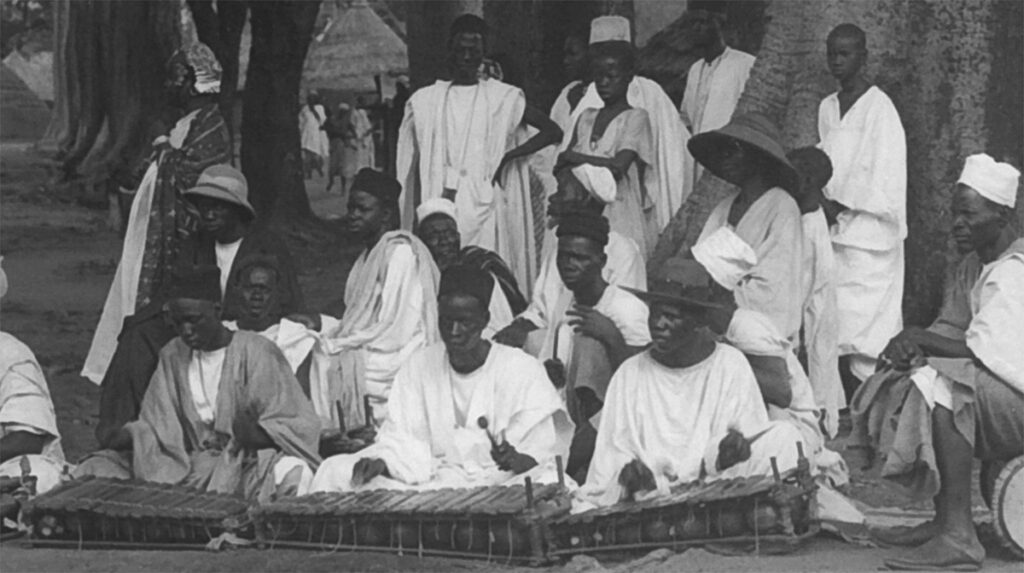

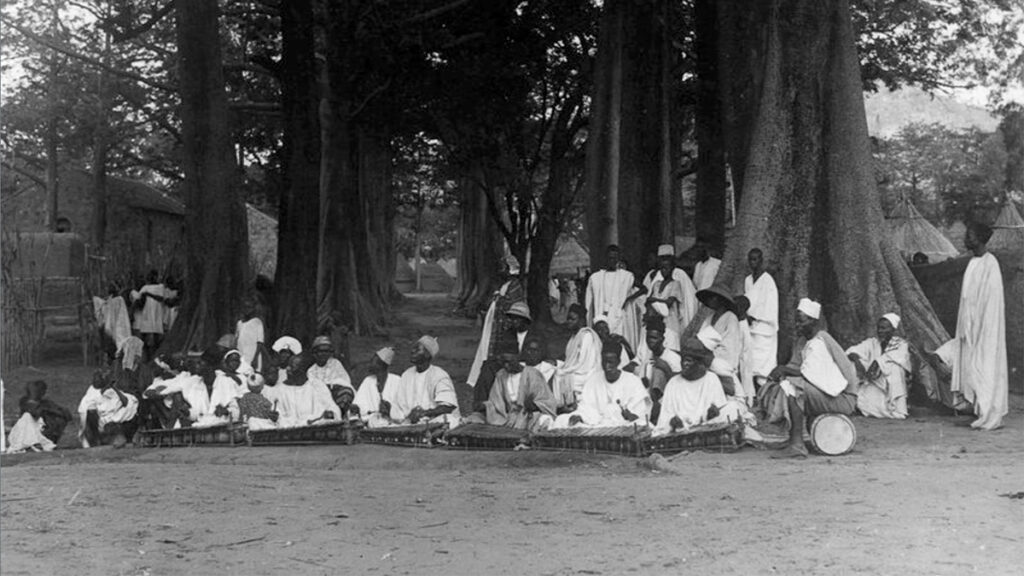

- Balafon orchestra, Kita, Mali 1931. photo: Marcel Griaule. Archives du Musée du Quai Branly – Jacques Chirac.

- Balafon orchestra, Kita, Mali 1931. photo: Marcel Griaule. Archives du Musée du Quai Branly – Jacques Chirac.

