- Stole, 1828, made of Bengal muslin with Dresden embroidery (Tapash Paul, Drik Photographs)

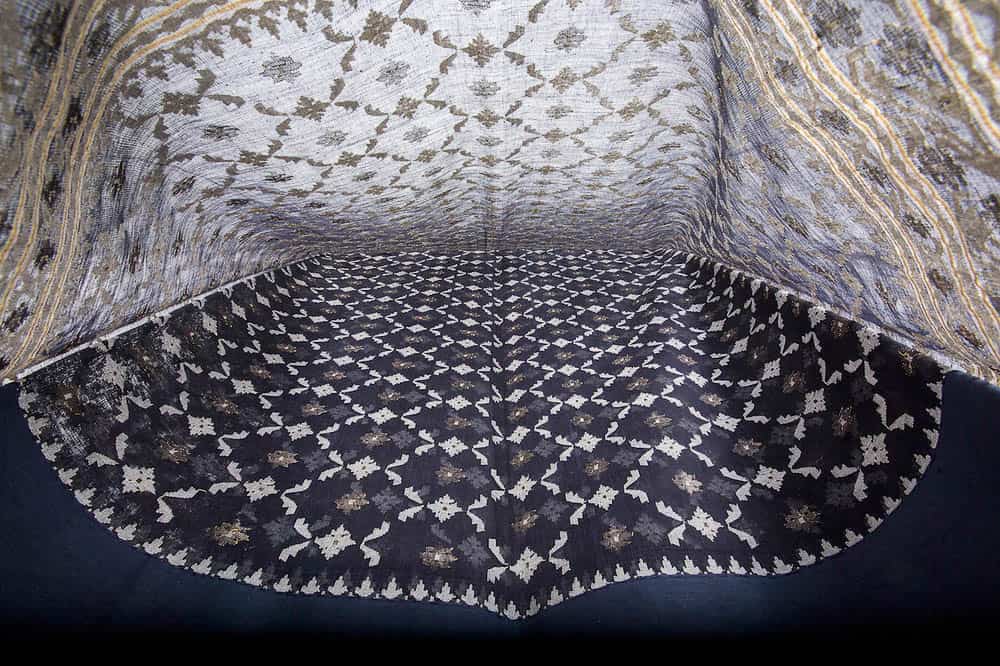

- Jamdani sari, 20th century, the only surviving variety of muslin that uses coarser threads with traditional motifs, as woven by master-weaver Haji Kafiluddin of Rupganj, Dhaka, photo: Shahidul Alam, Drik Photographs

- Angarkha, 19th century male dress, made of Bengal muslin, photo: Shahidul Alam, Drik Photographs

‘The cloth is like the light vapours of dawn’, Yuan Chwang [Chinese traveller visiting India, 629—645 ct]

Muslin was the attire of kings and queens, a fabled fabric which was the pinnacle of European fashion in the 18th and 19th century. Originally called ‘mul-mul’, it was named by Marco Polo after the large cotton trade through the town of Mosul in Iraq. Rare, delicate and fine, described as ‘woven air’ muslin was the most sought after textile and at its height had reached all corners of the globe.

During the 2nd and 3rd century India’s fine cotton was well known as ‘Gangetic Muslin’ treated as a tribute, handed over from one royalty to another, forging friendships and cementing alliances. With the Muslim conquest of Bengal in the 12th century, trade and specifically textiles received a large boost. After the arrival of the Portuguese in late 15th century, a small amount of Indian textiles started to travel directly to Europe, which rapidly increased after the Dutch and the British joined in the Indian Ocean trade from early 17th century. Muslin travelled the earth bringing prosperity to its traders, specially the East India Company, 75% of whose wealth would at one time come from this single item. In the 18th century Bengal’s textiles had grown from 16% to 55% of the EIC trade and India was contributing an astonishing 25% of the world economy and England less than 2%. But muslin’s industry was extinguished by a system of exploitative regulations brought in by the British rulers and a wave of new technology where the domestic cotton industry was replaced by their machine made fabrics. By 1880, the luster of Bengal’s muslin had faded and muslin was allowed to die.

