Collage of images from Hassan Laarousi’s Instagram, showing stages of guembri making. @guembrihassan

In the fifth instalment of #africamade_n_played, Gary Warner writes how Western ears are deaf to the essence of this West African instrument.

First, a little on names because the instrument I’m going to write about here is referred to by many—sintir, sintar, sentir, gimbri, guembri, guinbri, goumbri, hejhouj, hajhouje, hahjuj—perhaps due to transliteration from Arabic to European languages of terms with earlier origins in African oral cultures neither Arabic nor European. Here I will use the term guembri because that’s the name used by the craftsman Hassan Laarousi from Essaouira, a centre of Gnawa culture. Hassan makes guembris, plays gnaoua music and maintains a visually rich Instagram account (@guembrihassan) where he documents his prolific hand-making of exquisite guembri instruments.

Traditionally nourished by incense ceremonially wafted over its body, the guembri is a musical instrument central to gnaoua music of the Gnawa, an ethnic population of northwest Africa with origins in centuries-old intra-African south-to-north slave trading (which persisted into the twentieth century). The powerful pre-Arab nomadic clans of the region, the Amazigh, brought slaves north from west Africa and the guembri is a variant development on stringed instrument forms of the Sahel cultures of the enslaved. Over time, those inherited musical forms were transformed by the materials and new cultural contexts into which those forcibly displaced people were carried. The most influential was the eighth century CE arrival of Islam to North Africa, and today’s gnaoua music predominantly conflates the swirling trance of Islamic Sufism with pre-Islamic West African spiritual and animist ritual traditions. But other influences include Sephardic Jewish refugees from fifteenth-century Spain who settled in Morocco, and there is a resultant “Jewish songbook” within the Gnawa repertoire today.

Guembri player in Rabat, Morocco. 2011 photo: Lars Curf

The guembri is an oblong or long rectangular wood-bodied fretless three-stringed instrument, held like a guitar and plucked and struck with fingers and thumb. The soundbox body is hollowed from a halved tree trunk or limb, then polished and perhaps decorated with inlay on the verso before being tightly covered with stretched camel skin on the playing side which might be decoratively enhanced with henna. A soundhole is cut into the taut skin at the lower end. A thick wooden dowel inserts under the skin to the soundhole and extends out from the body to form the neck. Three long goat-gut strings are tied on the dowel near the soundhole, tensioned over a carved timber bridge and traditionally tied with leather or cloth thongs at points along the neck. Two outside strings are fixed at the top of the neck; the middle string is tied through a hole about halfway along. Today, most guembris are fitted with metal tuning pegs, but a leather thong will often tie down the longer strings.

