Salome Katamadze records her residency at the Domaine de Boisbuchet working with landscape to bridge sky and land.

I had been living in Milan for a year and a half when I applied for the artistic residency at the Domaine de Boisbuchet near Lessac, France. The reason for moving there was the start of my PhD at Politecnico di Milano at the Faculty of Architecture and Urban Studies. Due to my background, passions and activities, which I have been carrying since I left my home country, I somehow managed to gather all the dots of my interests into one massive cloud of curiosities, connecting Landscape Architecture with conflictual borderlands, land-based practices and the Caucasus mountains.

Through my enthusiasm and intuition, I have been searching for ways of looking at the frictional borderline from the perspective of the landscape, its qualitative representation and alternative perception of ongoing conflicts and their spatial implications on the communities inhabiting the frontier line between Georgia and the Russian Federation. Sometimes, it might be deceptive to think, narrate, write and open up discussions in an office room on the University campus, while the topics you are relating to are intertwined relationships between people, land, nature, history and morphology of the places in the remote, infinitely high, and often unreachable mountain territories. When I saw the open call for doing a month-long research project in an isolated, completely contrasting geographical context from what I have been working on, I decided that this might have been the right occasion to experiment with specific methodological approaches to landscape mapping, perception and observation of it, advanced in my studies, however in the theoretical dimension of it.

I sincerely believe in understanding the landscape as a cultural and visual artefact, which can offer unlimited perspectives of dynamic processes that usually co-exist without leaving conspicuous traces. I always search for the alternative narrative of the landscape where the neglected or invisible phenomenons overpower the picturesque perception of it. That was also the starting point for the experience in the region of Charente, where I was heading, to create observation and representation tools for the places of ambiguities where entanglements and contradictory exchanges occur.

Even though I had a precise idea of the working themes, I could not predict the very elements of the landscape I would work with, the contradictions I would find on the long walks in the fields or the peculiarities that could tackle the idea of invisible, ephemeral sides of the place. I was open to the things to happen while hoping to be at the right place at the right time.

The residency premises were around an hour’s drive from the nearest city where I managed to arrive. After crossing the southern countryside, I found myself completely isolated, however, in a place with a particular richness and generosity in the variety of inner and outside spaces to offer. It felt like being in a tiny collection of microcosms, where the territory’s characteristics, the light, pigments of green, could transform within several minutes, and the unpredictable changeability of the weather, typical to the mountain areas, further enhanced the constant mutation of the surroundings.

It took me several days to get used to the feeling of detachment from certain daily life dynamics while another type of routine started to open up. It became difficult to distinguish which part was remote, the countryside where I was bumping into a group of fawns and hares on the usual afternoon walks or the anthropocentric reality that became a regularity.

The possibility of complete immersion into the landscape incentivises profound observations and understanding of the place. Therefore, I started to explore, walk, listen, and smell. Within the process of absorbing surroundings, I was also trying to grasp the scientific dimensions of the ecosystem. Thus, after long hours spent outside, I would flee into my minuscule room, with an enormous window directly framing Alvaro Size’s pavilion and a small detail from the nineteenth-century Japanese house dissembled and assembled next to the miniature forest of bamboo, to draw, write, and search for what I had been looking at during the first part of my inquiry.

Soon, I noticed that wherever I went, there were two constancies: first, the sound of birds, as if the silence was a forever precluded aspect of the landscape, and second, the water. Even if I were distant from the lakes and river, I could hear the water underneath; the delicate scrolling sound, like the infinitesimal cascade, was permanent under my feet. I trampled the land, I stepped on the grass, and all I could hear was the water. This enormous energy, in continuous movement, was the land itself. Neither were the nights silent. When it would go dark, a completely different bird spice orchestra would start.

The darkness was absolute. The nocturnal landscape was as powerful and alive as the daily one, surprisingly still not eradicated by the invasive light pollution majorly typical to the urban areas. Hence, I started wondering where the limit to the sky was. Why do we mainly refer to the soil in our conception of the territory? Why does the understanding of the landscape stop at the horizontal line? The land is at the lower limit of the sky. Within several days of my exploration, I started to concentrate on envisioning and observing the land through the characteristics and phenomena of the sky.

