“Amnesiacs that we are, we believe that they adored the god or goddess sculpted in stone or wood. No: they were giving to the thing itself, marble or bronze, the power of speech, by conferring on it the appearance of a human body endowed with a voice.”

Michel Serres, The Natural Contract, University of Michigan 1995

As humans, we often depend on inanimate objects to establish our sense of identity, a fact often categorically stated not just by anthropologists but endorsed by philosophers as well. However, such a notion would be incomplete if we did not acknowledge the power of objects to speak to us. A simple questioning of the object like “what does it do?” assigns a power to a particular artifact, tool or everyday article which imbues it further with meaning, purpose, perhaps even intention. The characteristics of a ceramic vessel, a wooden ornament or even a simple metal spoon sets the tone for dictating human interpretation and action. It prompts us to interact with it through a range of sensory experiences placing an obligation on us in ways through which we relate to the object or other people via its specific form and nature.

In fact, artifacts can form a world of their own, independent of human intentions as Gell (1998) notes. In many instances, abstract thoughts and mental representations can be manifested in the shape of objects, rather than the other way around, where thoughts may pre-empt the form of the objects themselves. Hence, objects may set up stylistic universes of their own where we, as humans may merely find our roles as makers and users fitting into a predetermined schema of thought, actions and existences.

A close encounter with Masooma Syed’s work titled The Sword deceives the viewer in the first instance that it is a glorious historical artifact. Encased lovingly in a red silk casket, it evokes feelings of royalty, preciousness and power. Upon unpacking the object further, it reveals a narrative of dictatorial practices in an increasingly male-dominated country with a brutal colonial past. The ornamental handle, originally a metal buckle from a masculine waist belt, sports a menacing blade of luscious long locks, the length of a woman’s braid. Cleaned, washed and combed, its warrior spirit is authoritative yet submissive.

Culturally an embodiment of a woman’s glory and dignity, more strands of human hair come together in a poetic installation. Delicate deer galloping and battling in a migratory struggle accompany a verse from Mir, a seventeenth-century Muslim poet.

Breathe here softly as with fragility here all is fraught,

In this workshop of the world where wares of glass are wrought.

Mir Taqi Mir

Henna stained and golden brown lengths of hair, bleached by the harsh sun, are shaped into dainty forms to weave a tale of the “brittleness and resilience of human life”. Manifesting itself through the deer, the hair becomes a metaphor for the uncharted wilderness and the quest for liberation in a journey of chance. In Syed’s signature carefree style, through a tracing and caressing of the strokes of ancient cave paintings, a bare wall transforms into a magical Disneyland.

Syed, a visual artist and painter by training has often crossed over to the domain of jewellery and body adornment through her various interactions with traditional metal craftsmen, goldsmiths and gemstone setters. Her approach to incorporating organic and discarded materials like human hair, nail clippings and milk teeth with silver or found objects is “intuitive and playful rather than analytical” (artist statement). Notions of rebellion and resistance, often breaking the boundaries of personal space, enter a fiery socio-political arena to create a grim narrative of displaced intimacy and vulnerability.

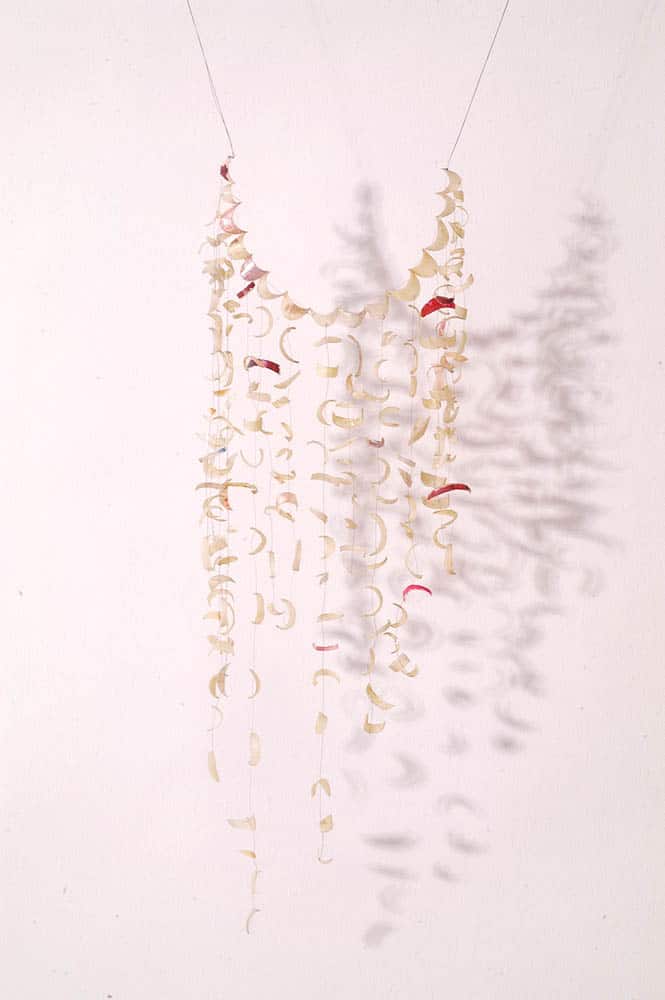

The transient nature of Syed’s work is a carefully articulated and delicately balanced contrast of beauty and revulsion. Almost weightless and colourless, For you is a bouquet of flowers made entirely of human nail clippings. A blunt commentary on the fragility of human emotions, it is both absurd and spontaneous at once. More nail clippings, some manicured, some shaped and polished, while yet others neglected and untouched form a garland in Your Majesty. Gleaming and translucent like pearls, they take the form of an intricately strung neckpiece. A dark humorous take on the colonial history of Syed’s homeland, this elaborate “crown jewel” dangles precariously on strings of human hair.

