- Sitaben Chavda

- Garland by Sitaben Chavda

LOkesh Ghai interviews artisans and finds there is more to consider than the immediate problem. This includes challenges but also a Garland of Hope and Wisdom.

(A message to the reader.)

As the Covid-19 pandemic hit, many migrants returned to their villages, but would they consider staying instead of returning to the city slums once the pandemic subsided? Would they return to crafts? With over 200 million people involved, the craft sector is India’s second-largest employer after agriculture. Artisans make up a large proportion of this sector, but with many living in villages, there has been a growing number leaving their traditional livelihoods to migrate to cities for better opportunities. A recent UN report revealing that over 30 years the number of artisans working in India’s craft sector has decreased by 30%. Most of the published articles discussing the impact of Covid-19 on the craft sector are advocating for cheaper manufacturing. This article proposes an alternative direction for the sector. It presents the voice of the grassroots artisans, allowing them to raise their own concerns and propose a possible way forward.

Perception of craft and craftsperson

- Shanti Devi Bora

- Stole by Shanti Devi

“Handweaving was strongly discouraged. There was a general consensus within the Bora community that we did not progress because we continued weaving traditional products such as the bora (sack bag) and budla (covering)!” Since generations, Bora community has been making hand-woven sack bags and floor coverings, perceived as menial products. For many years, Shanti Devi Bora preferred part-time construction labour over weaving, but more recently she came across a good opportunity to return to the practice of weaving with the organization AVANI. Operating with a decentralized model that focuses on sustainability, unlike many other handloom centres in India who rely on raw materials from China, AVANI uses locally grown materials. All the textiles produced by the artisans they work with are handwoven and everything is authentically naturally dyed. Shanti Devi is happy: she makes an honest living and is able to stay in her remote village amongst the hills. Good livelihood is not equal to more work, but work that would pay more and is dignified. I hope those eager to help artisans would consider this.

