Jack Wilkie-Jans writes about two artists from Cape York Peninsula whose connection to Country includes Men’s Shed and cultural maintenance.

Sacred Men’s Business are practices in Lore and ceremony—and kinship responsibilities—which were [perhaps] most hit at the first instances of colonisation. Our men—warriors—were the frontline of deliberate colonial military and filthy militia efforts to eradicate and move “back” our peoples from the land desired for frontier development. Of course, our women would be preyed on mercilessly and ambushed. Later, our children were kidnapped, abused and indoctrinated. For generations, our men and women were forced into conditions tantamount to slavery and debasement. And, today, our blak young men are some of the most surveilled and targeted by colonial forces. Yet—as a people—we overcame, survived and continued to remember Old Ways. In the visual arts today, our men are standing strong, upholding and telling our stories. Uncle Syd Bruce Shortjoe and Bernard Lee Singleton, from Tropical North Queensland, are two of the finest examples.

It’s true, there remains a visible imbalance between men and women artists engaging both in remote Indigenous art centres and with works available readily on the primary and secondary markets. Women artists are as exalted as they deserve to be in their impressive numbers, though they can always be better supported and protected from crooks. They are our great matriarchs. But, male artists are still the minority. However, they are not necessarily the minority in communities and on homelands, within families, and certainly not in terms of possessing great Cultural Property and Spiritual Authority. In several important art forms and schools, our male artists have been at the helm of revolutionary innovation. However, many of these (often younger) male luminaries have what can only be described as the “university rinse”. This isn’t a disparaging statement. This has, in effect, been pivotal in seeing our contemporary arts taken overseas and held to critical and commercial standards with the rest and best of them! Likewise, our women artists deserve equal credit in this important global space of recognition.

Uncle Syd Bruce Shortjoe of Pormpuraaw (Western Cape, Cape York Peninsula) and Bernard Singleton of Gimuy/Cairns (Tropical North Queensland) are two male artists—one senior and one relatively junior—from different corners of the North. Uncle Syd is from where the sun sets, and Bernard’s from where it rises. Together, these two gentlemen artists are vital Lorekeepers, practitioners and storytellers. Both, while incredible and diversely talented artists, play important roles in the preservation and education of significant Cultural practices, and in other ways supporting their people and families.

I first met Bernard in 2014, through a group show at Umi Arts (Gimuy/Cairns) in which I, Bernard and his partner, Simone Arnol, were featured artists (along with many others). In more recent years, I’ve been fortunate enough to purchase a sister-pair of a spear + woomera owned by QAGOMA. These exquisite pieces are made from Normanbya normanbyi/Queensland Black Palm. Bernard and Simone, I consider to be dear friends. Whereas, Uncle Syd was known to me for a lot longer. He’s a familiar and friendly face around the Cairns Indigenous Art Fair. It was from 2016 to 2018 when I worked for the historic Australia: Defending the Oceans project, which saw a vast collection of contemporary Indigenous sculptures (including ghostnets) travel to eleven venues across Europe and North America. This project featured many Pormpuraaw artists, including Uncle Syd, Erub and Badu Island artists, as well as ones from Girringun/Cardwell and Ceduna. On parts of this tour, I would travel with Uncle Syd to Monaco, Paris and New York City as part of the project ensemble. Of course, for Defending the Oceans, sea conservation was the artistic message writ large. Ghostnets, as a medium, speak to poor maritime and fisheries practices, which threaten native and migrational aquatic, totemic species.

