In her career as a museum curator, Christina Sumner helped reveal to the world the splendour of Central Asian crafts. Here she retraces her journey as she sought permission to borrow their priceless treasures.

A small plate with an enchanting hand-painted image of springtime love hangs on my kitchen wall. It catches the light. One of the lovers wears the traditional chapan and doppa (coat and skull cap) of an Uzbek man; above them is a branch laden with almond blossom. The plate was a gift from the director of Tashkent’s Applied Arts Museum, in honour of our excited agreement to collaborate on an exhibition project. It conjures up happy memories of my travels in Central Asia, the warmth of its people and the beauty of its diverse traditional arts.

A small plate with an enchanting hand-painted image of springtime love hangs on my kitchen wall. It catches the light. One of the lovers wears the traditional chapan and doppa (coat and skull cap) of an Uzbek man; above them is a branch laden with almond blossom. The plate was a gift from the director of Tashkent’s Applied Arts Museum, in honour of our excited agreement to collaborate on an exhibition project. It conjures up happy memories of my travels in Central Asia, the warmth of its people and the beauty of its diverse traditional arts.

Plate, Uzbekistan, 2002, hand-painted earthenware, 20 x 2.5 cm. Photo Christina Sumner

This brief account reflects two decades of professional engagement with Central Asia, and its textiles in particular, and of the luck involved and hurdles encountered when endeavouring to develop a collaborative curatorial project there, soon after the breakup of the Soviet Union. It also tells of the richness and diversity of Central Asian arts as well as some of the kindred spirits I met and the many memorable experiences that affirmed my love affair with the region.

In 1999 I curated an exhibition for the Powerhouse Museum’s recently-established Asian Gallery; titled Beyond the Silk Road: arts of Central Asia, the objects were almost all drawn from the Museum’s own collection. My curiosity about Central Asia and a desire to understand this tantalising and little-known region and its gorgeous crafts had been germinating for a while. I knew the lush nomadic Turkmen and Baluchi rugs and trappings of the region, and proudly owned some modest examples. And in 1992 I had seen an exhibition of suzanis, the beautiful dowry embroideries from urban western Central Asia, here in Sydney. Undoubtedly among the world’s most spectacular traditional textiles, these were an inspiration and the Museum was persuaded to acquire a fine example for the collection.

In Beyond the Silk Road and the catalogue of the same name, we wanted to make sense of the beautifully crafted Central Asian objects in the Museum collection and tell something of the cultures that generated them. The narrative I eventually chose explored the symbiotic relationship between the ethnically distinct nomadic and settled peoples of the Central Asian region, an appreciation of which I felt (and still do) was basic to understanding both the area and its crafts.

The Silk Roads

The Silk Road, or Roads, as that network of caravan trade routes is more correctly described, criss-crossed Central Asia and linked China with the Mediterranean. From at least the second century BCE through to the fifteenth century CE, landlocked Central Asia was the bartering heart of a complex phenomenon which still captivates us today. Facilitating this trade through the centuries were the people of Central Asia, who can be broadly described as having followed either a pastoral nomadic or settled agricultural way of life, a distinction that was both ethnically and geographically determined. Nomads guided the caravans through desert, mountain pass and steppeland, which was best suited to seasonal grazing, while merchants thronged the fertile oases that supported agriculture and a settled urban life.

The nomad versus farmer duality was complex however as, while distinct, these modes of subsistence were always interdependent. The capacity of the steppes to support the tribes was limited and, under pressure, nomadic people sometimes moved into agricultural areas and turned to farming, whereas farmers often took their animals up into the hills. Nomad and farmer depended on each other to provide what their own way of life could not: nomads traded their meat, horses, wool and carpets for the grains and fruit as well as cotton and silk of the oases dwellers. Significantly, the distinction between nomadic and settled ways of life is also clearly reflected in their material culture.

The 1920s witnessed the end of Russia’s Tsarist rule and the beginning of the Soviet era when today’s five Central Asian states, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan were created along ethno-linguistic lines. Four were named for people of nomadic origin—the Kazakhs, Kyrgyz, Turkmen and Uzbeks—who speak Turkic languages; the Tajiks of Tajikistan however speak a language related to Persian. While the Kazakhs, Kyrgyz and Turkmen basically retained their nomadic lifestyles and their characteristic nomadic craft traditions, most Uzbeks settled down in the sixteenth century and formed an urban culture in collaboration with the sedentary Tajiks. Soviet policies brought about massive environmental damage in western Central Asia however; failed attempts were made to turn committed pastoralists into farmers, while establishing cotton as Uzbekistan’s major crop caused catastrophic shrinking of the Aral Sea. Collectivisation and anti-Islamic policies combined to devalue the traditional lifestyles of both nomadic and settled populations.

