MAP Academy detail the development of India’s iconic natural dyes: madder, indigo and lac.

“Colourful, come colour me in your own hue.

You are my lord, Beloved of God.

My veil and my lover’s turban, colour them both with spring.

You are my lord, Beloved of God.

As the price you demand for the pigment,

accept the payment of my flowering youth.”

– Amīr Khusrau (1253 – 1325)

The earliest Indian cloth was an alchemical transformation of fibres from plants and animals, and pigments from the landscape — mineral and botanical — coming together through warp, weft and dyeing to create some of the earliest textiles in a range of colourfast hues. Colours and their origins have long been a part of India’s material history and its entanglement with myth, medicine, colonial science and indigenous knowledge.

Colour was no abstract concept — it was rooted in the materiality of ecosystems, fixed down and extracted through knowledge systems deeply held by certain communities. Dyeing communities who had mastered these techniques produced textiles that have been coveted both in India and around the world. Dyes and their use in textiles produced in the Indian subcontinent can be traced back four thousand years, with the earliest evidence being dyed cloth fragments from Mohenjo-Daro, in the Indus Valley, dating to the second millennium BCE. Trade of dyes may have begun in this same period, based on the traces of indigo found in Egyptian tombs and later records of trade with the Mediterranean region.

As early as the Tang Era in the seventh century, Chinese texts venerated Indian textiles for their “dawn-flushed cotton” that they compared to “sunrise clouds of morning.” In the eighteenth century, a French traveller observed that the dyes of Indian fabric would “last as long as the cloth itself” — a quality of colour steadfastness that was unparalleled at the time. Commercial activity around natural dyes reached its height during the medieval and early colonial periods in the form of block-printed and kalamkari cloth before European synthetic dyes largely replaced them.

Indian dyes were coveted not only for their vibrancy and their use in inventive textiles but also because of the carefully calibrated traditional dyeing processes, which often involved the application of mordants that fixed the colour to the fabric, making them uniquely durable. Shades of blue made from indigo; black from haritaki (black myrobalan) and khair (acacia bark); and a range of reds, lilac and burgundy made from manjistha (madder), chay root, aal (Indian mulberry) and lac insects were the longest-lasting dyes, ensuring the colours were visible on fabric thousands of years later. Yellow dyes were relatively short-lived in comparison and were made mainly from haldi (turmeric root) and to a lesser extent kusumba (safflower), palash (Parrot tree) flowers and pomegranate rind.

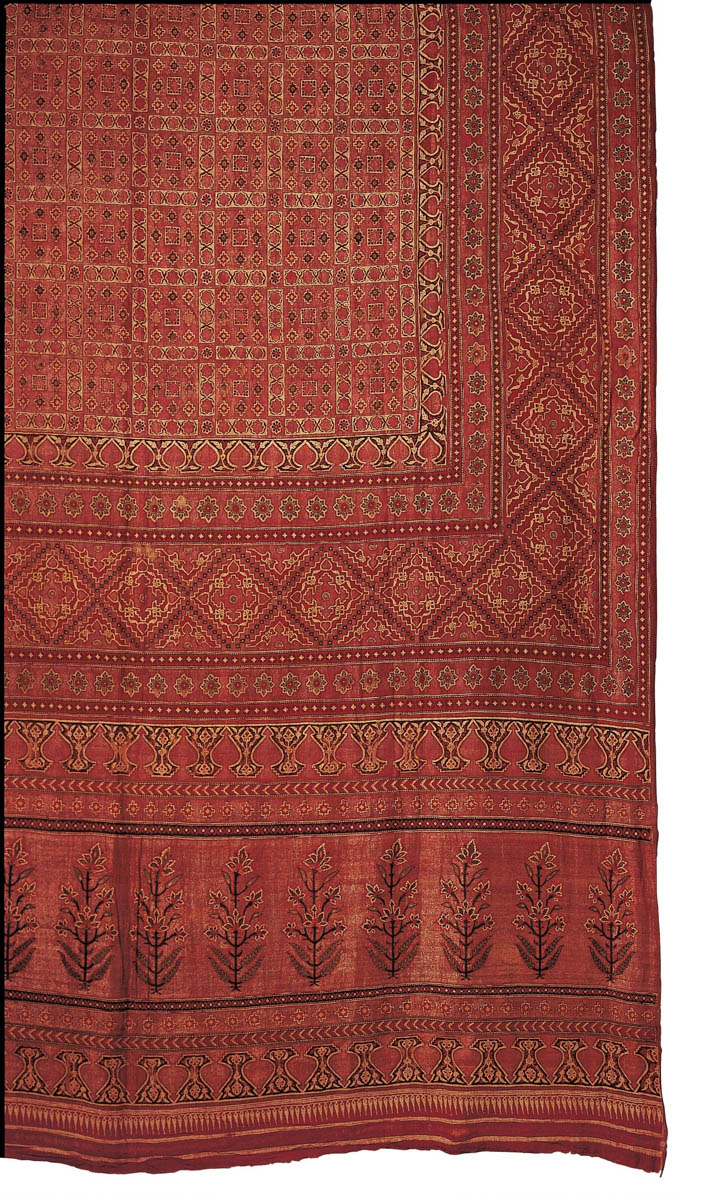

Madder Dyed Sari, Kuruppur, Tanjore District, Tamil Nadu, c. 18th century, Cotton, gold wrapped yarn; resist dyeing. Image courtesy of Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya (CSMVS)/ Google Arts and Culture.

