Gu Yuan. Learn a Thousand Characters (1943). Colour woodcut. 13 x 12.8cm. Image reproduced from the National Gallery of Australia. (n.d.).

Pamela See considers the key political role played by woodcut prints in Chinese communism.

Craft exists at the boundary between the natural and artificial. Cultivating conceptions, when it comes to the perceptions of significant proportions of populations, is a craft rarely honed and its occurrence is, by definition, historical. As in any craft practice, there are latitudes of success. In 1879, for instance, Lowe Kong Meng, Cheok Hong Cheong and Louis Ah Mouy, skilfully addressed what may be considered a natural conception that all Chinese people are “uneducated” “filthy” “barbarians” in The Chinese Question. Most readers would be impressed by the eloquence with which their convictions were conveyed. Yet the influence of any unillustrated document, irrespective of how well crafted, has a comparatively limited audience. In the face of the graphic illustrations circulated by the vindictive New South Wales press of the late Victorian Era, the leaders of the Chinese Australian community were able to garner little resistance to the xenophobia being proliferated.

Over two centuries post-federation, sinophobia remains salient. Yet a quiet resistance is being channelled through the museum and galleries sector, including the National Gallery of Australia. The Peter Townsend Collection of Chinese woodcut prints was acquired from the founding editor of Art Monthly in 1985, who sojourned in China between 1941 and 1949. It houses a set of 新窗花 [New Window Flowers], which evidences a commitment towards gender equity, education and hygiene. Aside from presenting Australian audiences with a narrative contrary to its mainstream media, the seminal artworks bear witness to the conception of a new craft that would, in turn, play an integral role in the shaping of a new national identity.

The People’s Republic of China was wrought through the defence against incursions from foreign forces on military, cultural and economic, fronts. The New Window Flowers embody the process through which the Communists of the 1940s crafted their distinct ideology. The raw materials they engaged in included socialist values and visuals which its European enemies had sought to dispose of within their own geographic region. However, their infusion required emulsification within the principles and pictorial conventions precious to the proletariat who made up a vast majority of the population. According to the poet Ai Qing and woodcut artist Jiang Feng, the medium of papercutting provided an appropriate vehicle to carry social realism to the masses.

Lu Xun, the father of modern Chinese literature, introduced the style to China through the woodcuts of Kathe Kollwitz. The artist purportedly permitted him to reproduce Das Opfer [The Sacrifice] in the inaugural 北斗杂志 [Beidao Magazine] published on 20 September 1931. Additionally, in December 1932, he exhibited prints from the Ein Weberaufstand [Weaver’s Revolt] series of etchings in a Shanghai bookstore. The Chinese forebearers of woodcut had engaged the medium for a myriad of functions, including creating government-sanctioned historical records and proliferating religious doctrine. In the absence of formal religious association, many Chinese people retained, at minimum, superstitious beliefs which led to the widespread posting of 年画 [New Year Pictures] for good luck. However, despite the Nationalists’ efforts to deter these feudal practices, they saw the alternative woodcuts as revolutionary and sought to extinguish the movement. Although Lu Xun was never officially aligned with the Communists, the Lu Xun Academy of Fine Arts was nonetheless established in Yan’an in 1938.

- Xia Feng. Yangge (1943). Colour woodcut. 12.8 x 12.8cm. Image reproduced from the National Gallery of Australia. (n.d.).

