Last summer, I had the opportunity to join a private tour to the Jianfu Palace Garden or the Garden of the Palace of Established Happiness in the Forbidden City, former imperial palace complex that now houses the Palace Museum in Beijing, China. The Garden was the first commissioned by the Qianlong emperor (r.1736-95) and presumably his favourite was based on the significant art and antiquities collection it used to house. It was destroyed entirely by a mysterious fire in 1923 during the time of Puyi, the last emperor.

In the 1990s, China Heritage Fund (CHF) initiated and fully funded a massive reconstruction effort of the Garden in partnership with the Palace Museum—the first construction in the museum since the imperial period. The Garden was restored to its former glory in 2005. Since handover to the museum’s management, it has been used predominantly for diplomatic receptions. Although officially part of the World Heritage Site (Forbidden City), access to the Garden is by invitation only and has limited exposure in the media and to the public.

The Garden once stored the private art collection of a great emperor, including the Admonitions scroll, a work of ink and colour on silk, now with an original but incomplete version in the British Museum and a copy from the Southern Song Dynasty in the Palace Museum. Today it serves as a tangible symbol of national memory and identity. As I walked through the exquisitely adorned ancient Chinese architecture, I have to admit that the Garden provided a particularly intimate moment for me, a Chinese, to connect with the legendary cultural past. I got to talk in length with Harun from CHF, who managed the project, about this special voyage of restoring the Garden.

With a mission of nation building and a sense of collective ownership of the now “national cultural heritage”, the CHF was founded and embarked on a journey to reimagine the grand era of the Jianfu Palace Garden. The restoration was an outcome of collaborative efforts discovering old and navigating new social fabrics of craft communities. In the process, it also revealed that the preservation of intangible heritage craft is closely connected to the feasibility of an authentic process in monument conversations.

Who was the architect?

Unlike a western garden, a Chinese garden is more about architecture than horticulture. The Pavilion of Tranquil Ease and the multi-storied, five-bay square edifice Pavilion of Prolonged Spring are most significant. The rest of the garden is packed with gates, shrines, studios, a rockery and more. It was a display of intricate architectural variety—a place created for inspiration and for exhibiting the emperor’s personal taste.

