Pamela See writes about Queensland artist Vanghoua Anthony Vue, whose work offers an insight into the epic cultural journey of the Hmong.

The 21st of March has been set aside by the United Nations as an International Day for Elimination of Racial Discrimination. In Australia, this calendar observance is known as Harmony Day. It is a celebration of our diversity, with an emphasis on the successful settlement of migrants. Museum of Brisbane (MoB) presents the interesting case of the Australian Hmong community, through the artist residency Ua li ua tau – Making do by Vanghoua Anthony Vue. Visitors are invited to watch, as he develops a display for an adjoining corridor.

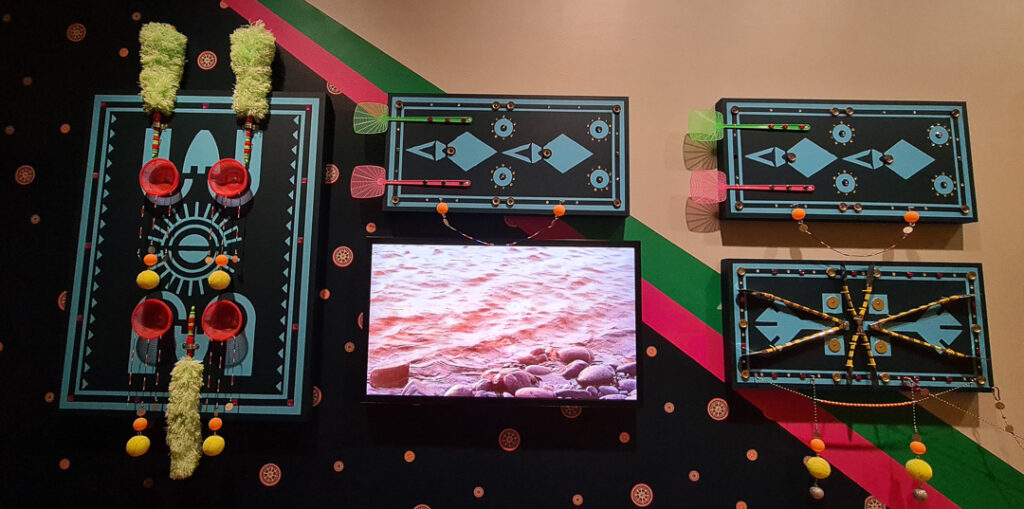

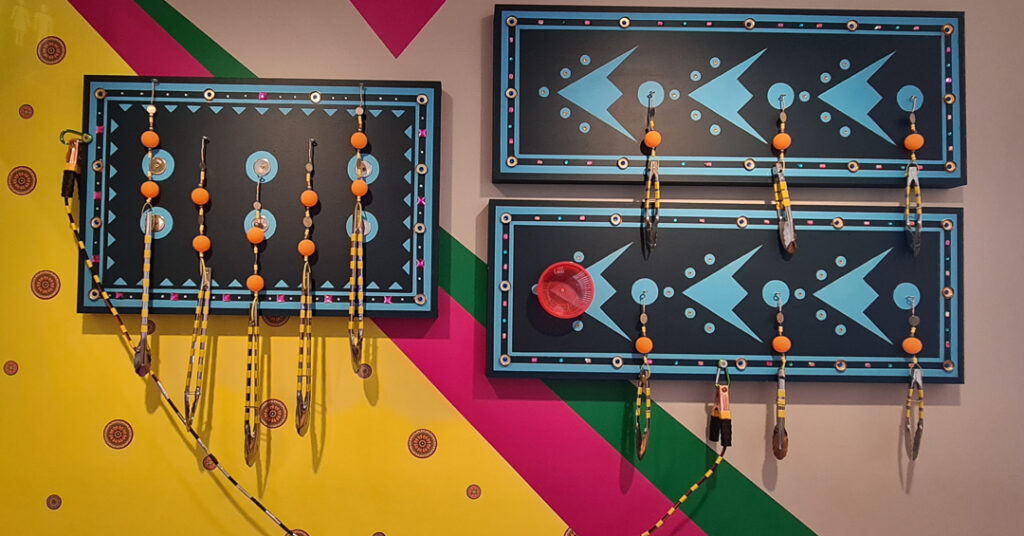

For all intents and purposes, the evolving exhibition will engage people from a plethora of backgrounds. The youngest viewers are likely to delight in the vibrant patterns Anthony has created through painting and assemblage. The latter incorporates mass-produced items, many of which have domestic applications, from table tennis balls to paint scrapers. Art aficionados may read this as a nod to the Arte Povera of the late 1960s and early 1970s. Some of the complex compositions are literally tied together with strings of synthetic beads, interspersed by fishing sinkers. This may appeal to craftspeople who worked in Australia in the 1990s, when “poor craft” implied the incorporation of everyday objects. The substrates are boards painted with totemic-esk abstract symbols. They could be appreciated in light of the recent coining of “shield painting” as a distinct genre of contemporary art by Eric Bridgemen.

