Photographs of papercuts being produced in Yuxian in 2005. This form of papercutting emerged during the Ming Dynasty when xuan paper was “perfected” and nationally distributed. It is produced in Anhui province using brittle rice straw fibre combined with the inner bark of the hardwood blue sandalwood.

At a time of lockdown, Pamela See finds that Chinese papercutting can flourish by adopting the Taoist ideal of wu wei, doing nothing, in response to the apparent threat of new technologies.

In the days between the first reported death from COVID-19 virus in Wuhan and the closure of the city borders, papermakers at the Xuan Paper Cultural Park in the neighbouring province of Anhui continued a tradition that emerged during the Tang Dynasty (430-930 CE)

The process of sheet forming involved two practitioners dipping a mould with a “bamboo curtain” inlay into a vat of blue sandalwood and rice straw pulp. The entry into the water is at a sharp twenty-five-degree angle from the left side. It is drawn out, with a gentle rocking motion, on the right. The mould is dipped back into the water momentarily from the right at sixty degrees. There is a precisely orchestrated flick to ensure the fibres are evenly distributed.

It is, much like many aspects of papermaking, a perfect illustration of the principle of Wu Wei. Although 無爲 literally translates into “not doing”, “[not] going in advance of things” may be a clearer interpretation. The notion manifests in Chapter 37 of Lao Tzu’s the Tao te Ching:

Tao invariably does nothing, And yet there is nothing left undone. If kings and princes can preserve it, All things will submit to them spontaneously. (After their) submission if any desires occur, I should subdue them with the nameless simplicity. The nameless simplicity is nothing but eradication of desires. Eradication of desires will lead to quietude, Thus the world will naturally find its equilibrium.

The document was written during the Zhou Dynasty (1046-256 BCE), at a time when a precursive form of paper was created using “cocoon waddings.” By the first historical account of papercutting during the Western Han Dynasty (206CE – 9CE), paper was fashioned from hemp fibre. The fifth Emperor, for whom the portrait of a decease concubine had been cut, had an obsession with “bodily immortality”. A nascent form of Taoism offered him a vehicle. By its establishment as a “state” religion during the Tang Dynasty, papercutting, in the agricultural region near the Yellow River, had become established into the form we recognise today.

The revival of bamboo papermaking was necessitated by a need of a supply as opposed to an interest in cultural heritage preservation. Subsequently the process was partially mechanised. The introduction of ‘Naginata’ style Hollanders cut the soaking of bamboo in lime down from three months to one. It also removed some of the processes documented by Song Yingxing in the seventeenth century. Reproduced from 明•宋應星, “天工開物,” Internet Archive, 17 April, 2010, accessed 27 February, 2020

The area, of which Shaanxi Province is central, is the cradle from which both paper and its cutting emerged. At the Cai Lun Paper Cultural Museum, where the inventor of modern pulp strained paper was laid to rest, the cultivation of mulberry bark into the substrate is still practised. The long fibres produce an exceptionally strong paper that can be folded without damage. Referred to as “living fossils”, the papercutting in Shaanxi Province is “well preserved” in style. Synonymous with tradition, its distinctive marks are heavily appropriated. However, it the tools that belie their mimicry in other provinces. On 9 May 2019 in Beijing Magazine it was written of Ansai Papercutting, which is endemic to Shaanxi Province:

The fundamental difference between papercutting in Ansai and other places lies in the scissors… Ansai papercutting does not need craft knives or other tools. A pair of scissors is enough to cut out the most complicated and elaborate patterns.

In Cai Lun’s province of birth, Hunan, paper continues to be made from bamboo. The first account of the fibre’s application in papermaking was in the ninth century Tang Kuo Shi Pu, by Li Chao, followed by mentions in Su Yijian’s treatise on papermaking, Wen Gang Si Pu, during the tenth-century and the seminal Tian Gong Kai Wu written by Song Yingxing during the seventeenth-century. Originating from Guangdong Province, bamboo paper became prevalent during the second half of the Tang Dynasty when supplies of Rattan had become exhausted.

