- Bees in blossom of river red gum, Northern Victoria

- Lorraine Connelly-Northey, Possum skin cloak Mooloomoon Lagoon, Medium: Rusted gauze, springs, iron and tie wire, 2015

- Lorraine Connelly-Northey, Possum skin cloak rafting for fresh water mussels on country, Medium: Rusted rabbit-proof netting wire, iron, tie wire and fresh water mussel shells, Wangaratta Art Gallery Collection, 2015

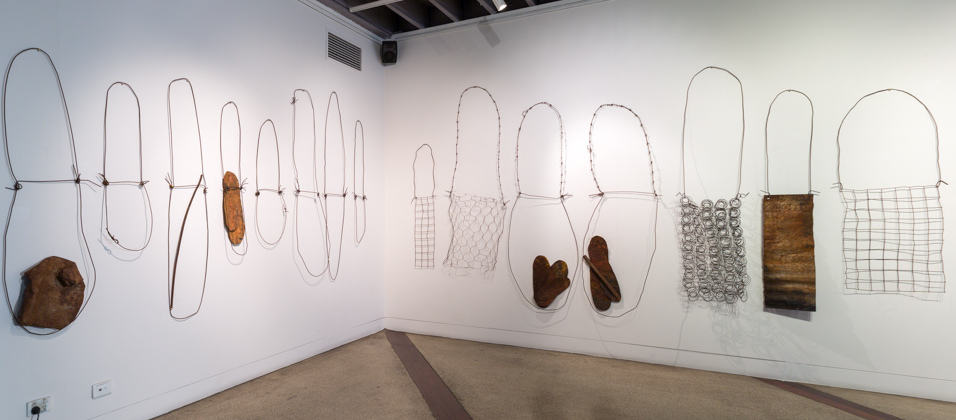

- Lorraine Connelly-Northey, ‘Ground Drawing with Found Materials’ (installation detail), 2015, cast offs, corrugated iron, bed springs and fencing wire. Photographer: James Henry. Courtesy of the Koorie Heritage Trust

- Lorraine Connelly-Northey, ‘Ground Drawing with Found Materials’ (installation detail), 2015, cast offs, corrugated iron, bed springs and fencing wire. Photographer: James Henry. Courtesy of the Koorie Heritage Trust

- Lorraine Connelly-Northey, ‘Ground Drawing with Found Materials’ (installation detail), 2015, cast offs, corrugated iron, bed springs and fencing wire. Photographer: James Henry. Courtesy of the Koorie Heritage Trust

Melbourne artist Penny Algar and Lorraine Connelly-Northey have had many conversations over some six years about the importance of Australian flora to Aboriginal peoples especially those species endemic to the Riverine and Mallee regions near Swan Hill. These have led the artists to start research towards an exhibition dealing with the River Red Gum and other plants of aboriginal usage in which Connelly-Northey will be the lead artist. The cultural stories recounted here are typical of Lorraine’s generosity, mindfulness and thoroughness, characteristics also of her art. This article is based on a question-answer exchange between them.

Throughout Aboriginal Australia, plants are signifiers of shelter, warmth, food, healing and ceremony. Woven through the work of the highly respected artist Lorraine Connelly-Northey, a Waradjerie (Waradjuri), Wongibong (Wongaibong) woman is a deep acknowledgement of her rich mixed cultural heritage. The Mallee flora and the ecology of the Riverine region especially the Murray River have had a powerful influence on her prodigious output.

Geologically Australia is ancient with nutrient-poor shallow soils and a varying climate – yet these are factors contributing to it being one of the planet’s most botanically biodiverse continents. Tragically for conservation, the majority of Australians neither understand or value the native flora. Since white settlement introduced European flora, they have been dominant and aesthetically preferred in public and private.

An early mentor inspiring Lorraine’s 25 years of research into Aboriginal peoples’ relationship to and uses for the native flora was Jill Pattenden, now a retired Swan Hill teacher and passionate advocate for Aboriginal peoples’ culture and wellbeing, and a close family friend.

Connelly-Northey, who has conducted many of her own horticultural experiments with native plants in her parent’s backyard; is especially interested in the potential of various plant materials for weaving within her own work – the range of colours, textures and pliability. She germinates, grows, and presses plants herself from ripe seed she collects in summer. Her own ongoing personal botanical archive comprises many of these plant specimens.

She first learnt from her father, who had always lived on the land, about the complex local ecology: distinguishing native plants from introduced species; and learning which plants were used by Aboriginal peoples and for what purpose. Both plant stories and the life suggested by abandoned farm materials such as fencing wire or tin found in the many tip sites they visited on their journeys together; have become ingeniously incorporated into Lorraine’s art today.

