Artists in the Ancient Now online exhibition were invited to send an image of their work along with a reference from the deep past. Their thoughtful works provide a conduit between the ancient and contemporary worlds.

The past, present and future is always with us. The era we see depends on what we choose to focus on. Earlier this year, walking the hectic streets of Hong Kong, I found myself under a busy freeway overpass. A group of elderly women caught my eye. They had set themselves up in the cramped, darkened space, offering traditional Chinese facial readings. Based on ancient Taoist principles, it seemed they were barely making a living from keeping this knowledge alive. In a highly consumerist, decolonised city, now finding itself again as a Chinese territory, it was disheartening to see these traditional practices marginalised. It made me question where do these traditional Chinese practices belong?

In the broader Chinese context, the relationship between the “ancient” and the “now” is fractured, constantly being negotiated and transforming in the contemporary age, particularly with the rapid rate of change in mainland China. In recent years, Confucian philosophy, which was once rejected, is now officially endorsed to help guide China’s moral compass into the future. As an Australian of the Chinese diaspora, I consider myself a life-long learner of Chinese art and culture, attempting to navigate through the complex layers of politics, language, cultural regional differences and various generational outlooks. It fascinates me that certain aspects of traditional Chinese culture are only preserved and practised outside of China, migrating with communities who responded to the overwhelming social changes in China over the last century.

In considering how our relationship to “ancient” knowledge is fluctuating and mutable, the selection of artists in this exhibition, give us an insight into a global community of practitioners, who continually negotiate and renegotiate meaning through an ancient lens. The artists demonstrate how ancient technologies, methods, cultural myths and philosophical outlooks continue to inspire conversations in their practices and perhaps offer new and personal insights into an aspect of the “ancient”, which we could also learn from in the “now”.

Tammy Wong Hulbert

Artists

Andrea Wagner | Benjamin Sheppard | Gayle Fichtinger | Georgiy Margvelashvili | Shirley Bhatnagar | Revati Jayakrishnan | Ishan Khosla | Vinod Prajapati | Maree Clarke | Pamela See | Pattie Beerens | Paul Leathers | Pie Bolton | Robyn Phelan | Terry Martin | Ye Liu

Terry Martin and Yu Zhongyong

Brisbane, Australia, and Huangshan, China

Terry Martin and Yu Zhongyong, Feng Shui Cyclops, 2014, boxwood and acrylics, 18cm H X 9cm X 7cm, photo Terry Martin

Inspired by the ancient village of HuangShan where I saw ancient Feng Shui structures, my friend Yu Zhongyong proposed we work to make a piece encompassing these principles: in Australia I carved a Cyclops with six limbs to represent the aspects of Feng Shui (Heaven, Earth, People, Energy, Spirit and Mind) and after I sent it to him in China he applied a 5000-year-old Feng Shui compass to complete the collaboration.

Shirley Bhatnagar | Revati Jayakrishnan | Ishan Khosla | Vinod Prajapati

Delhi, India

Shirley Bhatnagar | Revati Jayakrishnan | Ishan Khosla | Vinod Prajapati, Unearth, 2017, Stoneware with Manganese Oxide decoration 14.5x15x15 cm, photo: Ishan Khosla.

The project is inspired by the potsherds from the Indus Valley Civilisation (IVC). The sherds used in the work and the forms and profiles created are referenced from actual Harappan painted pottery with its polychrome geometrical and floral designs. While we have taken direct references from the IVC, we have resized the objects for contemporary use. Archeologists use pottery sherds and try to recreate the original form. We have tried to piece a puzzle of an ancient civilisation by reinterpreting some of the sherds found in digs. These have been pieced together into functional objects giving the appearance of a pot emerging out of a dig. Additionally, the physical gesture of “the dig”, or unearthing an ancient find is similar to digging the Earth to collect clay which is then used to make pottery. Indeed, many finds have been made in this unintentional manner.

f Shirley Bhatnagar | f Ishan Khosla | f Revati Jayakrishnan | f Vinod Prajapati

i @shirleybhatnagar | i @rare_studios_india | i @indiakangaroo | i @thetypecraftinitiative | i @vinodclay

Robyn Phelan

Robyn Phelan, Depleted, 2011, Southern Ice Paper Clay, cobalt glaze, h. 35cm, w. & d. variable, photo: Christopher Sanders

Depleted is a series of sculptural vessels made after a residency in Jingdezhen, China in 2008. The work is a metaphor for the environmental devastation caused by kaolin mining, a result of Europe’s obsession with blue and white porcelain in the 16th century.

Jingdezhen porcelain was poetically known to ring like a resonant bell, be white as jade, as thin as a sheet of paper and as bright as the mirror. This material was like gold in comparison to Europe’s indigenous earthenware clays.

Studio artists at the Pottery Workshop, Jingdezhen are taken on tours of local ceramic heritage sites. Once such tour is to see the ‘remains’ of Mount Gaolin, named after ‘kaolin’ the magical mineral unique to porcelain production in this region. Expecting to see romantic mountains depicted in scroll paintings, I was confronted by a landscape that resembles a bomb site with spartan plantings by local villagers to stop the what remains of the mountain from eroding away.

