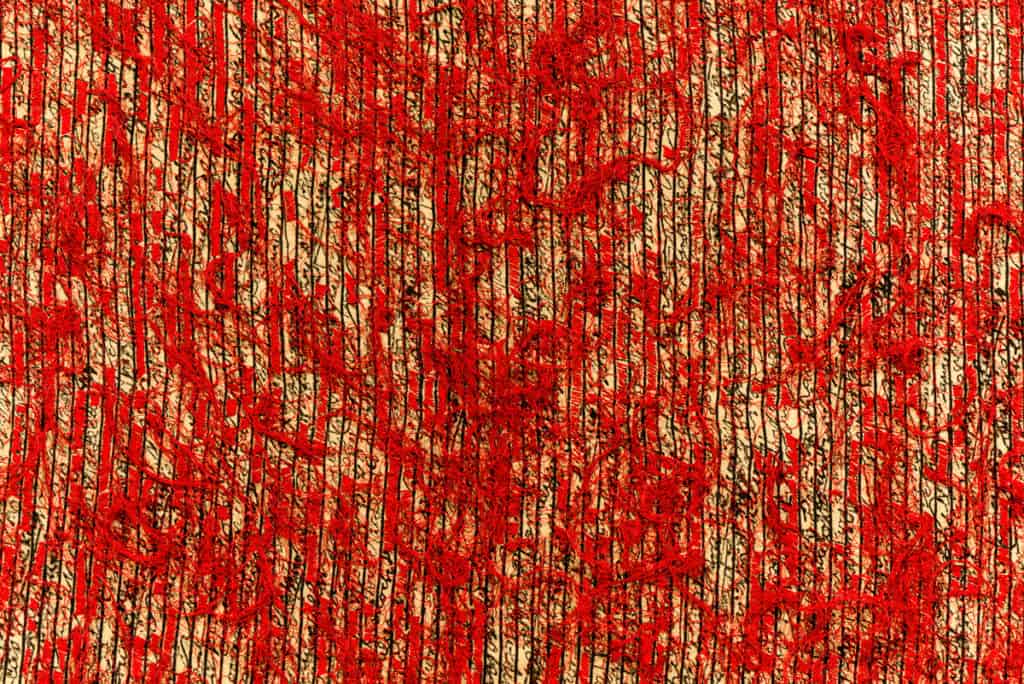

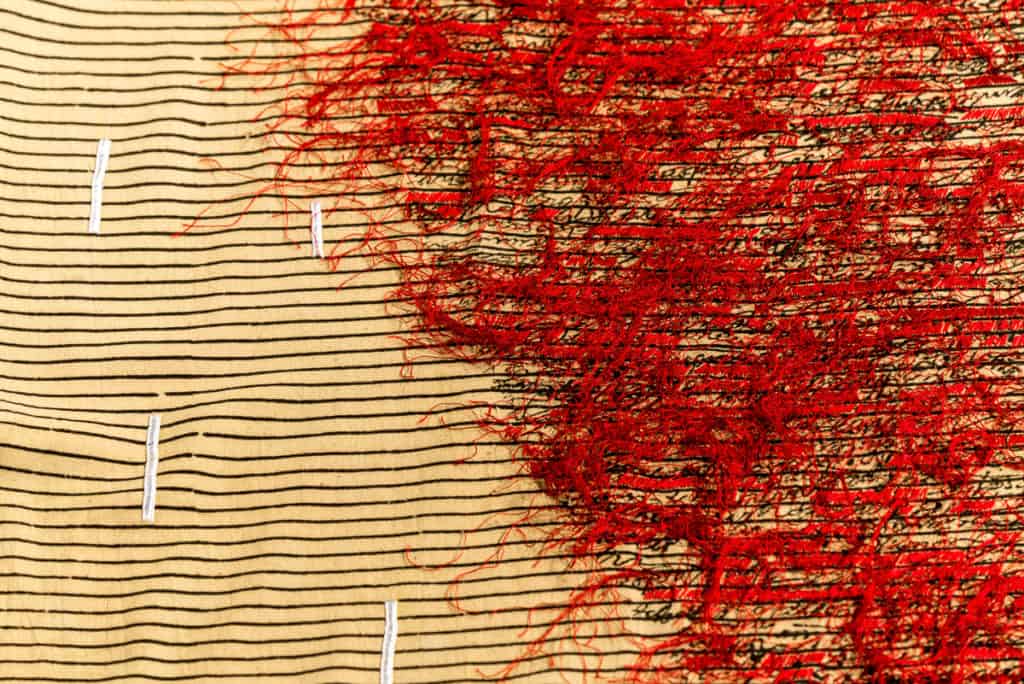

Maggie Baxter, Burst, 2019 (details), direct block print with mineral dye on handwoven cotton, hand stitch, cotton backing. 242.5 x 113cm; photo Neela Kapadia and Ajit Patel; stitching by Gangaba

Maggie Baxter shares new works that use embroidery to evoke the textures of time she has found in India.