Connelly-Northey’s uncanny ability to create beautiful simple, minimal forms – almost always by hand – is distinctive. In a similar way to her forebears who took only from the plants what was necessary, so they would grow and reproduce the following year. Lorraine does not use native plant material itself in her work as she feels her ecological understanding is not yet complete. Respectful of the sustainable gathering of materials in order to ensure their ongoing health and reproduction. She does not want to further deplete the wild stock.

Pattenden introduced Connelly-Northey to another significant mentor, the ethno-botanist Dr Beth Gott, who impressed immensely with her knowledge of plant usage but also for naming plants using the correct Aboriginal words. For example, the common water reed, Bull Rush is called Kumbungi. Lorraine Connelly- Northey gives credit to Gott’s outstanding research. Dr Beth Gott, is now in her nineties and an honorary research fellow at Melbourne’s Monash University. As Lorraine says, Gott’s marvellous work in linking science (botany) and Indigenous Australian culture has led to a greater understanding of the intricate and long history of the relationships between plants and humans in this country. These include the use of plant material for food, medicine, fibre, implements, dishes, canoes and adhesives-resins and gums.

In Koorie Plants, Koorie People, Dr Beth Gott and Nelly Zola describe the Victorian Eucalyptus species:

No other continent is so emblematically linked to a particular botanical species, a reflection of the fact that there are actually 500 different species of Eucalyptus in Australia, growing in almost every environment. Victoria has 80 species of which the majestic River Red Gum (Eucalyptus camaldulensis) found along every rivers edge, is the most widespread of all.

Lorraine Connelly-Northey likens the River Red Gum to a boarding house – a refuge and a storehouse of much goodness.

To the Aboriginal people the presence of the River Red Gum indicates the availability of fresh water – and lots of it in the wet season when the rains bring floods for the gums to have their annual drink. The timber and bark of the River Red Gum was used to make shelters, canoes, shields, coolamons, and digging sticks for example. Traditionally its timber provided fuel for the long-burning fires that generated warmth and attracted the good spirits while the light from the fire kept the bad spirits at bay. Ovens in the earth were kept lit day and night – often for steaming foods such as kangaroo and yams. Fires were lit in the tree hollows to smoke out the possums, which were eaten, and the pelts used for cloaks. Beds from possum skins were made on the ground, still warm from the buried cooking ovens below. Half the fire could be used to create an oven in the ground to.

As a habitat for visiting birds, they led to the provision of eggs for food. Excretions from the Lerp insect on the leaves is sweet tasting. The leaf litter containing plant material, animal and bird droppings enabled the recycling of nutrients back into the soil below, ensuring replenishment and longevity.

A hollow in the base of a River Red Gum could be used as an instant shelter, otherwise stripping the tree trunk of bark panels allows for the simple construction of a lean-to for shelter. Fire can be created from rubbing together a River Red Gum hardwood firestick and a firestick from a neighbouring softwood tree. The bark and wood are ready fuel for a fire that burns outside the shelter day and night. In daylight heat from the fire was used for making tools and implements – and sometimes to create a naturally sterilised hotplate which cooking seed cakes, witchetty grubs or small lizards to name a few.

With the use of stone axes and wooden wedges bark are prised from the tree trunk from one to 20 metres in length for canoe making, smaller pieces for shields. Burls or gnarls cut from the tree are scraped out and used as storage cavities or to hold water. ‘Bowls of the bush’ – known in Waradgerie language as Coolamons – can be extracted from hollow branches rather than being cut out with wedges and axes. The saplings of the River Red Gum are stripped of their bark to make digging sticks which are used in conjunction with the Coolamon to scoop and dig alternately for food such as Yams and burrowing animals.

The River Red Gum food resources have other uses. For example, before they are cooked possums are first skinned for their pelts for making cloaks. After being cooked goannas have their oil extracted for a body rub against biting insects and no doubt provide a conditioning for the skin when hunting and gathering out in the Australian bush. Then again, the inner bark can be pounded for fibre, and the gum or sap, high in tannin, can be used as an adhesive; and smoked over fire or steamed, the leaves reduce fevers.

The landscape in which the Red Gum thrives has changed dramatically since white settlement. Agriculture, in particular the control of river flows by weirs and locks for irrigation, logging and now climate change have done much to alter the flows of our waterways, not least the mighty Murray River. The River Red Gum is under stress. Many of the old “scar” trees, witnesses to human activities over many centuries, are dying and disappearing. They are not, as Connelly-Northey says, getting a `drink’ often enough.