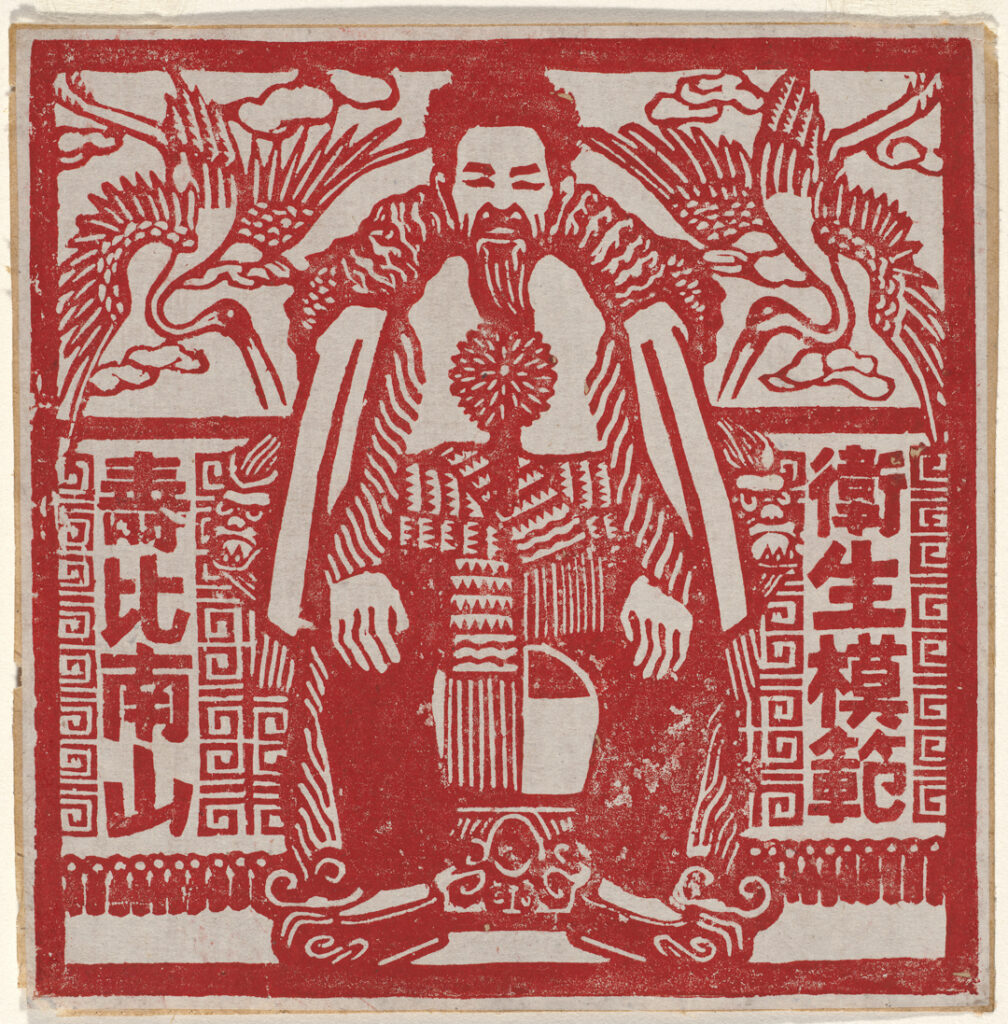

- Luo Gongliu. Follow the Hygiene Example: Live as Long as the South Mountain (1944). 13 x 12.8cm. Image reproduced from the National Gallery of Australia. (n.d.).