In Cai Lun’s province of birth, Hunan, paper continues to be made from bamboo. The first account of the fibre’s application in papermaking was in the ninth century Tang Kuo Shi Pu, by Li Chao, followed by mentions in Su Yijian’s treatise on papermaking, Wen Gang Si Pu, during the tenth-century and the seminal Tian Gong Kai Wu written by Song Yingxing during the seventeenth-century. Originating from Guangdong Province, bamboo paper became prevalent during the second half of the Tang Dynasty when supplies of Rattan had become exhausted.

Laopeng Village in Hunan is located in an area close to Zhangziajie affectionally referred to as “The Sea of Bamboo.” In late 2019, its outward appearance as a papermaking town was obscured by the damming of the prerequisite source of flowing clean water. Motorised equipment, including a version of Hollander beaters, are in place of the river. After the Opium War (1839–42), handmade papermaking declined with the introduction of mechanised production using woodchip from Europe. However, a shortage of materials created by the incursion and subsequent occupation by the Japanese in the 1930s–1940s initiated a return to handmade papermaking methods. The original localised traditions had developed in response to the abundance of specific forms of vegetation.

Reviving bamboo paper making was an early initiative of the People’s Republic of China. Unlike the culture that catalysed this reactivation, which focused on maintaining traditions, the Chinese were motivated by the need to meet demand. Subsequently, a hybrid of mechanical maceration and hand sheet forming was applied.

Bamboo paper production became prevalent during the late Tang Dynasty. It declined due to the introduction of western pulped-wood methods of paper production during the Qing Dynasty but was revived by the PRC to meet a shortfall in supplies cause by the Anti-Japanese War (c. 1931 – 1945). The photograph of bamboo paper being dried on the grass in Laopeng Village in Hunan demonstrate the papers short and stiff fibres.

At Laopeng, the relatively short-fibred and brittle bamboo paper was dried on the grass as opposed to the walls as depicted in Tian Gong Kai Wu. Amongst its applications is joss paper. Papercutting traditions, which played a similar role in ancestral worship, developed in accordance with the nature of the substrate. Unable to be folded, knives were applied. The multiple blade shapes and sizes engaged in Foshan papercutting, which is endemic to Guangzhou, is a primary example.

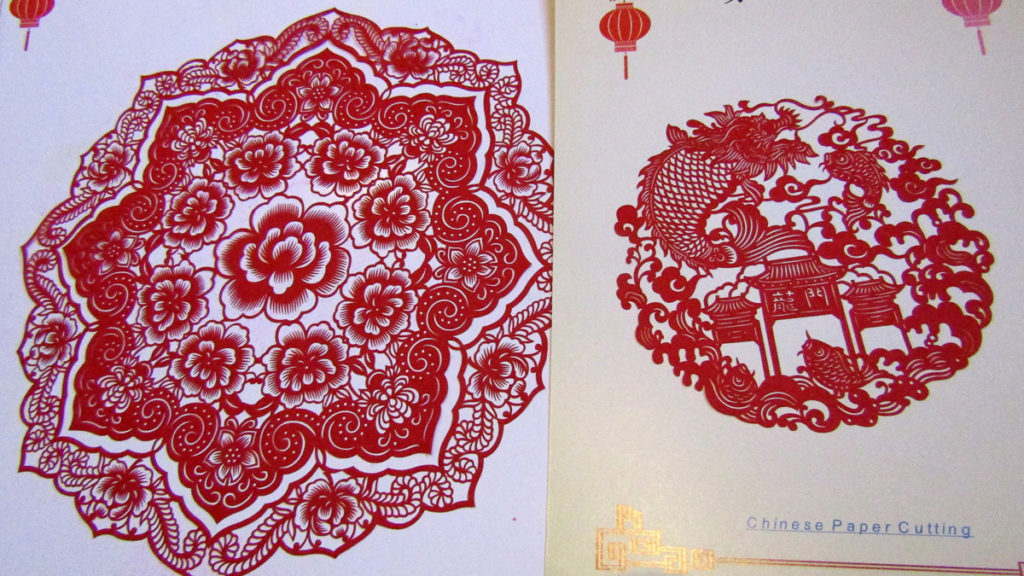

The “Yu” County papercutting in Yuxian presents an interesting example of Wu Wei. Xuan paper, a mixture of long and short fibres, is the favoured substrate for the festively dyed papercuts that are “carved” using knives. Although not endemic to Hebei Province, Xuan paper was “perfected” and broadly distributed during the Ming Dynasty. Both the aforementioned papercutting style and 年画 emerged during this time period.

