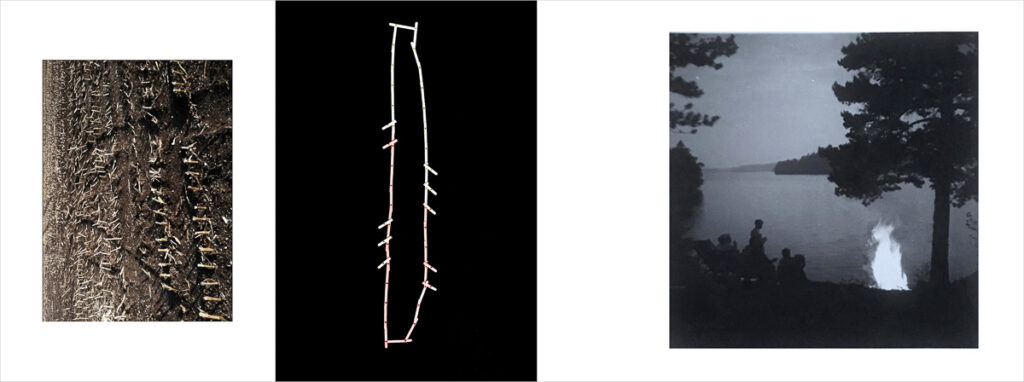

Inari Kiuru: Necklaces from Seven sacrifices of flowers from New Spring, Old Gods series (2020-21). Photo: Inari Kiuru

Inari Kiuru shares the Finnish cultural roots that ground her work, reflecting an enchantment of nature.

New Spring, Old Gods series of jewellery and images (2020 onwards) investigates my Finnish roots and a strong ancestral kinship through the act of making from what is available, together with old Finnish nature-centred beliefs and customs. This article is the first tentative, intuitive (and by no means comprehensive) exploration of these connections–a freeform prelude to further work, research and discovery.

(A message to the reader in Finnish.)

(A message to the reader in English.)

Adapted and expanded from material for IIb, presented during Radiant Pavilion 4-12 September 2021, the original text and images were first published in ordinari observations and in Instagram @ordinari_observer,

Inari Kiuru: White nights, come dancing! from New Spring, Old Gods series (2020). Photo: Inari Kiuru

The birth of the series and finding an ancestral connection

While making the first necklaces for New Spring, Old Gods during last winter’s covid-19 lockdowns, vivid memories from childhood and teenage years spent in nature flooded my waking hours and dreams. Through the recollections and the physical fabrication of the pieces, I sensed a palpable connection to, even a spiritual presence, of my mother, godmother, grandmothers and great grandmothers, many of whom were makers (especially of hand-spun, woven and naturally dyed textiles), and a long line of craftspeople behind them. This coming together has been a beautiful, unexpected gift, especially comforting and empowering during the pandemic isolation.

The jewellery pieces shown here honour this heritage and Finnish traditions dating back thousands of years. In my artist statement for Schmuck 2021 jewellery exhibition I describe making the first necklaces for the series:

“ … at home in Melbourne, during a long covid-19 lockdown while unable to access my studio, tools or the usual materials. The pieces are fabricated entirely from hundreds of plastic jewellery price tags I’ve accumulated, using only their own locking mechanisms for construction.

As I sorted the tags into sizes and colours, becoming familiar with the ways they bend and behave, I soon forgot the small pieces were industrial plastic and I myself a contemporary artist. Instead, as the first patterns developed into more experimental designs, resembling natural forms, I became simply one in a long and ancient chain of craftspeople who’ve used gathered, seasonally available materials to create.

While working, I strongly sensed my Finnish roots deep in nature, and the forms grew evocative of our pre-Christian spring rites and ornaments connected with death, rebirth, the forest and the Sun, depicting delicate details of plants and flowers that return to life after a long winter.”

Some old Finnish nature-centred traditions and design background to the pieces

In the ancient Finnish belief system and mythology, everything emerges from nature and everything returns to nature. The seen and the unseen, including our ancestors and spirits inhabiting natural places, are equally respected.