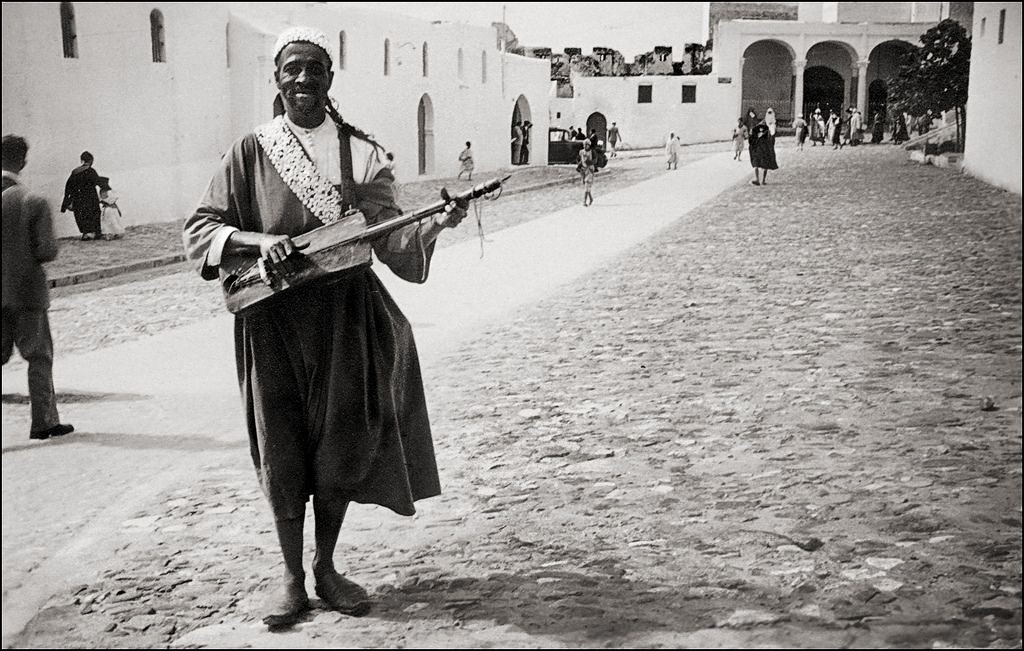

Guembri player on the streets of Tangier, c.1935.

While players tune their instruments to suit their preference, the tonal relationship between the strings is usually about an octave between longest and shortest, and about a fifth between longer and longest. The gut strings produce clear rounded bass notes by plucking with thumb and index finger. But another crucial aspect of the guembri sound style is percussive tapping on the soundbox’s camel hide covering for emphatic drum-like sonics.

The third acoustic component of the guembri sound is a jingly rattling effected by the sersal, a thin, flexible metal plate fitted into a hole at the top of the neck. Often shaped like a stylised flame, the plate is encircled by rings or tiny bells that quiver in vibrational sympathy with the player’s movements. The preference for this insect-like buzz is surely descended from the West African sonic world of music—mbira and balafon, for example—lost to those original displaced slaves.

Guembri player of the Gnawa Khamlia village, Moroccan Sahara. 2019

In 1959, expatriate American author Paul Bowles was awarded a Rockefeller Foundation grant to make field and studio recordings of traditional and popular music in Morocco where he lived from 1947 until his death in 1999. Over August to September of that year, he travelled widely and recorded over 60 hours of material. But he had his own “Western ear” ideas about some of the music he encountered. In one instance he asked a respected Gnawa guembri player to remove the sersal from his instrument because Bowles heard the buzz as an annoyance rather than as an entwined aspect of a deep sonic tradition. Today, many guembri players performing for Western audiences don’t attach the sersal either, perhaps believing “Western ears” find it unpleasant or distracting.

In its traditional ritual setting of the dusk-to-dawn healing ritual known as lila or derdeba, the guembri player is a respected maalem, a master singer who is accompanied by his troupe of musician-singers playing distinctive doubled metal castanets known as qraqab (or krakeb, garagab, etc.) and hand-clapping. In ongoing repetitive call and response structure, the maalem sings phrases and chants that are repeated in chorus by the others who all the while use their handheld qraqab to sound hypnotic clattering rhythms reminiscent of galloping horses or, when slower, perhaps the gait of a pack-laden camel.

Revered Maalem Mahmoud Guinia (1951-2015) playing at home for guests, Essaouira, Morocco. 2010. photo: Mike Rivard

The lila has a ritual structure wherein seven different spiritual entities—the mluk—each associated with one of seven rhythm and melody patterns, seven incenses and seven colours, are sequentially invoked in the presence of the moqqaddema, an attending woman clairvoyant who partners with the maalem. The troupe wear elaborate, decorative costumes of changing colour combinations through the night depending on the spirit presence. People attending the lila, which takes place in a domestic setting, become possessed by the supernatural visitors and enter ecstatic dance trance states as a form of healing. The musicians play continuously through the night, taking participants on a transcendent cosmogenic journey that will always and only return to the mundane world with the rising of the sun.