In early 2020, Hebei Province continued to provide a locus for democratisation through technological development. Seven years ago, The China Daily published an interview with a “renowned” papercutter from the region, Zhou Shuying, in which she urged her colleagues to “stay close to what their ancestors have left for them in the face of technology”.

Lasercut xuan paper could be found In the absence of papercutting mills in the principal papercutting precinct of Yuxian, which is referred to as “Chinese Papercutting Street”. It is, however, not uncommon to find a hybrid of analogue and digital papercuts designed and produced by the same papercutter.

In 2010, the PRC designated the principal papercutting precinct in Yuxian “Chinese Papercutting Street”. However, a decade onward the mills Zhou sought to preserve were notably absent. The locale is occupied by a combination of street stalls offering computer numerical control (CNC) plastic cutouts and stores lined with lasercut Xuan paper cutouts. In both Hebei and Shaanxi provinces, it was not uncommon to find stores selling a combination of handcut papercuts and more modestly priced lasercut versions designed and/or produced by the same practitioners.

“[not] going in advance of things”, it would appear that the intervention of CNC did not cause the decline in papercutting traditions Zhou had predicted. It created market differentiation. This hybridity echoed the observations of Alessandro Ludovico in his book Post-digital Print: The Mutation of Publishing Since 1894 published in 2012:

…not only did the paperless office fail to happen, but the production and use of paper, both personal and work-related, and generally speaking the printed medium, have actually increased in volume.

This diversification extended across the border from Hebei Province into Shanxi Province, where the Guangling Papercutting Museum displayed examples unprecedented both in scale and level of sophistication. The styles of papercutting included appropriation of Chinese woodblock, Chinese calligraphic painting and European impressionist landscape.

In uncanny synchronicity with the late 1960s–1980s emergence of digitalism, the focus of the collection was a series of portraits which appeared to draw its aesthetics from both Andy Warhol and Chuck Close. Each composition was constructed with over thirty hand painted and cut layers of Xuan paper.

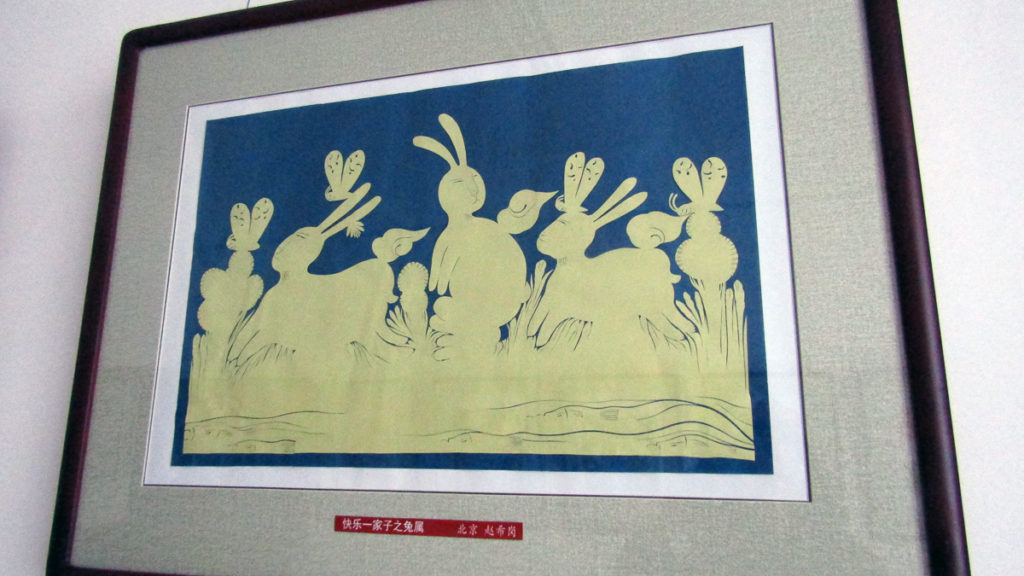

Both the Guangling Papercutting Museum in Shanxi and the Huaxia Papercutting Museum (above) in Hunan exhibited a broad diversity of contemporary papercuts which could not be categorised into regionally-specific styles. This may, from a visual anthropological context, demonstrate a shift in the perceptions of the practitioners. They may no longer identify with the papercutting communities specified the UNESCO List of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. Whereas the Guanglin Papercutting Museum provides vocational training, including in digital design, the Huaxia Papercutting Museum primarily endorses non-digital techniques. The practitioners affiliated with the latter institution are also, by and large, non-vocational.