In the fourth instalment of #africamade_n_played, Gary Warner writes about an enchanting West African instrument that gives voice to trees.

The sound produced by just one skilled balafon player is a kind of beguiling sonic illusion. It’s hard to believe the rich, complex acoustic experience is being generated by only one instrument and player. In the tradition of the Sambla speaking people, one balafon is played by three players at once with similarly hard-to-believe synchronous dexterity. More on this later.

The word “balafon”, shared in English and French, is derived from a Mande word or words meaning something like “wood-tongue-talk”. With over 70 languages and dialects in the Mande language family, names for the instrument, its forms, uses and playing styles, vary with locale—balanyi, bala, balo, ncegele are a few. The word “xylophone”, derived from Latin and coined for English in 1866, means something similar: “wood-sound” or “wood-speak”. So, the balafon is an African xylophonic instrument of particular form originating, it is said, circa twelfth century CE in the region of West Africa centred around today’s Burkina Faso and including neighbouring areas of Mali, Guinea, Ghana and Cote d’Ivoire. Centuries of local migration from within this region has carried the instrument form further around the Sahel.

- Impromptu balafon and dance performance, Sikasso, Mali 2008. photo: Rebecca Fenton

- Balafon players, Bandiagara plateau,Mali c16CE. Collections of Musée du Quai Branly – Jacques Chirac. photo: Martin Senflteben 2011

- Detail of a bobo balafon showing membrane patches, Upper Volta, Côte d’Ivoire 1978. photo: B. Mondet. Archives du Musée du Quai Branly – Jacques Chirac.

There are various epic origin narratives for the balafon. Still, most include its gifting from supernatural beings to a significant, named ancestor, and it remains of central cultural significance to peoples of West Africa today. In 2008 an eight-hundred years old sacred balafon instrument preserved in northern Guinea, known as the Sosso- Bala, was inscribed on UNESCO’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. In 2012 the cultural practices and expressions linked to the balafon of the Sénoufo communities of Mali, Burkina Faso and Côte d’Ivoire received the same acknowledgement.

- Balafon ensemble performing on the move in Ferké, Côte d’Ivoire 2017. Wikimedia Commons.

- Makan Dembélé performing on a bwaba balafon built at the BaraGnouma workshop, Bobo-Dioulasso, Burkina-Faso. baragnouma.com Still-frame from BaraGnouma video – see Links

- Makan Dembélé performing on a typical balafon built at the BaraGnouma workshop, Bobo-Dioulasso, Burkina-Faso. baragnouma.com Still-frame from BaraGnouma.com video – see Links.

The distinctive principal form of a balafon comprises a hide-strung bamboo or timber frame supporting a single linear array of tuned hardwood keys with calabash gourds suspended below. It is these suspended gourd resonators that set the balafon apart from other African xylophonic instrument forms. Depending on local preference and custom, balafons might be played on the ground (most usual), set on a stand, or carried on the mobile body of the player using a heavy strap spanning both shoulders.

There are also locally specific variations of form. While the frame of a Sambla balafon is slightly inclined to accommodate the small-to-large calabash array, the frame of a Bwamba balafon is acutely curved. Each requires a different playing style. Other locally variant preferences include the drying treatment of the timber, the size, number and pitch of keys, and the exact type and shape of the gourds cultivated for the instrument and whether they are colour-treated or not.

Each dried and hollowed gourd is selected and carefully shaped to act as a resonating chamber for its partnered wooden key. The higher-pitched notes of the shorter keys require smaller rounder gourds, while the longer keys of the low notes can demand quite large obloid examples. Some makers believe this tuning is best done at night after the noisy activities of daily life have subsided into the relative quiet of the evening.

One or two holes are cut into the wall of each gourd and covered with a light membrane to produce a fluttering buzz—a mirliton effect, like the sound of a kazoo. This sonic nuance adds vibrancy to each sounded note and players sometimes wear bracelets to add extra rhythmic rattle and buzz to their sound-style. Traditionally the little buzzing membrane was made with the silken mesh of spider egg sacs or the transparent wings of microbats, fixed with sticky sap. Today, swatches of the ubiquitous plastic shopping bag, or cigarette papers, make-do the function. Similarly, tradition demanded the skin of a particular antelope be used to bind the frame and keys. Today, that species is in decline due to habitat loss, so goatskin string or manufactured rope is substituted.