The eventual break-up of the Soviet Union and the emergence of the independent nations of Central Asia in the early 1990s gave rise to a heady upsurge of nationalistic fervour, the principal icons of which have been their traditional crafts. It was an exhilarating decade, filled with possibility as the newly-liberated ex-Soviet states assessed their resources and opened their doors to new alliances and foreign investment. Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan had oil and gas reserves, Kyrgyzstan had lakes and mountains, Tajikistan had precious metals and water. All five new nations have been eager to encourage international investment and tourism and set about marketing themselves in English as well as Russian. A growing emphasis was placed on their long-suppressed traditional cultures, which encouraged a renewed interest in traditional crafts and skills.

Nomadic and urban, wool and cotton

- Yurt camp, Kyzyl Kum desert, Karakalpakstan, April 2015. Photo Christina Sumner

- Tashkent Applied Arts Museum, 2003, carved and painted plaster (ganch) facade. Photo Christina Sumner

- Ulugbeg Madrassa, the Registan, Samarkand, early 1400s. Photo Christina Sumner

The distinction between the material culture of nomadic and settled peoples is clear. In particular, their traditional textiles are quite different in materials, structure and design. The nomadic lifestyle, which required seasonal migrations over vast areas in search of grazing, necessitated horses and camels for transport plus a portable home and the traditional felt tent or yurt was quick to erect and dismantle. Richly ornamental bags, carpets and cushions for transporting and storing goods, as well as providing warmth and comfort, were woven by the women of the tribe from the wool of their animals; these have long been highly desirable collectibles. Different tribal groups ornamented their weavings with their own distinctive patterns and motifs which were memorised by the women and passed down the generations.

Today, very few people still subsist by following the traditional nomadic lifestyle, but the inheritors of nomadic traditions hold them fiercely close, and the yurt in particular can still be seen in town gardens, as workers’ huts on the side of the road, on primary display in museums, as accommodation for tourists, and as an evocative symbol on the flag of modern Kyrgyzstan. Interestingly, efforts are now under way to restore nomadism in Kyrgyzstan as a response to the negative effects of climate change.

Settled communities, on the other hand, live in villages, towns and cities, fence their fields and practise agriculture. The textiles and clothing produced in urban centres differ fundamentally in form from those produced by nomadic groups. To ornament their homes, they produced a wide range of silk-embroidered cotton curtains, covers and hangings which tend to be more delicate and lighter in colour than the rich dark woollen carpets, furnishings and trappings of the nomad women. Around the oasis towns of Central Asia, cotton farming was of major economic importance and took up a large proportion of arable land; surrounding each cotton field were mulberry trees, whose leaves were essential to feed silkworms. Living in permanent homes as they did, the creativity of the urban people of Central Asia was not limited by scale or the unavailability of materials. They produced superb crafts such as gold embroidery, decorative metalwork, carved plaster, ceramics and woodwork, as well as suzanis and monumental architecture.

Despite the erosion of the nomadic way of life through confiscation of land, growing urbanisation and materialism, and despite seventy years of Soviet collectivisation, the distinction between the material culture of nomads and oasis dwellers is lasting and their differing crafts contribute substantially to the treasures that lure today’s travellers to the region.

“You should go.”

- Kygyz women and elechek demonstration in yurt, Bishkek, April 2016. Photo Christina Sumner

- Bactigul Assmalieva, demonstrating ala-kiz, Kyrgyzstan, April 2016. Photo Christina Sumner

- Bactigul Assamalieva, demonstrating shyrdak, Kyrgyzstan, April 2016. Photo Christina Sumner

Once Beyond the Silk Road was open, I kept very quiet about having never actually been to Central Asia, well aware that this might well have coloured my interpretive perspective and feeling apologetic when obliged to confess. The stars aligned however when I was introduced to Guy Petherbridge, a conservator and cultural heritage authority. A visitor to the exhibition, he was working with AusHeritage in collaboration with UNESCO in Tashkent to develop a cultural heritage management plan for Central Asia. “You should go”, said Guy. The Museum generously funded me on what was an exhilarating, AusHeritage and UNESCO-facilitated journey through four of the ‘Stans: Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. Guy travelled with me and became an integral and indispensable colleague in what lay ahead.

By the time I reached Tashkent, the capital of Uzbekistan, around 3am one morning in October 1999, the Soviet Union was no more and the Central Asian republics had been exploring their newfound independence for a mere eight years. Inevitably, the culture that greeted me in Uzbekistan was still strongly Russian. In the as-yet unrenovated Tashkent Hotel where I stayed, each floor was controlled by a Russian “floor lady”; mine was large and intimidating, making it clear I should change money only with her, and immediately. Risking her ire, this was achieved the next day however, on the advice of my UNESCO contacts, and provided me with with bundles of Uzbek sum in two plastic bags. At that time, I was informed, only the British ambassador changed money at the official rate.

