Yasmin Masri writes about Richilde Flavell’s use of ceramics to explore the transformational experience of becoming a mother.

The first piece Richilde Flavell made after having her oldest child, Caleb, was a terracotta basket. A vessel that fits in the palm of her hand. “It was so small,” Richilde tells me, “really simple and you [could] see all the … pinch marks of my fingers.” The work was made in 10 minutes while sitting on her back verandah one evening.

Although quick, this act of making “felt like such a relief.” As Richilde explains, “I just [wanted] to touch the clay. I just [had] to make something, anything, it [didn’t] matter.”

Ceramics is Richilde’s creative practice. It is how she understands and engages with the world and the way she makes a living. But underneath all of that, at its most fundamental level, ceramics is a kind of emotional regulator. The physicality of the medium—hands on clay—grounds her. As Richilde explains, “Ceramics for me is the thing. It calms me. It’s like [a] meditation … In the moment [of making], and at the moment, I am using [ceramics] more as a therapy.”

The terracotta basket made after Caleb’s birth marked the start of a new body of work for Richilde exploring the transformational experience of becoming a parent. “This little basket was holding my hopes and dreams and desires to get back in the studio.” Made over the last two years, this collection will be presented in an upcoming solo exhibition – Ok! Motherhood at Yarrila Arts and Museum.

When we speak, Richilde is six weeks postpartum with her second child, Luca. She tells me that lately “the only way I can do any work is if he is on me, [if I’m] carrying him.” Her physical contact stabilises, comforts and connects.

Blurring boundaries: fingerprints and stardust

Richilde has been working as a professional ceramicist since graduating from the Australian National University School of Art in 2015. During that time, she has mostly made work on the wheel, producing smooth curving forms, often designed for eating and drinking.

Making work as a new mother required a shift in practice. Objects in progress needed to be able to be left and returned to: to be picked up and put down.

“Unlike most of my previous work, the majority of this exhibition is handbuilt,” Richilde explains. “I have less time in the studio so I really needed to be able to stop and start and hand-building lends itself to that, it’s super practical.”

