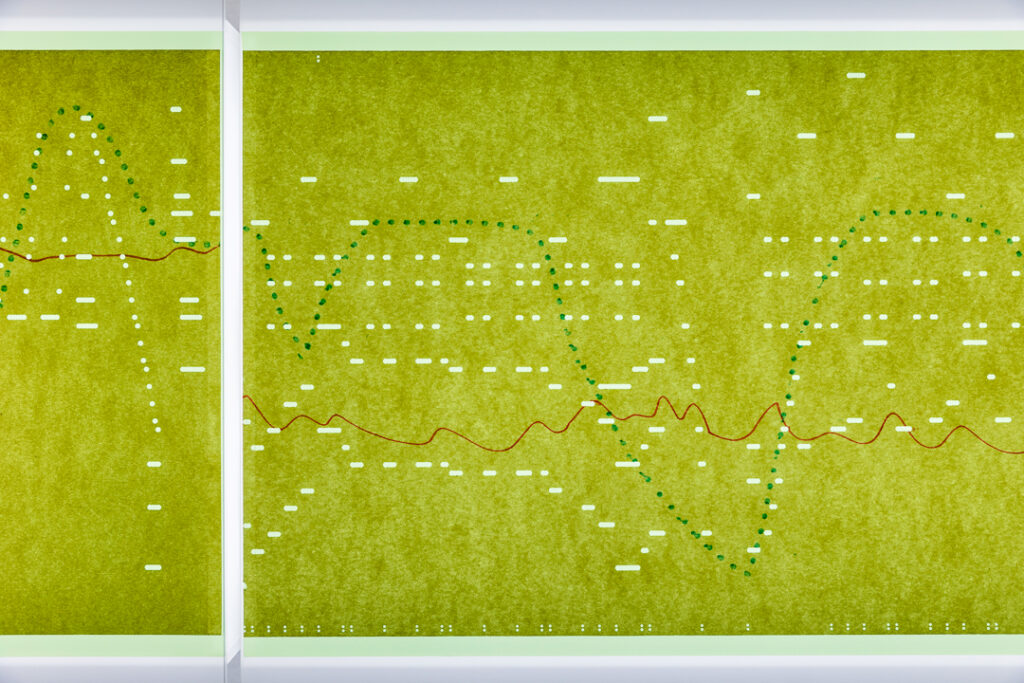

Sonia Leber and David Chesworth, Sound Before Sound I: One and Three Scores (installation view at TarraWarra Museum of Art), 2022. Acrylic, LED lights, paper, stainless steel, 14 channel audio, 50 speakers. Commissioned by TarraWarra Museum of Art. Courtesy the artists. Photo: Andrew Curtis

David Chesworth writes about an artwork using piano rolls to reflect on the materialisation of sound in place and time.

(A message to the reader.)

Sonia Leber and I are curious about the visual appearances of organised sound, how it is captured and stored, and before it becomes manifest. How and in what ways do the symbols and components that give rise to sound (everything that is not the sound itself) appear to us? As potentials, as energies, as data, as an inscription, as an instructional score?

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, piano rolls—continuous paper rolls with holes punched into them—enabled music to be stored and then replayed mechanically on special player pianos. Using these rolls, a human operator performed music without needing traditional keyboard skills. Operating the piano’s foot pedals caused the piano roll to slowly unwind through the player piano’s mechanism. Air forced through the paper’s small perforations caused piano hammers to strike the piano strings musically. Lyrics were sometimes printed on the roll so the operator and others could sing along to the music. Also visible along the length of the rolls were continuous undulating coloured lines that indicated how the music’s fluctuating tempo and dynamic levels could be expressed through tracing the graphic undulations on piano levers.