So began the first of seven journeys to Central Asia, a place I came to love. Four were directly related to my curatorial work at the Powerhouse Museum and three, over a decade later, leading groups of travellers keen to explore and learn about Central Asia. In October 1999, I was fresh from Beyond the Silk Road, keen to establish professional contacts, primed for the adventure of it all, optimistic about possibilities and happily unaware of the turbulent politics and shifting allegiances that would regularly confound me. I spoke none of the Central Asian languages and no Russian, and although some of the people I met spoke English, most conversations were conducted through an interpreter and trust, therefore, became a critical factor in the many many meetings and discussions that arose.

It was evident very soon after my arrival in Tashkent that I was viewed by the UNESCO office as an expert in all things museological, a resource to be tapped, rather than the curious traveller I believed myself to be. I had to gather my wits and remember all I had learned in my 14 years at the Powerhouse, which fortuitously included the intensive development process of the 1980s. A brilliant, whirlwind itinerary through Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan was skilfully mapped out for us by UNESCO staff, who provided essential practical assistance with travel logistics and introductions to key museum and cultural heritage management personnel. (Visiting Turkmenistan would have to wait until I led tours there in 2014 and 2016).

Our tour included pivotal visits to several state museums which, to their credit, had been established by the Soviets. I was granted access to outstanding collections in Tashkent, Bukhara and Samarkand in Uzbekistan, Nukus in Karakalpakstan, Bishkek in Kyrgyzstan, Almaty in Kazakhstan and Dushanbe in Tajikistan. Speechless with wonder at the textiles in particular, the purpose of the journey and the question of how to choose the focus for a possible collaborative project occupied my thoughts in brief moments of respite. I wanted to see and evaluate collections, observe local museological practices, and begin to forge professional relationships with senior museum staff. I wanted to establish collaborative programs with Central Asia which would not only enhance the Powerhouse’s international profile, but offer opportunities for staff development in both directions. In that post-Soviet era, Central Asia was beginning to open up to the wider world, and its museums were keen to form affiliations with institutions such as the Powerhouse. My list of desirable outcomes was long, and with more experience of the region and hindsight, it was somewhat overly ambitious.

Suzanis, chemical weapons, vodka and limousines

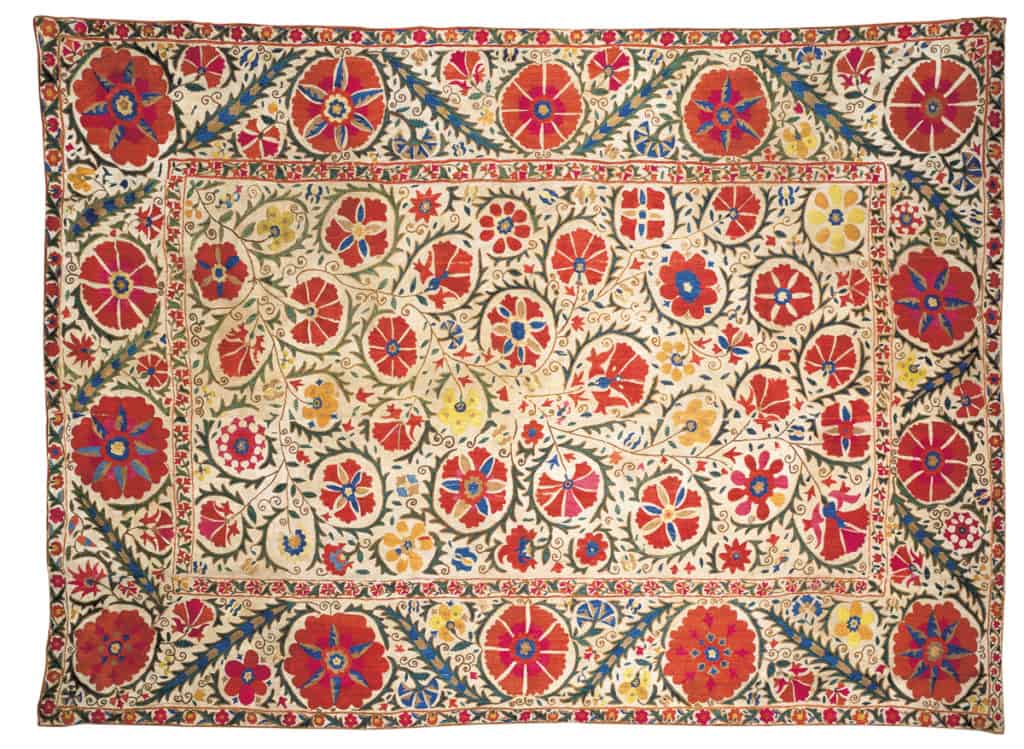

- Bukhara suzani, early to mid 1800s, silk couching and chain stitch on cotton, 234 x 173 cm. Powerhouse Museum collection