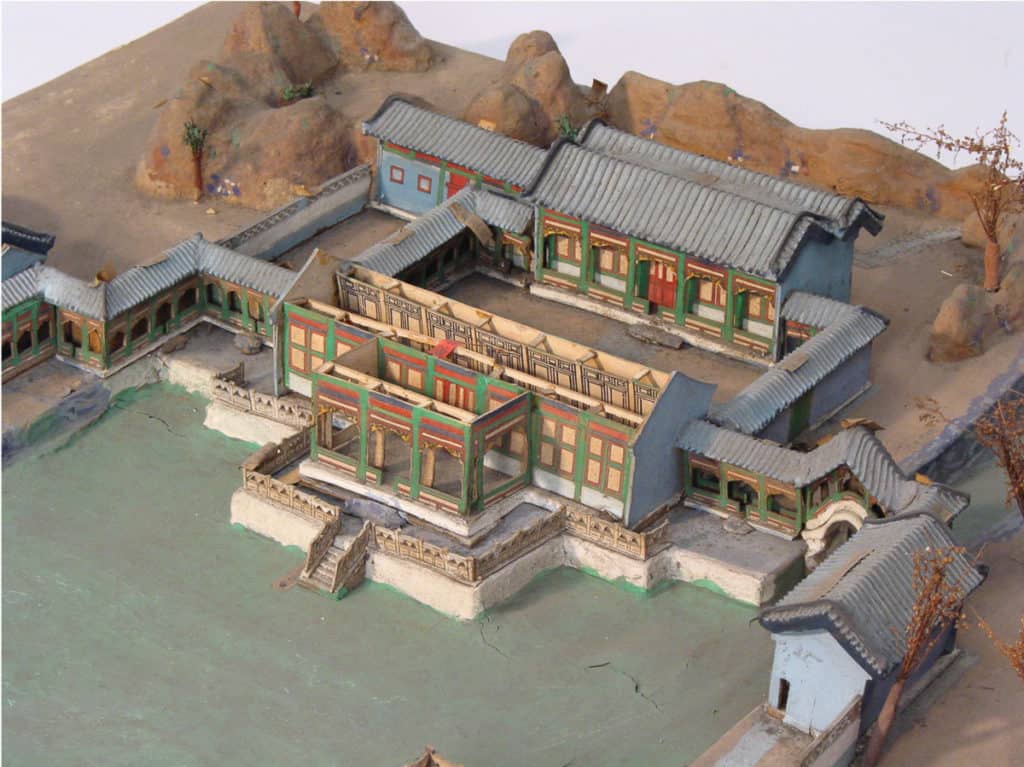

In 2000, when the restoration work began from the ground that was left un-tended for three-quarters of a century, there were hardly any records of an architectural plan from the original construction. Different from the Western discipline, architecture did not exist as a profession in imperial China and design was largely done by builders. Their intricate work embodied the “cosmic breath” belief. Generations of craftspersons balanced a wealth of craft knowledge with each emperor’s personal taste. These craftspersons mastered the structural characteristics of traditional buildings and could have assembled one without ground plans, scale drawings or written instructions. There was no surprise that no relevant records were archived, perhaps few existed in the first place. Apart from a couple of manuals written from early architectural historians, research for the restoration relied on limited photographs and paintings, and a tangyang, a scale model made of pinewood, paper and stalks, that was believed to be made for planning the Jianfu Palace and Garden construction.

An informal group of “old experts” were gathered to advise on the project and retired master craftsmen were brought in to teach apprentices about traditional building techniques. In this process of tracing some 250-year-old techniques, the reconstructed building would be crafted by the intangible heritage available today. Harun saw it as a “museum of Chinese architecture”. It was a reflection of the craftsmen, their crafts and a transmitter of that heritage. The five-year-long restoration involved communities of stonemasons, timber framers, terracotta factories, painters, technicians and advisors. There were many collaborations and negotiations involved in tracing historical methods and the current social context. Harun commented, “The authenticity is really in the process.” This project is a valuable case study in how to engage cultural communities in the safeguarding process, as specified in the UNESCO’s 2003 Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage (Article 15).

Stones

The reconstruction started with a debate on whether to save the existing 64 stone column plinths that ranged from intact if slightly eroded to endangered. For years, the stonemasons from Fangshan, carved stones supplier to the imperial palace since the fifteenth century, had been replacing what is incomplete with newly made pieces. Their reason was the importance of durability over originality. It took stone conservative expert John Sanday a decent amount of effort to prove that a special technological method of “saving” the stones could also achieve an outstanding level of durability.