The walls have also been painted with patterns and embellished with custom-designed stickers. They signal to the viewer that the artworks are to be considered components of a larger installation. LCD screens play interviews with members of the Australian Hmong community and documentary footage from the Mekong, Logan and Brisbane rivers. The latter juxtaposition interjects a natural element into a constructed landscape, which has been primarily crafted using manufactured objects. Unlike the documentation of rivers by Bonita Ely, these sequences record single vantage points. As a point of difference from the powerful Wunderkammers assembled by Tony Albert, most of the products Anthony has presented are, in and of themselves, ordinary. Most visitors are likely to be satisfied with some aspects of this eclectic artwork. However, contentment in the familiar ultimately leads to containment within cultural constructs.

To fully appreciate this artwork, viewers may need to try on a new lens. Aside from the sight of his work serving to entertain, Anthony speaks on behalf of a community that has been marginalised for its steadfast devotion to harmony. Integral to the identity of the Hmong is animism, which in their interpretation entails spirits inhabiting all organic and inorganic matter. Physical and spiritual imbalance is considered a cause of illness. A subgroup of the Miao, who have an autonomous region in China, his people are recognisable by the intricate iconography that embellishes their textiles. The floral symbols on their garments serve as protection, both metaphysically shielding themselves and materially documenting their culture. Although Anthony identifies as a “White Hmong”, by virtue of his creed traditionally wearing white embroidered garments, the indigo motifs of Queensland flora in his painting reference the distinctive batik textiles of the “Black Hmong”.

The literal translation of Hmong is “free man”. The refusal of this indigenous community in China to assimilate has led to periods of conflict and statelessness. Anthony’s ancestors were amongst the Hmong who had settled in Laos during the nineteenth century. A genocide in the 1970s, born of a communist reaction to the community assisting the Central Intelligence of America (CIA), forced his parents to flee across the Mekong River into Thailand. This geographic location features in one of Anthony’s videos. Anthony, his parents and five siblings, were amongst the population of 603 Hmong in Queensland in 1996. Intermarrying has, until recently, been strongly discouraged. The maintenance of some culturally specific practices requires the presence of a group. Rituals to return the spirits to a sick body or guide the deceased to the afterlife traditionally involve animal sacrifice. The subsequent carcasses are collectively consumed.

It is notable that whilst some of Anthony’s constructions bear resemblance to animal parts, such as horns, others engage synthetic materials that resemble them, like feather dusters. In the past, Anthony has taken care to select only items which the subjects of his portraits have physically touched. This autobiographical artwork uses products that are representational of places of residence. Although not expressly articulated through this installation, there is a Hmong belief that the soul of a person travels back to their birthplace at death. These spirits are in search of the placentas they left behind. His siblings were born in Thailand, in the Ban Vinai Refugee Camp, where his parents met during a sojourn that exceeded a decade in length.

Amongst the localities represented is Anthony’s present home of Logan City. He has reimagined its floral emblem, by applying cross sections of banksia flowers to boards. The abstract markings are reminiscent of a sports field, of which the municipality is abundant. This repetition of circular forms extends beyond the picture planes, through the attachment of large metal sieves to the bottoms of the compositions. These are balanced with badminton rackets, protruding from the tops. Their handles and stems are painted with red, yellow and black stripes, a combination typical of “Red Hmong” attire. Whilst engaging in a level of assimilation, through participating in pastimes like sport, many migrants also enrich their adopted communities by maintaining their cuisine and crafts.

Anthony will be Artist in Residence in MoB on Fridays and Saturdays until 22 April 2023, and his work will remain on display until June. Visitors to South-East Queensland and its residents are encouraged to experience this testament to the resilience and ingenuity of migrants. These attributes may be broadly applied to settlers from many nations. However, the determination to survive is particularly pronounced in the example of the Hmong. Anthony’s are a people who have preserved their culture despite millennia of persecution. Although this was, arguably, achieved through adaptation, harmony has been maintained as a defining principle.

Follow @vanghoua_anthonyvue

Further Reading

Buttrose, E. (2022). Vanghua Anthony Vue. In Gomes, M. (Ed.). Embodied Knowledge [Exhibition Catalogue]. Queensland Art Gallery and Gallery of Modern Art.

Cochrane, G. (1992). The Crafts Movement in Australia: A History. New South Wales University Press.

Ely, B. (n.d.). The Murray River Project, 2009.

Harwood, T. (2022, October 19). Yuriyal Eric Bridgeman’s Language of Shield. Art Guide Australia.

Hmong American Center. (n.d.). Hmong History.

Museum of Brisbane. (n.d.). Artist in Residence: Vanghoua Anthony Vue.

Stanford Medicine. (n.d.). Hmong American. https://geriatrics.stanford.edu/ethnomed/hmong/introduction/history.html#:~:text=The%20earliest%20written%20accounts%20show,identity%20(Quincy%2C%201995)

Tapp, N., & Lee, G. Y. (2010). The Hmong of Australia Culture and Diaspora. Australian National University E Press.

Queensland Art Gallery and Gallery of Modern Art. (n.d.). Tony Albert: Visible.

Vang, T. S. (2008). A History of the Hmong: From Ancient Times to the Modern Diaspora. United Kingdom.

Vue, V. A. (2019). Frictions of Difference [Ph.D thesis]. Griffith University.