- Shakhrisabz suzani, 1900-1910, silk chain stitch on cotton, 235 x 216 cm. Samarkand State Museum collection

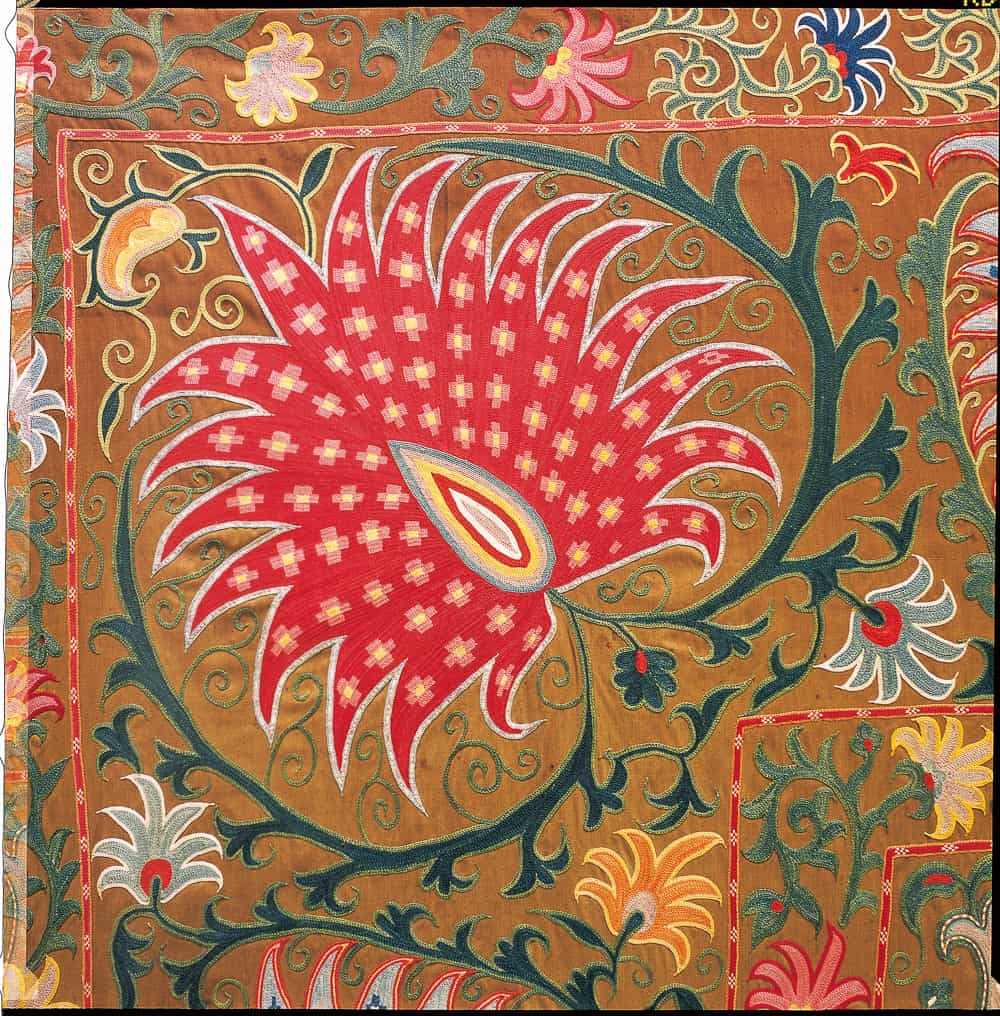

- Shakhrisabz suzani (detail), 1900-1910, silk chain stitch on cotton, 235 x 216 cm. Samarkand State Museum collection

- Bukhara suzani, late 1800s, silk and wool chain stitch on silk, Samarkand State Museum collection

- Bukhara suzani, late 1800s, silk chain stitch on cotton, 253 x 148 cm. Samarkand State Museum collection

- Shakhrisabz suzani (detail), late 1800s, silk chain stitch on cotton, 235 x 169 cm. Bukhara State Museum collection

- Tashkent palyak (detail), late 1800s, silk couching and chain stitch on cotton, Tashkent Applied Arts Museum collection

- Karakalpak older woman’s robe or ak jegde, silk embroidery on cotton, ca 1900, Savitsky Museum collection, Nukus.