Today muslin’s unique cotton plant, the phuti karpas which grew on the banks of the Meghna and its tributaries, is believed to be extinct. The unique yarn is not spun and the weaving techniques used on jamdani (a last surviving variety of muslin) are all that is left of our lost art, even though coarser threads are used now than the fine ones of the past. Sadly, there are few credible records on muslin by Bangladeshis or any appropriate samples of its finery in our national museums. Its story is written by outsiders and the best examples of its historic products are kept in museums abroad.

Over the past two years, Saiful Islam, CEO, Drik led a project team from Drik which extensively researched the topic with the assistance of curators, weavers and artisans both internationally and at home. Drik is an internationally reputed multimedia organisation based in Dhaka, Bangladesh. The project’s (www.bengalmuslin.com) goal was to retell muslin’s story from the viewpoint of the craftspeople and to inspire the revival of a new-age muslin. Multiple events were held and an international book was also published. Below is an extract from the book, Muslin. Our Story (available on Amazon or contact islam.saif25@gmail.com to get your copy shipped out, USD $60.00 less shipping).

Below is an extract from the book, Muslin. Our Story.

Muslin – The Magic and the Mystery

Muslin – what magic does the name hold? What mystery lies behind the filaments of this fabric? Who wove it? Who wore it? To look upon it today is to look upon a discarded rag, off white, slightly awry, studded with floral patterns in many cases, plain or at best a golden edging. Did the ‘fool and his lady fair’ fall for the hallucinatory spin of the wooden wheel, the monotonous shuttle of the hand loom or get swept off their feet in a medieval designer’s hysteria? Was this the start of the ‘wannabe’ culture that continues with the Diors of today?

Clothing in some form, texture and pattern has been with us for centuries. Textiles have been spun, embroidered, shaped and draped across the shoulders of common people and royalty in every culture. We all know that more intricate designs have been printed or spun into the body of a cloth, grander tapestries have hung, richer silk has been spun. After all, muslin was simply cotton, fine and fragile which most Mughals discarded after a day’s wear, diaphanous and see through (the Emperor Aurangzeb chiding his daughter for wearing see through, while she actually wore seven layers), providing neither strong shelter from the weather nor an effective barrier to unwanted gazes. Tedious to make and almost impossible to hold, a full dress was beyond a measurable weight, the final product rare and only fit for supreme leisure and little else.

Perhaps herein lies its allure, the arachnidan pattern, the interwoven threads providing little else but an illusion of protection, a feeling against the skin, the perpetual caress of cloth, like ‘a second skin, the skin of the moon’ said the Farsi poet…its reality was an illusion in texture. While wearing jamdani (translated as flowers in a container), the master weaver’s goal was to ensure that the flora would appear to float, to trick the eye into beholding a design held across the body by the beauty of its wearer and subsume the skill of its maker, to carry the beloved garden of the Mughals around oneself like a scent without a source, for the audience to discover a third dimension before 3D was officially discovered.

Was this the unheralded bearer of female emancipation, daring that courtly gossip be fuelled while the power and the glory remained on her side? To hold it, gaze upon it, is to be transported into a timeless past, where the sheen of antiquity on the soft cloth is heightened by a luminescent after-glow. Lighter than a lover’s sigh, softer than a butterfly’s wings, in its transparent simplicity lay its subtle pull upon the imagination of poets and the pockets of those who could afford it.

If the threads could speak, would they reveal to us more than we care to know. Would we feel guilty that the cloth which had protected us from the elements was not itself protected from the elements in the end? How many wars did it provoke? How many deaths did it determine? How many poems did it ink? How many loves did it inspire? What was the weight of the greed that it added to the misery of its makers?

We can only conjecture in the back of our minds and imagine the early morning whirring of the spindle, the late night slide of the shuttle, the dip of the needle, gaze through its transparency … and wonder at the wonder of it all.

Saiful Islam is CEO of Drik, a Bangladeshi multimedia company that challenges social inequality. Muslin. Our Story will soon be available on Amazon (or contact islam.saif25@gmail.com to get your copy shipped out, USD $60.00 plus shipping). See also bengal.muslin.com.