What is the role of critical craft thinking and how can it honour the knowledge embedded in making itself?

The early days of the 2020 lockdown were revelatory. A compelling video emerged of a toddler sauntering into his father’s study as he was being interviewed live on BBC television. The comic confusion of domestic and office spaces did highlight the mobility of knowledge work. What previously was seen as the domain of a formal office, with board rooms and water coolers, was shown to be possible anywhere, particularly with Zoom’s green screen.

It’s not necessarily the same in a material practice such as the crafts. Makers face the sudden closure of shops, cancellation of major international fairs which would otherwise bring an annual income, and critically the suspension of classes that had become an increasingly important source of revenue. The main focus of Garland magazine has been to find ways to help makers survive this, such as the Ring Project. But for me personally, it has brought into relief the issue of what it means to be a knowledge worker in the crafts.

Crafts, like most pursuits, has its own knowledge workers, including journalists, curators, academics, editors and online “content creators”. Given the rise of post-graduate education, many of these are increasingly practitioners as well. But cleary knowledge workers don’t have to make objects themselves (I do attempt this myself, where possible, if only to remember how difficult it is).

The concrete value of making in crafts does problematise the role of abstract knowledge work. As we see in the countless forms we need to fill out, knowledge can seem like the extraction of time and value for external uses. This prompts the question of how knowledge work can be seen as something “in service of the crafts”.

What is a knowledge worker?

As articulated recently in Jeremy Lent’s Patterning Instinct, Western civilisation predominantly privileges the production of abstract knowledge. In the Platonic framework, philosophy provided unique access to the fundamental truths from which the material world was a mere byproduct. Aristotle divided the realm of contemplation (theoria) from action (askholia). A parallel hierarchy in Western civilisation set the pure priestly class against those involved in corrupt worldly activities.

The secular version of this emerged during the Enlightenment which played an active role in fomenting social change, particularly as the “fourth estate” in the French Revolution. It has provided heroes of modernity, such as George Orwell, Naomi Klein and Julian Assange.

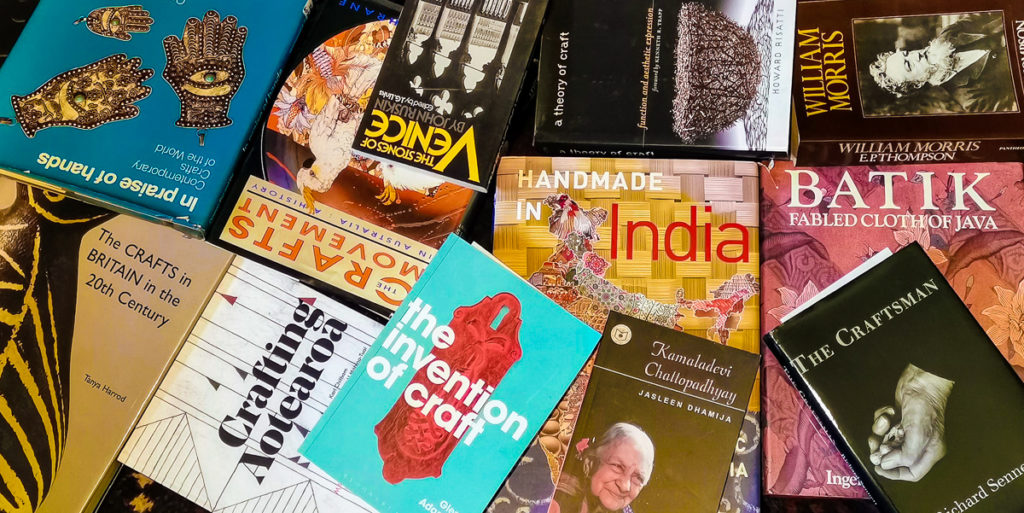

As outlined in Glenn Adamson’s The Invention of Craft, this hierarchy was sustained in industrialisation when the mechanisation of labour enabled the rise of a managerial class whose power superseded the material knowledge of workers. This parallels the growing conceptualisation of the “fine” arts, which elevates the role of writers and curators—particularly evident in grand statement biennales such as that in Venice.

