Beverley Price, Nespresso necklace with a return ticket to Munich, Nespresso Capsules, wire, air ticket

Beverley Price explains the creative principle of her expedited jewellery and how it is grounded in South African life.

(A message to the reader.)

The words “emergency” and “urgency” evoke immediate action. “Emergency” is redolent of saving lives, but I will work with the word “urgency”. It means taking action in response to a drive or impulse, or an obligatory reaction to an internal or external stimulus, where time may be limited.

An urge is a strong desire to act and informs the word “urgency”.

In planning the Urgent Adornment workshop, I wanted to offer my jewellery colleagues an opportunity to make art under pressure. When I visit my dentist, I tell him this is what he does. He finishes a (mostly) perfect creation in the designated time of my appointment.

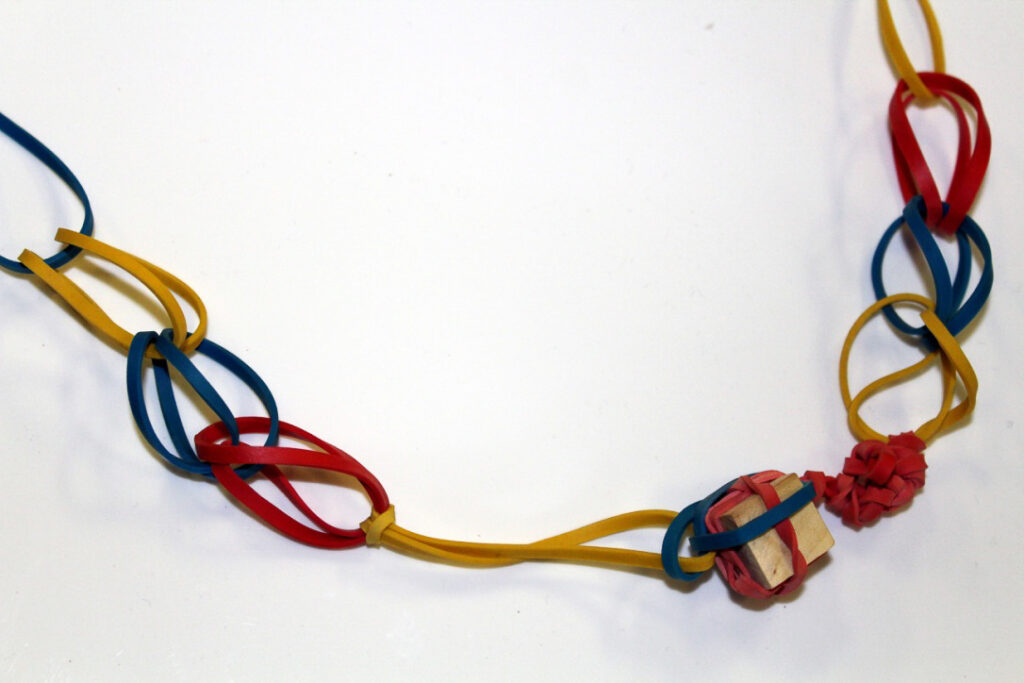

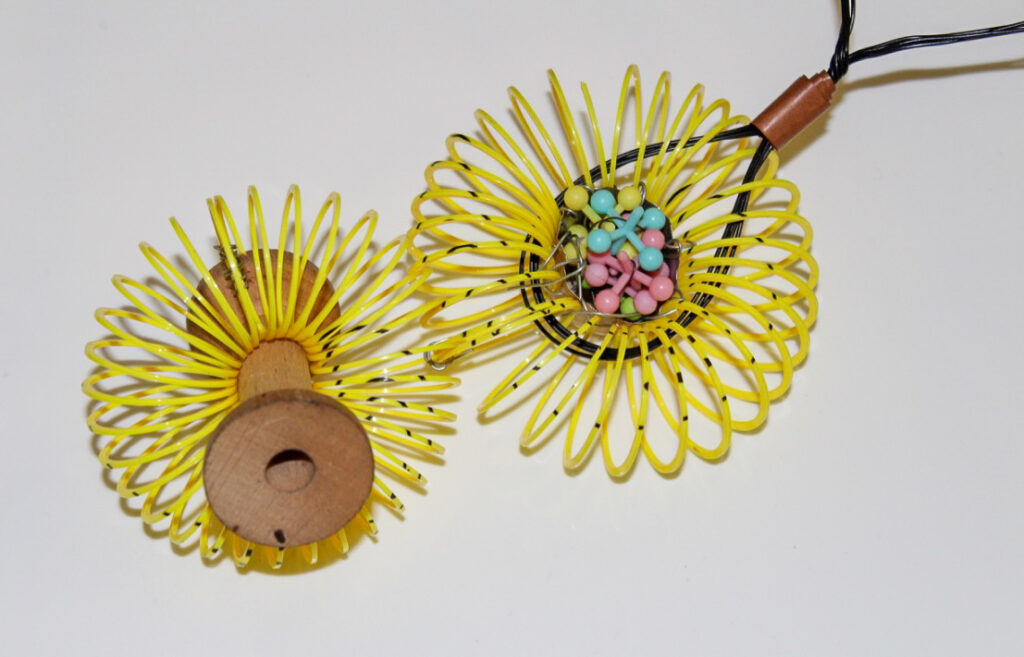

I explained to my colleagues that Urgent Adornment meant that we were going to make pieces of jewellery in a limited time (two hours) with limited kinds of materials (no gold or silver) and with limited jewellery techniques (no soldering). The permitted joining methods would be cold only, including using safety pins, elastic bands, wire, glue and staples. A pendant drill was available.

My intention was that the participants “mine their minds” to reveal new creativity under a situation of pressure. Without the security of using gold or silver, we would have to circumvent our pre-ordained, conditioned and secure ways of attributing value to our pieces of jewellery.

Fifteen people participated at the University of Johannesburg Jewellery School. They were required to forage for materials for a week before the workshop, gathering materials of no intrinsic value and which caught their eye. These included wood, plastic, wire etc. and they were to bring them on the day. They could also avail themselves at the workshop, of a “smorgasbord” of my materials collected over many years.

Works from the Urgent Adornment workshop, displayed at Tinsel Gallery:

Urge and Urgency