Traditional textiles and textile technology are at the heart of my own specialist knowledge, and visits to state museums in Uzbekistan and Tajikistan brought unparalleled opportunities to see a matchless range of my beloved suzanis. Suzani is a generic term, from Persian suzan meaning needlework, that covers the wide range of domestic textiles that were stitched for a young girl’s dowry by the women of her family. They included wall hangings, bed covers and sheets, pillow covers, prayer mats, niche curtains, table and cradle covers and a variety of bags. Traditionally constructed from narrow strips of handwoven cotton and embroidered with brightly coloured silks, their mostly floral patterns were characteristic to different regions of the country and often rich with symbolic meanings. When they married, which was often very young, girls left their own homes and went to live with their new husbands, often a long way away; the suzanis they took with them were saturated with love and well wishes from the women who stitched them, for good health, prosperity, safety and fertility. I knew a display of these would make a fabulous exhibition.

Also on my itinerary was a visit to Nukus in Karakalpakstan, an autonomous region in northwest Uzbekistan. We flew to Urgench in a huge ex-army Ilyushin, full of workers in kerchiefs with baskets of chickens, which trundled into Tashkent from the east and was heading west. From Urgench we drove to Khiva along an immensely straight road bordered by rice and cotton fields. Khiva is tan-coloured mud brick, a lovely if sanitised museum city whose streets are swept clean in the dawn light each morning. Remote Nukus however, our actual destination, is modern and generally unhealthy, seen by the Soviets as the ideal place to test chemical weapons, many of which were buried on an island in the nearby Aral Sea.

In Nukus however is the Savitsky Museum whose three outstanding collections were assembled in the early 1900s by Russian artist Igor Savitsky: a Karakalpak ethnographic collection, archaeological material from the region, and a matchless collection of Russian avant garde paintings. In 1999, these were housed in two old buildings while the new museum was still under construction. There were, however, no funds and no planned sequence for completion. UNESCO saw assistance for Nukus as a priority and my counsel as visiting expert—in museum architecture, conservation, storage and climate control, etc.—was requested. This was challenging to say the least! Safely back in Tashkent, we agreed that a project manager and a donor scheme to finance the project were essential. We encouraged the director Marinika Babanazarova (with whom I became friends and visited in subsequent years), to focus on how to use the space and, back in Australia, I solicited the advice of a leading museum architect. Since then, in recognition of the Savitsky collections, much has changed and two more buildings are now being erected. The Karakalpak ethnographic collection had particularly attracted me as an exhibition possibility, if these gorgeous treasures could be made available for loan to Australia.

Hospitality is sacred as well as warm in Central Asia, and before leaving Urgench we were treated to a banquet, hosted by the Karakalpak Minister for Culture. Our flight departure time came and went with no sign of our host releasing us until, with a last vodka toast to our future collaboration, we piled into a convoy of black limousines which drove us straight onto the runway and up to the waiting aircraft. The Minister himself carried my suitcase up the stairs.

Museum staff in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan were also welcoming, showing us their collections and willing to establish contacts for future collaboration. In the following year I was invited back to Almaty to take part in a UNESCO-sponsored workshop to help train Kazakh museum staff in using a new collection management database. Two days in Kyrgyzstan enabled me to visit Bishkek’s superb History Museum where there was a display of traditional and contemporary felts. I was struck by the artistic quality and contemporary feel of these Kyrgyz felts and in the basement they showed me huge rollers on which were stored an amazing collection of large patterned felts. These too were bursting with potential to form a stunning exhibition. Visiting marginalised Tajikistan was not so straightforward, but our welcome was equally warm and we were shown their wonderful ethnographic collection which included some very fine suzanis. In the end, to get to Dushanbe, we were embedded in a UN business delegation and travelled in style in another convoy of black limousines.

Thanks to UNESCO, I left after that intoxicating first visit having seen more and with more insights than I could have imagined, and having met and begun to establish relationships with key individuals. These initial encounters, both planned and by chance, helped inform the decision I later made to propose a collaborative exhibition project based on dowry embroideries and glazed ceramics, rather than the Karakalpak ethnographic collection or the Kyrgyz felts.

How to get a presidential decree

The eventual outcome was, after four hectic visits, complicated negotiations and political shenanigans, the exhibition Bright Flowers: Textiles and Ceramics of Central Asia, which opened in the Powerhouse in 2004. This was co-curated by Guy Petherbridge, who managed the ceramics as well as offering wise strategic advice throughout. Almost all of the objects we eventually displayed were on loan from Central Asian state museum collections. I now know this was a one-off occurrence and thanks are due to tolerant colleagues in both Australia and Central Asia who supported the project, to my own naivety about the roadblocks we would have to navigate, together with some fortunate timing, and serendipity.

