen in the iron, shipbuilding, chemical and electric industries, as well as in agriculture and fishery.

In any case, until 1940, Japanese industrialization always aimed for the development of export-oriented industries and of the military industry in order to compete with the powerful nations of Europe and America.

For this reason, most daily goods continued to be manufactured by handcraft methods developed in the Edo period. It was not until after 1950 that Japanese daily goods came to be made by modern machines. Here lies the main reason for the continuity of Japanese craftsmanship in handcrafts from the 18th century to the 20th century. The reorganization and expansion of these handcrafts, such as of silk, cotton and ceramics, made possible their export in enormous quantities by 1940. This served to instill Japanese craftsmen with a strong sense of pride in being the formers, keepers and leaders of the Japanese way of life, and producers of goods exported for the prosperity of Japan.

Here we must stop to consider the historical character of the Japanese handcrafts which have managed to survive until this day.

Before industrialization, Japan’s economy was naturally based upon agriculture, later supplemented by manual labor. Handcrafts survived through these two mediums. The main crop in Japanese agriculture is paddy rice. The cultivation of rice in paddies necessarily involves the cooperation of many people and because of this cooperation, Japanese villages came to be strongly community oriented. During the Edo period, each feudal lord established a closed economic system within his fief resembling a small independent country. When the economy seemed in danger of declining each lord tried to improve the situation by developing unique handcraft goods to sell to other regions. Most of the traditional industries of districts of modern Japan have this kind of historical background in the development of their local handcraft.

The handcrafts of an agricultural society aimed to be self-sufficient using local materials and producing items that would meet the needs of a particular area.

Japan has a north-south elongated shape which meant that the way of life differed considerably according to the location of each community. This meant that agricultural and organisational systems differed also. Hence, locally produced goods had different functions and designs. The most important aim, however, was for the handcraft items to be suitable for daily usage in other areas. Functionalism was the major characteristic of handcraft goods made in an agricultural society.

Another aspect of Japanese handcrafts is to be seen in the cities of Japan. In the eighteenth century, Japan had large cities rarely found in other parts of the world. Edo, the political center, had a population of one million, while Osaka and Kyoto had about 350,000 people. Moreover, Japan was completely closed to the world for 300 years through the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, the only exceptions being China, Korea and Holland. Because of this the influence from Europe, culturally so different, was small and these large cities developed their own closed culture cr resembling small villages. One of the elements of such closed cultures was the development of urban handcrafts to provide the cities with the necessary daily goods.

Japanese cities were composed of the governing samurai, merchants and craftsmen. Of the three major cities, Kyoto had a very special character. Kyoto had been the capital of Japan since 794 and the presence of the emperor, even after the actual political power had moved to the east, preserved its status as the formal capital. For this reason, a life centered around the court managed to survive despite many changes in the nation. The many shrines and temples in Kyoto also have made it the religious center of Japan.

Court life consisted of a kind of drama resembling its counterparts in Europe. The use of beautiful things, elegant manners, witty conversation, gorgeous ceremonies and parades, etc. required a great assortment of different kinds of goods. Craftsmen strived to produce even more beautiful and elaborate things in response to this need. They aimed for beauty and refinement.

The Engishiki (a collection of the rules and code of the early Heian period, completed in 927 in 50 volumes) is a historical documentation of the systems of craft production in Kyoto during the 10th century. According to this record, all production was divided into specialist areas. Workers were paid in rice and salt by the day. Working hours varied according to the season, differing in spring and summer when the days are long and in the autumn and winter when days are short. Since the daily production requirements were seldom heavy craftsmen were free to pursue perfection in their works. For example, in the case of paper production, the raw material, the bark of trees, was collected as a tax from all over the country. Most of the paper production was done in Kyoto. The amount of paper required at the Kamiyain (paper mill) was 20,000 sheets (20 by 12 inches). During the spring and summer, 190 sheets were required daily. Besides this, set amounts of paper were collected from various areas all over Japan.

In the case of the production of bronze mirrors, it was calculated that the labor of 22 persons (2 for casting, 18 polishing, 2 helping) was required for the production of one seven inch square mirror.

To make an official’s unlined clothing the labor of one and one-third persons was considered necessary.

It was with such careful organization that the goods needed for the court and government agencies were produced. This was extended to other fields as well, such as metalwork, woodwork, lacquer and leatherwork. Each craft sought beauty and refinement.

Simultaneous with this local production was the importation of goods from China. Chinese goods, known as Karamono (goods of Tang), were treasured in the court. The crafts of the Tang and Sung eras were especially famous for their high level of excellence. Learning from these Chinese works the craftsmen of Kyoto worked to improve their techniques.

In 894, however, Japan stopped sending regular missions to China resulting in the development of unique Japanese designs and forms. These formed the main stream of Japanese urban crafts and developed into an art giving beauty and taste to the daily life of the city. Here was the appearance of a new type of handcraft which often put more value on beauty than functionality.

This tendency became stronger in the seventeenth century as Japanese society stabilized under the feudal system. Many local castle-towns came into existence in addition to the cities of Edo, the political center, Kyoto, the cultural center, and Osaka, the commercial center. These smaller cities or towns developed their own handcrafts.

Each city usually had a community of craftsmen living in a designated area. This phenomenon can be seen in Kyoto even now. Nishijin is the largest center in the world of silk goods manufacturers. In the south of the city is another community of potters around Higashiyama-Gojo. Woodwork and furniture makers have their homes and shops on Ebisugawa Street.