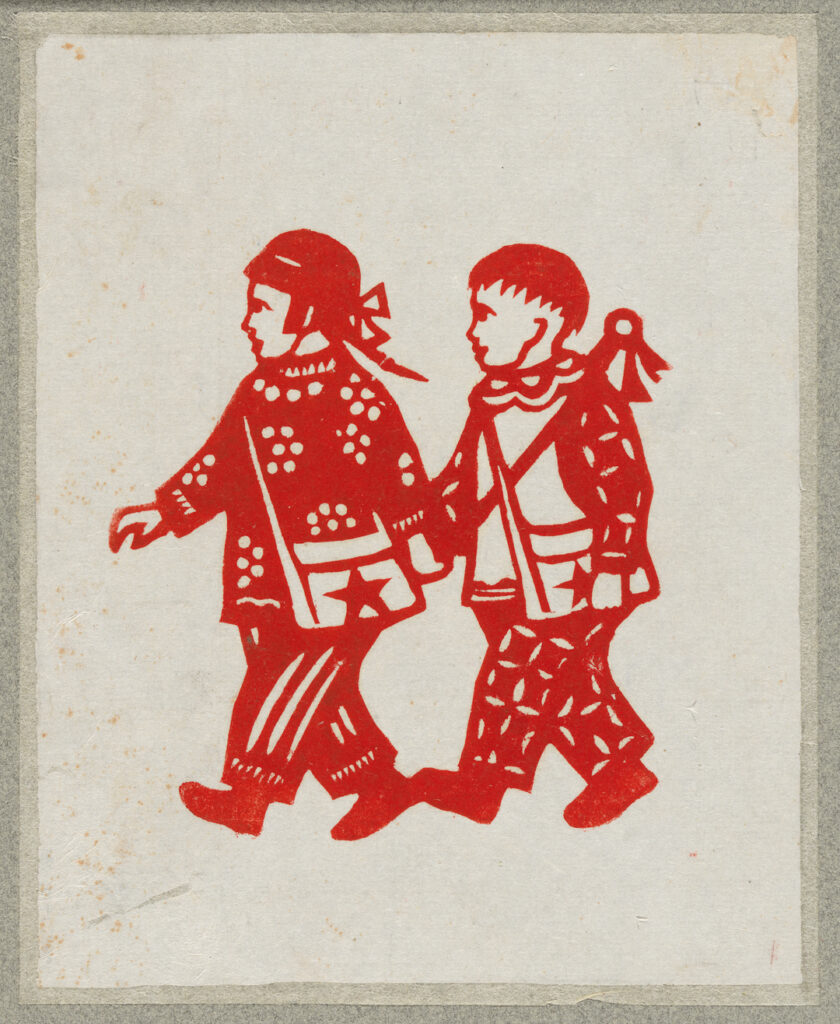

- Gu Yuan. Going to School (1943). Colour woodcut. 9.2 x 8.3cm. Image reproduced from the National Gallery of Australia. (n.d.).

In May 1942, Mao Zedong cemented his leadership of the Communists and defined their policy on the arts for the proceeding half century through his delivery of a speech at the Yan’an Forum on Literature and Art. Amongst his advice to artists was to “draw nourishment from the masses”, engage “the raw materials of life” and create “the highest possible perfection of artistic form”, which reflected a “unity of politics and art, unity of content and form, [and] unity of revolutionary political content”. As a consequence, Ai Qing and Jiang Feng took a group from the Lu Xun Academy of Fine Arts to the villages Yanchi, Dingbian and Jingbian, in February 1943. Amongst the urban artists were Gu Yuan, Luo Gongliu and Xia Feng, all of whom feature in the Peter Townsend Collection. Although Ai Qing collected some papercuts, a majority of what would become the 西北剪纸集 [Northwest Paper Cut Collection] was retrieved in December 1943. In 1944, over 100 papercuts and woodcut prints, including examples produced by Gu Yuan and Luo Gongliu, were showcased at a Shaanxi-Gansu-Ningxia Border Region conference on culture and education. The prints, which embedded the aesthetics and symbolism of the papercuts, became known as New Window Flowers. This amalgamation in genres was also celebrated in the Woodcut Paper Cutting Exhibition at the Xingxian Border District Guest House in 1946.

Ai Qing appeared to recognise that the power of papercuts lay as much in the symbolism it engaged as its distinctive aesthetics. Accordingly, he allowed some papercuts with allegorical references to be exhibited. However, emphasis was placed on papercuts and prints which furthered a social realist agenda. Notably, his counterpart Jiang Feng would reframe many of the aforementioned papercuts as “traditional” in his exhibition and accompanying book 延安剪纸 [Yan’an Papercuts]. The exhibition was staged at the National Art Museum of China (NAMOC) in Beijing in 1980, and the book was published by The People’s Fine Art Publishing House a year later. The dialogue between the Lu Xun Academy of Fine Arts artists and papercutters served to sinicize the German Expressionistic woodcut style of the former with scissor marks of the latter such as “saw tooth” and “sun pattern”. It also added an aspirational aspect, conveyed through symbolic representations of flora and fauna. By contrast, papercuts diversified in subject matter to include overtly autoethnographic, at times autobiographical, elements. Henceforth both came to capture Chinese modernity, with particular reference to depicting the impact of Communist reforms on the living standards of the proletariat.