The development of Bright Flowers turned out to be complex and convoluted, for a range of practical and political reasons. Fortunately I worked this out only once it was too late to beat a hasty retreat! Luck played its mysterious part. For example, when I shared a taxi with a cultural attaché on my first visit and spoke of my proposal to develop a collaborative exhibition, she commented that I would have to convince Professor Naguib Khabibullaev, director of Tashkent’s exquisitely painted Timurid Museum and president of ICOM Uzbekistan. It turned out that the Professor was also unusually close to the then President of Uzbekistan, Islam Karimov. Only later did I learn that Karimov’s reputation for human rights abuse was dire and his authority and power were more or less absolute in Uzbekistan; expressions of dissatisfaction with his regime were quickly silenced. Eventually in 2004, Professor Khabibullaev took on the role of courier, which enabled Mrs Khabibullaev to travel with him and go shopping in Sydney.

It turned out that to borrow from Uzbek state collections required a presidential decree which, I was informed, would take three years at the very least. However the Australian ambassador to Russia had just arrived in Tashkent to present his credentials to President Karimov and to discuss Australian interests in Uzbekistan. Unbeknown to me, these interests included my project, which a researcher for the ambassador had found in an AusHeritage report. Serendipity was working for us again, as the story goes that Karimov nodded and said “Let me know if you need any help.” Thanks to the ambassador’s visit and Professor Khabibullaev’s influence, unbelievably we got our presidential decree without delay.

The road to achieving the Bright Flowers exhibition was littered with hurdles, as well as a fantastic journey. In beautiful historic Bukhara, I met Dr Koryogdi Jumaev, curator at the Summer Palace Museum. Although we had no shared language, we communicated perfectly easily through the suzanis we both loved. During my fourth visit to Bukhara, having finally gained permission from Tashkent authorities to select loans from the Bukhara collection, the museum director, seemingly determined to foil Tashkent, told me sadly that the lighting had failed and I wouldn’t be able to see the collection after all. Never travelling without a torch, I pulled a Maglite out of my bag and said “It’s all right, I have a torch”, at which point Koryogdi grabbed it and, knowing exactly where to find the suzanis he wanted with the aid of the Maglite, brought treasure after treasure out into the light of day. Eventually we borrowed several of those breathtaking embroideries for display.

As a frequent traveller in Central Asia, whether following the paths of nomads or Silk Roads traders as a harried but determined curator, innocent bystander or tour leader, Central Asian hospitality has always been a delight as well as a point of honour. Many are the cups of tea I’ve drunk and many the vodka toasts reciprocated; friendships made over twenty years ago have stood the test of time and distance. In Tashkent, the outstanding potters Akhbar and Alisher Rakhimov have always welcomed my tour groups warmly to their studio, while Koryogdi also remains a dear friend. Both the Rakhimovs and Koryogdi were significant collaborators for Bright Flowers and wrote fine pieces for the catalogue.

Silk Roads become Belt and Road

Bukhara suzani comes out into the light, late 1800s, silk chain stitch on cotton, 271 x 192 cm. Bukhara State Museum collection

In 2014 I was invited to lead a tour group to Central Asia and leapt at the opportunity of returning to Uzbekistan in a different role, and to visiting Turkmenistan for the first time. In 2016 I returned to Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan with a tour group. While placing a focus on seeing Central Asia’s beautiful crafts, it was equally important to me to locate them within their cultural and historical context, to ensure that newcomers to the region gained insights into its significance and allure. People choose craft-oriented travel for different reasons. Some are motivated by a love of beautiful and exotic objects and seek to encounter them in their homeland; craft practitioners with professional interest in the processes of making, particularly practices akin to their own, seek engagement with other practitioners in other places; these encounters have the potential to be inspirational as people take back images and ideas and incorporate them in their own practice. Some travellers are passionate collectors or traders, others happy with keepsakes and souvenirs. The purchases people take home from craft tours serve as both visual delights and mnemonics, evidence of an enquiring spirit and their creative wanderlust.

Over the past six or seven decades, global tourism has increased exponentially to become one of the world’s fastest growing economic sectors. Additionally, it has become increasingly diversified and a principal source of income for many developing countries, including Central Asia. Cultural tourism, a subset of which is craft tourism, is focused on an interest in the culture of a country or geographical area, including its history, the lifestyle of the people who live there, and the art, architecture, religion and other factors that shape their lives. In Central Asia, governments are aspiring to stimulate their tourism sectors and have invested substantially in the rebuilding and renovation of their historic Silk Road cities. In 2017, opportunities for collaboration and future partnerships were discussed to establish a common and resilient Central Asian destination under the shared “Silk Road” brand.