The early discovery of natural pigments and dyes in India inspired a range of spiritual and artistic forms of expression. Religious and philosophical texts, poems, travellers’ accounts and even trade manuals shed light on the significance of prominent dyes in Indian textiles. Many raw materials used to dye textiles had multiple uses in food preparation, medicine or even temporary tattoos such as henna. Haritaki (black myrobalan), used to create shades of black, has found applications in Ayurvedic medicine for kidney and liver problems, as well as dry coughs, while turmeric remains a mainstay in Indian cooking.

To think about the histories of these natural dyes is to imagine the embodied ways in which our ancestors would have navigated the landscape — boiling the roots of the chay plant with an alkali to create a red hue, harvesting indigo leaves before the flowers of the plant bloom and then soaking them in water and churning them until they release a navy blue froth, obtaining the resinous secretion of Lac insects by tying an already lac-infested branch or twig to a tree, and periodically harvesting these as the colony expands.

We take a look at some of the most prominent natural dyes in India: their histories, the communities tied to them and their state in this contemporary moment:

Nili: The Blue of Indigo From the Bronze Age to the British Raj

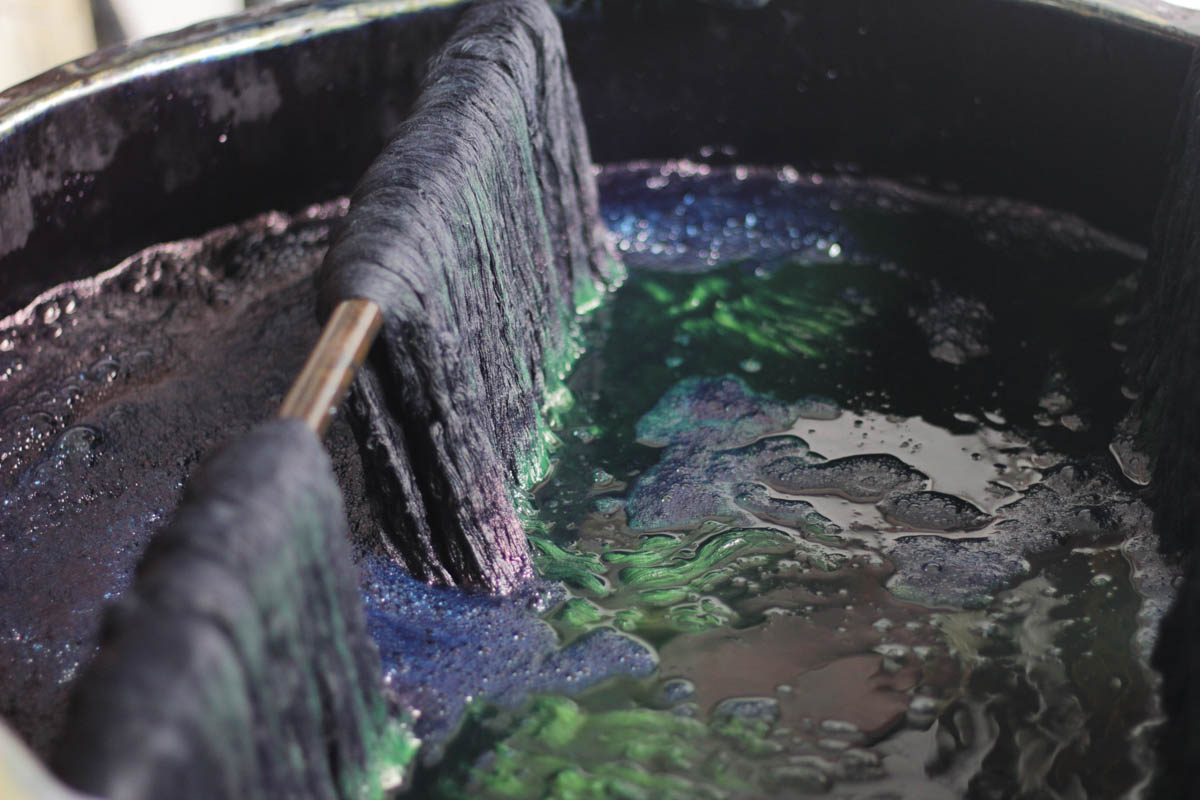

Before the flowers of the Indigofera plant bloom, artisans extract its small, green leaves, soaking them in water and agitating the mixture to release a navy blue liquid. The upper layer of the mixture is drained out and used for irrigation, while the leaves are reused as fertiliser. The water and fine sediment at the bottom of the tank are allowed to settle for a day, after which the liquid is separated from the sediment. This deep blue paste is filtered for dirt and other impurities, pressed into cakes and dried for a few days, after which the indigo is ready to be used as a dye.