However, the wood used for balafon keys requires particular properties of sonic clarity, strength and insect resistance. The preferred timber is the heartwood of Pterocarpus erinaceus, a valuable hardwood species also in decline due to over-harvesting for other uses and export. For the balafon, the tree is best found in the wild already senescent (aged and dying). It is left in-situ for a few years to naturally dry before being harvested. The trunk is split and gradually broken down into rough-sawn key blanks that will be dried further using either the sun or a low-temperature mudbrick kiln. Sometimes the wood is smoked and blackened. Each blank is then carefully planed, filed and sanded into shape with the maker periodically striking the developing key to assess and hone its pitch.

- Sa Adama Diabaté (soloist), Sa Mamdou Traoré and Karim Traoré playing their Sambla language balafon playing style at the BaraGnouma workshop, Bobo-Dioulasso, Burkina-Faso. baragnouma.com Still-frame from BaraGnouma.com video – see Links.

- Diabaté Pantio Moussa and friends performing “Orodara Sidiki”, Bobo-Dioulasso, Burkina-Faso 2012. Still-frame from BaraGnouma.com video – see Links

Larger keyed, lower-pitched balafons might have only fifteen keys. A typical balafon will have between seventeen and twenty-two keys spanning a little over four octaves in a pentatonic or diatonic tuning. But balafons are not pianos or guitars: each balafon, like each human, has its own voice, its unique sound spirit.

At the core of traditional balafon playing is a dynamic pairing between an embodied understanding of scores of well-known songs whose rhythmic, harmonic and melodic structures are understood by the community, and each players ability to riff on these patterns, keeping them freshly animated for the listening audience with flourishes of inventive improvisation. Playing solo requires expression of both registers at once. Ensembles of more than one player—either on a single or multiple balafons—allow for the definition of registers according to the skill, age, experience or social status of players.

For example, each of the trio of Sambla men, playing their shared balafon together, has a distinct musical role. Two players on one side are more experienced, the third sitting opposite is a younger novice, developing his skills (by tradition, balafon players are male). He must hold the underlying rhythmic pattern on the instrument’s central tonal range. A player opposite supports him on the lower notes (the bass line, perhaps) but also adds improvisational surprises.

Both are essentially accompanists to the most senior or experienced player. He is the “soloist” who performs a musical ventriloquy on the higher notes. This is a form of speech surrogacy wherein the rapidly played notes imitate words and phrases of the communities tonal language form. Listeners can understand the player’s musical pronouncements, which might be the recitation of proverbs, requests for donations, confirmations of actions, or commentary and gossip. The balafon player can amply praise or pointedly criticise without offending: it is the balafon speaking, not the player. This construct provides a socially acceptable outlet for otherwise tricky commentary.

- West African born international musician Aly Keita performing on balafon, Jazz Club Unterfahrt, Munich, Germany.

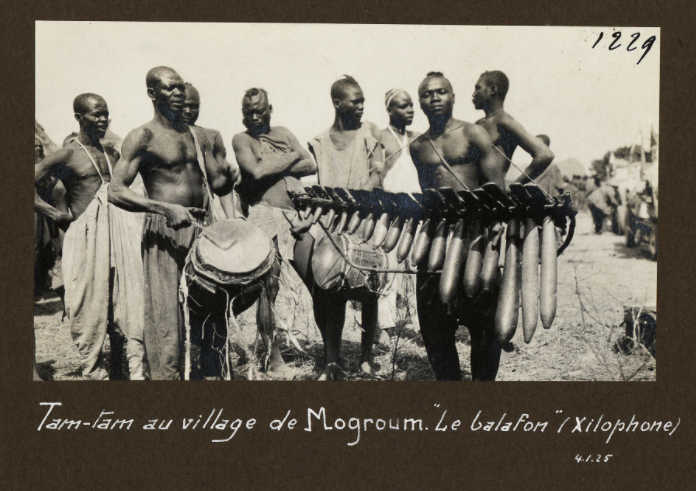

- The balafon form radiated out of west Africa through migration. Chad, 1925. Mission Citroën Centre-Afrique (1924 – 1925). Archives du Musée du Quai Branly – Jacques Chirac.