Timber

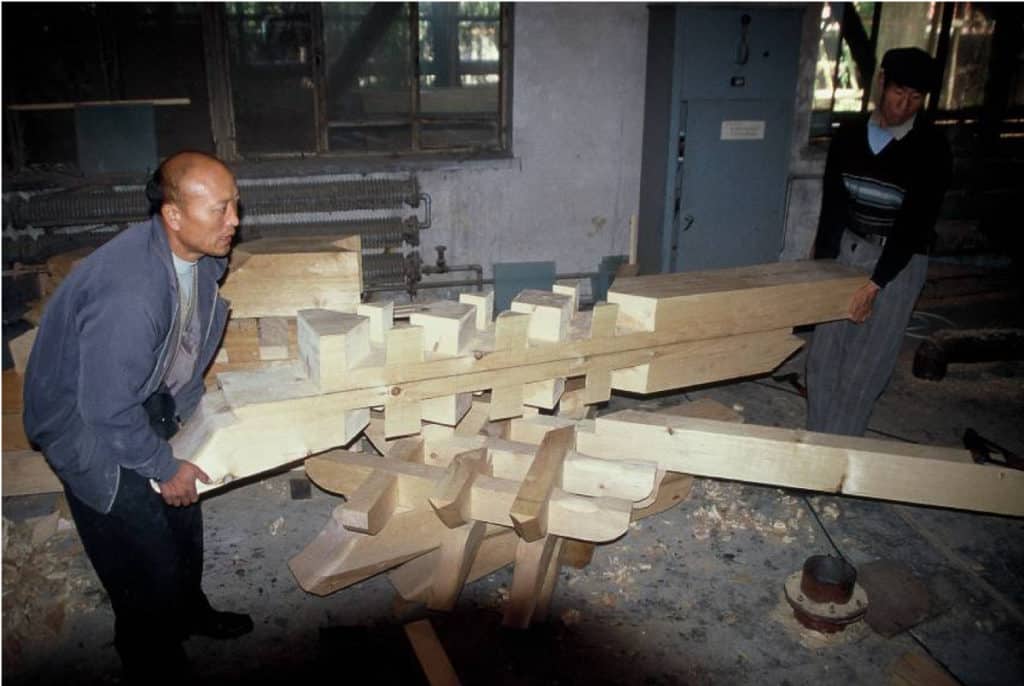

By contrast with the rigidness of stonework, the timber framing for traditional buildings is a highly flexible practice. The interlocking frame, organic in structure, is fitted together not with glue or nails but by means of mortise-and-tenon joints or dongong (bracketing system). The Pavilion of Prolonged Spring alone is composed of over 7000 separate timber members, each determined by structural necessity, cut and hand-finished with traditional tools in accordance with Ming-dynasty precedent. From the choice of wood to the ten-steps procedure of timber treatments, each requires consideration of material supply and seasons of the year. Since the original wood, nanmu, is no longer available in China, the team insisted on using local materials and the craft communities settled on a Korean pine. This woodcraft is still well-practised nowadays, however, there is generally no opportunity to construct on such a big scale. Older masters were excited to take on the challenge of such an ambitious project. Harun noted that a certain carpenter was “taking increasing pride in his work. He jots down notes and calculations, and said he wanted to see the project through”. Although the material choice raises concerns about originality, the community’s entitlement in the heritage safeguarding process has played a key part in keeping a genuine approach to this project. Unfortunately, little has been done to set up effective systems to engage craftspersons in the long-term after this large-scale restoration. Without consistent opportunities to practice and refine skills, it has proved difficult to keep carpenters in relevant trade and pass on their intangible heritage culture during China’s age of swift modernisation.

Terracotta and tiles

Another important component of the construction was the terracotta and tiles for roof and floor decorations. The change of social and labour structures in the country during the 50s and 60s resulted in a complicated regional enterprise set up, which indirectly contributed to the difficulty in quality control within the existing culture. In the case of the roof, the product used was not an imperial standard but the best quality available between a few sampled workshops. Meanwhile, the search for “golden bricks”, a type of floor tile used in the grandest pavilions in the Forbidden City, led the team to a factory named Yuyao, which means “Imperial Kiln”. Although it is not certain that the same factory supplied tiles for the original garden, searching for suitable suppliers of heritage components was a journey of weaving through old and new craft communities. I believe these contacts made with the eager factory owners reactivate connections to an ancient Chinese identity. I also believe that preserving historical monument could contribute to preserving social links through physical heritage constructions.

A state’s private garden

Harun mentioned towards the end of the restoration that she believed as long as the craftspersons and the crafts are alive, the garden can be rebuilt again and again. “The reconstruction was so hugely depended on the craftsmen, it was really their knowledge, their work and achievement…” She initially proposed to have the traditional tools displayed inside the pavilions to credit the craftsperson’s work and to mark this opportunity for their reconnection with professional and cultural roots. Involving the craft communities demonstrated that heritage is no longer understood purely as a “national treasure” but a social and cultural resource of those that create, maintain and transmit it, and can be directly identified with. Ironically, new regulations of craft engagement for heritage conservation has been formed and implemented in China since this inaugural project, indirectly marginalising existing “informal” craft experts in “official” projects and in some cases excluding accessible authentic heritage building methods such as with bans on ingredient use.

It was eventually decided that the restored garden would be renovated so that the pavilions’ interior could be used for receptions and as an exhibiting gallery. Gathering in experts from the globe, CHF created an air-conditioned, sound-proofed contemporary space, incorporating new technologies in order to hide all the modern machinery within an ancient-styled architecture. While the topic of authenticity emerged again, Harun responded, “If Qianlong had access to air-con, he would have put it in too. This building needs a toilet and air-conditioning to host modern-day guests”. It is clear now that the restored garden will remain a private space, for diplomacy and nation-building purposes.