Amongst the prints in the Peter Townsend Collection, which number over 280, there are at least five of Gu Yuan’s New Window Flowers which also featured in Ai Qing’s seminal showcase in 1944. Characteristic of papercutting aesthetics, most are figures without grounds and by and large elevate the status of women. Their contribution across the domestic, industrial and agrarian, spheres is celebrated. In contrast to Kollwitz’s depictions of weavers, who are wretchedly protesting or resigning to their destitution, the young woman in Spinning (1943) appears industrious and content. There are many depictions of healthy children including Going to School (1943). In it a girl leads a boy. He is carrying a large knife for protection, as was required in the areas liberated from Japanese occupation. The composition is in stark contrast, in content and intent, to the papercuts and woodcuts with children used to celebrate the new year. These typically feature cherub-like boys frolicking with totemic flora and fauna. Gu Yuan constructed narratives featuring self-determined people, who make their own fortune as opposed to hoping for good luck.

The book 西北剪纸集 [Northwest Paper Cut Collection] written by Ai Qing and Jiang Feng, published in 1949, depicts a number of prints featuring solid square borders, including Gu Yuan’s Learn a Thousand Characters (1943). The print depicts a woman learning to read and write amongst sunflowers, a symbol of vitality and intelligence. The composition may also reflect land reforms, the property redistribution in which women were able to partake as prospective proprietors.

Another example is Xia Feng’s Yangge [Folk Dance], which illustrates the importance of yangge (秧歌) as a medium for proliferating leftist values and recruitment. With the male subject carrying a banner, emblazed with the Chinese characters for “the army”, the folk dance depicted in this composition appears to be encouraging women to join it. At a time when the effects of foot binding remained salient, the embroidered shoes of the female subject are notably large. Farther still from the Confucius requisites for feminine beauty, the woman is bigger than her male counterpart. Yet the pair are juxtaposed by a sunflower and magpie, the latter a symbol of happiness.

Chinese women did serve on the frontlines for the Red Army, and Chinese Australian women in the 2nd Australian Imperial Force in World War II. However, at the time feminism in Australia was between its first and second waves. The requirement for women to fill roles vacated by men serving in World War II was a catalyst for the latter. It was not until the Whitlam Government of the 1970s that genuine reform on gender equity began occurring in Australia.

Whereas the prints by Gu Yuan and Xia Feng in the Peter Townsend Collection focus on elevating the status of women, Gu Yuan’s colleague from the Lu Xun Academy of Fine Arts, Luo Gongliu, also produced a woodcut print addressing the health of men. In Follow the Hygiene Example: Live as Long as the South Mountain (1944) a proletariat man is placed central in the composition, on a throne-like chair, surrounded by symbols for longevity including storks and chrysanthemum. This treatment of the subject is akin to the presentations of deities in 纸马 [zhi ma] prints.

Emerging in the Tang Dynasty (618–907 CE), this folk art of printing joss paper was one of the earliest applications of woodcut. Literary accounts of the appearance of zhi ma shops date back to the Song Dynasty (960–1279 CE) book 东京梦华录 [Tokyo Dream Hualu] by 孟元老 [Meng Yuanlao]. The prints would displace the papercutting of offerings for the deceased. Although the medium continued to evolve during the Yuan and Ming Dynasties, a major expansion in the pantheon represented occurred during the Qing Dynasty (1644–1911 CE). This reflected the diversification of professions and the desire for practitioners of each to worship their own deities, with the industry-specific “gods” including Cai Lun for papermakers and Lu Ban for carpenters.

Gu Yuan. Spinning (1943). Colour woodcut. 8.5 x 11.3cm. Image reproduced from the National Gallery of Australia. (n.d.).

