Now bloody wars are emerging around the world, we need to find ways to bring people together, rather than inflame division.

One of our laurels is a Ukrainian now living in Israel. How does it feel to have left a bloody invasion to be now living with another war? I sent her an email asking for her perspective. Sveta Dorosheva responded with a stream of words expressing the utter tragedy of war:

War is always rivers of blood and mountains of corpses, always, no exclusion – that’s why it’s called “war”. Not “threat”, not “disagreement”, not “squabble”, it’s war. And wars don’t take any other form, they are always just the ugly bloody horrible death of many many many people – it’s a terrifying, but a very simple phenomenon, always the same way, just the deadliest death, not a single exclusion, ever. No variation. You can “resolve an argument” or “deter a threat” but never just “stop a war”. There’s no undo button to starting a war. It stops only after rivers of blood and heaps of corpses, because that’s what war is. That’s what was started and now happens.

We witness in horror the scenes that appear on our screens and march in solidarity down our safe city streets. It’s hard to truly understand the ugliness of war for those who are directly affected. But resist it we must, by whatever means.

“Make love, not war” was a popular slogan of protest during the Vietnam War. It presumed that peace could be achieved through a sexual revolution. The idea was that free love would undermine the patriarchal repression that feeds the hunger for war. Today this slogan looks idealistic and unable to match the brutality of conflict.

“Make love, not war” was a popular slogan of protest during the Vietnam War. It presumed that peace could be achieved through a sexual revolution. The idea was that free love would undermine the patriarchal repression that feeds the hunger for war. Today this slogan looks idealistic and unable to match the brutality of conflict.

Pope Francis used his Christmas blessing, Urbi Et Orbi, to describe the real-world interests behind war: “How can we even speak of peace, when arms production, sales, and trade are on the rise?” At $2.1 trillion, current military expenditure far exceeds what is necessary for dealing with climate change and global poverty.

We are more worldly now. “Make love, not war” is a sign of what Hegel called the “beautiful soul”, which “…in order to preserve the purity of its heart, it flees from contact with the actual world.” In today’s speak, we’d describe it as “internal virtue signalling”.

So what can we call for that doesn’t inflame one side against the other? On the Garland platform, we often use the similar phrase, “Make stories, not war”. Nice, but how is this different from the ’60s hippie mantra?

Hopefully, it’s more pragmatic. Story-making is a tangible activity that demands creative expression. As Yuval Harari argues in Sapiens, stories are what make us human. They help us sustain connections across great distances of time and space.

War machines operate at a different level. They work according to calculation and brute force. War breaks rather than makes connections. As Stalin famously said, “If only one man dies of hunger, that is a tragedy. If millions die, that’s only statistics.” As we’ve seen with the dramatic story of Israeli hostages who’ve returned from Gaza, the particular person creates a story that connects in a way that numbers cannot.

The rise of computing has generated a quantitative world that is blind to the particular. As the German philosopher Byung-Chul Han writes, “Capitalism lacks narrativity. It does not narrate anything; it merely counts.”

War is a zero-sum game. An institution like UNESCO emerged after the catastrophe of World War Two to build peace through cooperation in preserving culture. Seeing another culture’s stories celebrated can inspire us to do similar. This is very much the principle behind our Garden of Stories.

In global politics, soft diplomacy is seen as an alternative way of demonstrating national power. One of the tragedies of the invasion of Ukraine is how it tainted Russian cultural icons, particularly its literary greats. It’s impossible to read Tolstoy now without thinking of the savagery his culture has proven capable of. Anastasia Edel writes about this terrible bind:

How should we think about the 23-27 million Soviet citizens who died in the twentieth century’s war against fascism? Many of them were the grandparents of the twenty-first century’s own fascists.

Far better to assert Russia’s greatness by extending its network of Pushkin Institutes than rolling tanks into a neighbouring country.