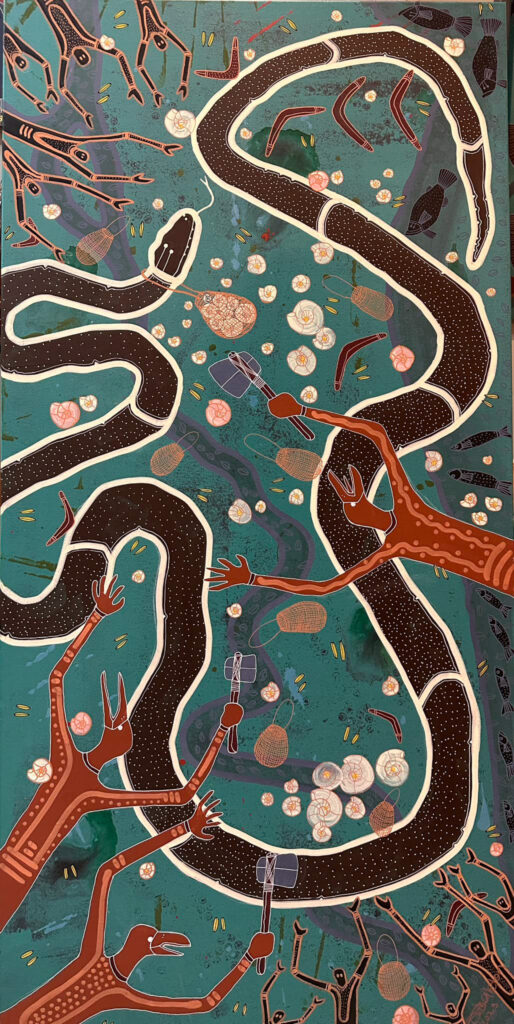

- Bernard Singleton

- Bernard Singleton

- Bernard Singleton

Both these beautiful and impressive swathes of Country, belonging to each artist, suffer from a myriad of threats to their sustainability: climate change, or specifically rising sea levels, and drier wet seasons leading to more unmitigated bushfires. These landscapes on both the western and eastern sides of the peninsula (the “pointy bit” of Australia) aren’t unknown to land clearing and cattle grazing and an influx of feral pests (both animal and weed variety). There is also mining, both small and large scale, historic, current and proposed (as these regions boast immense rare earth mineral deposits). While both Uncle Syd and Bernard don’t directly reference these themes overtly in their art, they are keenly aware of them. They feel that telling the stories that make their respective Cultures strong and timeless is one direct way to teach and warn of what’s at stake.

Pormpuraaw is one of the most beautiful places on the Western Cape of the peninsula. Its Country is home to the Thaayore, Wik, Bakanh, and Yir Yoront peoples. With a close-knit population of around six-hundred residents, the community is steeped in thriving cultural practice as well as arts. Uncle Syd is a senior Wik-Iiyanh man and artist in Pormpuraaw. His works on paper, canvas and with ghostnet weaving are celebrations of the forests, colourful swamp lands, river ways, and beaches (which reflect the greatest of sunsets). Certain works (most of his works are largely figurative), mainly those on paper, tell the stories of the town and its people, histories and totemic species for hunting and fishing. His paintings, mostly entrancing and far-seeing landscapes, depict Uncle Syd’s Country, which are places to remember ritual and go hunting.

Bernard is an Umpila, Djabuguy and Yirrkandji man. His homelands are where he still lives and works today—though, he also has ties to Yarrabah just south of Gimuy/Cairns and works a lot supporting the artists of Yarrabah Art Centre (alongside his partner and also artist Simone, a Gunngandji woman, who is the art centre manager). His Djabuguy and Yirrkandji Country covers part of Cairns City and north (encompassing some of the world’s best beaches), as well as the emerald rainforest Country of Kuranda area and beginning of the Great Dividing Range. His Umpila Country covers part of Central Cape York Peninsula, east of Archer River and Coen.

Both men work with their hands. Bernard is most known for his artefacts and for his exemplary skill in carving, but also for said artefacts’ practical applications (which is not encouraged to buyers). Knowing the Lore behind his peoples’ artefacts, their correct making and his firm adeptness at their practical uses, sets Bernard’s works in a very rare space compared to other practising artists today. Of course, he is a painter as well, much like his father, Dr Bernard Singleton Snr (a ranger, archeologist and public health expert). Uncle Syd works with his hands also: he is a master with wood and weaver of ghostnets.

These days what keeps him busiest outside of the art centre is his work with the Men’s Shed. The Men’s Shed in Pormpuraaw is a place where, as Bernard learned from his father and Old People, the youth of today can learn from the likes of Uncle Syd and other senior men, in a workshop and under Cultural guidance. Men’s Sheds is a concept that runs across many Aboriginal communities, whereby young and senior men can learn practical skills and transference of knowledge in a manual arts space. They engage in communal well-being through the making of wooden keepsakes and sometimes work on infrastructure builds and repairs for various community-led enterprises. Together, they learn and teach carpentry. The Pormpuraaw Men’s Shed, situated on its own recognised plot, was built by the Australian Defence Force in 2021 and has become a valued programme and meeting place for the menfolk of Pormpuraaw.

Further to this, both artists demonstrate leadership in other ways to young men: Uncle Syd is a long-time director to the Board of the Pormpuraaw Art & Culture Centre, and Bernard works with the Cape York AFL House which transitions male high-school students into sports and academic pathways.

