Natasha Sarkar is inspired by the multiplicity of Ramayanas around the world.

In the waning days of October 2011, a storm was brewing in one of India’s top universities. In what felt like an overzealous act of censorship, the powers that be decided to pull A.K. Ramanujan’s thought-provoking essay, Three Hundred Rāmāyaṇas: Five Examples and Three Thoughts on Translation, from the undergraduate syllabus.

At the time, I was some 2000 miles away in Singapore, in the thick of doctoral research in history. Having wandered through parts of Southeast Asia, I had seen firsthand how the Ramayana was not just India’s story—it had travelled, morphed, and taken root in countless ways across borders, languages, and centuries. But back home, things were getting tense. Certain hardline Hindu groups were up in arms over Ramanujan’s essay, claiming its many versions of the epic clashed with their beliefs. For them, the Ramayana was not a fluid, evolving narrative—it was sacred, set in stone, with Ram firmly cast as the ultimate hero. Any deviation from that script felt like a threat. After all, Ram had become more than a myth—he was now a symbol of Hindu identity, and there was a growing push to fix that identity into one singular, unchanging form.

As a practitioner of socially engaged art, I felt compelled to respond.

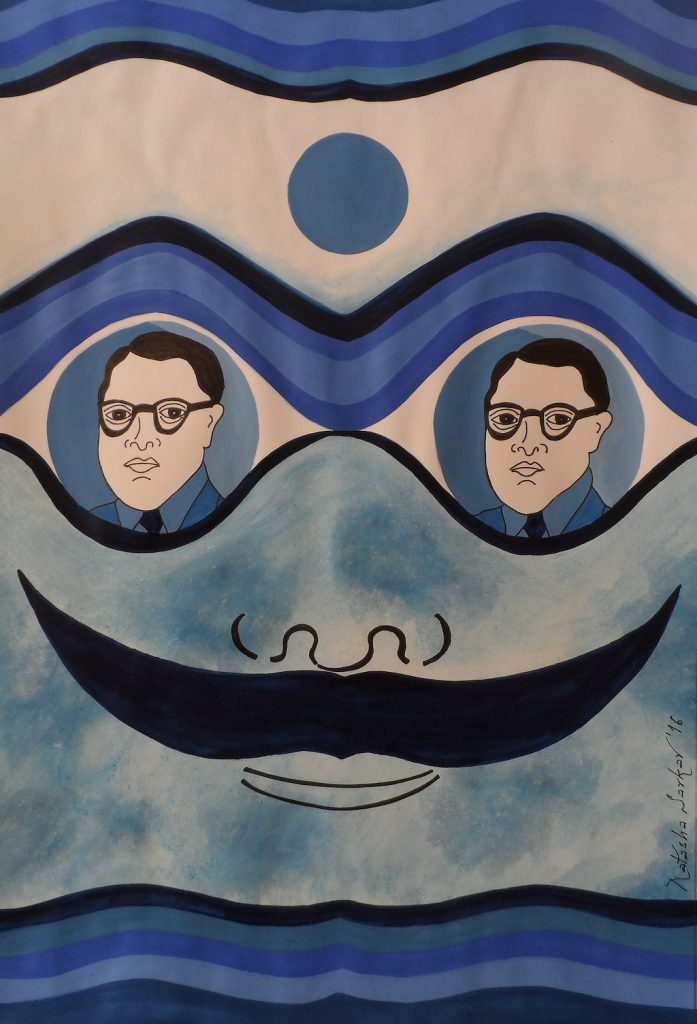

Ramanujan’s essay threw a real wrench into the idea that there is just one true Ramayana. Instead, he laid out how wildly diverse the tellings are, quietly but firmly challenging the idea that Valmiki’s version is the original, untouchable “Ur text.” Naturally, I was hooked. The sheer number of Ramayanas—and how far they had travelled, morphing across cultures in South and Southeast Asia over two and a half millennia—blew my mind. I started digging deeper into these retellings, each one offering a different lens, a different flavour. As a practitioner of socially engaged art, I felt compelled to respond. I wanted to spark conversation, maybe even a little disruption, through a series of close to a hundred paintings that traced the journey of the epic across borders and centuries, demonstrating that the story is not set in stone, but is always evolving.

If we simply make a list of the languages that the Ramayana appears in, it is enough to leave you breathless—it is that expansive. And in some of those languages, the story has been retold, reimagined, and reshaped over centuries. Throw in the plays, dance dramas, shadow puppetry, and other performances, from the classical to the downright earthy folk stuff, and the number of versions skyrockets. The deeper I delved, the more I uncovered across Asia. You could feel the Ramayana’s fluidity in every version that got translated, transplanted, and completely flipped into something new.

Reading anthropological research on the subject was like cracking open a secret door that pulled me into the vibrant world of oral traditions and regional performances. That path eventually led me straight to the heart of Southeast Asia’s masked dances and dramas. My first real encounters were in Thailand and Indonesia where the Ramayana was not just a story: it was woven into the rhythm of daily life. You could see it everywhere: on temple walls, in shadow plays, in the elegance of ballets, all of which reworked the Rama story. Every version I watched or read piqued my curiosity, and before I knew it, I was painting one reinterpretation after another. All those paintings came together in a book I eventually called Whose Ramayana Is It Anyway?—a title intended to challenge notions of ownership and identity surrounding the epic.