Although papercutters rim their compositions to cohere cut elements using a variety of shapes, zhi ma prints are characterised by their thick square borders. This rhetoric of a solid square frame consecrating its contents may date back to the 221 BCE unification of China. At his removal of the Warring States, Qin Shi Huang introduced imperial seals featuring the pictorial device, the carving of which has evolved into contemporary name chops. According to folklore proliferated by the occupying Mongol regime during the Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368 CE), a jade seal fashioned for Emperor Qin reappeared in 1294, evidencing their divine mandate to rule. Notably, aspiring woodcut artists in Hangzhou in the 1930s, after experiencing Lu Xun’s first woodcut exhibition, sought instruction from seal engravers. The solid frames also further the realist rhetoric of the New Window Flower prints. In an Albertian context, the audience is assigned a vantage point, a window through which to witness the narratives unfold.

In The Good Earth, penned by American author Pearl S Buck in the 1930s, the protagonist Wang gleefully returns to the life of an unwashed farmer. Although this daughter of Presbyterian missionaries based in China may have presented a sympathetic perspective, the book nonetheless perpetuates the myths of Chinese people being unclean. A predecessor, Baptist missionary Arthur Henderson Smith, published a treatise on the differences between Chinese and American people in 1894, at the height of his government’s efforts to exclude Chinese migrants. In Chinese Characteristics he stated:

The complete ignorance of the laws of hygiene which characterizes almost all Chinese… are well known to all foreigners who live in China… it is a standing problem why the various diseases… do not exterminate the Chinese altogether.

The sentiments gained salience alongside the concept of “race”, which was posited in the late eighteenth century by German physician and anthropologist Johann Fredrich Blumenbach and gained traction in the nineteenth century. Prior to this time, polygenists believed that non-Europeans were of a separate species. Irrespective, a national approach to healthcare in China including state-run hospitals, policed sanitation laws and public health campaigns, was established in the first three decades of the twentieth century. The latter mirrored the development, in timeframe and content, of a preventative approach to health care, through a focus on promoting hygiene, in North America during the end of the 1910s and early 1920s. The print by Luo Gongliu serves to demonstrate a longstanding commitment to public health held by the Communists since the 1940s.

Ai Qing, Jiang Feng and the artists from the Lu Xun Academy of Fine Arts, built upon 唇花 [window flowers], a papercutting tradition endemic to Shaanxi province, by infusing it with the realism of German expressionism. However, like Lu Xun who advocated for both traditional and foreign woodcuts, they also incorporated elements from other indigenous printmaking forms such as zhi ma and seal carving. New Window Flowers have immediacy, authority and authenticity, which have been enhanced through their reproduction using offset printing. This resonance may reflect the innate rawness, the retention of the wood grain and the deliberate crudeness of the cut lines, which draws attention to the processes engaged in the production of the original prints. Their broad distribution reified both the status of papercutting as a rhetoric for rural women and their contents which often addressed the concerns of the same demographic.

Through the prints in the Peter Townsend Collection, we witness the birth of a modern China, and a progression in the policies of health care, education and gender equity, which rivals the development of many countries including our own. The discrepancies between the portrayals of Chinese people in this medium and the present Australian mass media draw attention to the artifice of both, and the danger in assuming either is a result of natural consequences. Every conception is carefully constructed and in the domain of public perception crafted by writers, artists and orators.

This essay draws on material presented at the international workshop initiated by Claire Roberts, Associate Professor of Art History and Curatorship at the University of Melbourne: “Artists Look at Art: Activating the Peter Townsend Collection of Chinese woodblock prints at the National Gallery of Australia” held at the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, 29-30 September 2022, supported by the National Foundation for Australia-China Relations.

Images courtesy of National Gallery of Australia. (n.d.). Search the Collection.https://searchthecollection.nga.gov.au/landing. Peter Townsend Collection, purchased with the assistance of the Australia- China Council, 1985.

Further Reading

Ai, Q. & Feng, J. (1949). Xibei jianzhi ji (Collection of Northwestern Paper-cuts). Chenguang Chubanshe.