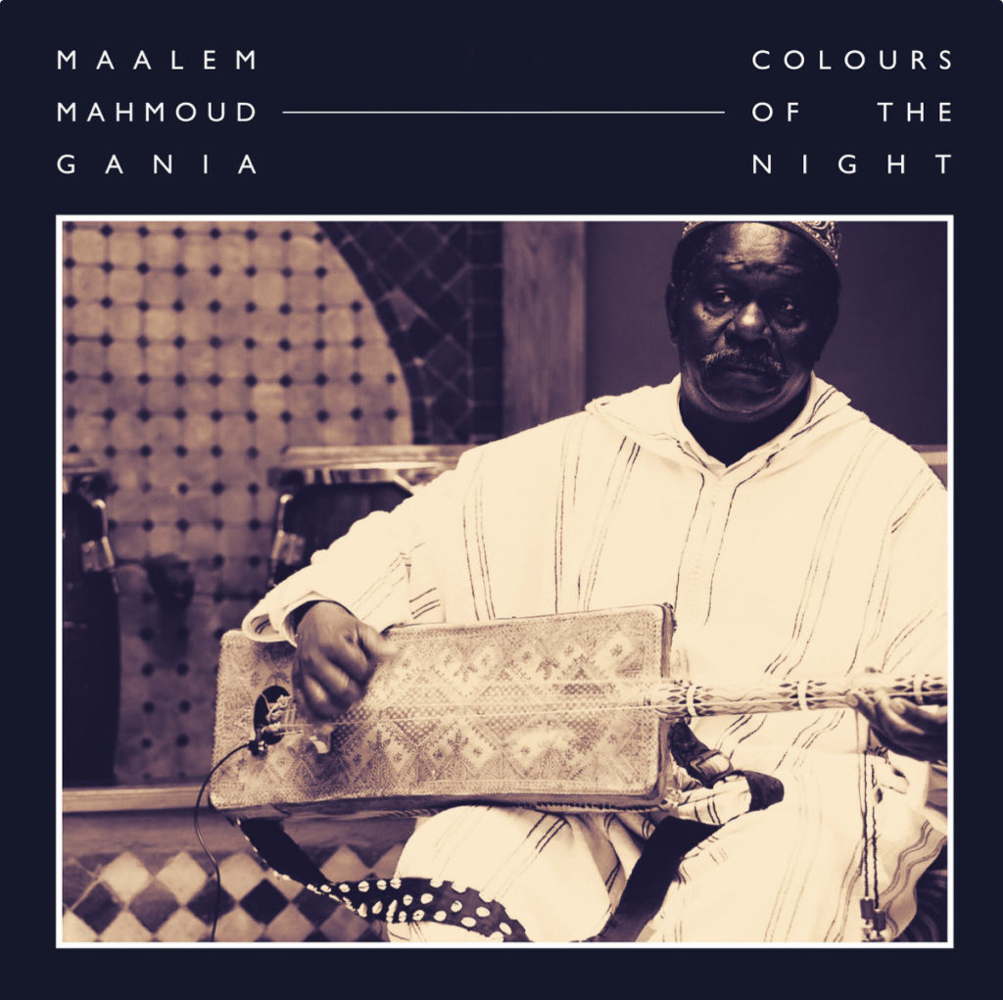

Album cover – Maalem Mahmoud Gania (Guinia) – Colors of the Night, Hive Mind records 2017.

For displaced people everywhere and throughout time, music and song from “home” provide an embodied form of connection with what, where and who has been lost. The enslaved peoples who “became” today’s Gnawa would have sung songs in their original languages, at the same time needing to learn and speak the language of their captors. As generations moved through time, the meaning of those original words became blurred and lost, leaving only sound and rhythm in place of meaning and connection. Those remnant songs, comprised of no longer comprehensible utterances, have become a contemporary Gnawa tradition, the Bambara song repertoire.

Woods used in the construction of a guembri can include mahogany, walnut, poplar or iroko for the body, cedar or iroko for the neck dowel, and contrasting decorative inlays of pale lemon tree and dark mahogany. The iroko tree (Milicia excelsa) is important in many West African sacred traditions. Associated with fertility and birth, iroko trees are revered, given offerings and its timber used for making ceremonial drums. Perhaps in the material fabric of this ritual musical instrument, the guembri, is another tracery of cultural connection stretching across the centuries, evidence of an ancient heritage of displacement and longing for home.