For most contemporary Finns, there’s no separation between nature and daily life, either. Everyday activities naturally follow the rhythm of the seasons, and people’s personal connection to a natural landscape remains strong since the wilderness is rarely further than a fifteen-minute drive or train trip away, even from the capital city. I’ve come to realise that I, a migrant, still carry this sense of belonging to a greater, organic whole too, having instinctively adjusted my existence in suburban Melbourne to have a seasonal resonance.

The traditions, myths and rituals I write about here are well known to Finns: fresh, beyond the pages of history books, and still actively incorporated into seasonal festivities. In recent years, there’s also been a strong revival of Finnish cultural heritage, resulting in old customs, holy places and sung poetry actively practised, protected and researched again, especially by younger Finns.

Taivaannaula, a contemporary organisation preserving and cultivating ancient Finnish customs as a part of this revival, accurately describes Finnish native spirituality as “ … traditional beliefs, customs and celebrations which are connected to our ancient worldview and the yearly cycle of nature. Officially, Finland has been a Christian country for over a millennium. Yet many [Finnish] later beliefs, customs and attributes towards nature reflect deeper and far older nature-based worldviews. This ethnic tradition which has its roots in Uralic…religions, has sometimes survived almost to the present day.” (Taivaannaula, 2021)

Wildflowers as talismans, offerings and ingredients of spells

Wildflowers have always been an essential part of the Finnish spring and summer celebrations, and have a strong connection to rituals and dreams in our folk magic. Delicate in structure and appearing as hundreds of colourful species from the southern coast to the northernmost Lapland, native flowers are especially precious due to the very brief seasonal window of new growth on our latitudes.

In Finnish pre-Christian traditions, flowers were gathered from meadows and forests and used as talismans to protect cattle and people from mischievous or evil spirits. Together with food (the Finnish sacrificial traditions didn’t include animals), they were also included in offerings, performed around dedicated holy trees and sacred groves called ‘hiisi’. In these old customs, the flowers were woven into garlands and wreaths.

Wildflowers have also been an important ingredient in spells, especially in ones sealing or revealing one’s romantic future. These have traditionally been cast on Summer Solstice, coinciding with Midsummer festivities and the light-filled, “white nights” of late June when the sun doesn’t set.

Gathering seven kinds of different flowers, gazing into reflective water or placing the posey under one’s pillow, in anticipation of seeing a future sweetheart, is a ritual still well and alive in Finland (some questions are obviously timeless!). Executed in complete silence, for words will break the spell, these practices sometimes involve walking backwards or around a dedicated landmark such as a well while reciting certain words, and are completed as the last thing before going to sleep.

It was a late summer’s afternoon, golden orange and deep blue, so familiar from my early memories

And, as love binds us to people, so it deeply connects us with the land we grow up on. One night, while making this series, I woke up crying. In the preceding dream, I was a child, back in my hometown, left on a patch of grass (perhaps a small park) while my parents had gone to get something. It was a late summer’s afternoon, golden orange and deep blue, so familiar from my early memories. I lay down as I waited, inspecting the blades of grass and the tiny blossoms growing amongst them, feeling them against my cheek. Then an overwhelming sadness arose in me, with the thought “I will never see the flowers of my homeland again”. I’ve rarely felt such deep grief as in this dream.

- Inari Kiuru: The Rite from New Spring, Old Gods series (2020), plastic price tags, 350 x 40 mm. Photo: Inari Kiuru

- Inari Kiuru: Seven sacrifices of flowers, 2020, seven separate necklaces which make one larger piece, plastic price tags, 500 x 15 mm. Photo: Inari Kiuru

- The Rite and Vaari (my maternal grandfather, “Vaari” means grandpa in Finnish) wearing a traditional summer flower garland and wreath, c. 1990, Nurmes, Eastern Finland. Extended caption: My Vaari Toivo Timonen was a man who lived for a century and farmed the same land for nearly 80 years. He also fought in two wars. Vaari kept daily notes of rains and temperatures; worked with the lunar cycles, and cultivated a deep knowledge of plants, flowers, different natural energies and the way of the forest. In this picture Vaari is wearing a traditonal summer wreath and a garland, made by my sisters and I, sitting on the old steps of the farmhouse on a summer’s afternoon.