Sometimes it is hard to pinpoint exactly where a body of work begins. In my conscious mind Blurred Lines started life in Udaipur in 2015. Amongst the jumble of tourist bric-a-brac leading to the palace there was a shop selling notebooks and journals. In one corner sat a pile of slightly decaying old ledger books with browned paper and hardened, disintegrating leather covers. Their contents were mysteriously incoherent, at least to me. I loved the elusive unintelligibility, of having no entrée to understanding the marks on the page; it was what I needed to kick start new work.

Or was it? I have been working with script, real and imagined, overprinting to create a sense of scribble, scrawl and graffiti since 2004. I also own up to a slightly odd obsession with heavily textured, paint flaking, pockmarked walls. During a recent studio move I came across some long forgotten black and white photographs of peeling walls and graffiti that I had done as a student back in 1980—or even a little earlier. Some things just don’t change.

How to translate such preoccupations into textiles? Block printing, which I treat as large scale, instinctive drawings provides a necessary initial looseness. The print can disappear into deliberate disorder and texture by printing one or several blocks over and over.

In 2016/17 I was part of a group exhibition Serendipitous Happenstance at OED Gallery in Kochi and exhibited The Poetics of Nothing. The three large works are composed formally within an ellipse with arrangements of the same block nuanced through diverse densities of overprinting. The block design, randomly taken from a visitor’s book, has no meaning. In two of the works, running stitch with loose ends, as Paul Klee said “move about freely without goal”. In the third, embroidered diamonds, also a full stop in Islamic calligraphy, float aimlessly over the surface.

This group is the immediate precursor to Blurred Lines. The ellipse, defined by new permutations of blocks, appears in seven of the fifteen textile works. All works are overlaid with various iterations of stitch from the finest Kutchi embroidery to deliberately uneven scrawls and scratches in thread, loose ends dangling.

Never into decoration, or “prettiness”, I have been hauled into the challenge of embroidery through my long association with the Shrujan Trust. Ari embroidery, with its delicate chain stitch, can only be used for illustrative motifs. This is in direct opposition to my preferred non-representational mark making, yet strangely I am attracted to it and have puzzled for years over how to exploit it. In this collection I have used Ari to introduce recognisable words and slightly menacing phrases. The perfection of stitch is a deliberate contrast to the blurred block print. A slightly obscure book Bitten by Witch Fever: Wallpaper and Arsenic in the Victorian Home provided some background imagery and sentences that I have paraphrased; other works indirectly and very loosely reference European medieval manuscripts or out of context colloquialisms. Small drawings hark back to the peeling walls and tattered ledgers.

Maggie Baxter

June 2019

I remember observing Maggie at work in an artisan’s home in Bhujodi, Kutch, earlier this year. A woman from the Sodha community squatted on the floor with a length of off-white cotton, hand-block-printed with iron-black cursive letters—of signatures in English randomly culled from a visitors book; the fabric spilling out in front, rippling like an estuary, over-covering the matting she sat upon. Seated to her right, upon an aluminium manji, made of polyester niwar, head in her hands and bent forward, Baxter’s gaze intently on Gangaba threading her needle, drawing it through the fabric, embroidering designate parts of one of her scrolls, while the production coordinator, Sandhya Jadeja passed on Maggie’s instructions in Kutchi. She was probably thinking of where next from the printed text. Would she like the white yarn in Pakko to be raised, to use black or red filaments and how many loose ends to leave? Whereas I watched the process contemplating the complex modus of collaborating across cultures and syllables, traversing the geographical distance, and most of all, contending with what must inevitably get lost in translation.

Gopika Nath

Burst

Maggie Baxter, Burst, 2019 (details), direct block print with mineral dye on handwoven cotton, hand stitch, cotton backing. 242.5 x 113cm; photo Neela Kapadia and Ajit Patel; stitching by Gangaba

“I had already been working with the idea of using the loose threads as a layer of ‘drawing’ and with Burst, I wanted to see if this could be taken to a level of being almost 3D. I gave Shrujan a sample of the stitching and then the embroidery artisan took over. The white Pakko embroidery on block printed lines that are like an old-fashioned school book, balances this intense centre but does not compete. The centre of the work now looks like an eruption.” Maggie Baxter

This exhibition is on show at Project 88, Mumbai, 8 August – 7 September 2019.