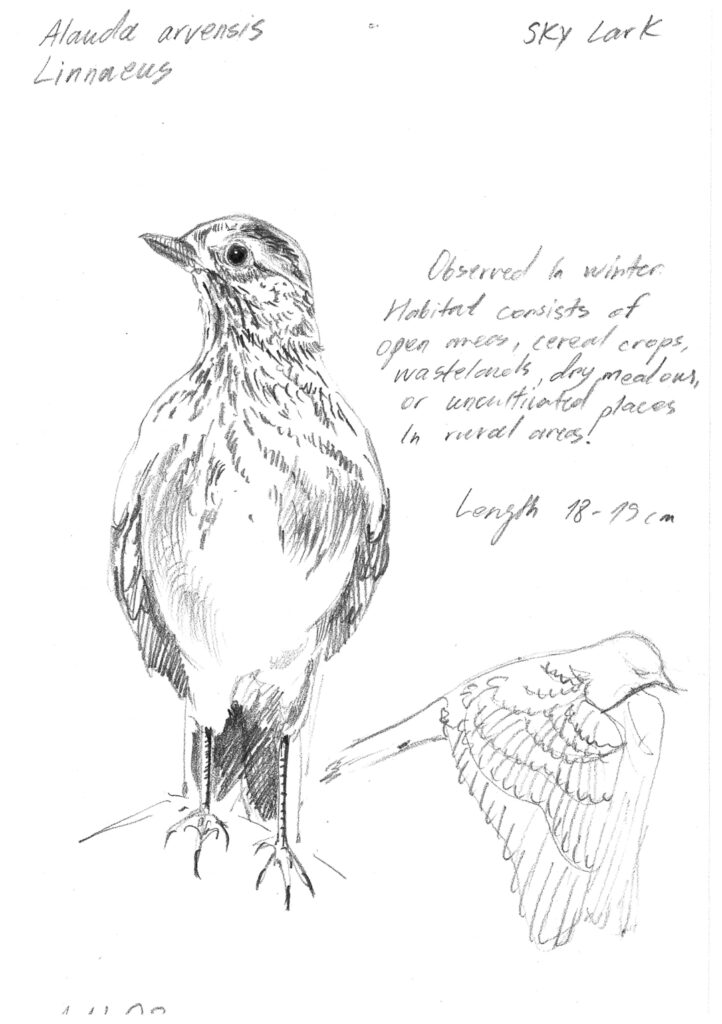

After several dives into research, an invisible, however extremely attendant, entwined system of bird migration and movement routes floated up. From long-distance mobility, originating from the far north and heading to Africa, to the abundance of the sedentary presences, an utterly alternative perspective on the territory was generated. Even though their movements at first glance seem detached from the land, the multi-scalar displacement that regionally and internationally took place was strictly connected to the season, climate, and temperature change, which rendered the birds intrinsic actors and narrators of the local landscape. Through the project “Upside-Down”, I started to reflect on the temporary evidence of migrations, flows, and mobile networks deeply characterised by the land. Because of the ability to navigate and the orientation of feathered creatures, the movement is never random but always composed of a performative act, where the landscape becomes the stage.

The skies were drawn by endless trajectories and patterns all year round. Migratory birds traversed along invisible paths through these lands. More sedentary birds intertwined their lives with these seasonal travellers. I looked at them as tiny presences that revealed themselves only to the most attentive and dedicated ones.

For me, the Upside-Down landscape, where the land became the limit to the sky, required different tools and artefacts of exploration. I started to draw maps of the movements, sketch the identified bird species, and create a photographic archive of the birds belonging to the place where I was just a passing stranger. I wanted to work outside, be part of the territory, adapt to its mutations, and follow the transformations while observing these infinite networks threading above my head.

As an architect, I started working on a prototype that I could use as an artefact for landscape exploration, connecting the land with the sky and englobing the ambiguities and complexities of the animal-human exchange relationship. I started to explore a lightweight octagonal steel structure, which would roll from one field to another in search of birds, their lives, their stops, and their passages. A structure that combined stairs for humans and a platform for birds, where the object’s geometry facilitated displacement despite its weight, height and scale.

After two intense weeks of pioneer-level welding, where I felt like a medieval fairytale dragon spitting the fire capable of razing everything to the ground, the prototype named Daedalus was made, and the first question that came to my mind was caused by the vagueness towards its users, purposes and destinations. So, who was it for? For humans or non-humans, or both? The ephemerality of the structure permitted the artefact in specific scenarios to disappear and be entirely dominated by the surroundings. Daedalus became architecture in monition, only temporarily resting on the ground, with the same texture as the threads in which birds rest. It became a place to observe and be observed by humans and nonhumans alike.

About Salome Katamadze

Salome Katamadze is a Georgian-born landscape architect and researcher based in Milan, Italy. She has been researching landscape, borders, frictional territories, and their representation throughout a long-term investigation, starting with her MA thesis, followed by a fellowship at Fondazione Benetton, leading to her current PhD project at Politecnico di Milano. Since 2020, she has been a co-founder of an architecture office, NOIA practice, operating both in Italy and Georgia.

Salome Katamadze is a Georgian-born landscape architect and researcher based in Milan, Italy. She has been researching landscape, borders, frictional territories, and their representation throughout a long-term investigation, starting with her MA thesis, followed by a fellowship at Fondazione Benetton, leading to her current PhD project at Politecnico di Milano. Since 2020, she has been a co-founder of an architecture office, NOIA practice, operating both in Italy and Georgia.