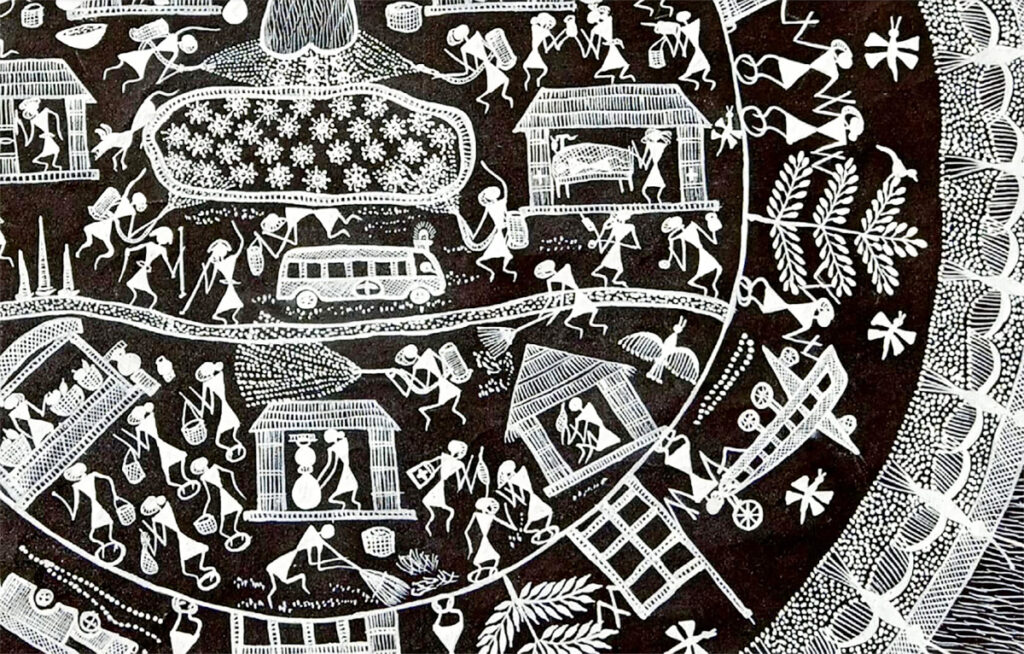

Late Jivya Mase warli artist

A design student embarking on his graduation project approached me asking if I knew any Rabari embroiderers who would embellish fabric for him, stating that it “would be a help to the artisan,” as he would “bring work to her.” This student’s approach to his graduation project is echoed by many designers across India and internationally. The embroidery design was not discussed with the artisan nor would she be acknowledged for her work on the embroidery in the final piece. The student just assumed, with power differentiation, that the artisan was a labourer. The designer would get his work done and in achieving this would also often exploit the aesthetic style of the ethnic group. In India appropriation is not yet even a debate. Padma Shri, late Jivya Soma Mashe, was quite clear in a conversation with me: “We do not mind if anyone copies Warli art. Just don’t call it Warli; give it any other name. We are Warli people, it is our art.”

Returning to the idea of providing more work to the artisan, I asked the student if once he has graduated and had started earning a salary, after ten years of work experience, would he like his boss to provide him with a better salary to match his experience or more work? “Obviously a better salary,” he responded. An artisan is not a machine, he or she could work 12 hours a day, and that may be their human capacity, but it is better pay that they would hope for as they gained experience, not more hours of work. The world beyond academic learning is not much different.

One of the biggest handcraft store chains in India works on the principle of producing huge quantities of handcrafted goods, with their profits increased by bargaining lower profit margins for the artisans who make the products they stock. Unfortunately, such models push marginalised craftspeople further into the margins. Machines are not involved in what is genuinely handmade, therefore (even when the quantity is more) it takes the same amount of time, energy and materials to make each product. Asking for discounts would mean compromising with quality and lower earnings for the real artisan maker.

Power play

- Bashirbhai Khatri

- Sari by Bashir bhai Khati

From Bhuj, Basirbhai Khatri, a bandhani artisan, explains the two kinds of people who have emerged during the Covid-19 crisis: one supporting daily wage artisans, and the other exploiting them. “Our craft works through a chain of artisans; usually women tying the fabric and men doing the dying. There are some who are pressuring artisans to take up tying at a much lower wage than usual.”

I asked a textile scholar conducting her PhD fieldwork on artisans if she would consider writing about class differences in the craft community, but my request was met with silence as she explained: “Those gaps should never be mentioned! It would make those at the top unhappy.” When tourists flock to a particular house in the village, and when urban patrons of craft appeal only to help that one family, they become so mighty that a thousand other artisans remain invisible. Unfortunately, relief funds would probably go to that one family, filtering marginally, if at all, to other artisans around them.

Possibilities

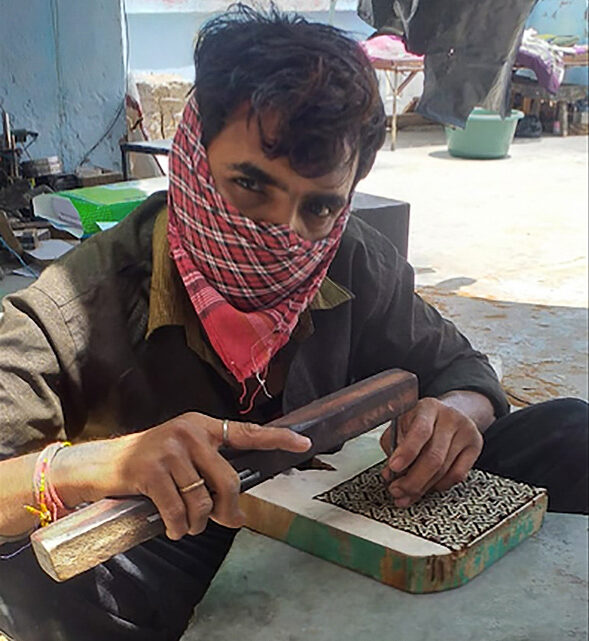

- Batik Art Shakil Ahmed Khatri

- Shakil Ahmed Khatri

Of course, not all master artisans are alike. Batik artisan Shakil Ahmed Khatri, from Mundra, shares that he pays full salaries to the artisans working at his studio seeing it as his moral responsibility to take care of those working for him. Many artisans are also volunteering as relief workers.