In 2009, the Garden was handed over to the management of the museum and the interior of the pavilions have adapted to the taste of decision-makers at the time and the preparation of any given important event. It has remained closed access and recorded publicly only with occasional receptions of ambassadors and ministers of states, such as US President Donald Trump in 2017.

The journey through the restoration of the magnificent Jianfu Palace Garden has provided an opportunity to uncover old and strengthen current social bonds with craftspersons. An example of an interpretation of the past and the present, the restored garden now stands as a product of the cultural context between the 1990s and early 2000. As China continues to develop rapidly, the call for preservation and empowerment of declining intangible heritage crafts is vital for safeguarding authenticity in heritage conservation.

Bibliography

Blake, J. (2018). Museums and Safeguarding Intangible Cultural. Heritage – Facilitating Participation and Strengthening their Function in Society. International Journal of Intangible Heritage, 13, pp.17-32.

British Museum. (2019). Nüshi zhen tu 女史箴图 (Admonitions of the Instructress to the Court Ladies) / The Admonitions Scroll. [online] [Accessed 2 Jan. 2019].

Doar, B. (2005). The Transition from Palace to Museum: The Palace Museum’s Prehistory and Republican Years. [online] China Heritage Quarterly. [Accessed 31 Dec. 2018].

Evans, H. and Rowlands, M. (2014). Reconceptualizing Heritage in China: Museums, Development and the Shifting Dynamics of Power. In: P. Basu and W. Modest, ed., Museums, Heritage and International Development, 1st ed. New York: Routledge, pp.272-294.

Harun, H. (2018). The Palace of Established Happiness: Restoring a Garden in the Forbidden City.

Holdsworth, M. (2008). The Palace of Established Happiness. Beijing: Forbidden City Publishing House.

Jones, S. and Yarrow, T. (2013). Crafting authenticity: An ethnography of conservation practice. Journal of Material Culture, 18(1), pp.3-26.

Palace Museum. (2019). 建福宫花园 – 故宫博物院. [online] The Palace Museum. [Accessed 1 Jan. 2019].

Puyi. A. and Jenner, W. (1964). From Emperor to Citizen: the autobiography of Aisin-Gioro Pu Yi. Peking: Foreign Language Press, pp.132-136.

Tomczak, M. (2017). Is China a Model Member State of UNESCO in Implementing the 2003 Convention? Reasons, Benefits, and Criticisms. Santander Art and Culture Law Review, (2), pp.297-318.

TsAO & McKOWN. (2019). Jianfu Palace Museum. [online] [Accessed 2 Jan. 2019].

UNESCO. (2003). Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage.

UNESCO World Heritage List. (2019). Imperial Palaces of the Ming and Qing Dynasties in Beijing and Shenyang. [online] [Accessed 2 Jan. 2019].

Wang, S. and Rowlands, M. (2017). Making and Unmaking Heritage Value in China. In: J. Anderson and H. Geismar, ed., The Routledge Companion to Cultural Property. New York: Routledge, pp.258-276.

Wang, S. (2017). Exhibiting the Nation Cultural Flows, Transnational Exchanges, and the Development of Museums in Japan and China, 1900-1950. In: C. Stolte, Y. Kikuchi, A. Esposito and M. Herzfeld, ed., Eurasian Encounters: Museums, Missions, Modernities. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, pp.47-72.

Author

Sharon Tsang-de Lyster is a heritage, textile and design trends researcher. She is the founder of design studio Narrative Made and award-winning resource platform The Textile Atlas, which champions intangible heritage conservation and sustainable sourcing through documenting and network building for textile making practices. Building on her experience and knowledge in handmade textiles, sustainable production and journalism, Sharon is known for her considered and stylistic approach in bringing artisanship to the international stage. Her work has been showcased at global fashion weeks and design weeks and featured by international media.

Sharon Tsang-de Lyster is a heritage, textile and design trends researcher. She is the founder of design studio Narrative Made and award-winning resource platform The Textile Atlas, which champions intangible heritage conservation and sustainable sourcing through documenting and network building for textile making practices. Building on her experience and knowledge in handmade textiles, sustainable production and journalism, Sharon is known for her considered and stylistic approach in bringing artisanship to the international stage. Her work has been showcased at global fashion weeks and design weeks and featured by international media.

Comments

vqw0xd