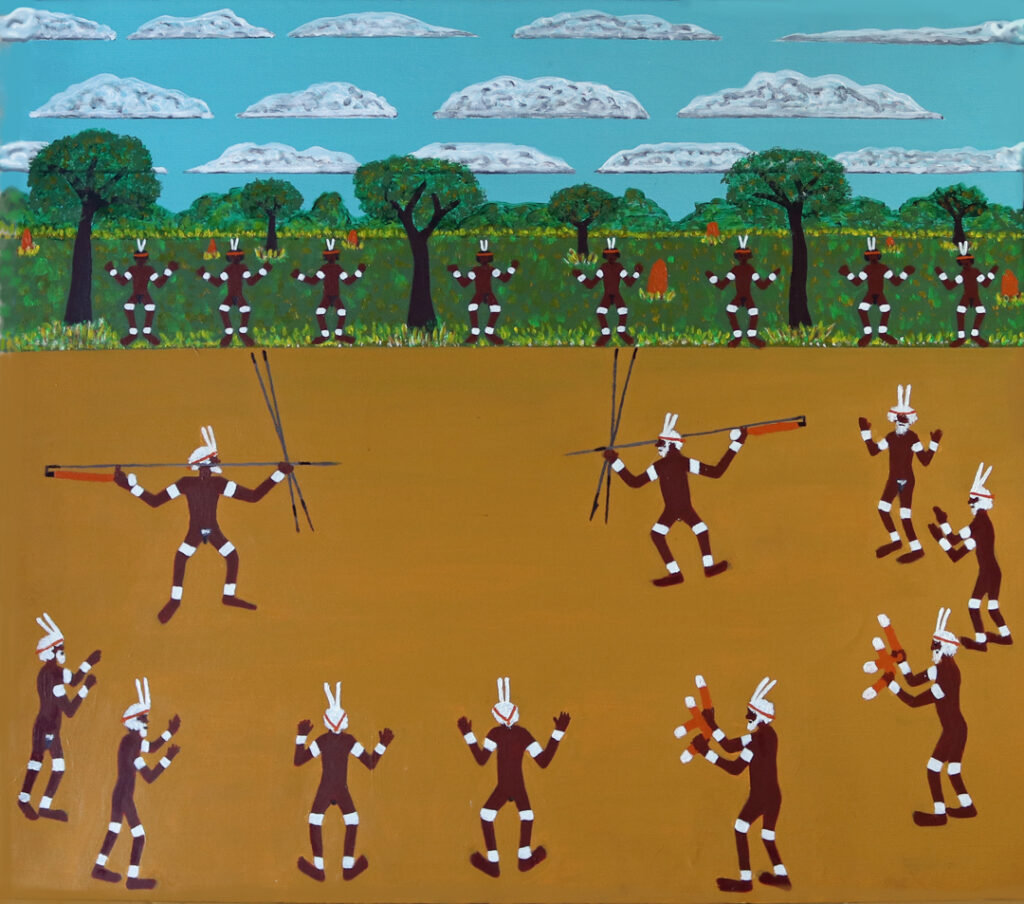

- Syd Bruce Shortjoe

- Syd Bruce Shortjoe

- Syd Bruce Shortjoe

Both men are painters. Uncle Syd’s works on canvas, as aforementioned, are mostly figurative and landscape. They often depict scenes of ceremony and on-Country practices. Uncle Syd’s works are quintessentially “Pormpuraaw” and you can see the textual quality of his brushwork, giving an alive quality to them, like the breeze gusting through the shrubs and bracken. Uncle Syd’s works should be most celebrated for their aptly colourful depiction of the landscapes, in particular the skies above them, emphasised by their almost aerial perspective. He enjoys working on medium to large-scale size varieties. They are “works of scale” also in that they say much and are accurate visual records.

Both men are painters. Uncle Syd’s works on canvas, as aforementioned, are mostly figurative and landscape. They often depict scenes of ceremony and on-Country practices. Uncle Syd’s works are quintessentially “Pormpuraaw” and you can see the textual quality of his brushwork, giving an alive quality to them, like the breeze gusting through the shrubs and bracken. Uncle Syd’s works should be most celebrated for their aptly colourful depiction of the landscapes, in particular the skies above them, emphasised by their almost aerial perspective. He enjoys working on medium to large-scale size varieties. They are “works of scale” also in that they say much and are accurate visual records.

The same can be said of Bernard’s works on canvas, though, he is across photography, a pencil, sculpture, and textiles, too. There’s something altogether positively different about Bernard’s works. They call you in, due to how close-up subjects are framed, as opposed to Uncle Syd’s which watch sacred business from afar, appropriately not giving too much away in their stillness. Bernard’s have a smooth application from ample paint and a colour scheme that is buttercream soft, playing with depth in contrast fashion. What works Bernard is producing these days are mainly scenes from the world of water. They depict an entrancing tableaux of aquatic life that thrives between submerged mangrove forest roots, which are remarked to be of the utmost importance to ocean health and biodiversity. They are glimpses into the unknowable for us humans, periscopes into a magic world. His works also have something of the spiritual to them. Bernard’s pieces often feature Hairy Man, spirit guides, or watchers.

Where Uncle Syd’s paintings showcase what we can see, Bernard’s depict what we necessarily cannot. The artworks by both are certainly worth seeing and collecting (if you’re lucky enough). Both men know Country and Lore and possess great love. Make no mistake about it, when working or talking with them: You’re with propa men. They’re standing in the spotlight, showing how important the knowledge of these important men is to our Cultures and to our arts.

About Jack Wilkie-Jans

Jack Wilkie-Jans (Jack Jans) is a leading First Nations arts worker, writer and policy theorist. With a stellar background in presenting contemporary Indigenous art events and exhibitions across Australia and abroad, Jack is an emerging artist himself as well as an artist agent. He is a proud Waanyi, Teppathiggi and Tjungundji man, also of British, Vanuatuan and Danish heritage. Currently, Jack is based in tropical Gimuy/Cairns, Queensland.

Jack Wilkie-Jans (Jack Jans) is a leading First Nations arts worker, writer and policy theorist. With a stellar background in presenting contemporary Indigenous art events and exhibitions across Australia and abroad, Jack is an emerging artist himself as well as an artist agent. He is a proud Waanyi, Teppathiggi and Tjungundji man, also of British, Vanuatuan and Danish heritage. Currently, Jack is based in tropical Gimuy/Cairns, Queensland.

Comments

Wonderful work Jack 🙂