The power of culture endures beyond war. Take the case of Iran, seen as a potential agent of a future conflict. In the thirteenth century, Iran suffered one of the most brutal invasions in human history. The Mongols killed up to 15 million people. Yet despite this, the Mongol rulers adopted much of Persian culture over time, especially literature and art, leading to its flowering in the Mughul empire.

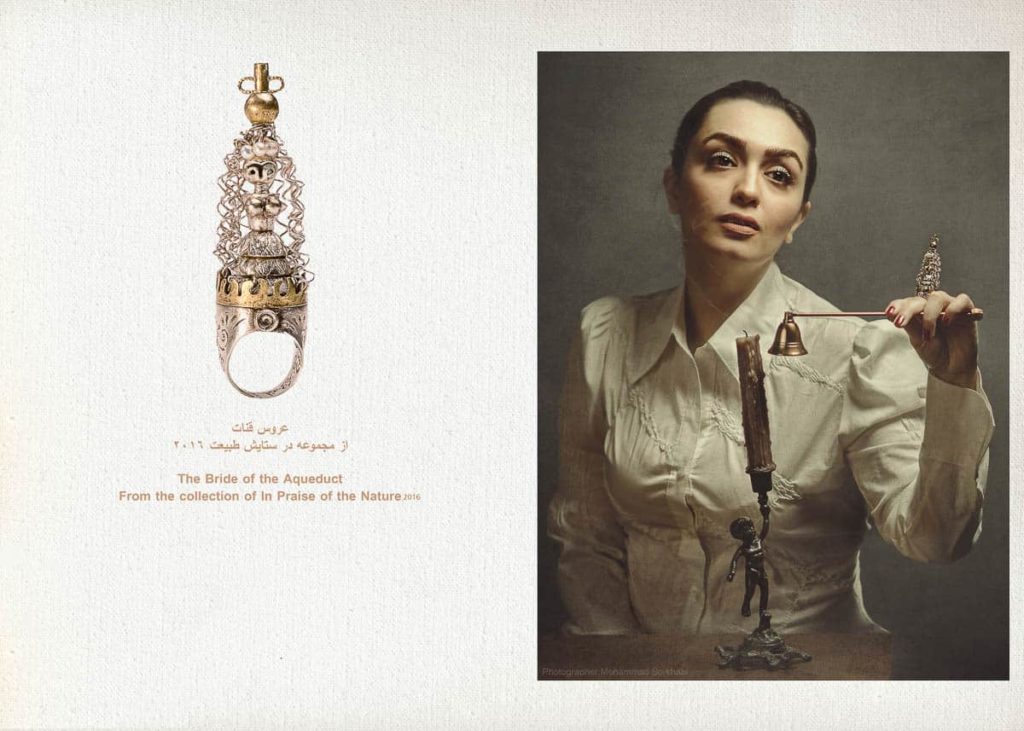

We also see the positive power of stories within Iran. Many of the stories shared in Garland feature young makers who excavate layers of Persian history to find stories they can identify with. For instance, Baharak Omidfar features stories in her work of Sepandarmaz and the Bride of the Aqueduct. This is the message of “Persian prospect”: the contribution that an Iranian renaissance might have to the wider world.

Of course, some stories foment conflict, such as the “Make My Country Great Again” told by populist leaders in Russia and the USA. As Tyson Yunkaporta writes in his latest book, Right Story, Wrong Story, we need stories that reflect the complex web that connects us together, rather than conspiracy theories of the evil other.

Make stories, not war. Stories will not stop the killing fields once the war has started, but they will hopefully make us think twice before turning on the war machine.

Sveta recounts the story of her grandfather, who shared family meals with enslaved German soldiers after the world, despite famine and the protest of his wife. After seeing Germany’s help in the current war, her grandmother was incredulous, “Germans are saving the Jews from Russians..? Maybe he was on to something.”

Sveta has the last word: “There’s a tiny hope that humanity wins.”

On the Other Hand is an exclusive article for Garland Circle members.