“Jawun” is a word in the Girramay, Jirrbal and Gulnay languages for a bicornual basket. These languages are spoken in the rainforest region, which incorporates Tully, Murray Upper and Cardwell on the north-east coast of Queensland.

In the white settlement that occurred in the late nineteenth-century, many Jirrbal peoples were rounded up of communities into missions, which led to the decline of traditions such as jawun making. Some baskets were traded for tobacco. One of the avid collectors of jawun was Joseph Campbell, archdeacon and rector at Cairns (1904-9). In 1916, he sold his collection to the Queensland Museum for 30 pounds, where it remains as important record of material culture.

Jawun making was revived in the late twentieth century thanks to the efforts of people like Abe Muriata, whose baskets are a treasured as Australia’s living cultural heritage.

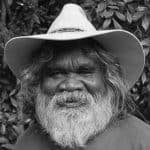

Craftsperson – Abe Muriata

- Abe Muriata collecting lawyer cane, Bilyana, 2012, photo: Valerie Keenan, Girringun Aboriginal Art Centre

- Abe Muriata collecting lawyer cane, Bilyana, 2012, photo: Valerie Keenan, Girringun Aboriginal Art Centre

- Abe Muriata collecting lawyer cane, Bilyana, 2012, photo: Valerie Keenan, Girringun Aboriginal Art Centre

- Abe Muriata collecting lawyer cane, Bilyana, 2012, photo: Valerie Keenan, Girringun Aboriginal Art Centre

- Abe Muriata begins a new Jawun, 2012, photo: Valerie Keenan, Girringun Aboriginal Art Centre

- Abe Muriata heating the cane; photo Valerie Keenan, Girringun Aboriginal Art Centre

- Lawyer cane in various stages of preparation; photo: Valerie Keenan, Girringun Aboriginal Art Centre

- Abe Muriata with the beginnings of a large Jawun

- Abe Muriata with work in progress, photo: Valerie Keenan, Girringun Aboriginal Art Centre

- Jawun by Abe Muriata, photo: Valerie Keenan, Girringun Aboriginal Art Centre

- Abe Muriata with very old Jawun in British Museum collection, 2015, photo: Valerie Keenan, Girringun Aboriginal Art Centre

- Latest Jawun by Abe Muriata; photo: Valerie Keenan, Girringun Aboriginal Art Centre

Abe Muriata grew up in Murray Upper in rainforest country between Cardwell and Tully in North Queensland. In 1996, his community received a delegation from ATSIC (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission). He remembers an attempt to find a gift to offer these important visitors and an embarrassment in the way something had to be thrown together. “I made it my mission to go out and make a really good jawun”, Abe said.

Over 15 years ago Abe set about learning to make jawun. He sought advice from an elder about how to work with lawyer cane, how to treat it with fire and heat and to prepare it for weaving. He also went to the Queensland Museum to carefully study the construction of the older baskets in museum collections. Eventually, through hard work and research he was able to master the craft of jawun making and is arguably the best weaver of the basket in the world. This was vindicated in 2005 when one of his jawun was purchased by the Queensland Art Gallery, and others have since been acquired by the British Museum, the National Gallery of Australia, National Museum of Australia and others.

Abe is involved in every phase of jawun making. He gathers the lawyer cane; “You have to pick the right season to gather the cane. There has to be just the right amount of sap. Then you need to know which section to cut. The section a metre from the ground is good for the structure. Towards the top of the cane is good for weaving.” On the same day it is cut, the cane is treated over an open fire by the creek. The cane still has flexibility while there is sap inside. It is bent into the right shape over the fire. The weaving process itself can happen anywhere—”I work wherever I am”—and takes upwards of four weeks depending on the size. Ceremonial baskets are decorated with coloured ochres using traditional designs.

Part of the pleasure of jawun making for Abe is the connection to an ancient tradition. “To me, it is an object that is a perfect form, it is a perfect engineering design. It is unique. My culture is an ancient culture and you find this jawun nowhere else in the world. Its manifold use as an object such as for food preparation, for food collection, for carrying babies—it is a multi-purpose utility object. It has a visually appealing design, when plain or when decorated. Once it is decorated with traditional colours, with ochres, and traditional design, it becomes a sacred ceremonial gift. People tend to give reverence to the many facets of this unique object and I am privileged to be part of its journey, seeing it almost go from obscurity to something that is more readily recognised and appreciated today.”

“I work with the Girringun Aboriginal Art Centre and my baskets are generally sold through them before they are completed. There are other weavers of jawun, of burrajingal and wungarr (eel traps) which are also made from lawyer cane. They have more recently also been made with other contemporary materials like ceramics, scrap metals and recycled materials. ”

“When I stand and consider the big picture I see in the horizon the future people waiting to embrace the mystique of the culture and the wonder of this object crafted from ancient but wise wisdom. I can see my Aboriginal descendants reaching out and taking hold of this timeless culture. I can see the Museums, the curators, the public seeing the work and looking in wonderment. It is a vision I see.”

“In this modern era, Desley Henry started something that I ran with and I am looking forward to the next person or people who take it up and continue this marvellous tradition.”

Despite its importance, and the huge demand for Abe’s baskets, there are currently less than 20 weavers in the world who are making the baskets.