- Bharatbhai Jepar

- Long Kaftan by Bharat bhai

Bharat Jepar, a weaver from Varnora, Kutch, has been spending a few hours daily in relief work and the rest of his time weaving. In a telephone conversation, Bharat bhai expressed his concern: “I only have limited yarn. If the lockdown continues, I don’t know what I will weave.” I suggested that he not use his limited yarn to weave something regular but to use the limited raw material he has to weave something very special that could fetch a higher price. “That is the strength of craft. Each sari could be different even within the same warp, so many possibilities exist. That is what the machine cannot do – the creativity of the mind” explains Judy Frater, Founder Director of Somaiya Kala Vidya (SKV), who advocates design education as a solution to bridge the division between art and labour.

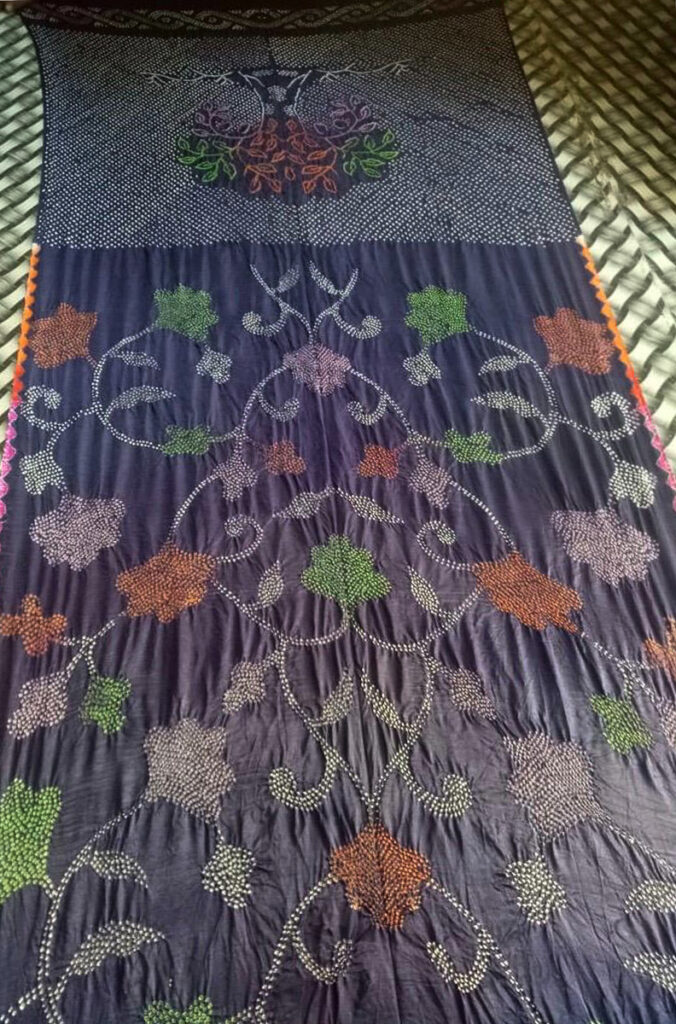

- Bandhani by Adil Khatri

- Adil Khatri

Adil Khatri, a traditional bandhani artisan reveals that he is using his limited resources and ample time during lockdown to design new samples based on Islamic architecture. “Although at present I cannot employ women for the tying of dots, I have stencils at home which I am utilizing to make new design drafts.”