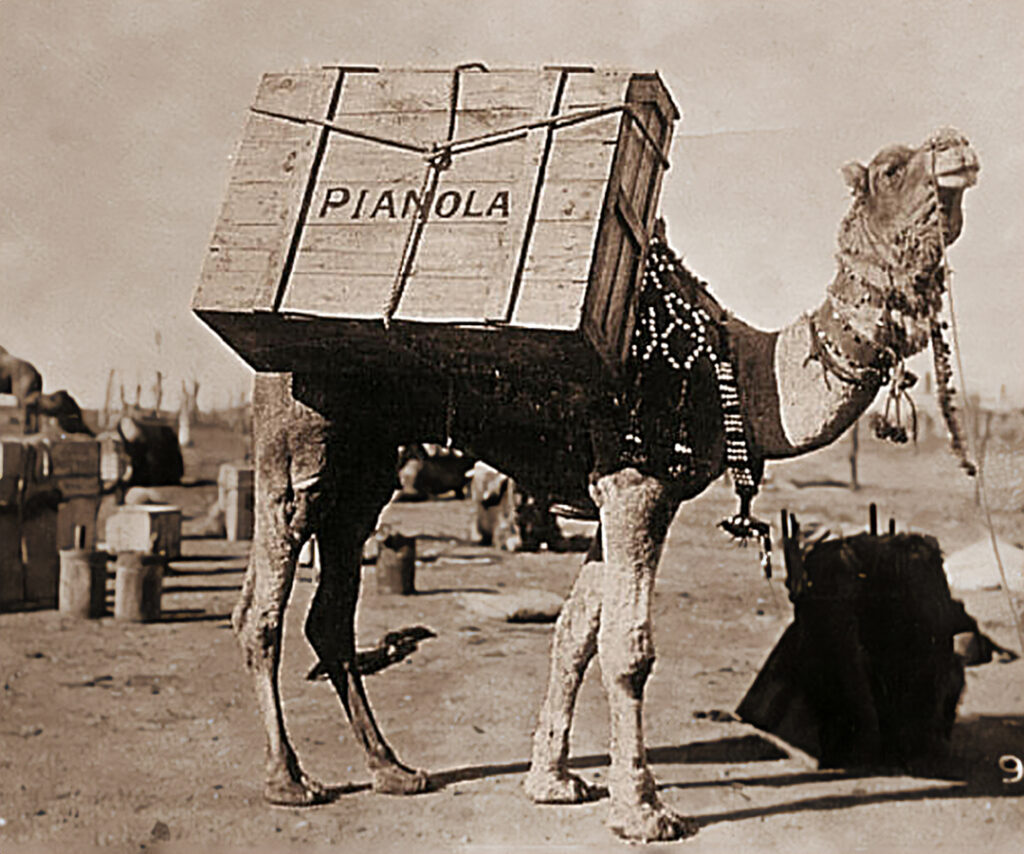

Camel transporting USA Aeolian Company pianola, outback Australia c.1912. photo attributed to ‘a manager of our branch house in Australia’.

Sonia Leber and I were alerted when a collection of old, duplicate piano rolls held by the National Film and Sound Archive in Canberra were offered to the public. Deemed surplus cultural items and being expensive to store, they were split into parcels, and interested parties could bid for each parcel. However, an argument could also be made to receive a parcel for ongoing cultural use. This cultural caveat is how we managed to secure 80 piano rolls for use in our research.

We carefully unfurled the piano rolls horizontally, inspecting their visual appearance. Expressive tempo and dynamic lines, drawn in red, blue and green ink, resembled outlines of natural landscapes. The perforations that control when notes and chords are mechanically played appeared to be more exacting, often arranged in geometric blocks and patterns that were suggestive of human-made forms. These visual referents suggested new expressive possibilities for imaginatively reactivating music’s temporal data as visual and spatial information.

Sonia and I carefully selected two rolls with the idea to combine and align them as illuminated horizontal scrolls. This presentation would allow visitors to explore for themselves the expressive possibilities of the markings and holes: as a visual score, as a graphic data array, as an undulating topography or as an artefact possessing other analogies. The piano roll thus became a score suggesting several readings without it actually being played, transforming the utility of the piano roll so that it might become expressive in ways beyond its original function.

To create the artwork, we developed three horizontal light boxes in collaboration with industrial designers Malte Wagenfeld and Thom Luke. Portions of the rolls were placed in each box over a green gel with acrylic sheets on top. Mounted at eye level and illuminated internally by LEDs, the boxes appeared to float off the walls while emphasising the perforations and inked dynamic lines.

- Sonia Leber and David Chesworth, Sound Before Sound I: One and Three Scores (detail of installation view at TarraWarra Museum of Art), 2022. Acrylic, LED lights, paper, stainless steel, 14 channel audio, 50 speakers. Commissioned by TarraWarra Museum of Art. Courtesy the artists. Photo: Andrew Curtis

- Sonia Leber and David Chesworth, Sound Before Sound I: One and Three Scores (detail of installation view at TarraWarra Museum of Art), 2022. Acrylic, LED lights, paper, stainless steel, 14 channel audio, 50 speakers. Commissioned by TarraWarra Museum of Art. Courtesy the artists. Photo: Andrew Curtis

- Sonia Leber and David Chesworth, Sound Before Sound I: One and Three Scores (detail of installation view at TarraWarra Museum of Art), 2022. Acrylic, LED lights, paper, stainless steel, 14 channel audio, 50 speakers. Commissioned by TarraWarra Museum of Art. Courtesy the artists. Photo: Andrew Curtis

Commissioned by TarraWarra Museum of Art, Sound Before Sound I: One and Three Scores was developed for part of the gallery near a large full-length window overlooking the picturesque Yarra Valley landscape. There is a correspondence between the contours and perforations of the artwork and the cultivated rural landscape framed by the window. This adjacency is conceptually interesting if one considers that both the piano roll and the gallery’s large glass window serve to withhold, contain and curate the viewer’s sensory experience.