Andrea Wagner

This work was made for the exhibition The Palace of Shattered Vessels: Chinese Porcelain and Contemporary Jewelry. 39 leading international artists were given each a few shards of ancient Chinese porcelain vessels, to create their own unique jewel.

Maree Clarke

Installation view of Maree Clarke, Ancestral Memory, 2019, glass (blown at Canberra Glassworks), photo: Christian Capurro

Installation view of Maree Clarke, Ancestral Memory, 2019, glass (blown at Canberra Glassworks), photo: Christian Capurro

Ancestral Memory tells the story of water on the lands of the Kulin Nation. Displayed a the Quad Gallery, University of Melbourne, alongside two woven eel traps, the distinctive patterns and methods of weaving connect these items to place; to a series of waterways running thick with eels and ancestral memory. According to Jeff Greenaway, “the eels continue to swim through the storm water pipes of the University. They rear their heads up in some of the ponds and stormwater grates that exist on the campus.”

Benjamin Sheppard

Melbourne

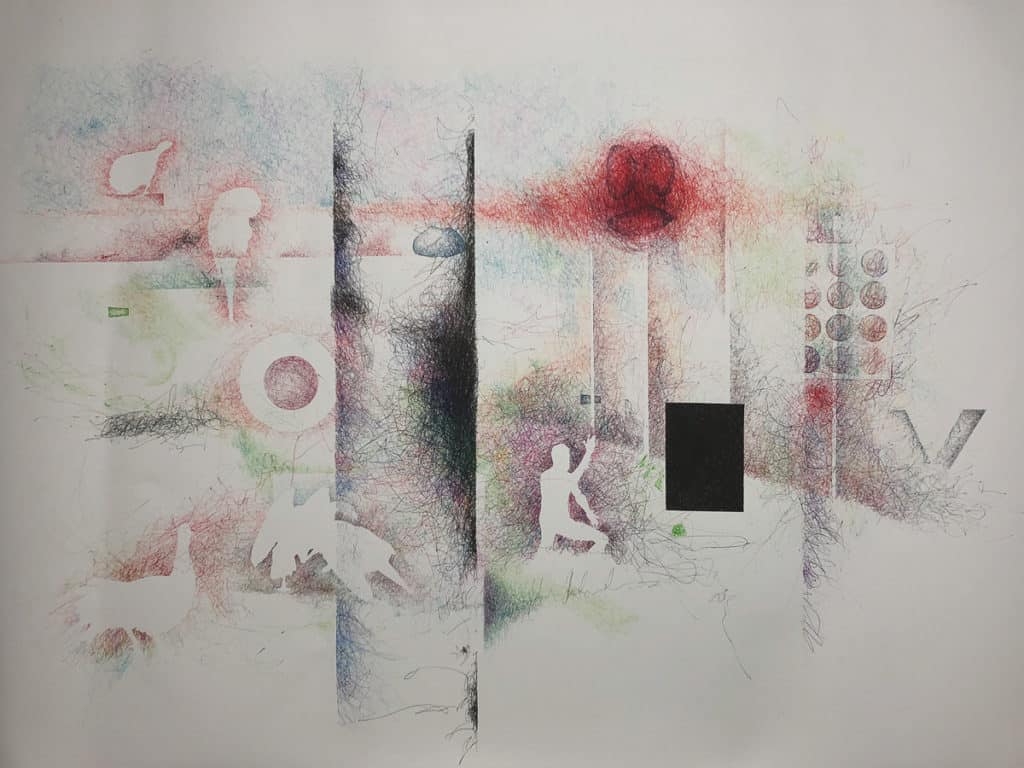

The work is part of a practice-based PhD project which reconsiders Australian national identity using contemporary drawing – reframing it as a ‘work in progress’. As part of a broad body of work, this drawing will, ostensibly, never be finished.

Gayle Fichtinger

Savannah, Georgia, USA

Hand-built in red stoneware clay, this sculpture is the outcome of intensive nature study in New England and travel to China to study scholar stones and Yixing ceramics.

f www.savannahclaycommunity.com/gayle-fichtinger.html

Pattie Beerens

Melbourne, Australia

The work was an exploration of place reflecting on 4000 years post the Minoan civilisation.

Ye LIU

University of New South Wales in Sydney

Ye LIU, New Order, 2018, Materials: Clay, Branches, Grass, Tiles; Dimensions:3300mm x 2100mm x 400mm; photo: Ye LIU

The ‘New Order’ is a living installation created by Ye LIU who comes from China, inspired by the myth of the Phoenix Nirvana rising from the ashes, it describes a new scene of death and rebirth as well Ye’s view of the new order of culture in modern China.