Mental and Emotional Wellbeing

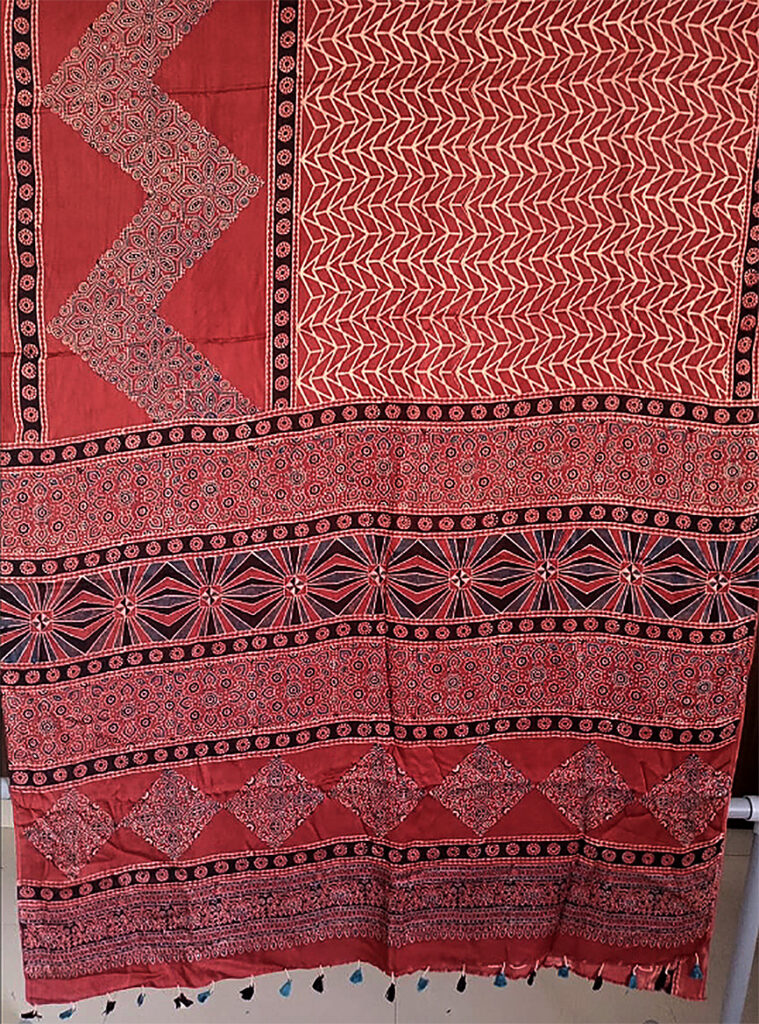

- Juned Husem Khatri

- Sari by Juned Husen Khatri

Juned Husen Khatri, an Ajrakh block printer compares the Covid-19 pandemic to the 2001 Kutch earthquake. He has a humble workshop where he works with his brother: “Our work has hugely suffered. I live in fear of the unknown. Even if the lockdown opens, the virus would not immediately end. I just hope nothing worse happens. I learnt during my education at SKV if plan ‘A’ does not work, think of plan ‘B’, so I am planning to utilise my time to carve new designs.” Maniram, a block maker form Ahmedabad is also carving blocks from home: “What is the point in sitting idle, even if I do not have orders my son and I can carve new patterns.” Shakil bhai is also using his time at home to learn the skills of stitching and painting on fabric. Basir bhai, shares that he does daily sketching first thing in the morning. He finds sketching a tool for mental well-being adding that the real joy will be when the lockdown opens and he is able to convert his designs into actual textiles.

- Katab by Vaishaliben

- Vaishaliben

Craft certainly has the power to express emotions and working with both the heart and hands is important for mental well being. This is a crucially important issue for craft communities during the Covid-19 pandemic. During the first lockdown, Vaishaliben, an applique artisan from Vadaj, Ahmedabad shared her anger: “When I went to the market, the shop keeper was extremely rude to me. I was made to stand at a far distance from where I had to shout what I wanted to purchase.” She went on to explain: “In the name of social distancing he was making fun of me. I felt demeaned as if I was untouchable or outcast. I would like to make a quilt on the subject of social distancing during the lockdown and how people stand at a distance.” In the second lockdown, her sister Rashmi narrated her concerns of food crises: “We were getting dinner from the Gurudwara during the first lockdown; it stopped in the second. No sugar or tea is available; tomatoes have risen from Rs 20 to 120/ kg. All my savings have finished. I am emotionally broken.”