Most of these handcrafts have a system of division of labor similar to that recorded in the Engishiki The division of labor is finely delineated down to very detailed processes and each process has its own professional worker who is highly skilled. This is especially clear in Kyoto where the tradition of government-managed handcraft has survived. Until Japan industrialized Kyoto was the largest handcraft center in the country.

What is the philosophy of the Japanese people who have preserved handcraft techniques and designs for over one thousand years? The Japanese way of thought owes its logical aspects to Confucianism which was established in China around 400 B.C. One of the classics of Confucian teaching is the Chouli which has a chapter, Kaogongkong, known as the oldest book on technology in China. When we compare this with the book on architecture written by Vitruvius around 25 B.C. in Rome, we find a big difference in the philosophies of technology of East and West.

In the Kaogongkong we find two main points. One is the distinction made between creating and producing; that is, wise men create and craftsmen transmit the technique. The second consists of four conditions necessary for producing perfect goods: 1. proper season, 2. ideal surroundings, 3. good quality materials, and 4. highly skilled craftsmen. The Japanese added another condition to this — good tools. Dogu, the word for tools, originally came from Buddhism where it meant things necessary for Buddhist training. The word later developed to include tools for crafts. Giving tools spiritual value is characteristic of Japanese handcrafts. When we examine the tools of Japanese workers we find them inscribed with the dates on which they were first used. That is the day when the craftsman and the tool were united, bringing the tool to life. This unity, however, is achieved only between the tool and its owner. Hence, one can not use another’s tools. Tools should not be used on New Year’s Day and before a worker’s guardian diety’s day and before use a prayer of thanks should always be given. After many years of repeating such ceremonies there comes a day when a tool is too old to be used. The user buries it with dignity at which point the tool ceases to exist. Tools lived and died — their role was important in the Japanese philosophy of technology.

Based on this philosophy, Japanese designs also have developed their own esthetics. The first is the unity of man and nature. Nature does not exclude man. Man and nature are each of one universe and between them there is rapport and sympathy; man can become a part of nature. Man can also reconstruct nature around himself. Thus many craft designs seek to reconstruct nature in landscape scenes. The change of seasons can be expressed nicely in scenery designs. To symbolize the seasons many plants were used, such as camelias and cheery blossoms for spring and water plants for summer. Designs should not only reconstruct nature around man, but at the same time, they should give the user of the item a special sense of time and space. In order to achieve this themes from Japanese classical literature were often employed. Sometimes Chinese literature and history were used. These designs gave people a free literary image. Literary designs are a major characteristic of Japanese traditional designs. They can be compared with European designs of Greek mythology, the Old Testament, and Homer’s works found in tapestries. However, Japanese designs differ from those of Europe in one respect—while European designs are realistic, Japanese are symbolic. When Japanese people see a pattern of irises in a river they are immediately reminded of a classic love story. Of landscape scenes, the seasons, literary and other design motifs non-realistic, symbolic designs are regarded as the best.

When industrialization started in the middle of the 19th century, European and American concepts of art were introduced into Japan: Their idea of art can be summarized as the free expression of individuals pursuing beauty in their own way. In the world of Japanese handcrafts there had been a custom, since the 11th century, of the master of a workshop putting his name on all the works produced there whether he had made them himself or not. This was done in all sorts of craft fields such as Buddhist sculpture, arms, pottery, lacquerware, etc. It was meant to show an accepting of responsibility for the quality of the work. In contrast to this, the use of signatures in the Western world of fine arts was to show individuality. These two systems have become confused in Japan since the 19th century as the European idea of expressing one’s individuality becomes more popular in art fields.

In early modern Japan, art was limited to painting and sculpture as it was in the West. Despite this, the Japanese tradition of urban handcrafts expanded in the 18th and 19th centuries and survived industrialization. The beauty- oriented crafts had a strong claim to being considered as an art. At last in 1927, in a government-sponsored art exhibition, an independent section for craft was established, giving crafts a citizenship in the world of art.

Even though Western ways of life came to Japan with industrialization handcrafts continued to provide daily goods, as I have noted before. Many of them are still active as traditional industries. Japanese people have managed to achieve a way of life which is western in public spaces and Japanese in private spaces. Handcrafts have survived to fill the private space. The continuation of Japanese ways in this private space has allowed the Japanese performing arts to exist as they were before industrialization. Noh, Kyogen, Kabuki, classical dance, tea ceremony and flower arranging all have need of superior quality craftworks. Needless to say, traditional designs and techniques are employed by independent, professional craftsmen for the production of these works.

Religious goods have also continued to be manufactured in this fashion. The Japanese way of life seems so westernized, but many things from the pre-industrialized era are still in active use in private life-giving Japanese crafts an important part to play.

An industrialized society is one in which all manufacturing systems are industrialized and mechanized. Japan, however, has realized industrialization retaining both individual and industrial crafts as parts of a modern cultural network. Of course, there have been many contradictions and conflicts, but efforts to solve these problems will lead to the solution of many problems of modern culture the world over. Proper recognition of the homogeneity and heterogeneity of crafts in the world can lead to mutual understanding between various countries. The Japanese situation is a source of clues for other peoples of the world.

Author

The late Yoshida Mitsukuni was a distinguished author of many books on Japanese culture, including, The Culture of Anima: Supernature in Japanese Life (1985), The people’s culture, from Kyoto to Edo (1986), Naorai: Communion of the Table (1989) and Tsu Ku Ru: Aesthetics at Work (1990

The late Yoshida Mitsukuni was a distinguished author of many books on Japanese culture, including, The Culture of Anima: Supernature in Japanese Life (1985), The people’s culture, from Kyoto to Edo (1986), Naorai: Communion of the Table (1989) and Tsu Ku Ru: Aesthetics at Work (1990