Indigo powder is insoluble in water, acidic or alkaline solutions. The conventional dyeing method is to add a reducing agent such as zinc or ammonia to the hot dye bath to make indigo soluble — a state known as “white indigo” — before the cloth is dipped into it. What follows is nothing short of alchemy: on being exposed to the air, the dye bonds to the cloth in this altered state and returns to its deep blue shade after the cloth has dried. This method was typically used for dyeing whole sheets of fabric and was the prevalent method of using indigo in pre-colonial India.

Indigo Dye Bath, Akola, Rajasthan, c. 2009. Image courtesy of Craft Revival Trust Archive/ Google Arts and Culture.

The earliest material evidence of indigo dye are traces found in textiles preserved in Egyptian tombs dating to the late Bronze Age. The Atharvaveda at the start of the first millennium BCE is the first text to record a mention of the dye. It appears later in Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, a navigational text from the first century CE. A detailed description of the dye-making process was recorded around the same time by the Roman writer Pliny the Elder, suggesting that indigo-dyed textiles were being traded across the Indian subcontinent, West Asia and around the Mediterranean sea. By the late medieval period, Kabul, Aleppo, and Jeddah had also emerged as major nodes, distributing indigo to Central Asia and Persia, Ottoman Turkey and the eastern African coast.

French and British involvement in the trade took place in the Levant, where indigo prices were set for Mediterranean markets and, by extension, the rest of Europe. Despite being a very expensive dye, indigo frequently out-competed local European dyes such as woad due to its potency and fastness, leading to it being banned at various times between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries in France, Norway and Britain. For most of the medieval period, parts of present-day Gujarat, Rajasthan and coastal Pakistan produced the bulk of indigo from the subcontinent. From the sixteenth century onwards, mercantile ventures by the Portuguese Estado da India and the British and Dutch East India Companies traded indigo from these regions. Production later shifted to Bengal as the British East India Company emerged as a ruling power in the region.

The history of Indigo under colonial rule was a violent one, with British policies in Bengal, such as the Tinkathia system, making it mandatory for landowners to grow indigo in at least three kathas (a unit of land measurement) in each bigha (1 bigha = 20 kathas) of their land. These landowners (or indigo planters, as they were then known) enlisted agricultural workers who were often made to cultivate Indigofera instead of food crops. While indigo planters and British traders made considerable profits by exporting indigo to Europe and Britain, workers were compensated poorly and forced into debt, sometimes even starvation. Indigo plantations were also set up in other colonies using similar policies, particularly in the West Indies. During the Indigo Revolt of 1859, farmers from Chaugacha and other parts of Bengal staged a violent uprising against planters and zamindars. The human toll of indigo cultivation, especially in Bengal, has since been remembered as a symbol of colonial exploitation.

Indigo production declined in the late nineteenth century, when Badische Anilin- und Soda-Fabrik (BASF), a chemical factory in Germany, developed and began the mass production of synthetic indigo. By 1914, natural indigo comprised only four per cent of global indigo usage. The vast majority of indigo is now synthetic and is used for dyeing denim, although some natural indigo continues to be produced in south India, particularly Karnataka.

Revivalists including institutions such as Nila Jaipur and artists like Kaimurai have incorporated indigo into their craft and art practices. Kaimurai is the moniker—translating to “method of hand”—adopted by visual artist Abhisek GJ, through which he explores his love for natural indigo, creating expressive works using indigo on khadi cloth in which the pigment’s many hues—from near-black to bright blue—became apparent.

Madder Dye: Staining Cotton Red in Mohenjo-Daro

Dyeing the Yarns in a Light Shade of Red Using Madder, Tripuradevi, Uttarakhand, c. 2017. Image courtesy of the Avani Society, Berinag, India/ Google Arts and Culture.

A natural red colourant extracted from the roots of the Indian madder or manjistha (Rubia cordifolia) and common madder (Rubia tinctorum), madder dye is known for its vibrancy and fastness.

Indian madder is a cultivated species of madder that contains high amounts of alizarin, which is the main compound responsible for producing red in most natural dyes. Common madder is native to West Asia and the Mediterranean region and has been grown and used as a dye across Asia for centuries. The widespread habitat of madder plants as well as the long history of the trade of Indian cotton cloth has resulted in multiple varieties of madder being cultivated and used throughout Southeast Asia, South Asia, the Mediterranean coast and northern Africa.