It should be remarked that the piano roll is both an inventive storage medium and an artefact of colonial expansion. Pianos—including mechanical player pianos—accompanied many settler colonial penetrations into the Australian landscape, where their familiar European musical cadences would territorialise and domesticise the settler’s surrounding environment.

On the gallery wall, we positioned an array of tiny loudspeakers that unfurl randomly just above our light boxes. The speakers produced delicate sounds, however, instead of recognisable piano sounds, the listener encounters abstract blips, bursts and clicks. These sounds suggest that some other kind of data is present, perhaps a sonification of a sense we can’t fully access or understand.

Sound Before Sound I: One and Three Scores was part of our solo exhibition at TarraWarra Museum of Art in 2022, also featuring our recent video work Where Lakes Once Had Water. This large-scale two-screen work takes viewers on an imaginative journey, exploring the labour of Earth scientists and Traditional Owners as they dig into the arid red soils of Australia’s Northern Territory, reading the signs and signals in the landscape over concepts of deep time. The work contemplates how different, separate investigative pathways and knowledge systems can converge and resonate in surprising ways. We hear Indigenous Elders tell stories and examine the landscape as an archive of information and knowledge. We witness scientists analysing materials and data, creating tables and graphs to translate their landscape readings into visual and spatial information.

Like the scientists’ graphs and tables, piano rolls can also be thought of as repositories of data that reference other sites, situations and experiences.

Like the scientists’ graphs and tables, piano rolls can also be thought of as repositories of data that reference other sites, situations and experiences. Both graphs and piano rolls are abstractions that no longer fully represent the world from which the data was collected. Instead, they await translation, transduction and reinterpretation by acts performed on them. In the piano roll, expressive music, which is temporal, is turned into abstract spatial information from which the original temporal musical performance can be reconstituted. However, the perforations and coloured lines can acquire further expressive possibilities. They become a kind of sound before sound. In a related way, scientists’ graphs also contain data that references the lived world and await an expressive reawakening in the imaginations of a reader who possesses the knowledge to interpret the graphical data.

It is worth reflecting on the human desire to capture and interpret the world that is external to us through our application of different ways of seeing, sensing, listening and thinking. Our anthropocentric ways of knowing the world draw on art, science, philosophy and storytelling. More often than not, this entails withdrawing from our direct sensory relationship with the natural world in favour of its representations.

About Sonia Leber and David Chesworth

Sonia Leber and David Chesworth are known for their distinctive video, sound and architecture-based installations that are audible as much as visible. Leber and Chesworth’s works are speculative and archaeological, often involving communities and elaborated from research in places undergoing social, technological or local geological transformation. Their works emerge from the real but exist significantly in the realm of the imaginary, hinting at unseen forces and non-human perspectives. Leber and Chesworth’s artworks have been shown in the central exhibitions of the 56th Venice Biennale: All The World’s Futures (2015) and the 19th Biennale of Sydney: You Imagine What You Desire (2014). Solo exhibitions include ‘Where Lakes Once Had Water’, TarraWarra Museum of Art, Healesville, Australia (2022) and Drill Hall Gallery, Canberra (2022); ‘What Listening Knows’, Messums Wiltshire, UK (2021) and ‘Architecture Makes Us: Cinematic Visions of Sonia Leber & David Chesworth’, Centre for Contemporary Photography, Melbourne (2018) touring to UNSW Galleries, Sydney (2019) and Griffith University Art Museum, Brisbane (2019). Photo by Madé Spencer-Castle. The artists live and work in Naarm/Melbourne, Australia. Visit www.leberandchesworth.com

Sonia Leber and David Chesworth are known for their distinctive video, sound and architecture-based installations that are audible as much as visible. Leber and Chesworth’s works are speculative and archaeological, often involving communities and elaborated from research in places undergoing social, technological or local geological transformation. Their works emerge from the real but exist significantly in the realm of the imaginary, hinting at unseen forces and non-human perspectives. Leber and Chesworth’s artworks have been shown in the central exhibitions of the 56th Venice Biennale: All The World’s Futures (2015) and the 19th Biennale of Sydney: You Imagine What You Desire (2014). Solo exhibitions include ‘Where Lakes Once Had Water’, TarraWarra Museum of Art, Healesville, Australia (2022) and Drill Hall Gallery, Canberra (2022); ‘What Listening Knows’, Messums Wiltshire, UK (2021) and ‘Architecture Makes Us: Cinematic Visions of Sonia Leber & David Chesworth’, Centre for Contemporary Photography, Melbourne (2018) touring to UNSW Galleries, Sydney (2019) and Griffith University Art Museum, Brisbane (2019). Photo by Madé Spencer-Castle. The artists live and work in Naarm/Melbourne, Australia. Visit www.leberandchesworth.com