The artist Lorraine Connelly-Northey is an important artist of our time. We must all `listen’ carefully to the cross-cultural stories that are so generously articulated and shared through the materials and forms of her sculptural practice.

Murray River Cloak

Lorraine Connelly-Northey Murray River Cloak, shown in “Embodied Energy” exhibition at the Counihan Gallery, 2008, 300 x 200 x 50cm, photo: John Brash

Lorraine Connelly-Northey’s work resonated with me from the first piece I saw was one of her beautiful Narbongs (string bag) in an exhibition at the National Gallery of Victoria about eight years ago. I was delighted she accepted an invitation to participate in the Embodied Energy exhibition at the Counihan Gallery in Brunswick which Edwina Bartlem and I were co-curating in 2008. Thus her Murray River Cloak (pictured) was conceived. Again, Lorraine’s work consistently showed deep, respectful affinity with nature – and presented aspects of it – that were never particularly overt. In September 2015, I lent it to the Wangaratta Art Gallery for their solo exhibition – Buwurr-galang , cloaks past and present by Lorraine Connelly-Northey. All works involved manipulating and reimagining modern industrial materials.

Murray River Cloak is a monumental sculptural ‘drawing’ which ‘maps’ the great Murray River, twisting thousands of kilometres through south-eastern Australia from its beginnings in the sphagnum moss peat bogs in the Australian Alps near Mt Kosciusko; through Barmah, the world’s largest River Red Gum forest ; and to slowly empty into the Southern Ocean near the Coorong. The many demands on the Murray Darling catchment’s waters make it an enormous and complex feature of Australian life, biologically and politically. Connelly-Northey is especially interested in the movement of precious life-giving water through the landscape – above ground in streams and rivers or a hidden flow through rock fissures and caves.

As a cloak – floating, ghostily translucent – the piece recalls the traditional animal fur cloaks of southern Aboriginal peoples. And suggesting too the soft, shed skin of a snake, it presents a powerful disembodied space akin to the significance of Indigenous people moving for thousands of years throughout the catchment.

Lorraine commented recently, “You need to have a reason to do everything. I don’t just make work for the sake of it.” She made Murray River Cloak outdoors near the Murray River itself, by weaving rusted, burnt barbed wire and fencing wire from old tip sites, with the rabbit-proof wire netting forming a delicate filigree. Barbed wire is much more difficult to work. It is a potent symbol for Indigenous people of prisons and other sites of exclusion, such as traditional land divided up for farming.

Further reading

Zola, N & Gott, B 1992, Koorie plants, Koorie people: traditional Aboriginal food, fibre and healing plants of Victoria, Koorie Heritage Trust, Melbourne. p. 55.

Kevin Murray Craft Unbound – make the common precious, Craftsman House,

Zola, N & Gott, B 1992, Koorie plants, Koorie people: traditional Aboriginal food, fibre and healing plants of Victoria, Koorie Heritage Trust, Melbourne. its page 55

Grant, S. & Rudder, J. A new Waradjuri Dictionary, Restoration House 2010.

Author

Penny Algar is an artist and curator with a special interest in Australian flora and in particular their cultural importance to the First Peoples of Australia, the Australian Aboriginals. Penny is based in Melbourne but travels frequently to Northern Victoria to a Box Woodland property she shares with her partner. Penny met Lorraine Connelly-Northey in 2008 when she was co-curating (together with Edwina Bartlem) the exhibition “Embodied Energy” in 2008. They have maintained contact and continue a discussion about their shared interest in Australian flora and are currently seeking opportunities for Connelly–Northey to develop and exhibit new work based around the flora of the Victorian Riverine. (The background sculpture detail is from Lorraine Connelly Northey’s “Murray River Cloak” made for the exhibition “Embodied Energy”, in 2008. The work is from the collection of Penny Algar and Michael Spencer.)

Penny Algar is an artist and curator with a special interest in Australian flora and in particular their cultural importance to the First Peoples of Australia, the Australian Aboriginals. Penny is based in Melbourne but travels frequently to Northern Victoria to a Box Woodland property she shares with her partner. Penny met Lorraine Connelly-Northey in 2008 when she was co-curating (together with Edwina Bartlem) the exhibition “Embodied Energy” in 2008. They have maintained contact and continue a discussion about their shared interest in Australian flora and are currently seeking opportunities for Connelly–Northey to develop and exhibit new work based around the flora of the Victorian Riverine. (The background sculpture detail is from Lorraine Connelly Northey’s “Murray River Cloak” made for the exhibition “Embodied Energy”, in 2008. The work is from the collection of Penny Algar and Michael Spencer.)