Bevan, P. (2020). ‘Intoxicating Shanghai’ – An Urban Montage: Art and Literature in Pictorial Magazines during Shanghai’s Jazz Age. Brill.

Blumenbach, J. F. (1775). De Generis Humani Varietate Nativa. Frid. Andr. Rosenbuschii.

Bories, E. (2016). The Influence of Käthe Kollwitz on Chinese Creation: Between Expressionism and Revolutionary Realism. In Bazin, J., Glatigny, P. D. & Piotrowski, P. (Eds.). Art Beyond Borders: Artistic Exchange in Communist Europe (1945-1989) (1st ed., pp. 453–459). Central European University Press.

Buck, P. S. (1931). The Good Earth. John Day Co.

Chinese Museum. (n.d.). WWII Chinese-Australian Soldiers Honour Roll.

Corban, C. (2015). Lu Xun (1881-1936) and the Modern Woodcut Movement. Bowdoin Journal of Art.

Feng, X., & Wang, F. (1998). Art Handbook. Shanghai Fair East Publishing House.

Herbert, F. (1978). From Tribal Chieftain to Universal Emperor and God : The Legitimation of the Yuan Dynasty. Verlag der Baerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften.

Hilton, T. (2006, July 26). Peter Townsend. The Guardian.

Huang, Y.C. (2014). The Origin, Classification and Evolution of Chinese Paper Cutting. [Ph.D Dissertation]. University of Leeds.

Jiang, F. (1981) Yan’an jianzhi (Yan’an paper-cuts). Renmin Meishu Chubanshe.

Kun, Z. (2014, August 8). German Expressionism on View in Shanghai. Shanghai Star.

Kurlansky, M. (2016). Paper : Paging Through History. Thorndike Press.

Lu, X. (1931, September 20). 牺牲——德国珂勒维支木刻〈战争〉中之一. 北斗杂志 Beidao Magazine, 1(1).

Manping, L. (2016). The Influence of the Yan’an Literary and Art Forum on the Development of Paper-cutting Art in Northern Shaanxi. Journal of Shaanxi Preschool Normal University, 6 (2016).

Mao Zedong. (n.d.). Talks at The Yenan Forum on Literature and Art: May 1942. Selected Works of Mao Tes-tung.

Mouy, L. A., Cheong, C. H. & Meng, L.K. (1879). The Chinese Question in Australia, 1878-79. Bailliere.

Pollard, D. E. (2002). The True Story of Lu Xun. The Chinese University of Hong Kong Press.

Qiao, X., & Dong, Y. (2018) The Spirit of Practice: Research on the Curriculum Model of Chinese Folk Art and Intangible Cultural Heritage. Jiangxia Fine Arts Publishing House.

Smedley, A. (1984). Chinese Woodcuts 1935-49. The Massachusetts Review, 25(4). 553–564.

Smith, A. H. (1894). Chinese Characteristics. Fleming H. Revell Co.

Stranahan, P. (1983). Yan’an Women and the Communist Party. University of California.

Sun, S. H. (1974). Lu Hsün and the Chinese Woodcut Movement, 1929-1936. Stanford University.

Wilcox, E. (2020). When Folk Dance Was Radical: Cold War Yangge, World Youth Festivals, and Overseas Chinese Leftist Culture in the 1950s and 1960s. China Perspectives, 120(1). 33-42.

Wong, S. (2020, February, 20). Sinophobia: How a Virus Reveals the Many Ways China is Feared. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-514560564

Wu, K. (2015). Reinventing Chinese Tradition: The Cultural Politics of Late Socialism. University of Illinois Press.

Yang, C., Tsai, T.C. & Chuang, M. C. (2016). Amorphological Analysis of Joss Paper Image in Taiwan – A Case Study of Fu Lu Shou. Journal of Language and Culture, 7(2). 10-17.

Zhang, D. (1989). The Art of Chinese Papercuts (1st ed.). Foreign Languages Press.

何, 马玉涓. (2019, May 13). 纸马民间艺术论文. 文秘帮.