- Masooma Syed, Your majesty, 2013 human nails and human hair , 6cm x18cm

- Masooma Syed, ‘The Crown, 2015, human hair, 8cm x 8cm

- Masooma Syed, To life, human hair, 2013, 2cm x 24cm x 15cm

In an ode to the weary culmination of a long, but endless journey, Syed’s own hair takes the form of her feet in To Life. Ethereal wisps of hair intertwine in a shadowy solemn web that “touch the earth and bear the weight of the entire body” (artist statement). Coming together in an almost spontaneous extension, The Crown is a meticulously shaped and stitched version of the artist’s mother’s hair into a light and graceful crown fit for a queen. The feet, in stark contrast, speak of a soul with a heavy heart.

Across the spectrum from these intimate discarded body “components” lie Affan Baghpati’s redundant, rejected and re-appropriated domestic objects. Brass betel nut crackers and spoons, rare finds from vessel makers and antique homeware bazaars have been dusted off, polished and crafted into hybrid treasures for reconsideration. Utensils representing a myriad of domestic practices in the traditional South Asian household become amulets in a desperate bid to protect oneself from the consequences of an abrupt end to a bygone era—a time of plentiful bounties, refined aesthetics, good taste and a charmed life.

Ceremonial and lovingly crafted, a series of brass spoons perform with pastry wheels in an intriguing, convoluted deathly dance of mortality. The smooth rounded contoured spoons sync their steps cautiously around the menacing scalloped edges of their counterparts in an unlikely, doomed courtship. The stout bull and the proud horse appear and disappear as ghostly negative and positive afterimages, their primary purpose being to entertain the crowd as the grim mourning procession passes through the streets of time.

In Baghpati’s work, titled The Hunt on Betel Nut Cracker—Sarota, he uses an embellished brass nutcracker, an item used by the first generation of migrants making their journey across the border from India to Pakistan post-1947, a consequence of the War of Independence. Ironically, this was also the last generation to use this unique object, characterised best as the orchestra director in the traditional paan ritual. The art of making and dressing the paan, or Indian betel leaf with carefully cut areca nuts, desiccated coconut, candy-coloured sugar-coated aniseed, silver-leafed cardamom pods and other exotic condiments was the epitome of high culture and common practice in Muhajir households.

A galloping deer innocently enters this carefully orchestrated ceremony, only to be ambushed by a panther, an attempt on the part of the craftsman to appease the Gods. The deer, a victim of sacrificial offering, becomes a vehicle for seeking refuge from a looming catastrophic cloud of economic turmoil in an allegorical representation of the deeply embedded religious and cultural beliefs in South Asia.

- Affan Baghpati, The Hunt on Betel Nutcracker, 2015, brass, copper, 5.5cm x 15cm x 0.8cm

- Affan Baghpati, The Hunt on Betel Nutcracker, 2015, brass, copper, 5.5cm x 15cm x 0.8cm

With an artistic practice encompassing several overlapping disciplines like taxidermy, sculpture and miniature painting, Baghpati’s relocation to the city of Lahore to pursue a postgraduate degree prompted a shifting of scale in his work due to space constraints. The jewellery studio happened to offer some tempting options in that context when he decided to enrol in an elective course in fundamental jewellery making. Previously exploring juxtapositions with discarded furniture and metal artifacts, Baghpati started to translate his ideas into smaller but more detailed objects. The stencil-like silhouettes are a demonstration of his skills acquired from the study and practice of miniature painting.

- Affan Baghpati, Horns on Kettle, 2016, horns, copper, varying dimensions

- Affan Baghpati, Horn on patila, 2016, horns, copper, varying dimensions

As Baghpati repositions and manipulates complex forms by forging, sawing and fusing cutlery and functional homewares gleaned from antique utensil wholesalers in Peetal Gali (literally translated as “Brass alley”, a legendary maze-like bazaar in Karachi), a fictional history begins to unravel. Thus ensues a negotiation between the artist’s aesthetics, the object’s aesthetics and the traditional aesthetics of the region, all three weighed down with promises to fulfil certain expectations in the South Asian gharana (household). Together, these elements prompt a closer examination of an ongoing debate concerning objects and the overt display of desirability, beauty and eroticism pervading the arts and aesthetics of the region.

From here on, we become witnesses to a blurry battle, a desperate scuffle to pick up the scattered pieces in a divided homeland with an uncertain future even after seventy years of independence. The historical and personal narratives being grappled with may be similar, secretly alluding to more than what the eye may see, revealing scars that map tales of displacement and decay. The discomfort some viewers experience upon encountering such objects may be more about their lack of understanding of the cultural aesthetics as they come to terms with the challenges or affirmations provoked through the underlying brutally honest juxtapositions. If objects, precious or otherwise are to co-exist as meaningful companions in our society, it may be of utmost importance that we respect their silence and listen closely to their whisperings. For without a deep consideration and acceptance of the core aesthetic and cultural values, an object’s reification, even within its own kind will remain incomplete, pulling tautly at the symbiotic relationship between the artist and his creation, the maker, the user and society at large to bring the dialogue to what may prove to be an abrupt and unhappy end.