Back l to r Debra Murray, Daniel Leo, Chris Muriata, Philip Denham, front Emily Murray, Penny Bong, Theresa Beeron, Eileen Tep, Sally Murray GAAC collecting lawyer cane with rangers 2016

Artist

Abe Muriata is a Girramay man of the Cardwell Range area. He is a traditional rainforest shield maker creating large wooden shields painted with traditional ochres and designs as well as with contemporary designs and materials. Such shields were once used for sorting out of disputes and for ceremonial purposes. A self-taught weaver of the lawyer cane jawun, Abe explores different techniques to create finely crafted bicornual baskets unique to the rainforest people. Abe taught himself the weaving technique from watching his grandmother make them when he was a child. He also studies old artefacts in museums created by his ancestors to inspire his individual jawun technique. Abe is also a painter and a potter. He is represented by Girringun Art Centre.

Abe Muriata is a Girramay man of the Cardwell Range area. He is a traditional rainforest shield maker creating large wooden shields painted with traditional ochres and designs as well as with contemporary designs and materials. Such shields were once used for sorting out of disputes and for ceremonial purposes. A self-taught weaver of the lawyer cane jawun, Abe explores different techniques to create finely crafted bicornual baskets unique to the rainforest people. Abe taught himself the weaving technique from watching his grandmother make them when he was a child. He also studies old artefacts in museums created by his ancestors to inspire his individual jawun technique. Abe is also a painter and a potter. He is represented by Girringun Art Centre.

Host – Christine Waterson

- Jawun in context, 2016, photo: Christina Waterson

- Christina Waterson making The Komodo Series during a residency at The State Library of Queensland in 2008. Photography David Sandison

- Plexa#1 (Detail) from The Komodo Series 2008 by Christina Waterson. Photography Aidan Murphy

- Array 2007 (Installation) by Christina Waterson for Australian Institute of Architects Awards Event. Photography Christopher Frederick Jones

- Near Far, 1996 (Detail) by Christina Waterson, photo: Christina Waterson

I’ve always connected with and treasured weaving for its beautiful tactile presence and layering, as well as the myriad of repetitive shadow patterns that weavings create. The large-scale woven collections Near Far 1996, Rest 2002 and The Komodo Series 2008 show my personal exploration of these qualities and continued passion for weaving.

A love of Bi-cornial baskets or jawuns grew while working as the exhibition designer for Story Place: Indigenous Art of Cape York and the Rainforest exhibition at The Queensland Art Gallery in 2003. For this exhibition we worked closely with each of the 300 contemporary and historical art works and cultural objects that included shields, fibre articles, figures, sculptures, ceramics and paintings. The objects that really moved me were the jawuns and their unique form, structure, and strength.

On further research after the Story Place exhibition, I found Abe Muriata to be one of the few male practitioners weaving jawuns. Abe brings exceptional skill, precision and material sensitivity to each of his works. I welcomed one of Abe’s beautiful lawyer cane jawuns into my life in 2005 when a series of Abe’s works were featured in Woven Purpose (artisan, Brisbane).

Waking each day to Abe’s beautiful jawun is a joy. It hangs beside my bed with cherished works by Tim Johnson, Darcy Clarke and Elizabeth Gower. In those first personal morning moments of awakening my eyes often rest on the distinctive form of the jawun—its strata and layering of structure over a multitude of fragile shadows. Abe’s work engages me to look deeper and transports me to a realm of possibilities and creative moments of insight.

Perhaps because of my architectural background I often imagine what it would be like to rest inside the inner curves of the jawun’s enveloping surface or within a special space having the jawun’s beautiful qualities and construction. In making large work with scale in the public realm, I’ve seen first hand a transformation in the way people experience and engage with my work. I would love to experience Abe’s work at this larger scale.

In 2014 I nominated Abe for the Chain Reaction exhibition (artisan) as a practitioner whose work and generous spirit inspire me. During Abe’s stay in Brisbane I invited him to my studio and we spoke about working at a larger public scale. I felt extremely privileged to express in person my deep respect for Abe and daily joy of experiencing his work.

Host

Christina Waterson’s creative practice includes making artworks and large-scale public art commissions; designing exhibitions, events and product collections; and sharing knowledge through blogging, talks and workshops. Trained as an architect, Christina also studied art and design; practicing across these fields before establishing her own studio in 2007. Her experience includes creative roles for organizations such as Howwecreate, Urban Art Projects, and Cox Rayner Architects. She worked extensively as an Exhibition Designer for The Queensland Art Gallery and The Museum of Brisbane. She is a recipient of the Winston Churchill Memorial Trust Traveling Fellowship to research the origins of patterns and their relationship to art, design and architecture.

Christina Waterson’s creative practice includes making artworks and large-scale public art commissions; designing exhibitions, events and product collections; and sharing knowledge through blogging, talks and workshops. Trained as an architect, Christina also studied art and design; practicing across these fields before establishing her own studio in 2007. Her experience includes creative roles for organizations such as Howwecreate, Urban Art Projects, and Cox Rayner Architects. She worked extensively as an Exhibition Designer for The Queensland Art Gallery and The Museum of Brisbane. She is a recipient of the Winston Churchill Memorial Trust Traveling Fellowship to research the origins of patterns and their relationship to art, design and architecture.

Museums

For most people, to see a jawun first-hand it is necessary to go to an Australian museum. Here’s the display from the National Museum of Australia. The jawun is at the centre of the Northern Queensland collection.