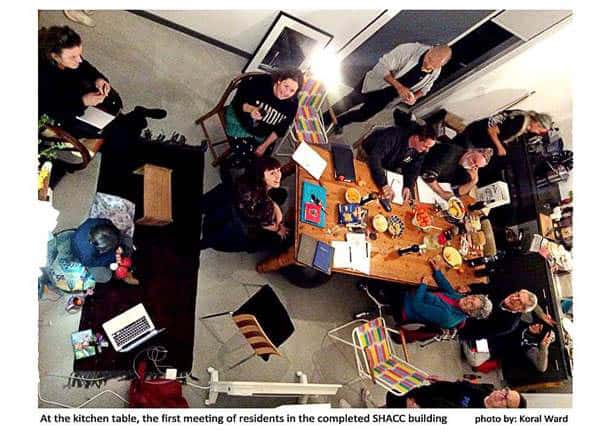

The first meeting of residents in the completed SHACC building takes place inside my “unit”, around my kitchen table—traditionally the site of family and communal meals and stories, of making, planning, and plotting. Here, a community exercises its powers, and perhaps its duty, to create change and as Wendy Sarkissian suggests, to “transform public outcomes”.

The Sustainable Housing for Artists and Creatives Cooperative (SHACC) is a new model of affordable housing. It is purpose-built combined living and working space within a new and primarily residential development, designed particularly for low-income professional artists. Building for an already formed group of individuals has been shown to avoid some of the clashes and ensuing social problems that often arise in dense housing developments where relative strangers are thrown together. It is, in this way, sustaining for the human inhabitants.

We are writing the Rules, forming a cooperative governance model to suit our unique project, which is to secure permanent affordable housing and creative work space for the arts community of Fremantle. In this way we hope to sustain the artistic heritage and creative identity of our port city. Fremantle prides itself on being a city of artists, whose presence in a community is often used as a lure to tourists and provides an incentive to people wanting to move into an “authentic” urban environment. But rising property prices and lack of affordable rental space have had an impact on Fremantle’s art community over the years: many have left the area to find more affordable conditions.

All of us residents and other cooperative members have individual arts practices, or are engaged in creative industries, and also work in the community and public sector, often with the disabled and marginalized. However, the pursuit of a living in creative activities as SHACC resident Lynne Tinley says, “often involves living in a state of quiet or dramatic desperation”. In this SHACC model rents are set to a percentage of income, and it is secured for almost another decade by our Project Agreement with the forward-thinking affordable housing developer, Access Housing.

My space is high and light and has an immediate uplifting effect on entering. It lends itself perfectly to me—for writing and printmaking. There are twelve dwellings of various sizes, and the development is medium to high density, which many Australians find unpalatable, used as they are to large blocks of land with houses squarely placed in them. There are also two communal spaces now being activated—a Community Hub and a Studio Space, dividable for artists to share. We will run workshops in arts practice, cooperative governance and sustainability, and hold events of all kinds. The residents and other members have a wealth of experience in many forms of the arts.

The Cooperative members, with Access representatives, went through a detailed design process with architects Donaldson and Warn. Around the table, the focus was on listening and responding to our needs as low-income professional creative people. D&W wanted to design “a canvas for SHACC life and its art”, and to work with us on growing this new building, in a “needs-driven approach”. The arts are not specifically mentioned in Maslow’s “hierarchy of needs”, though one could argue a place for it at all levels. At the top was giving oneself to accomplishment or understanding of a higher intellectual or spiritual goal; at the slightly “lower” level of needing to reach the potential to be what one can be, and to have esteem and respect for oneself, and at the basic level in the need for “belongingness” and for security of dwellings and space to carry out one’s work.

D&W’s ideal was that “everything should have more than one use”. Units have adaptable internal spaces, and sufficient private outdoor space for work and leisure. Between the two “blocks” of the building are walkways and stairs imagined for use for exhibitions, and performances. This internal courtyard structure allows its use as theatre, promenade, and meeting place, as resident Rachel Riggs says: “holding the present content and action, providing a setting”. We can call it “performative architecture”, it both states and creates its uses and intentions.