I hypothesised that during the week of collecting, their curiosity would be piqued and the urge for using their materials in a particular way would brew in the jewellers’ minds, giving rise to an excited impatience to make their pieces.

At the workshop, they were aware of the urgency to complete something wearable, from scratch in the limited time available. There was also the awareness that it was a once-off special opportunity to share this group dynamic as professional jewellers—a chance to play, experiment and find new languages and logic in a supportive and minimally competitive environment.

On completion, we laid out our pieces for viewing, stood around and each person talked about their work. Eric Loubser, who with Geraldine Fenn owns Tinsel Contemporary Jewellery Gallery in Johannesburg, said he had not seen such fresh and creative work in South Africa for years. I think people had a cathartic experience and felt freedom to express themselves which might spawn new ideas or give permissions to themselves for new jewellery aesthetics and forms.

Motive and History

For many years I have worked with non-precious found materials in my jewellery adornment pieces, including vinyl records, sausage paper and disposed Nespresso capsules. After completing my jewellery training in Israel and the UK, I returned to post-Apartheid South Africa in 1995 and lived for three years in a rural part of Zulu-speaking KwaZulu Natal. I was exposed to Zulu cultural adornment objects and practices and experimented with intrinsically non-precious materials.

Returning to live in Johannesburg I studied at the Wits School of Arts. I was encouraged to make very large adornment objects seeking a Western-African hybrid aesthetic. The Wits Art Collection, now known as the Wits Art Museum, impacted on my thinking and I saw many indigenous-cultural ritual adornment objects of diverse scale, from expansive Ndebele marriage capes (over a metre wide) to Zulu love-letters worn on the neck. These are made with such integrity. I was impressed by the precise beading on leather and how the forms are transmitted from one generation to the next. Post-apartheid, these objects began to be collected as fine art rather than as previously called, “primitive–tribal craft”.