- Inari Kiuru: Seven sacrifices of flowers, 2020, seven separate necklaces together, plastic price tags, 500 x 15 mm. Photo: Inari Kiuru

Spring, Midsummer and Winter Fires

Seasonal bonfires are an ancient pagan European custom, continuing as a living Finnish tradition. They are burned in late March around the Spring Equinox; in late June around the Summer Solstice, and sometimes in midwinter during the Winter Solstice. The original purpose of the high flames was to ward off evil spirits, believed to become restless while the Sun reached its peak positions in the sky. The fires in late March also helped with preparing for a fertile soil and were sometimes burned on the fields, as well as were believed to encourage a bountiful harvest in the autumn.

Spring bonfires are still lit on the west coast of Finland, now as a social community event, and the Midsummer fires (kokko in Finnish) in most areas of the country. Traditionally, and understandably especially during a dry summer, they’re burnt by a body of water. The old winter fires have now been replaced with candles and elaborate seasonal lighting designs adorning buildings and urban areas during December, the darkest of the winter months.

- Inari Kiuru: Sometimes cruel, the April sun, 2020, plastic price tags, 200 x 2 mm. Photo: Inari Kiuru, landscape photo: Laura Kiuru

- Inari Kiuru: Field, 2020, plastic price tags, 400 x 2 mm. Photo: Inari Kiuru. The image of the bonfire c. 1955, Lohja Island, Southern Finland, by Vilho Kiuru.

Forests, wild harvests and the king

An important tradition, common throughout northern Europe since ancient times and written in the Finnish modern-day constitution, is everyone’s “freedom to roam” the land, and the right to gather natural produce from the forests. Come August and September, berries and mushrooms are one of the most abundant seasonal wild harvests: important to Finns now; having made up a great part of the autumn’s and winter’s nutrition in the past generations’ diets, and most certainly included in the sacrificial gifts to nature spirits and gods in our pantheistic traditions up until the 1800s (and even later).

The king of the forest and the ruler of its offerings, revered and feared, is the bear (karhu in Finnish). The most sacred animal in Finnish mythology and pre-Christian spirituality, the powerful bear is ever-present. Only a few days ago, a friend reported she’d seen one while on a local day hike in Eastern Finland. It also lives on in the modern Finnish language. We have multiple words which mean “bear”, but are expressed in a roundabout way, so the king could be safely mentioned without provoking him. These circumlocutions include Otso, Ohto, Tapio (which is also one of the names of my father and my son), Kontio, Nalle and Mesikämmen. Mesikämmen is translated as ‘honey-paw’ or ‘mead-paw’ in the poems of our national epic Kalevala.

Throughout my childhood and teens, during the days of late summer and early autumn, our family (just like everyone else) spent a great deal of time gathering edible plants in the forest. Our jams, cordials, desserts and many dishes for the winter months, prepared from frozen goods stored in our enormous chest freezer, required collecting bucketfuls of blueberries, cloudberries, lingonberries and chanterelles over many weekends.

One of my earliest memories is being carried in a baby-harness on my dad’s back as my parents were foraging for mushrooms. As dad wandered on among the pines and fir trees, I remember noticing how my little blue gumboot slowly slipped off my foot, fell, and quietly vanished into the soft undergrowth. I was so young I couldn’t speak yet … so I remained silent. The shoe was never found.

- Inari Kiuru: Illustrations based on Finnish customs and mythology for New Spring, Old Gods, 2021, digital media. The Finnish national epic, Kalevala (compiled and arranged into a story by Elias Lönnrot in the mid 1800s, from gathered song-poems recited from one generation to another), preserves a version of the Finnish creation myth in a beautiful way. According to the story, the universe was made from seven eggs of a waterbird, laid on the lap of a crying, pregnant goddess. Six golden eggs and one of iron fell into the first sea and broke, and their pieces formed the land, sky, sun, stars and the clouds.

- Inari Kiuru: Flames, 2021 and While the butterflies still sleep, 2020, plastic price tags, 400 x 1.5 mm and 420 x 3 mm. Photos: Inari Kiuru

One version of the Finnish creation myth tells us the universe was made from seven eggs of a waterbird, laid on the lap of a crying, pregnant goddess. Six golden eggs and one of iron fell into the first sea and broke, and their pieces formed the land, sky, sun, stars and clouds. Our national epic, Kalevala (compiled and arranged into a story by Elias Lönnrot in the 1800s, from gathered song-poems recited from one generation to another), preserves this story in a beautiful way.

