Of all the art forms, fibre seems a medium that is most beholden to place. The task is to transform what’s at hand into meaningful objects. The material is not abstract like words or pixels. It hasn’t been processed and shipped from elsewhere like metal or glass. It is rooted in the ground where one lives.

Despite this groundedness, or maybe because of it, fibre art sits low down in the art hierarchy. Basketry is a particularly humble creative practice, associated more with community workshops than solo gallery exhibitions. Yet it persists.

A country like Australia has a remarkable generation of fibre artists, who are largely unheralded. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island artists sustain a tradition thousands of years old. Meanwhile settler artists have adapted northern traditions of making to southern flora.

This is a critical story for a country like Australia, still trying to find its originality in a largely imported culture. It resonates with other colonised lands, seeking to recover an indigenous language of place. But also more broadly, it speaks to the enduring craft challenge of making do—testing one’s capacity to transform fleeting materials into objects of enduring value.

Over a series of seven articles, I will cover a range of fibre practices across the Australian continent. As male whitefella, my capacity to write about what is largely women’s business is limited to that of outside witness, rather than a purveyor of craft secrets. My aim is to understand them in context, eventually proposing a set of critical principles for giving value to this work in its own terms. In case that destination sounds a little academic to you, I do hope you find the journey interesting in itself.

We start in far north Queensland, a tropical region whose high rainfall contributes to dense rainforests. We’re already familiar with the most renowned Queensland basket, the jawun, made from lawyer cane and celebrated today in the work of Abe Muriata. Muriata has been actively promoting this technique both locally and internationally thanks particularly to the Girringun Arts Centre in Cardwell. I visited when they were recovering from the recent CIAF fair. The catalogues that manager Valerie Keenan stacked on my arms were testament to the work they had done, including the recent exhibition in Monaco. I was invited over to meet the chairman at a BBQ for visiting indigenous rangers from Mount Isa. It was a busy scene of camaraderie, reflecting living custodianship of the land.

- Rhonda Brim, Sherry-Ann Brim, Tanya Dutt, Sheila Brim and Rhonda Duffin

- Basket by Sheila Brim from Kuranda

- Rhonda Brim basket

It was a different story north of Cairns. In Kuranda, the local Djabugay culture is proudly led by Mona Mona Elder, Rhonda Brim. Until recent funding cuts, she helped revive the local language in schools. She is also a master weaver who is herself proficient in traditional techniques such as jawun. When I suggested a meeting, she preferred to bring her group of weavers along for an open discussion. We planned to meet at a local park, but due to heavy rain we sought refuge in the pub, which we occupied without ordering any drinks. With me was a Garland intern from India, Tanya Dutt, who thought I could do with a brown person alongside me.

As the conversation progressed, I began to appreciate the challenges they faced. There’s no place in town where the weavers can gather to make and sell their work. There’s no legal entity that could apply for funds to establish one. There’s not even a computer to do email. Where this lack of resources is felt particularly is in the disengagement of the next generation. They said that without a dedicated space, it’s hard to interest children and grandchildren who have their heads in their phones and follow US rapper culture.The mood picked up as we started to talk about plans that could make a difference, but it was hard to see how these could be realised without a platform to build on. Eventually, the Sky Train arrived and the tourist mob wandered into the pub, filling up tables for the counter lunch.

We parted with good intentions, though on a ground of solid realism. It seems ironic that this group is so isolated in a town that has such a regular flow of potential customers. When I asked around the shops if there any local baskets for sale, I began to understand why. In one shop, filled with industrially-made souvenirs, I inquired if they sold local Aboriginal baskets. The saleswoman looked incredulous. She responded rhetorically, out of the corner of her mouth, “Have you seen them on the street?” I said I had just meet with some locals who made beautiful baskets, which would be popular with tourists, but she didn’t seem open to that line of information.

Brim carries a tradition that she received from her grandmother, Wilma Walker, a Kuku Yalanji woman and matriarch of fibre in Mossman Gorge, near Port Douglas. Walker has been influential in passing skills onto an entire generation of artists. Some are more fortunate in the support they receive. Yalanji Arts is a thriving centre at the Gorge, drawing on the strong tourist trade and employment as guides. One of highlights of the 2016 Cairns Indigenous Art Fair were black palm baskets made by a granddaughter, Delissa Walker.