Western-type materials were, in many instances, incorporated into the objects, namely plastic tablecloths, car number-plates, test-tube bottles and buttons. The Wits publication Engaging Modernities is a good reference source for this. It would appear that the makers had a fascination with Western materials taken out of context (South Africans lived as separated races) and away from their original cultural uses. Exoticising the materials, the makers attributed new value and found ways to improvise with the materials and substitute for their conventional use of beads.

It may, however, have been that their inventiveness arose under time pressure due to the urgency of a deadline to create a ritual object for an upcoming ceremony. It is this urgency which I chose to regard as pivotal and which I wished to awaken in my colleagues.

Africans have been using all kinds of materials to adorn themselves for millennia (see cave story and shell adornment). The first-ever adorner of the human body lived on the African continent, a middle-Paleolithic person, approximately 300,000 years ago. At the Blombos Caves in South Africa engraved ochre and bead-like ostrich shells were found and interpreted to be an indication of early human symbolic expression akin to verbal language. This phylogenetic, cognitive shift of transforming a material and placing it on the body (not using the material as clothing) for a semiotic purpose, happened in Africa. It may have aroused sheer delight for its maker or if worn in the community, been mimicked and invested with amuletic significance perhaps of luck for hunting, or for finding a mate.

In the Urgent Adornment workshop I wondered at the possibility to arouse under pressure, an ancient “adornment fractal” in our jewellers, given that all of us grew up surrounded by ancient and entrenched African cultural adornment practices, some more than others, whether urban or rurally exposed.

During the times that I exhibited at Schmuck Sonderschau in the 2000s, I saw that Europeans frequently deploy intrinsically non-precious materials. Often the jewellery objects seemed to abnegate jewellery as a social practice or present an apology. It was a kind of nihilism, an intelligent rebellion against conventional jewellery-material indulgences. Africans have been handling, tooling and delving into materials for hundreds of thousands of years, creating the oldest adornment practices known to man. Africans have much to teach Europe in the matter of improvisation and innovation with materials and with an attitude of delight.

As South African jewellers, however, we need to first activate these valuable nuggets within ourselves. That was my motive for this workshop.

Author

I am a first-generation Jewish South African and lived in Israel and the UK. Returning to SA, I trained 4 women in my jewellery techniques to earn from the work. In my work, I reference the Mapungubwe precolonial history of South African Gold, the South African indigenous adornment practices and also my commitment to Jewellery art as a robust fine art medium, out of the hermetic safety of exclusively jewellery art contexts. Two of my highlights are meeting Nelson Mandela and seeing a 500-gram fine gold piece I made worn on a beautiful black model. I have exhibited a lot in and out of South Africa, and my sculpture and jewellery are collected in the US, UK, Europe and Australia. My thinking is also informed by studies of accessible Jewish mysticism. Corona permitting, I will be occupied for a few months restoring the largest Judaica silver collection in South Africa. I am currently working on a pair of plique a jour enamel earrings. (See YouTube channel)

I am a first-generation Jewish South African and lived in Israel and the UK. Returning to SA, I trained 4 women in my jewellery techniques to earn from the work. In my work, I reference the Mapungubwe precolonial history of South African Gold, the South African indigenous adornment practices and also my commitment to Jewellery art as a robust fine art medium, out of the hermetic safety of exclusively jewellery art contexts. Two of my highlights are meeting Nelson Mandela and seeing a 500-gram fine gold piece I made worn on a beautiful black model. I have exhibited a lot in and out of South Africa, and my sculpture and jewellery are collected in the US, UK, Europe and Australia. My thinking is also informed by studies of accessible Jewish mysticism. Corona permitting, I will be occupied for a few months restoring the largest Judaica silver collection in South Africa. I am currently working on a pair of plique a jour enamel earrings. (See YouTube channel)

Comments

This is so inspiring. I have see inventiveness in ritual object making in my own home and never thought of studying it at an academic or professional level. I would like to harp upon this challenge with a different set of restrictions to see what the output it.