The Guangling Papercutting Museum is also renowned for the “vocational training school”, which taught digital methods of design in addition to “pure handcrafts.” “Equilibrium,” in a Taoist context, may be found in the first Chinese paper cutting museum in Changsha. The Huaxia Papercutting Museum opened in 2000, proceeding its northern counterpart by seven years. With a focus on preserving ethnographic diversity, the collection of over ten thousand papercuts includes examples the sixty-two papercutting styles recognised by the Chinese Government and UNESCO between 2006-2009. It also includes examples that appear contemporary, in style, from modernism to the cultural revolution. However, the emphasis in Hunan is strictly non-digital. The papercutters, by and large, are also non-vocational.

The principle of Wu Wei may be applied to the present adherence by residents to the PRC recommendations for self-isolation: an entire country “doing nothing”, “and yet, there is nothing left undone.” That there are many pages left in the development of this most resilient and pragmatic of cultures is epitomised by its papermaking. The ingenuity and adaptability which will see the country through this difficult period is also evident in its papercutting.

Further reading

Barrett, Timothy. Japanese Papermaking : Traditions, Tools, and Techniques. New York: Weatherhill, 1983.

China Global Television Network. “Guangling Paper-Cutting Wins Recognition Worldwide.” China Daily. 24 November, 2017. Accessed 8 February, 2020.

Hao, Cui. “Papercutting in Ansai.” Beijing 5, no. 19 (2019): 52-55.

Huang, Yu-Chun. “The Origin, Classification and Evolution of Chinese Paper Cutting.” University of Leeds, 2014.

Hylton, Wil S. “The Mysterious Metamorphosis of Chuck Close.” The New York Times Magazine. 13 July, 2016. Accessed 2 February, 2020.

Jiang, Hang. “The Chinese Art of Papercutting.” 24 August 2016. Youlin Magazine, 24 August, 2016, accessed 19 November, 2018, https://www.youlinmagazine.com/story/chinese-paper-cutting/NjUx.

Kurlansky, Mark. Paper : Paging through History. Thorndike Press Large Print Non-Fiction. Large print edition. ed. Farmington Hills, Mich: Thorndike Press, a part of Gale, Cengage Learning, 2016.

Lu, Yongxiang. A History of Chinese Science and Technology Volume 2. Berlin: Springer, 2014.

Ludovico, Alessandro. Post-Digital Print: The Mutation of Publishing since 1894. Santa Monica: Ram Publications & Distrubutions Inc., 2013.

Needham, J, and T. Tsuen-Hsuin. Science and Civilisation in China: Volume 5, Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 1, Paper and Printing. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, 1985.

Ren, Jiyu. The Book of Lao Zi. 1st ed. Beijing: Foreign Language Press, 1993.

Yingxing, Song. Heavenly Creations. Los Angeles: Hard Press Editions, 2016.

Tsien, Tsuen-Hsuin. “Raw Materials for Old Papermaking in China.” Journal of the American Oriental Society 93, no. 4 (1973): 510-19.

Tzu, Huai Nan, Evan Morgan and John Calvin Ferguson. Tao, the Great Luminant: Essays from Huai Nan Tzu. New York: Paragon Book Reprint Corp, 1969.

Zhe, Tang. “Paper-Cut Artists Strive to Rise above Technology.” China Daily. 7 August, 2013. Accessed 20 November, 2018.

中国古代造纸史渊源. 三秦出版社, 2001.

黄卓鹏 和 胡琳. “华夏剪纸博物馆新馆试开馆 市民可免费参观.”望城区融媒体中心 . 28 August, 2019. Accessed 8 February, 2020.