Pie Bolton

China (Jingdezhen) and Australia (Melbourne)

Pie Bolton, 2016, Influence, JDZ porcelain, Southern Ice porcelain, oxide, stain, red cord, multiple firings, dimensions 360 x 240 x 100mm, Image Mick Bell

The work was made in response to a ceramic residency in Jingdezhen combining ancient technique with contemporary form and is called ‘Influence’ because it was commenced in China with Australian influence and completed in Australia with Chinese influence.

Pamela See (Xue Mei-Ling)

Australia

The Day After Tomorrow is a series of papercuts examining enduring species of flora an fauna including jellyfish and snails. This particular composition features cicada and a bonsai tree which may be interpreted as symbols of rebirth and longevity. I am an Australian artist of Chinese descent.

Yiwon Park

Seoul, Korea

My work about the Pacific ocean delves into my feeling of insecurity caused by my physical displacement from my birthplace, Korea. It forms part of a larger series of work titled ‘My own Pacific ocean’ that formed my own ritualised creative response to place and its impact on my sense of identity. The Pacific Ocean, the physical boundary between Korea and Australia, defines my geographical and cultural identity, identifiable as a specific geographic entity, yet, being comprised of water, simultaneously formless and in a perpetual state of flux. Also, in Korean belief systems, water represents the boundary between the mortal world and afterlife. Water and ritual have become significant aspects of my practice since my parents passed away.

Georgiy (George) Margvelashvili

Australia (Melbourne)

Georgiy (George) Margvelashvili, In Search of the Logos, 2018, oil and wax on canvas, 130 x 85 cm, photo by Georgiy Margvelashvili.

My work examines stone and metal statues as vessels for storing information, as signifiers which can be re-purposed for other content.

w https://www.instagram.com/georgiy_m_art/

Paul Leathers

Red Deer, Alberta, Canada

Paul Leathers, JDZ (Blue & White; 3DP) Fragment Brooch, 2019, Sterling silver with cabochon-cut moonstone and dyed 3D printed nylon form. 5.2 x 6.0 x 0.8 cm, photo: paul leathers

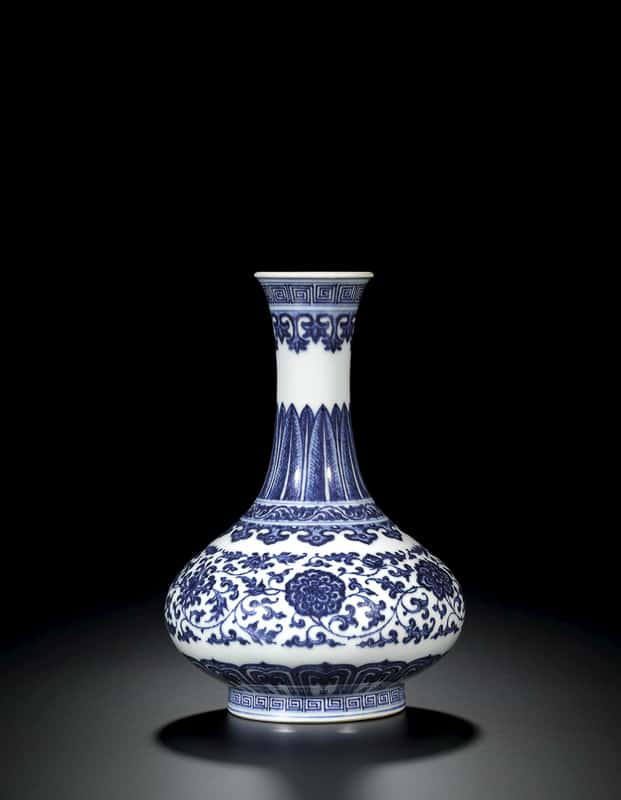

Blue and white pear-shaped vase, Mark and period of Qianlong (1736-1795); 20.3 cm. Photo: Sotheby’s

This brooch, entitled JDZ Fragment (Blue & White; 3DP), capitalises on my participation in a number of artist residencies—exciting opportunities for taking a perpendicular stance to one’s studio routines—at The Pottery Workshop in Jingdezhen, China, the historical home of porcelain. There, orthoclase feldspar (moonstone) is used as one of the main components of porcelain clay bodies and glazes. Over the past decade, I have been immersed in both contemporary and ancient Blue & White ware and have been inspired by the fresh hand of the cobalt underglaze painters of the Qing dynasty. Fragmentary shards of especially beautifully-painted pieces are often set in silver, blending the ancient and contemporary together, and worn as pendants or brooches.

This brooch, too, develops a dialogue between past and future. Having co-led a master class focusing on emergent digital technology for ceramic design in Jingdezhen (Spring, 2017), I decided to consolidate my experiences and impressions in this artwork. Turning to dyed 3D printed nylon was a necessary solution to the fragile nature of my earlier coloured porcelain versions and allows for an increase in the scale of what might otherwise have been a prohibitively heavy brooch. For me, the use of digital technologies in my studio practice opens up exciting new pathways for thinking about material and form.

Comments

Beautiful show. Satisfying and inspiring. Thank you for putting it together.