Madder has been used across the Indian subcontinent since the second millennium BCE. The dye was also found on textiles discovered in the tomb of the Egyptian pharaoh Tutankhamun, dating to the fourteenth century BCE. Textiles dyed, painted and block-printed with madder as well as other red dyes, such as those derived from lac, Indian mulberry and safflower, were also regularly exported to eastern Africa, West Asia and Southeast Asia from the first millennium CE onwards. Indian trade textiles, such as Chintzes, kalamkaris, Indiennes, Guinea Cloths, Palampores and Calicos coloured with madder and Indigo were extremely popular in Europe during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Madder dye began to be directly exported to Europe after cotton cloth began to be produced there.

The roots of the madder plant are gathered when it is between two and five years old. They are then cleaned and crushed into powder or tiny fibres. In pre-industrial India, soft water was first heated without bringing it to a boil before adding the cloth and salt- or oil-based mordants, preferably alum, to the water. The cloth was then allowed to sit in this solution as it cooled, before being removed and wrung. A dye bath was then prepared by wrapping the crushed madder in a cotton cloth and placing it in a separate vat of water, followed by the mordanted cloth. Since alizarin has low solubility in water, this method allowed the red colour to disperse through the water slowly, so that the bath was evenly coloured and the cloth dyed uniformly. The dye bath could be reused to obtain lighter shades of red or pink.

Soaking the Madder Roots, Tripuradevi, Uttarakhand, c. 2017. Image courtesy of the Avani Society, Berinag, India/ Google Arts and Culture.

Madder dye was replaced by synthetic dyes by the late nineteenth century. Today, the dye is used to a small extent in traditional textile craft, specifically on block prints such as bagru, ajrakh, farrukhabad prints, kalamkari, and machilipatnam prints, and also a natural dye for yarns before they are woven into cloths like Patolas or Odisha Ikats.

Lac Dye: Burgundy From the Resin of a 100,000 Insects

Lac Obtained from the Resinous Secretion of the Lac Insects, Tripuradevi, Uttarakhand, c. 2017. Image courtesy of the Avani Society, Berinag, India/ Google Arts and Culture.

A water-soluble colourant, lac dye is usually red to burgundy in colour and is extracted from a resin produced by the Kerria lacca and Laccifer lacca insects. Lac dye is used for dyeing wool, silk, and colouring food. The word “lac” derives from the Sanskrit laksha, meaning “100,000”, referring to the large number of insects typically needed for making the resin, dye and their byproducts. Lac was known in the subcontinent from at least the first millennium BCE. It is mentioned in three texts from the period: the Atharvaveda, the Astadhyayi of Panini, and the Mahabharata, where the Pandavas are almost killed in a flammable building made of lac resin and ghee. A dye recipe for lac is found in the Nayadhamma Kaha, a fifth-century CE Jain text. Lac dye has been used in woollen Persian carpets since the eighth century and was introduced to Europe in the late sixteenth century through Portuguese agents in India.

Lac insects have a parasitic relationship with trees such as the Indian jujube (Ziziphus Mauritiana), kusum (Schleichera oleosa) and palash (Butea monosperma). The insects infest the trees by piercing the bark and drawing nutrients from the interior. The resin secreted by the insects can be processed into shellac. This can be shaped into jewellery or used to finish wooden surfaces, which is why lacquer was originally made with lac. Lac insects are cultivated by tying an already-infested branch or twig to a tree, and periodically harvesting these as the colony expands across the tree. Today, lac is cultivated primarily in the states of Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh, Bihar, Odisha and West Bengal, often by Adivasi populations in forested areas.

Lac dye gets its red colour from the laccaic acid present in the hemolymph or body fluid of the lac insect. It is obtained by separating the insects from the branch and the resin, crushing them and dissolving the result in an alkaline solution. This solution is then acidified and treated with chalk, which reforms the dissolved dye as a sediment. The sediment is allowed to settle for a week. The resultant crystallised form of lac dye is then strained out and added to a hot dye bath while still damp. A mordant, ideally tin chloride and the fabric to be dyed are added to the bath and allowed to sit for an hour as it simmers. After the colour has reached a sufficiently deep shade, the cloth is removed, rinsed and allowed to dry.

In contemporary times, lac continues to be produced as a cash crop across southern Chhattisgarh by communities who generally live in the fringes of forests. Because the Lac resin is an essential component in a host of industrial products ranging from pharmaceuticals, electronics, sealants dyes, paints and polishes, it has become a means for these communities to earn a living.

Read more about India’s natural dyes here.

Read more about India’s block printing traditions here.

This article is provided by MAP Academy and is drawn from their cluster Understanding South Asia’s most recognisable dyes.

Comments