Sociologically, this hierarchy is played out in access to tertiary education. The length of formal education contributes strongly to social status. Accordingly, craft learning has evolved from apprenticeship in workshops to formalised degrees in universities.

Politically, the “knowledge class” has redefined membership of parties. Leftwing parties are now mostly for voters with higher education, which has prompted those without degrees to support right-wing populists who speak a language they can understand. Thomas Picketty recently described the knowledge class as “an educational elite (or ‘Brahmin left’) that stands for cultural diversity, but has lost faith in progressive taxation as a basis for social justice.”

It’s certainly possible to see knowledge workers as a parasitic class. They are easily depicted as latte-sipping elites, indulging in virtue-signalling, unpatriotic and looking down on “cashed-up tradies”.

I was prey to this perception at my very first public “outing” as a craft knowledge worker, during the opening of Symmetry: Crafts Meet Kindred Trades and Professions. The gallery director introduced me as the curator without mentioning the names of the artists who made the work. It rightly raised the hackles of the craftspersons present, who saw yet again the disdain in visual arts for those who make things with their own hands. Rarely do you see the names of the “technicians” who actually made the work of artists like Ai Weiwei. The visual arts establishment reproduces a class hierarchy that values conceptualisation above realisation.

So how can knowledge work in service of the crafts acknowledge the value of making objects, including the intelligence that comes for a skilled knowledge of materials? To answer this, we need to look at what knowledge work actually entails.

What is knowledge work?

The most visible role for a knowledge worker in the crafts is to advocate for the value of craft. Richard Sennett’s The Craftsman is preeminent in articulating the value of craft in modern society beyond its traditional association with the pentad of clay, metal, fibre, wood and glass. Besides putting craft in the bookshop, they can be heard on radio and video.

This is important internal work to do as well. Artistic activities have meaning when they are part of a defined field of collective endeavour. This offers creators with the opportunity to contribute to a forum of creative work across time and space.

Knowledge workers can play a role in making the connections that build this shared field. One process is to develop concepts that abstract meaning from works and gather them together. The concept “eco-craft”, for instance, offers a shared identity to whose makers who attempt to include sustainability in their production.

Beyond these horizontal connections, there is also the business of developing narratives that speak for the development of a field over time. The dominant story in visual arts has been the modernist quest to free ourselves from inherited ways of seeing.

While this story does underpin much studio craft, it is at odds with crafts that rely on material learning across generations. One of the great challenges for knowledge workers in service of the crafts is to propose an alternative narrative that is appropriate to craft practice. An exemplary case for me is the work of the New Zealand scholar Damien Skinner (sadly retired now). As director of Art Jewelry Forum, he helped develop the field of contemporary jewellery through tools such as the narrative of “critique of the preciousness”. There is certainly much more work to be done in developing narrative projects that are relevant to the crafts.

There are also more mundane functions. As well as developing connections, there is the inevitable gate-keeping. This is implicit in the choice of artists to include in exhibitions and writing, as well as roles in judging for competitions and assessing grant applications.

Meanwhile, there is an incessant activity of information gathering and sharing. The abstract nature of knowledge work enables it to function like a bee, gathering the pollen from many sources, enabling cross-pollination and the “honey” of publications.

For many, knowledge work is associated with academia. Journals, chapters and academic books provide an important archive for the field. But often their value as knowledge is limited to institutionalised economies of knowledge. The emphasis on citations leads to a “house of cards” whereby articles are assembled from references to previous journal articles. It just takes one author to claim a craft revival for this to become cite-able and then a building block for other articles. Despite this infrastructure of citations, there is rarely a critical examination of its argument.

Deep knowledge work involves what Hegel called “the labour of the negative”. The strength of an argument depends on an understanding of its counterpoint. This is scientific in the broader sense of constructing falsifiable hypotheses that become stronger by being open to scrutiny.

