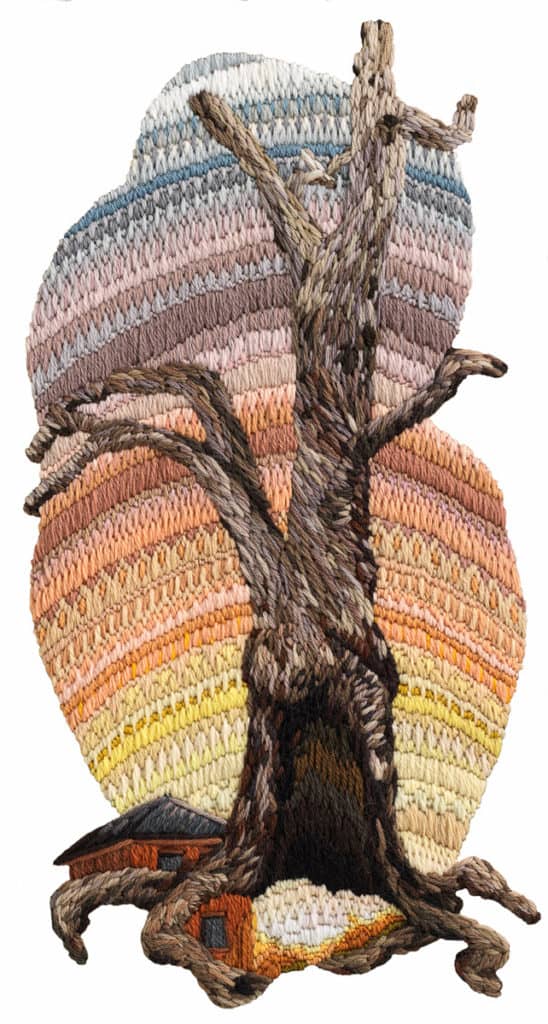

Sera Waters, South Australian cross-sections (in three parts)_ mega-fauna, red stump, finite vastness, 2013, hand-dyed linen, beads, fur, veneer, more, 80 x 80 x 25 cm, photo Sam Roberts

(A message to the reader.)

The idea of layerscapes came to me a decade ago sitting at an Adelaide city bus stop on a cold wintry night.

It was at the same time I was studying the art of Martha Berkeley, who from the late 1830s became South Australia’s first professional female artist. In her watercolours, Berkeley recorded the fledgling colony of Adelaide with its tents, dirt paths, intermittent gums and extensive green grasslands of the Kaurna plains reaching all the way to the hills. Over generations this view has been obliterated by the spread of bitumen, concrete, steel and foundations from which buildings arise, are demolished, and rise again. At that bus stop I imagined that below the city streets, buildings and underground infrastructures are multi-generational remnants from encounters, events, stories, and past endeavours from Berkeley’s colonial-era but reaching way back to time immemorial. The past, in my mind’s eye, sits layer upon layer, generation upon generation, underneath our contemporary surfaces, hidden but teeming with buried knowledge. Reading Ross Gibson’s Seven Versions of an Australian Badland (2002) cemented in me the necessity to rethink places as layerscapes and to investigate and reveal them through my art practice.

Sera Waters Beloved I & II (Her and Him), 2015, linen, hessian, hand-dyed string, lace, doilies, beads, cotton, each 50cm in diameter, photo Grant Hancock

Embracing layerscapes has reinforced my perception of “landscape” as a falsity, a construction which in Australia has predominantly been used to serve colonial agendas. Colonising landscape conventions, as numerous theorists have explored, do not recognise the pulsing knowledge of Country for First Nation people nor the unacknowledged and often brutal events of colonising which have been so systematically disavowed. In this way, layerscapes too, from my own position of inherited ignorance without knowledge of Country, cannot know the intricacies of deeper layers but can acknowledge the affect of the unknown, unknowable and not-to-be-known. I am haunted. Ghosts, and throughout my PhD I used the term ghostscapes, recognising the shame-shaped metaphorical haunting which permeates settler-colonial nations, places and its people. In the case of Australia, I argue the entirety of this land is one spectral aftermath, and Contemporary Australians are inheritors of transgenerational patterns of misuse.

When looking through the lens of layerscapes, this country is also a dump. Settler colonial, especially Victorian era practices of homemaking were based upon the importation, production, collection and consumption of goods; goods which soon became worn, broken, out-of-fashion or no longer useful. At an ever-increasing pace, human-made waste became infill, landfill, and land-piling too. Though we dispose of rubbish (and by extension the past) by culturally and literally throwing it away, burying, disposing, dumping, incinerating, and putting it at a distance, its “material recalcitrance”, to use a Jane Bennett term, haunts us. Often the top layers of layerscapes are material reminders of how settler-colonial homes have been the site of disposal and disavowal, reinforced generation after generation. To unearth these layers I have researched local records, our extensive family history archive, and have examined artefacts of archaeological digs, particularly those dug up by the Flinders University archaeological team from an ancestor’s home from the mid to late 1800s in Port Adelaide. This family’s top layers were mostly objects from homely routines; bottles, crockery, meat bones, décor, and some scraps of textile. In my practice, I experiment with domestic textiles and re-member textile techniques as a conduit to connect back to these homely routines bodily. Beloved I & II (2015) were made with this dig, its findings, my ancestors and their layer in mind.