A postscript

The relationship between Finnish elements and the pieces in New Spring, Old Gods is spontaneous and sensual, stemming mostly from my personal experiences, early memories and inherited knowledge and folk wisdom, rather than any specific historical details. While this approach is consistent with my vision for the body of work as a contemporary, subjective interpretation of a national heritage, I will also, as the next step, deepen my formal research into our early customs and their context within other early nature-centred spiritual traditions. The current revival of Finnish paganism and the resulting emerging documentation will also offer an interesting, comparative stream of information.

The early jewellery works in the series are all woven from the same material, industrial plastic tags, dictated by the pandemic lockdown circumstances, as are the accompanying digital images composed at home. I’m drawn to experiment with a wider range of ingredients, exploring both 3D and 2D realms, when allowed to return to the studio environment again, and look forward to discovering how the formal language of the series will develop as our freedoms return.

Two of the original neckpieces shown here, Seven sacrifices of flowers and White nights, come dancing! (both 2020) will be exhibited in March 2022 in Schmuck, Munich, Germany. A series of five necklaces from the series was also selected for the current Contemporary Wearables ‘21 exhibition in Toowoomba Regional Art Gallery. Some of the pieces featured in this article were originally made for II, an exhibition alongside Michaela Pegum planned for September 2021 but now postponed to March-April 2022.

Photographs and images: ©Inari Kiuru 2021, unless otherwise credited within the text. Inquiries: Funaki.

Further reading

The Kalevala. I recommend looking up the English translation listed below of The Kalevala, the Finnish national epic, as well as reading the article regarding the 1999 illustrated edition.

Kalevala. Lönnrot, Elias (compiler), Väisänen Hannu (illustrator), 1999, Otava, Helsinki.

Hannu Väisänen: Recreating The Kalevala. Books from Finland, 1999 <http://neba.finlit.fi/booksfromfinland/bff/299/hannuv.htm#> The artist Hannu Väisänen, who has illustrated a new edition of the Kalevala, describes his approach to the epic.

Kalevala: Epic of the Finnish People. Lönnrot, Elias (compiler), Eino Friberg (considered the best translator of this work), George C. Schoolfield (ed), Otava Publishing Company, Helsinki, 1988. First published in Finland 1835.

Karhun Kansa (“People of the Bear”) Karhun Kansa is a contemporary religious group, officially recognised by the State of Finland, cultivating indigenous Finnish spiritual traditions. This site offers information about the yearly festivals and feasts celebrated according to ancient Finnish beliefs.

Taivaannaula Information about Finnish customs and traditional seasonal celebrations by a contemporary organisation preserving and actively cultivating these.

The work of Uno Harva (Finland 1882-1949) on Finno-Ugric and Altaic religions and shamanism. Some of his writing has been translated into English.

About Inari Kiuru

Inari Kiuru is a Finnish-born multidisciplinary artist and graphic designer with Honours degrees in Fine Art and Visual Communication. She works and lives in Melbourne, continuing to investigate her native relationship with changing seasons through works observing light, clouds and atmospheres in urban environments. Known for her use of non-precious materials such as concrete and steel, and having begun many of her projects through photography and walking documented at inarikiuru.blogspot.com, the core of Inari’s practice is revealing beauty within ordinary, everyday things. Inari is represented by Funaki, and some of her work can be seen at galleryfunaki.com.au, in her blog, and in Instagram via @ordinari_observer and @the_indoor_forest_project.

Inari Kiuru is a Finnish-born multidisciplinary artist and graphic designer with Honours degrees in Fine Art and Visual Communication. She works and lives in Melbourne, continuing to investigate her native relationship with changing seasons through works observing light, clouds and atmospheres in urban environments. Known for her use of non-precious materials such as concrete and steel, and having begun many of her projects through photography and walking documented at inarikiuru.blogspot.com, the core of Inari’s practice is revealing beauty within ordinary, everyday things. Inari is represented by Funaki, and some of her work can be seen at galleryfunaki.com.au, in her blog, and in Instagram via @ordinari_observer and @the_indoor_forest_project.

Comments

Most interesting article providing an excellent insight into Finnish culture