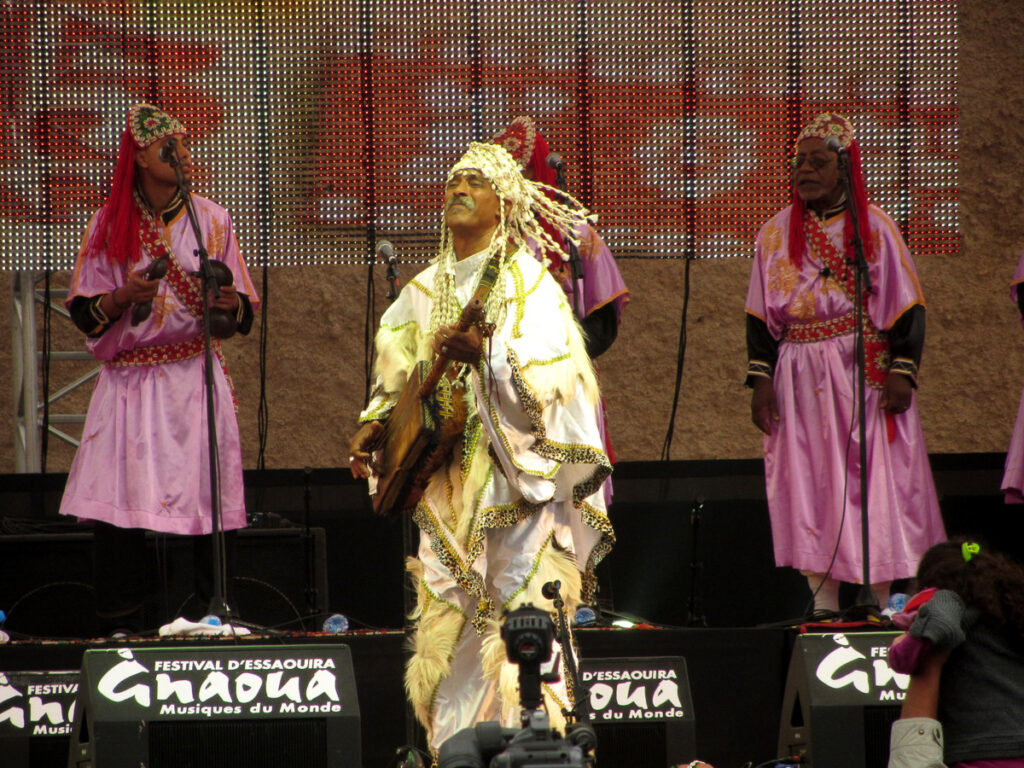

Performers on stage at Gnaoua World Music Festival, Essaouira, Morocco. 2012. photo: Adam Taylor

Links

Hassan Laarousi‘s videos demonstrating his various handmade guembri

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCB68SeyaaiXunfGXV5XKfiw/videos

Hassan Laarousi in his workshop, playing guembri at work bench

1959 Recording of Si Mohammed Bel Hassan l’Sudani, by Paul Bowles. The sersal’s rattle can be distinctly heard in this recording.

1969 French TV footage of a gnaoua lila in progress

New York based gnaoua group Innov Gnawa perform Toura Toura – a Bambara song

Innov Gnawa performing from the Gnawa Jewish songbook, in Baltimore

Best of the Gnaoua Festival at the Bataclan, Paris 2017

Maalem Hamid El Kasri performing for Moroccan TV

Maalem Mahmoud Guinia live performance at the Boiler Room Marrakech, 2014

An interesting collection of vintage Moroccan guembri cassette recordings.

Author

Gary Warner is an artist and art worker with a studio in Darlinghurst, Sydney and an off-grid bush retreat 50km north-west of there. In 1997 he started CDP Media, a cultural production company that has developed and delivered a wide variety of museum exhibition projects in collaboration with FRD and other designers, architects, artists and curators. His personal art practice spans various media including sound, video, drawing, installation and performance in contexts including writing, curating, collaboration, design, workshops and exhibitions. In 2016 he curated FIELDWORK: artist encounters at the Sydney College of the Arts and was commissioned by FRD to create a permanent multi-screen video installation for a new ceramics gallery at the Asian Civilisations Museum, Singapore. For more information, see garywarner.net, fieldwork.show and cdpmedia.com.au

Gary Warner is an artist and art worker with a studio in Darlinghurst, Sydney and an off-grid bush retreat 50km north-west of there. In 1997 he started CDP Media, a cultural production company that has developed and delivered a wide variety of museum exhibition projects in collaboration with FRD and other designers, architects, artists and curators. His personal art practice spans various media including sound, video, drawing, installation and performance in contexts including writing, curating, collaboration, design, workshops and exhibitions. In 2016 he curated FIELDWORK: artist encounters at the Sydney College of the Arts and was commissioned by FRD to create a permanent multi-screen video installation for a new ceramics gallery at the Asian Civilisations Museum, Singapore. For more information, see garywarner.net, fieldwork.show and cdpmedia.com.au