I have used this research and practice-based approach at other familial sites too. My investigation into a celebrated Riverland rose garden created by my German Grandfather in the 1930s continues to grow in generational layers as I visit the site, talk to family friends and discover other tied in pasts. Fritz and the rose garden (2014) knotted together topographical understandings of this site, with portraiture, research into the Loveday internment camps nearby, family stories, and a teeming tactility. Together they begin to explore the historical, ancestral and cultural remnants which linger in this now decrepit garden, not to mention the ghosts of the First Nations people who cared for this place for countless generations. The layers of this layerscape and this ongoing project look set to match or overtake Gibson’s “seven versions”.

Sera Waters, Falling_ Line by Line, 2018, vinyl wallpaper (adhesive backed and removeable), woollen long-stitches, 2 x 7m, Photo Acorn Photos

Repetitive patterns and rhythmic making are other methods I explore to garner a sense of cultural colonising and felt layers. This links to my evolving theory of repetitive crafting, a form of practice-led research used to dwell and ruminate upon the effects and affect of inter-generational settler-colonial home-making. Blackwork embroidery, pushed to an extreme repetitiveness in artwork South Australian Cross-sections (in Three Parts): Mega-fauna, Red Stump & Finite Vastness (2013), invokes patterns again and again and comes to know them by stitching meticulously over months. More recently my experimentations with long stitched wallpapers, such as Falling: Line by Line (2018) or Hollow Melancholia (2019), have shown me that as I practice I am growing more complex patterns. These patterns grow to reflect the layers of the local and familial sites represented in the wallpapers. Despite patterns often being denigrated as mere decoration, according to Alfred Gell, patterns exude a visual “tackiness” that gets one stuck within the reiterations unable to resolve shifts between lines, back and foregrounds, or tease out exactly how the pattern operates. Experience has taught me that physically stitching a pattern is a way to examine the knowledge patterns hold and come to know them at a bodily level. It is a way of then examining other domestic material and rhythmic modes of colonisation I am also challenging bodily through my knotted and ambiguous ancestral identities of the coloniser, colonised, indoctrinated and activist.

Another part of my endeavour is to unpick how surface practices, particularly clearing and neatening, have been used to damage and conceal layerscapes. Surfaces are exposed, yet layers below can show up through subtle lumps, bumps and markings. I recall Anne Ferran’s photographic series Lost to Worlds (2001) which study the ground’s uneven surface at specifically haunted sites of dark histories. My work Banner of Mine: Cultivation (2017) concentrates on how the surface of South Australia has been restructured to overwrite layers of prior occupation. My banner, constructed of reclaimed and stained towels refashioned into a neat arrangement with fastened fancy edges, hides its layers, messy process and loose threads internally. Like the surveyed land of South Australia segmented into hundreds and mining territories, it is an orderly organisation of blocks arranged line by line. This linear surface is further reinforced with running stitch, which moves geometrically across the whole banner. Embroidery is classified as surface embellishment, and since making this state-shaped banner I have re-thought embroidery as akin to fencing; with both disrupting a surface, suturing in new lines, and leaving behind threads and patterns which change the meaning of regions. South Australia is embroidered with fences which secure themselves into the ground at regular intervals and literally re-order Country with little consideration to previous lines and patterns of the layers beneath. This kind of surface concentration sutures right over the lumps of layers past.

Sera Waters, Banner of Mine – Cultivation, 2017, towels, woollen blanket, trim, glow in the dark thread, metallic thread, brass poles, 320 x 260 cm, photo Grant Hancock

As an artist, invoking layerscapes is a justice driven project, one predicated on truth-telling. It begins the overdue process of taking responsibility for my and my ancestor’s actions and our damage buried within these layers and on the surface. Textile layerscapes importantly reconsider home-craft and domestic textile techniques and recognise home as the place from which inter-generational rubbishing, burying and disavowing have arisen. For me, this research proffers avenues for future textile investigations, using a care-full ethics to give patterns a new trajectory towards recognising the rich buried layers of our locales.

Further Reading

Jane Bennett. “The Force of Things: Steps toward an Ecology of Matter.” Political Theory 32, no. 3 (2004): 347-72.

Bill Gammage. The Biggest Estate on Earth: How Aboriginies Made Australia. Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 2012.

Alfred Gell. Art and Agency: An Anthropological Theory. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1998.

Ross Gibson, “Places Past Disappearance.” In Memoryscopes: Remnants Forensics Aesthetics, edited by Ross Gibson, 13-25. Crawley: UWA Publishing, 2015.

Ross Gibson. Seven Versions of an Australian Badland. St. Lucia, Queensland: University of Queensland Press, 2002.

Susan Lampard. The Respectable of Port Adelaide: Working-Class Attitudes to Respectability through Material Culture. Saarbrucken, Germany: LAP LAMBERT Academic Publishing, 2011.

Sera Waters. “Repetitive Crafting: The Shared Aesthetic of Time in Australian Contemporary Art.” craft + design enquiry (2011).

Author

Sera Waters is an artist based in Adelaide, South Australia. She completed her PhD through Genealogical Ghostscapes in late 2018 with University of South Australia. Currently, she lectures at Adelaide Central School of Art and is represented by Hugo Michell Gallery. Her exhibition Domestic Arts which initially showed at ACE Open, Adelaide, will be touring regional South Australia throughout 2020 and 2021, with accompanying talks and workshops.

Sera Waters is an artist based in Adelaide, South Australia. She completed her PhD through Genealogical Ghostscapes in late 2018 with University of South Australia. Currently, she lectures at Adelaide Central School of Art and is represented by Hugo Michell Gallery. Her exhibition Domestic Arts which initially showed at ACE Open, Adelaide, will be touring regional South Australia throughout 2020 and 2021, with accompanying talks and workshops.