- The balafon form radiated out of west Africa through migration. Congo 1946. photo: André Didier. Archives du Musée du Quai Branly – Jacques Chirac.

The performance of balafon music spans many social and cultural contexts including farm labour, joyful entertainment, sacred ritual and prayer, the child’s naming ceremony, initiatory life stages, and weddings and funerals. Some balafon musical traditions are instrumental only (but for the words “spoken” by the balafon) while others include singing by players and accompanying song by women of the community.

Contributing to the sustenance of traditions, beliefs, customary law, and ethics governing the day-to-day life of the individual and society, the sound and repertoire of the balafon is central to cultural identity for a spectrum of west African language groups and communities. For musically curious listeners outside its geocultural origins, the sound of balafon is impressive, mesmerising, uplifting and remarkable.

____________________________________________________________________________________

LINKS

BaraGnouma is a Mandingo-inspired traditional West African music-making workshop located in Bobo-Dioulasso, Burkina Faso. Over twenty artisans build instruments there, most of them griot musicians.

Makan Dembélé demonstrates a typical BaraGnouma balafon.

Makan Dembélé demonstrates a bwaba balafon built at BaraGnouma workshop.

Diabaté Pantio Moussa and friends performing “Orodara Sidiki”, Bobo-Dioulasso, Burkina-Faso 2012. Stillframe from a BaraGnouma video youtube.com/watch?v=cXm_ms7X43s

Sambla balafon traditionally played by 3 people at BaraGnouma workshop.

Baragnouma workshop making of a balafon.

Exploring the Malian Balafon with Balla Kouyaté

Phone camera video of young men synchronised dancing to sounds of balafon ensemble. 2020

UNESCO video on the eight-hundred years old Sosso-Bala.

Construction of a balafon – French TV doco, commentary.

PhD research resources site of Canadian musicologist, balafon player and researcher Todd Martin.

Author

Gary Warner is an artist and art worker with a studio in Darlinghurst, Sydney and an off-grid bush retreat 50km north-west of there. In 1997 he started CDP Media, a cultural production company that has developed and delivered a wide variety of museum exhibition projects in collaboration with FRD and other designers, architects, artists and curators. His personal art practice spans various media including sound, video, drawing, installation and performance in contexts including writing, curating, collaboration, design, workshops and exhibitions. In 2016 he curated FIELDWORK: artist encounters at the Sydney College of the Arts and was commissioned by FRD to create a permanent multi-screen video installation for a new ceramics gallery at the Asian Civilisations Museum, Singapore. For more information, see garywarner.net, fieldwork.show and cdpmedia.com.au

Gary Warner is an artist and art worker with a studio in Darlinghurst, Sydney and an off-grid bush retreat 50km north-west of there. In 1997 he started CDP Media, a cultural production company that has developed and delivered a wide variety of museum exhibition projects in collaboration with FRD and other designers, architects, artists and curators. His personal art practice spans various media including sound, video, drawing, installation and performance in contexts including writing, curating, collaboration, design, workshops and exhibitions. In 2016 he curated FIELDWORK: artist encounters at the Sydney College of the Arts and was commissioned by FRD to create a permanent multi-screen video installation for a new ceramics gallery at the Asian Civilisations Museum, Singapore. For more information, see garywarner.net, fieldwork.show and cdpmedia.com.au

Comments

Le balafon est beaucoup plus ancien…Du Mozambique ANGOLA Zone ÉQUATORIALE il a suivi les hommes lors des grandes migrations humaines…il se retrouve jusqu’en Thaïlande INDONÉSIE phillipines .En Afrique les zones balafoniques vont de l Afrique du sud australe équatoriale centrale longeant le nord du Nigéria du GHANA s’étendant dans L afrique de louest….il y eut plusieurs milliers d’années avant d’atteindre sa technique de fabrication actuelle….Le balafon est le propre du génie de l’homme….Pythagore eu a découvrir la gamme pentatonique de certains balafons en Égypte…Le balafon et ses gammes et résonances expriment plus qu’on ne croit des calculs et figures soniques qui peuvent être transformés en langage mathématique et informatique…Le balafon existe depuis avant l’ère pharaonique.