Amitbhai Maniram’s son

Bead artisan Sitaben Chavda, from Ahmedabad old city, is also concerned about food: “I could somehow manage during the initial lockdown, but things are hard for me now, and if the lockdown continues, I will not be able to have two meals a day. AMC workers responsible for picking up garbage are not coming to my street. We have to clean the street and walk to the main road for garbage collection. It is hard for a senior citizen like me.” Sitaben has a few necklaces in stock, but no raw materials to use except very tiny Italian beads which she was avoiding using due to her weak eyesight. She is now threading these to make an elaborate necklace, which she calls a garland. “It could be worn in a classical dance performance, in a festival such as Navratri, or for any special occasion. It’s inspired by the women of Rathwa tribe. I made something like this long ago, what was old will be new fashion. I think I am making this garland after 30 years.”

A way forward through the clouds of uncertainty

- Anwarbhai Khatri

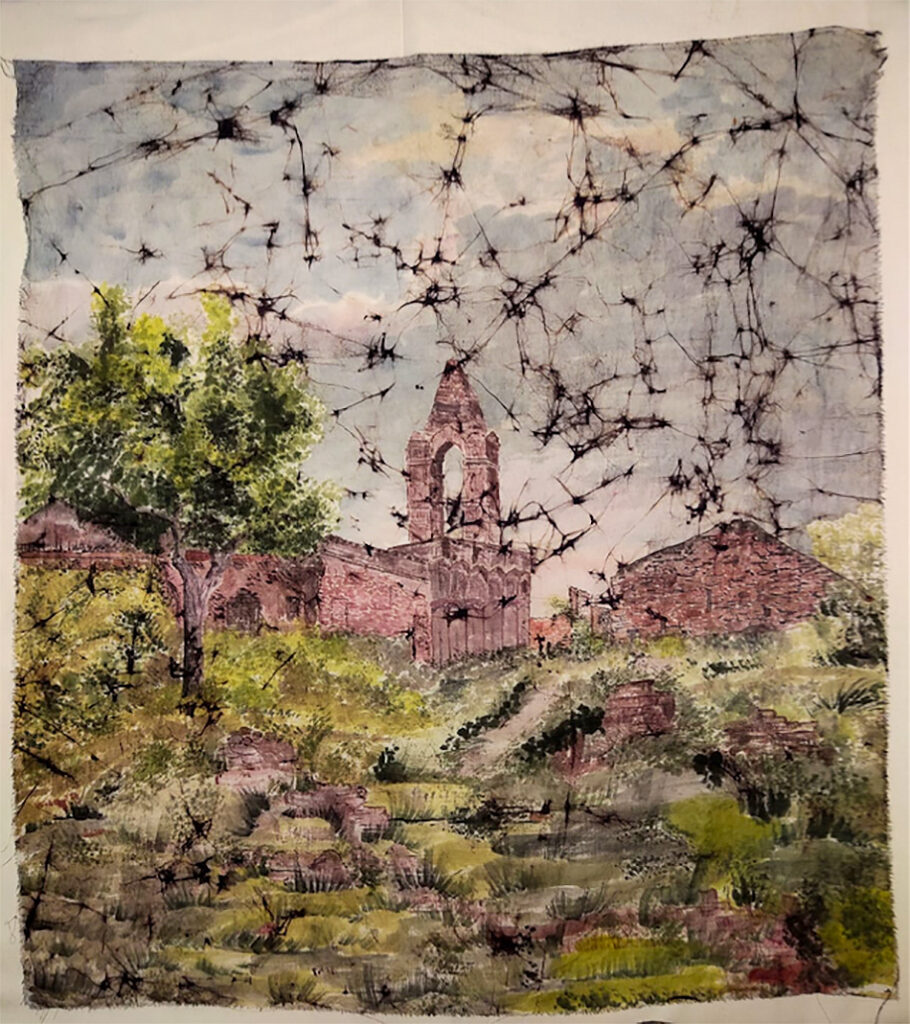

- Sunflower by Anwarbhai Khatri

The future remains unknown. Shakil bhai is not sure if he should print more fabric: “I do not have a retail market as I supply to wholesale markets. I already have enough stock but I do not know if the retailers would want to buy my stock.” Anwarbhai Khatri, from Bhujpur, also a batik artisan, has recently created many innovations of beautiful sunflower prints. He too has a huge amount of unsold batik fabric and many orders cancelled, explaining: “I do not know what will sell after the lockdown opens. I am worried as I do not have enough savings.” Deviben, an applique artisan from Vadaj, Ahmedabad, has realised the importance of savings: “But how to save, when I don’t earn enough?” she asks adding that she doesn’t have any raw materials to make anything new.

- Covid painting detail Warli artits Ramesh

- Mud cake by Ramesh and his children

- Ramesh Hengadi

Warli artisan Ramesh Hengadi, from Bapugav Maharashtra, is using rice paste to make new paintings; “I do not have any more poster colours, so I thought to use rice paste, which was traditionally used to paint the house walls.” This may not last for long, but it is an immediate solution. He is thinking of using bamboo if his paintbrushes become unusable but he is concerned if any tourists visit his village to buy paintings. From Bhujodi, Dayabhai Atmaram Kudecha, a weaver and graduate of the SKV Business and Management for Artisans course feels fewer tourists would now visit Kutch. He has been reading about financial depression: “I am thinking of minimizing the risk by making a production that draws less on resources—limited production. I am thinking of luxury and sustainable products.” Like Sitaben, he is focusing on using the unused raw materials he currently has in his home.

