Last year’s Te Moana nui a Kiwa issue was anticipated by the release of the Moana Disney animation. Normally, this kind of popular culture would seem in a different league to the serious realm of material culture. But the film was hailed for its level of consultation and involvement from the Moana community, though this didn’t prevent it receiving some criticism for its simplification of cosmology and demeaning portrayal of the god Maui.

Wouldn’t you know it? This year’s Mexico issue is also anticipated by a Pixar animation: Coco. Based partly on the town of Oaxaca, where we’ll be hosting our own mini-festival, Coco concerns a boy who strives to become a musician, emulating the memory of his grandfather, Ernesto de la Cruz.

The scenes moving into and out of the afterlife are mesmerising. I had to watch it again the next night just to experience the wonder again. But I knew that something wasn’t right.

Riviera family turned their back on music after he abandoned his family to seek glory. Instead of music, they reverted to shoe-making, which is portrayed as a menial task for dullards. The craft of shoemaking was too easily set up as a backward restraint on the boy’s development. His “dream” of becoming a musician, fitted too comfortably in the Hollywood fantasy of Disney, where entertainment allows you to escape the ordinary world. It all looked too much like an exercise in cultural imperialism: pointing the way forward not in the self-sufficiency of home-grown industry but in the consumption of corporate entertainment fare from the USA.

I shook my head at the ideological switch perpetrated by Disney. The film purports to be a celebration of family, as the boy reconnects the pieces of his broken past. But this masks the fact that he is diminishing the family as a social unit by refusing to continue its craft tradition. It was a Slavoj Zizek 101 exercise in ideological deceit.

I took to Google expecting to find critiques that echoed my own, particularly from Mexicans themselves. Nada. There has been some criticism earlier on when Disney attempted to trademark El Dia de los Muertos, but Disney received such an outcry that they quickly backtracked. I couldn’t find anything like the subtle cultural criticism from Moana experts about their Pacific animation.

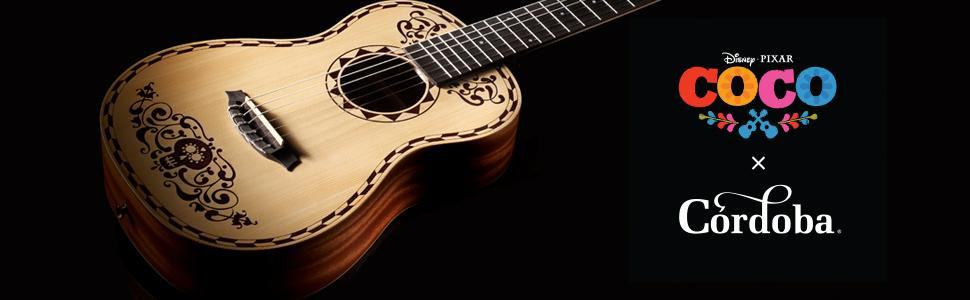

To my surprise, I discovered that Coco had quick a positive impact on craft. The fluorescent creatures that fly around the underworld were based not on ancient mythology but on the craft of alebrijes, featuring figures carved from wood. It’s a specialisation of Oaxaca, drawing from its nahuatl culture. Also, the opening scene features animated paper cutouts (similar to the way tattoos were used in Moana). The papel picado is a distinctive feature of Mexican festive craft. And finally, the white decorated guitar that is the coveted instrument of Miguel is now in hot demand from Mexican luthiers.

Ah well. That’s entertainment. Just as we secretly love the monsters, even the demeaning depiction of craft has the effect in the end of bringing it to our attention.

I watched this film (twice) thinking about the event that’s being organised for Garland by our Mexican partners in Oaxaca. It’s a unique opportunity to learn more about the vivacious crafts featured in Mexico. But what about El Dia de los Muertos? I looked at the invisible dead in Coco who visit the cemeteries at this night and wondered if that’s how we will feel when we move among those who are participating in this event. Will we be like ghosts, enjoying the spectacle, but in a different reality? No doubt, we will come away with an amazing memory that will stay with us for the rest of our lives (and perhaps beyond). But what do we contribute to this event?

https://youtu.be/p43fx_smRGE?t=56s