The port city’s sea container aesthetic is reflected in the outer façade of SHACC, and the inner ‘courtyard’ has the feel of the gangways and decks of a ship. The built form can be an expression of historical and cultural influences, and also reflective of shifting values. The very “skin” and exo-skeleton are instantiations of our intentions and hopes. Dana Bixby writes that the “skin” or façade is “considered to have a social and cultural role in representing what is inside the building”. It can also be understood as forming a “tangible” connection, “integral to the space” between its inside and outside parts. In this instance it represents movement between creative people, intersections of our lives and endeavours and spaces of interstices with each other where dynamic collisions and collaborations occur.

It doesn’t end at the boundaries of the building however, we understand ourselves as part of a wider development, instigating and nurturing creativity. The common myth that people believe about themselves and the arts, is that it is the province of other people, “I’m not creative”. Yet creativity is necessary to solving the most everyday problems, and it’s the same skills that are used to create imaginative objects of beauty, or meaningful poems, dazzling wall art and performance: things that enhance human life. It is the skills that can address the problems we face of sustainability of resources and beings. According to Christiaan Grootaert: “Sustainability is to leave future generations as many, or more, opportunities as we ourselves have had’’.

This project began a decade ago in White Gum Valley, around another local kitchen table in a dilapidated cottage that had been in artists’ circles for 20 years. We still have some original members from the early days, which is significant when considering that such long-term initiatives run on the enthusiasm of individuals. We come together with shared values, intentions and dreams of creating change.

“Dwelling” suggests continuity of habitation, a deep belonging to place, and caring for it to make it sustainable. The SHAC Cooperative sits on the edge of a Landcorp initiative in sustainable living in White Gum Valley, WA which is only the 11th project worldwide to be given One Planet Living accreditation and we strive to fulfil its ten principles. As Seamon and Mugerauer say: “A new attitude and approach are called for and underway, as thinkers, builders, scientists and poets struggle to find a new way to face our situation”. Perhaps all new housing developments should have creative hubs and resident artists. We are still wondering at our good fortune, most of us have never lived in a brand new space before, we are “at home”, and working in our milieu.

Further reading

Bixby, Dana, Building Skin as a Connector – Not a Representation , Proceedings of the 7th International Space Syntax Symposium, Edited by Daniel Koch, Lars Marcus and Jesper Steen, Stockholm: KTH, 2009.

Christiaan Grootaert, Social Capital Initiative, Working Paper No. 3. SOCIAL CAPITAL: THE MISSING LINK, The World Bank Social Development Family Environmentally and Socially Sustainable Development Network, April 1998

Sarkissian Wendy, et al, Kitchen Table Sustainability: Practical Recipes for Community Engagement with Sustainability, Earthscan, Routledge, 2008

Seamon and Robert Mugerauer (eds), dwelling, place and environment: towards a phenomenology of person and world, David 1985, Nijhoff Publishers, Dordrecht.

Author

Dr. Koral Ward is a writer and printmaker. She has been a theatrical costumier and performance poet, and is knowledgeable about one vast yet infinitesimal thing about which she published ‘Augenblick: The Concept of the Decisive Moment in 19th and 20th Century Western Philosophy’ in 2008. In the present moment, she is writing a sequel which connects the Western philosophical rendering of the Moment to the Eastern, most notably found in Zen Buddhism. She lives in Fremantle WA and is vice-chair of Sustainable Housing for Artists and Creatives Cooperative Inc.

Dr. Koral Ward is a writer and printmaker. She has been a theatrical costumier and performance poet, and is knowledgeable about one vast yet infinitesimal thing about which she published ‘Augenblick: The Concept of the Decisive Moment in 19th and 20th Century Western Philosophy’ in 2008. In the present moment, she is writing a sequel which connects the Western philosophical rendering of the Moment to the Eastern, most notably found in Zen Buddhism. She lives in Fremantle WA and is vice-chair of Sustainable Housing for Artists and Creatives Cooperative Inc.

For more information visit us at Facebook or www.shacfreo.com

Comments

Wow.. What a gal.. Congratulations on your achievements dear Koral