Buyers and consumers have to reflect that in order to really help the artisans, they understand and respect both the skilled work and creativity of the artisans. There should be an openness for paying fair wages; giving credit to the artisans and purchasing directly from the real maker.

The way forward—post-pandemic—is to elevate the value of craft. Artisans don’t need just more work, they need to be properly compensated by wages that reflect their level of skill and experience and ultimately pays better. Let’s call Sitaben’s garlands a Garland of Hope and Wisdom, that will fetch her a dignified living wage. And let’s hope that other artisans find their garlands soon!

- Dayabhai Atmaram Kudecha

- Stole by Dayabhai Atmaram Kudecha

Organisations

List of craftpersons featured in the article:

Garland by Sitaben Chavda

Sitaben Chavda

Stole by Shanti Devi Bora

Shanti Devi Bora

Late Jivya Soma Mashe

Sari by Basirbhai Khatri

Basirbhai Khatri

Batik by Shakil Ahmed Khatri

Shakil Ahmed Khatri

Kaftan by Bharatbhai Jepar

Bharatbhai Jepar

Bandhani by Adilbhai Khatri

Adilbhai Khatri

Sari by Junedbhai Husen Khatri

Junedbhai Husen Khatri

Amitbhai, Maniram’s son

Vaishaliben making mask

Sunflower by Anwarbhai Khatri

Anwarbhai Khatri

Covid painting by Warli artist Ramesh

Ramesh Hengadi

Mud cake by Ramesh and his children

Stole by Dayabhai Atmaram Kudecha

Dayabhai Atmaram Kudecha

Author

Based in Ahmedabad, LOkesh Ghai is a textile artist, researcher and academician working with traditional craft practice. In 2011, his textile art responding to the folk story of Frozen Charlotte was featured at the V&A Museum of Childhood, London. As a designer and associate curator he presented India Street exhibition in Scotland; the show was a runner up for the most sustainable design practice award in the Edinburgh International Art festival 2014. This was followed by India Street part-two showcased in Tramway, Glasgow; and at Conflictorium museum, Ahmedabad in 2017. He has been visiting lecturer at numerous institutions including the National Institute of Fashion Technology, Gandhinagar, Royal College of Art, London and Somaiya Kala Vidya, Kutch, India’s premier design institute for traditional craft communities. In January 2020 NID published a book by LOkesh on the Cotton Mill narratives: Baku’s Rag book: Untold story of the discarded fabric. Recently, he taught a course on Compassion at the institute. Currently, he is working on the Katab project.