Rather than an accumulation of citations for craft revival, it is more meaningful to consider carefully the case against it. Take for example there is a prevalent perception that craft is a “backward” pursuit that belongs in the past. Rather than automatically take a reactionary position, it is more productive to explore the premise of “backward”. How did the linear concept of time evolve? What are its alternatives? Such questions will not produce a simple “yes” or “no”, but a more nuanced understanding of the conditions in which there might be progress or not.

In view of this, we might consider three pillars of knowledge work in service of the crafts. In the spirit of falsifiable hypotheses, they are erected to invite counter-argument in the hope that a stronger partnership might emerge between thinkers and makers.

1. To support the value of craft in the world today

Craft is challenged by modernity at a number of levels. It draws on traditional practices in the past. It is slow and inefficient. It cannot be scaled to mass markets. It is not easily represented on the screen, and so on. A knowledge worker in service of the crafts must transform these negatives into positives and thus give dignity to those who commit their lives to practising craft skills.

But in doing this, crafts must be championed as activities worthy in their own right. There are many ways of elevating craft as worthy of being seen as art, which implicitly demean what makes craft unique. The knowledge worker should aim to give craft an autonomous value.

2. To respect material knowledge

In championing crafts, knowledge workers are often speaking to others in the knowledge class, such as editors, gallery owners and organisation directors. It is easy to draw on information from secondary sources, such as academics, publicists and journalists. This is supported by the logocentric nature of Western thought that privileges the word above the action (think of the distrust that has accrued to the term “master”). This has sometimes been disparaged by makers as “craft talk for the dinner party”, where it is used as a signal for authenticity within the knowledge class rather than a conversation that includes makers themselves.

A knowledge worker in service of the crafts gives at least equal legitimacy to the wisdom that has been gained through making. This means the sourcing of information from craftspersons themselves and always attributing their work in forms such as photo captions.

3. To ask difficult questions

There is much advocacy for crafts in public discourse. This includes inspiring stories of dying crafts that are “rescued” or increased interest in making and return to old practices of “repair”. And there are countless manifestos about craft as a pathway to a better world. These are worth promoting, but a knowledge worker needs to dig deeper to understand the situation from all perspectives. This can sometimes make knowledge workers appear negative, or worse cynical, particularly when focused on rights such as gender, race or class.

The knowledge worker in service of the crafts needs to maintain a critical space where preconceptions can be scrutinised and, if necessary, replaced. This is similar to a mechanic who needs to take a car out of use and put it “on the blocks”. We need to venture beyond our “bubble”. Makers should not see this as betraying the values of the crafts. It is a dirty business, but someone needs to do it. Craft should be all the stronger as a result.

The path ahead

During its journey thus far, Garland has provided a platform for around 500 thinkers and makers across the wider world. Many of them feel that craft is undervalued by comparison with more abstract pursuits, such as visual arts and design. While lacking power in isolation, there is potential to develop the craft voice by building a platform for sharing this knowledge work. Such a platform draws on the important intellectual work produced in the West, but it must also engage with the heritage and contemporary challenges in the East and South. This cross-cultural dialogue makes it a particularly dynamic time for craft thinking.

You can learn more about our future plans here. Do contact us if you’d like to help with its development.

I’ve been working in the crafts for 30 years now. I am continually impressed by the dedication and generosity of those who make beautiful objects with their hands, skill and imagination. I value a world that enables people to invest their one life in making the most out of what our finite world provides. It is a gift for which I feel eternally indebted.

Comments

An inspiring and thought provoking article that I will be re-reading many times. I had not thought of knowledge workers in the crafts space before even though I now know I have been, in some ways, taking steps in that direction.

Now I have better concepts and context for these efforts.

And I do agree that craft has suffered somewhat from some absence of narrative for modern times. What an intriguing problem!

Thanks

Helen