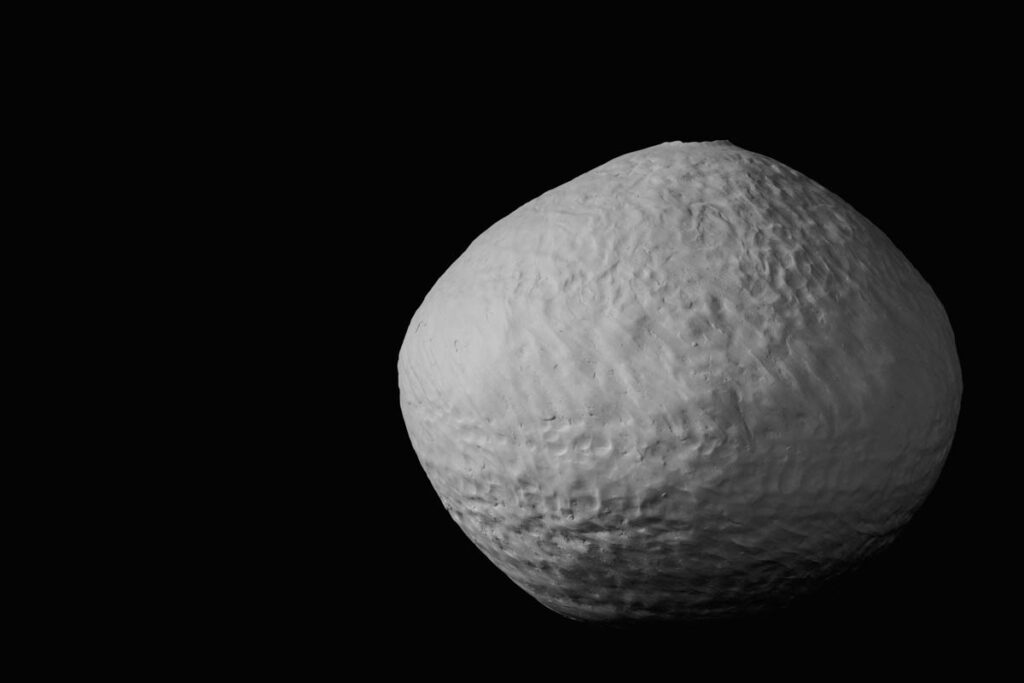

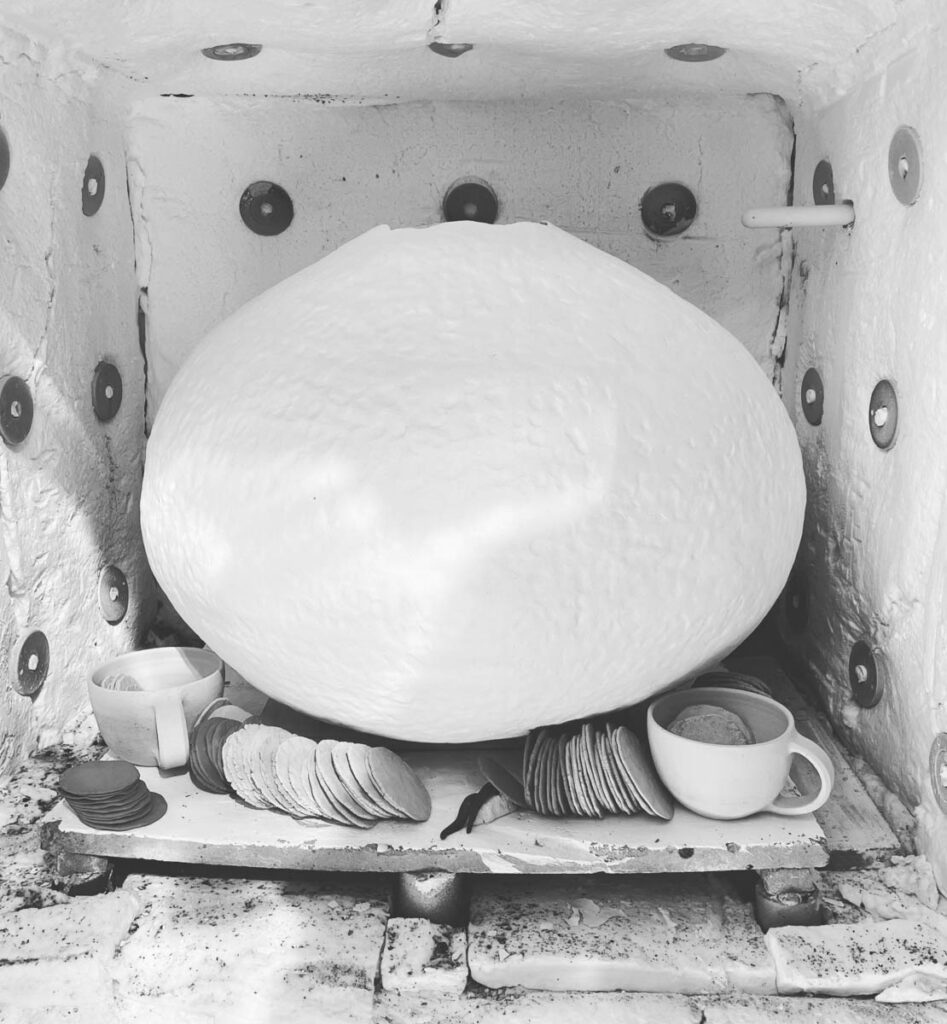

But beyond practicality, Richilde likes the way that this technique records the marks and movements of her hand. This is most clear in her series of large pots. “All of the fingerprints of my life were on the pots,” Richilde tells me. “They are all visible, I haven’t smoothed them away.”

As Richilde reflects, “Having a toddler and being pregnant I really wanted to capture the feeling of having my body being touched so much … the thousands of times little hands have grabbed at my body, have been gentle and rough and playful and all of the things that [you experience] when you’re sharing everything with a small person.”

The large ceramic forms are “an embodiment of the different trimesters and how I was feeling in those times.” They mirror Richilde’s changing body, “I was getting more and more pregnant and … these pots were getting bigger and bigger as well.”

For Richilde, there was a transcendent quality to pregnancy. Although the experience can be “exhausting, filled with hormonal rage, anxiety and never-ending appointments,” pregnancy can also “take you out of yourself and the minutiae of life, it slows you down and makes you take pause.”

Richilde began to think “about work and labour and parenthood and growing a person within the macrocosmic.” That we are all made up of stardust. That we are “[connected] with all of time and space.” And so, the pots are both self-portraits, and representations of celestial bodies. Personal and universal. Small and colossal.

Small touches, small moments, small acts of service cumulate

- Richilde Flavell, Disc, 2023

- Richilde Flavell, Landscape, 2023

Since becoming a mother, Richilde’s time has become more fractured. Divided up into short windows rather than long stretches. Sometimes even working on handbuilt pieces was not possible. “I wanted to capture that moment in my practice where I couldn’t make a whole vessel or anything, [but still] wanted to touch clay,” she reflects.