Based in Ahmedabad, LOkesh Ghai is a textile artist, researcher and academician working with traditional craft practice. In 2011, his textile art responding to the folk story of Frozen Charlotte was featured at the V&A Museum of Childhood, London. As a designer and associate curator he presented India Street exhibition in Scotland; the show was a runner up for the most sustainable design practice award in the Edinburgh International Art festival 2014. This was followed by India Street part-two showcased in Tramway, Glasgow; and at Conflictorium museum, Ahmedabad in 2017. He has been visiting lecturer at numerous institutions including the National Institute of Fashion Technology, Gandhinagar, Royal College of Art, London and Somaiya Kala Vidya, Kutch, India’s premier design institute for traditional craft communities. In January 2020 NID published a book by LOkesh on the Cotton Mill narratives: Baku’s Rag book: Untold story of the discarded fabric. Recently, he taught a course on Compassion at the institute. Currently, he is working on the Katab project.

Comments

Very nicely written and a beautiful perspective put forward in a humble way.

It is convenient to adapt to trending opinions about crafts, but an indepth analysis and on field data is important to even have a constructive discussion, which this article very well highlights.

Keep writing and sharing your insights.

Excellent work in supporting Kraft industry and promoting real geniuses behind the scene. Keep it up and good luck.

Thank you for writing this article, I really enjoyed reading it, especially the quotes by the artisans themselves, which is something one doesn’t usually get to hear.

I think the point you make about not patronizingly trying to “help” artisans by giving them more work but instead listening to them and ensuring a fair wage, is such an important point to make. It should be something that people understand naturally but of course, class blinds everyone.

Personally I don’t have too much hope from the current system so I’m imagining that this will have to be shouted from the rooftops repeatedly before anyone really hears it… But things are slowly changing in other parts of the world too, for the better, and hopefully they’ll change here too.

Congratulations on your article. I have been obviously very concerned that living here in London it is hard to know how rural and urban crsftspeople are coping with the effects of Covid-19. especially in Ahmedabad where the cases are high..

Post pandemic challenges around how families can continue to work and thrive needs to be so much better understood by policy makers and consumers of crafts. alike.

Hearing the views from crafts people directly is vital. I hope you will write more of these pieces of your on the ground research during the coming months.

Great article LOkesh, it would be good to hear how these craftspeople go as time unfolds. A follow up would be really interesting. Many of us here in Australia are experiencing similar/but different problems re supplies, drying up of income etc to what you have outlined.. common themes abound. Warmest wishes Vicki

I was reminded of every person I met in Kutch. And the patronizing student was spot on. Perhaps there should be a course on ethics of interaction and collaboration with traditional craftspeople. I would definitely want to attend. It’s so easy for urbanites to see a crafts person as a source of cheap labor. Even if we get over that terrible idea, there must be so many things we unconsciously do that can be harmful the craftsperson and the craft as a whole. This is a somewhat unique problem for developing countries.

I also loved your writing by the way! You go way beyond the surface to really explore the mind of the artisan.

Well u covered things very well , most of them from Gujarat though.. I just thought how every region have their folk songs likewise they might have their own way of artistic patterns.. u covered most of the things well , I don’t agree that PhD student giving justification about ppl on top … at ground level exploitation is very deep .. some one is slavering and other is making loads of money just for the labels …. Their should be some something which eliminate this gap .. like profit sharing .. over all u made me think how ppl value s the labels over hand behind the beautiful art !!!