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is a massive global strategy to resurrect the ancient Silk Roads. “Belt” refers to the Silk Road Economic Belt, featuring land routes through Central Asia to Europe, while “Road” somewhat confusingly refers to the twenty-first century Maritime Silk Road, including the sea routes connecting Chinese ports to Europe and the South Pacific. One of President Xi’s most ambitious policies, it involves infrastructure development and investment in some 150 countries. Promoted by the Chinese as a wish to improve how they are connected globally, a bid to improve China’s connectivity with the rest of the world, others view the BRI more as a bid for Chinese dominance in global affairs through a China-centred trading network. The countries signed up to it cover approximately half the world’s population and about 30% of the world’s economy and include Central Asia, but not yet Australia.

Craft tourism in Central Asia is inevitably grounded in the lure and history of the ancient Silk Roads and its architectural marvels, but relies also on the contemporary, on its vibrant and colourful arts, crafts and folk cultures. These are of central importance to sustaining both culture and economy, as well as providing experiences for travellers and employment for artisans who are preserving cultural heritage as well as generating income. Sponsored by the UN World Tourism Org and UNESCO, the first international conference on the linkage between tourism and crafts was held in Tehran in 2006. Its main objectives were to evaluate the opportunities for poverty alleviation through job creation, and the role of tourism in the protection and preservation of traditional crafts, their methods of production and cultural context.

Twenty-first century nomads

- Konstantin Minaychenko

- Bowl from Otrar, Kazakhstan, late 1300s – 1400s, lead-glazed earthenware, 8 x 17 cm. Photo courtesy Oleg Belyalof

Throughout my visits to Central Asia, I’ve been able to see most of its beautiful crafts being made, as well as observe the sad gulf between good and bad quality work. Suzanis for example are arguably the most visible of Central Asia’s urban crafts, and their quality varies greatly from the most exquisite and finely embroidered survivors of the late eighteenth century in its state museums, through machine chain-stitched Soviet examples, to contemporary poor quality mass production aimed at the growing tourist market. While superb quality embroidery does survive in both Uzbekistan and elsewhere, the stalls that line Bukhara’s ancient market and market places throughout the region are today piled high with poorly made, synthetically dyed pieces.

Ceramics comprised the other half of the Bright Flowers exhibition and ensured visits to Uzbek pottery workshops and studios I would otherwise never have seen. We visited Gizduvan near Bukhara, Rishtan in the Ferghana Valley and the serene Tashkent studio of potter Akhbar Rakhimov and his son Alisher. Other traditional urban crafts include exquisite miniature painting, gold embroidery, silk carpet weaving, metalwork, jewellery and wood carving from folding Koran stands to four poster beds.

A highlight of tours to Uzbekistan were visits to the paper-making workshop in Konighil on the outskirts of Samarkand. Established by brothers Zarif and Islom under UNESCO patronage in the 1990s, their workshop is set in a garden with poplar trees and a stream running through. Zarif has a background in ceramics, but wanted to revive Samarkand’s ancient tradition of making beautiful and durable “Samarkand silk” paper by hand. Although Samarkand once had up to 400 paper-making workshops, production ceased in the 1800s until its revival by the brothers. We watched a woman scraping bark off mulberry sticks and putting it to soak, water driving the wooden pestle that pounds the wet mulberry into a paste, the slurry being caught in a tray, then drained and dried on a frame before each sheet was finally polished with horn, stone or shell.

The movement of people, information and materials across the landscape seems to connect cultural tours with nomadism. Considering the almost total eclipse of the traditional nomadic lifestyle in Central Asia, the centrality of nomadic culture to tourism in Kazakhstan and particularly Kyrgyzstan is notable. This is doubtless because of the striking beauty of nomadic material culture and the appeal for us of its perceived exotic freedom and wild open landscapes. Pride in the richness of their material culture and its capacity to declare and characterise their unique nationality at independence has ensured that the principal nomadic arts of carpet weaving, felt making, leather work and embroidery are well represented in the museums of Almaty, Astana and Bishkek. The yurt, which appears in stylised form on the flag of Kyrgyzstan, has become a national symbol that not only reflects their history and a love for their early lifestyle, but has also become a powerful drawcard for travellers. While few yurts now provide portable shelter for pastoralists, there are many which now offer a nomadic “experience” to tourists, thus raising the question of authenticity. In marketing the nomadic experience to tourists, are these host countries capitalising on facsimiles? Perhaps, but does the tourist dollar support the continued valuing and production of traditional crafts in the global economy? Probably.