As I examined the various retellings, what stood out were the differing perceptions of who or what constituted the ideal hero, and who was considered the true hero. To the Thais, Indonesians, and Cambodians, Ram possessed heroic and romantic qualities but was by no means a God; just a man—flawed, fascinating, and very human. On the other hand, some versions did not shy away from questioning Ram’s actions and ethics. Were they really just? Were his actions always heroic? Not everyone agreed. Ravana, usually cast as the ultimate villain in classical versions of the story, emerged as a misunderstood hero who was noble, learned, and even admirable, while Hanuman came across as perhaps the most powerful character—playful and yet a mighty warrior.

- Natasha Sarkar, “Bali Hatya”, 2015, Watercolour on paper, (15.5” X 10.7”).

- Natasha Sarkar, “Embers Flyin’ in Both Directions”, 2015, Watercolour on paper, (15.5” X 10.7”).

- Natasha Sarkar, “Knockout”, 2016, Watercolour on paper, (15.5” X 10.7”).

I was especially intrigued by how the epic made its way into predominantly Islamic cultures like Malaysia and Indonesia, and even into the Christian Philippines. Instead of rejection, there was assimilation. Through storytelling, dance, and art, the Ram Katha became part of local traditions. The insight gained is best captured in my book when I write, “Through intercultural fusion and dialogue, the Ram Katha became integral to cultures that practised Islam, Christianity, and Buddhism, inadvertently fostering goodwill and understanding.”

Even the story of the heroine Sita was evolving. Far from the usual image of the demure, self-sacrificing wife, in some variants, she was reimagined as bold and independent, a woman who made her own choices. Among the low-caste women of Andhra Pradesh, for example, Sita was not just a symbol of virtue. She was a symbol of freedom, the kind they longed for in real life. Meanwhile, for the Santhals, an Adivasi community, Sita was not the loyal wife but a woman desired by both Ram and his brother Lakshman—an interpretation shaped by their lived experiences, including the cultural acceptance of polygamy in such tribal communities.

- Natasha Sarkar, “Seducing Sita”, 2015, Watercolour on paper, (15.5” X 10.7”).

- Natasha Sarkar, “Unlikely Hero”, 2016, Watercolour on paper, (15.5” X 10.7”)

In India, where caste-based restrictions denied the outcastes from entering temples and worshipping Ram, the worship of Ravana in parts of Uttar Pradesh was a revelation. For such communities, he was not a villain but a symbol of resistance and pride. What is worrying, though, is that in recent times, these alternative tellings—these expressions of diverse belief and lived realities—are being increasingly silenced. The space for multiple Ramayanas, and multiple truths, is shrinking. And that, more than anything, goes against the spirit of the epic itself.

Art has always had this deep, unspoken connection with society. It reflects who we are, but it also nudges us toward who we could be. With this series of paintings, I find myself not just retelling a story: I am inviting viewers to pause, question, and maybe even unlearn a few things. The hope is that these works not only spark curiosity about the Ramayana, but also create space to see it in new ways—through different eyes, from different worlds. After all, there is never just one way to tell a story, and that is where its beauty lies.

About Natasha Sarkar

Born and raised in the vibrant city of Mumbai, Natasha Sarkar brings over two decades of academic and research experience to her evolving journey as a visual artist. With a doctoral degree in History from the National University of Singapore, her deep engagement with teaching and learning has helped her cultivate a worldview sensitive to nuance, open to multiplicity, and drawn to layered meaning. This sensibility finds vivid expression in her art, where pictorial language meets thematic depth. Rooted in historical inquiry and drawn to the rhythms of contemporary life, Sarkar’s work probes the cultural undercurrents of a rapidly changing society—whether in the ever-shifting retellings of mythology, the silent invasions of consumerism, or the politics of ethical food choices. Through bold, conceptually rich imagery, she invites viewers to question inherited narratives and reimagine the familiar. For Sarkar, art becomes a lens to explore, disrupt, and ultimately expand the way we see the world. Visit www.natashasarkar.com

Born and raised in the vibrant city of Mumbai, Natasha Sarkar brings over two decades of academic and research experience to her evolving journey as a visual artist. With a doctoral degree in History from the National University of Singapore, her deep engagement with teaching and learning has helped her cultivate a worldview sensitive to nuance, open to multiplicity, and drawn to layered meaning. This sensibility finds vivid expression in her art, where pictorial language meets thematic depth. Rooted in historical inquiry and drawn to the rhythms of contemporary life, Sarkar’s work probes the cultural undercurrents of a rapidly changing society—whether in the ever-shifting retellings of mythology, the silent invasions of consumerism, or the politics of ethical food choices. Through bold, conceptually rich imagery, she invites viewers to question inherited narratives and reimagine the familiar. For Sarkar, art becomes a lens to explore, disrupt, and ultimately expand the way we see the world. Visit www.natashasarkar.com

Natasha Sarkar, Whose Ramayana Is It Anyway?, Mapin Publishing, 2024.