So, Richilde began making simple, flat clay discs. These were forms that could be made easily and quickly (or slowly). “I take out a pinch of clay and roll it in my hand to [the size of a] walnut,” Richilde explains, “and then I begin pressing and rotating the clay out from the centre.” The results are thin, wafer-like medallions.

Richilde works with whatever clay is around her. Sometimes the clay is coarse, making “edges [that] crack and sort of open up.” Other times, the clay is fine and “[responds] really well to a gentle touch and lots of small pressure … lots of repetition.” Colours shift with the material: off-whites, soft browns, fleshy pinks and oranges.

Some discs, made quickly, can be “quite ragged.” Others have “fine finger marks” or are “quite pinched and pressed.” The making responds to the constraints of the moment. As (right-handed) Richilde explains, “Sometimes I made [discs] just with my left hand because [I was] nursing with my right … those ones are really quite skew-whiff.”

For Richilde, the variation in the discs echoes the experience of motherhood, “sometimes you are doing quite well as a parent and sometimes you’re really not at all.” But the discs are treated with a kind of evenhandedness. All efforts counting and contributing to something bigger.

For Richilde, the discs represent “all of the acts of service that we do for our children … all of the tears wiped, nappies changed, the questions answered, the meals prepared, the cuddles, the stories read.”

“Each disc is like a giving,” Richilde tells me, “in a day, there would be hundreds of these little acts of giving. I see these as [something] that builds up a person … and helps them grow into someone who is a kind, caring, gentle human.”

The discs can be stacked up in towers. They act “like carns when you’re hiking and they lead the way, for safe passage.”

Richilde invited friends to make discs too. She is hoping to create opportunities for audiences to make or move the discs as part of the exhibition program as well. “Hopefully they get some of the … calm that I feel when making the work,” Richilde explains. She wants these interactions to enable parents, and people, to “take a moment for themselves as well.”

Grasp and release, control and surrender

The final series in the exhibition is a collection of vessels. They “are about the ideas that we carry into parenthood,” Richilde tells me. “I’ve made pieces that are for sifting through ideas, carrying ideas, pouring out [ideas].” These are objects for undertaking “the mental work that we do … how we think through and respond to our responsibility as parents.”

In life, we bring tools but sometimes we need to let them go. We find different ways of moving, working, and responding.

In this exhibition, Richilde explores new mediums. Inspired by the wax crayons that Caleb would draw with, she began to experiment with encaustic painting: applying colour with hot, liquid wax.

As Richilde reflected, “[I had to] think about whether I was comfortable making something I wasn’t an expert in.” Unhappy with the initial results, Richilde asked a painter friend for advice. “[She told me] the thing you need to do is slow down,” Richilde remembered. “I’m used to working quite quickly and I know what I am doing and apply glaze in a particular way.” But wax is a different medium.

Slowing down allowed Richilde to engage with making from a different place. “It was actually really beautiful and joyful,” Richilde tells me, “I was able to be gentle and soft and – almost loving and caring with my pots.” The wax needed a different kind of touch.

The allowance of uncertainty in this work has been important for Richilde. “It’s quite scary actually just changing and letting go … but also, [it’s] really great.”

Caleb, now a toddler, wants to be a part of whatever Richilde is working on, “he wants to draw on my art diary, my diary, my everything.” Rather than fight this, Richilde opened up space for collaboration with her son. Once painted, she “[invited] Caleb to come to the studio and scribble all over the pots.”

“There’s this real parallel [between] ceramics and parenthood where you set everything up and you make the routines and you follow the recipes and you do it all … so it’s very organised, but then you also have to … let what happens happen.”

“I feel like my practice has been great training for parenthood, you set it up as best you can and then you let go.”

✿

Richilde’s solo show Ok! Motherhood at Yarrila Arts and Museum (YAM) runs from February 8 – March 24 2024. YAM is a regional gallery on Gumbaynggirr Country along the mid-north coast of New South Wales, Australia.

Richilde’s solo show Ok! Motherhood at Yarrila Arts and Museum (YAM) runs from February 8 – March 24 2024. YAM is a regional gallery on Gumbaynggirr Country along the mid-north coast of New South Wales, Australia.

About Yasmin Masri

Yasmin Masri likes working at the intersection of creativity, community and place. She has started and run festivals, developed and delivered cultural strategy, facilitated community engagement, and produced countless exhibitions, events, pop-ups and creative projects. She also has an independent art practice, which you can see at www.yasminmasri.com.

Yasmin Masri likes working at the intersection of creativity, community and place. She has started and run festivals, developed and delivered cultural strategy, facilitated community engagement, and produced countless exhibitions, events, pop-ups and creative projects. She also has an independent art practice, which you can see at www.yasminmasri.com.