During my own experience as a tour leader, there have been some memorable encounters with traditional nomadic yurts and crafts, other than museum displays. In 2014 after driving through the desolate but starkly beautiful Kyzyl Kum desert in northern Karakalpakstan, we reached a camp set up with traditional yurts as tourist accommodation on a plateau opposite the ancient Khorezmian fortress site of Ayaz Qala. The view was spectacular, dinner in the dining yurt excellent and, on a freezing night, the sleeping yurts were stove-warmed and the quilts piled high. In suburban Bishkek, we were invited to to see how to make an elechek, the traditional Kyrgyz married woman’s towering cotton headdress. On arrival, we were greeted by four women wearing different elecheks from different regions of Kyrgyzstan who led us into the yurt in the back garden. Women were placed to the right of the door and men to the left, and we watched as the headdress was gradually constructed from scratch on one of my group, beginning with plaiting her hair and stitching hanging ornaments onto the ends. A couple of days earlier, on the northern side of blue Lake Issyk-Kul, we had stopped in Tamchy for lunch in a yurt and met master felt maker Bactigul Assamalieva and her husband, who gave us an excellent demonstration of both types of felt making—shyrdak and ala-kiz (variegated).

Turkmenistan also offered rare cultural and travel experiences. Near ancient Merv, we were very lucky to encounter a group wedding with several brides wearing densely embroidered traditional Turkmen chyrpys (robe) over their heads. Three venues are customary for Turkmen weddings: the bride’s house, the groom’s house and a restaurant; what we saw was when the bride, wearing traditional dress, is taken from her house to the groom’s house where food and drink is served. Sadly for us, the traditional camels had been replaced by highly-decorated limousines. The Turkmen value large weddings, as well as traditional nomadic hospitality, and there are often about 1000 guests.

Turkmenistan today, not least its extraordinary white marble capital Ashgabat, is a far remove from the Turkmen people’s traditional nomadic lifestyle. Fuelled by huge natural gas reserves, Turkmenistan is modernising, after a fashion, but is simultaneously trying to hold onto its essential cultural individuality. Turkmen carpet weaving remains of central importance, although the goalposts have shifted from the personal needs of nomads to production for the local and tourist markets, and to impress. The renowned traditional Tolkuchka bazaar in the desert is no more, replaced by a huge new bazaar with great halls dedicated to different products. We visited the crafts hall and saw where those brides would have bought their machine-embroidered chyrpys, and the concreted carpet area which was a shadow of its former exotic Tolkuchka self. In the excellent National Museum, we saw the biggest Turkmen carpet in the world, which apparently took 38 women over six months to weave; definitely not portable, it was given to Turkmenbashi after five years of his presidency.

Reflecting now on my engagement with Central Asia over the last twenty years, I’m content professionally to know that, in bringing to the Powerhouse Museum an exhibition of rare and lovely objects that may never leave those state museums again, we increased awareness of this significant region as it emerged from Soviet rule. Personally, I am grateful for the opportunity to go adventuring, to delve deeply into different cultures from my own, to travel the golden road to Samarkand at least seven times and fall in love with Bukhara, to have privileged access to precious collections, to see the Kazakh steppes and the mountains of Kyrgyzstan and, through the great endeavour we shared, to make lifelong friends with whom I don’t share a language.

Further reading

Peter Francopan, The Silk Roads: A New History of the World, Bloomsbury Publishing, 2015

Janet Harvey, Traditional Textiles of Central Asia, Thames & Hudson, 1996

Johannes Kalter, The Arts and Crafts of Turkestan, Thames & Hudson, 1984

Johannes Kalter and Margaret Pavaloi, Uzbekistan: Heirs to the Silk Road, Thames & Hudson, 2003

Craig Murray, Murder in Samarkand, Createspace Independent Publishing, 2007

David and Sue Richardson, Qaraqalpaqs of the Aral Delta, Prestel, 2012

Christina Sumner and Heleanor Feltham, Beyond the Silk Road: Arts of Central Asia, Powerhouse Publishing, 1999

Christina Sumner and Guy Petherbridge, Bright Flowers: Textiles and Ceramics of Central Asia, Powerhouse Publishing, 2004

Jon Thompson, Carpets from the Tents, Cottages and Workshops of Asia: an Introduction, Barrie & Jenkins, 1983

Author

Christina Sumner OAM is a textile historian and was formerly principal curator design and society at Sydney’s Powerhouse Museum. Her research interests embrace all traditional textiles, but especially those from Central, South and Southeast Asia. Christina has travelled widely and led tours to Central Asia, India, Bhutan and the Caucasus.

Christina Sumner OAM is a textile historian and was formerly principal curator design and society at Sydney’s Powerhouse Museum. Her research interests embrace all traditional textiles, but especially those from Central, South and Southeast Asia. Christina has travelled widely and led tours to Central Asia, India, Bhutan and the Caucasus.