- Delissa Walker wearing the kankan basket in the traditional way.

- Delissa Walker with her kankan

- Delissa Walker in the dilly bag

- Delissa Walker wearing kankan baskets

Wilma passed on her own name, Ngadijina, to Delissa, who has since handed it down to her eldest daughter, who she is teaching to make the basket today. All her baskets at the UMI show were sold, including three to the National Gallery of Victoria and there are orders for more. Though she has mastered the kan kan (black palm basket), there are techniques she still needs to learn, such as making the handles and rims with lawyer cane and bees wax.

- Shannon Brett at the Yarrabah Art Centre

- Philomena Yeatman from Yarrabah

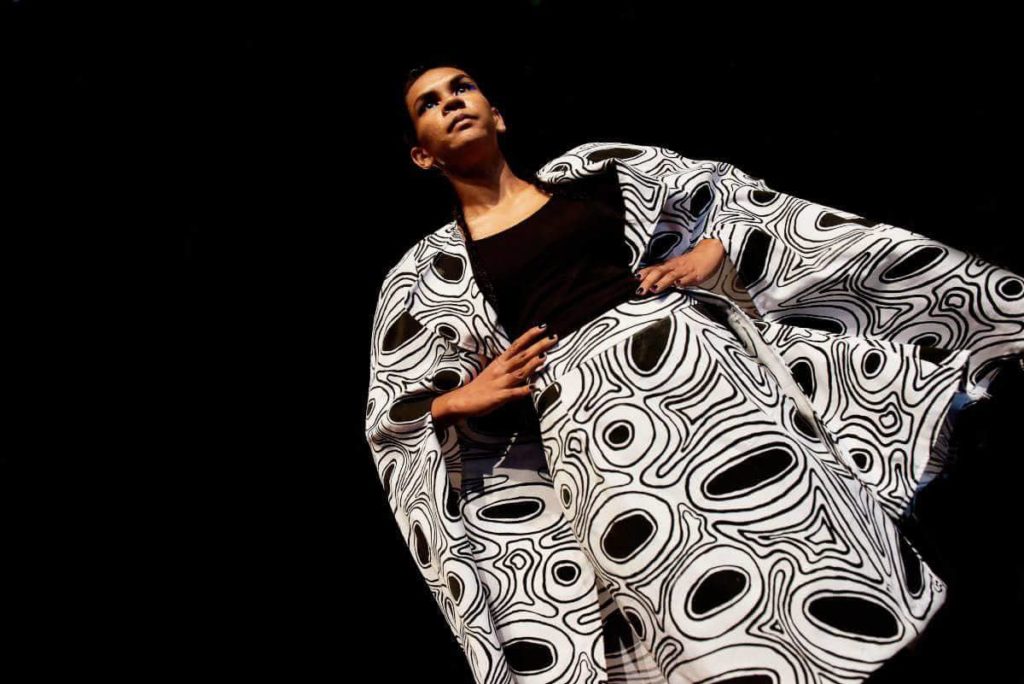

- Philomena Yeatman fabric, 2016, model Shernell, photo: Wayne Quilliam

- Philomena Yeatman basket imagery in Cairns, 2-16, Shields Street public art space

Another descendent, Philomena Yeatman, practices her fibre skills in Yarrabah Art Centre. Yarrabah is an idyllic looking community at the end of a promontory south of Cairns. The Yarrabah troupe energised the crowd at CIAF, inviting fellow performers from other islands and communities to join their defiant war dance. Fashion from Yarrabah was one of the highlights of the CIAF fashion parade.

But it’s tough. Recent cuts in Federal funding have made life difficult for art centre manager Shannon Brett. She takes the long view: “As more money goes into mining, generated to find jobs to work in mines, that dig into this country, this sacred line, the arts are pushed aside. I refuse to give up.” High pre-sales at the Darwin Art Fair seem a vindication of her belief in the talent at Yarrabah.

Yarrabah has been able to feature Philomena Yeatman’s large baskets and mats in art fairs. As a child, Philomena went collecting pandanus with her grandmother. She learnt the mysteries of the noni root, which could create a variety of colours, from orange to black. As an individual artist she has had some great successes, such as a commission for the Australian Parliament.

There are a number of settler fibre groups that offer support, as well as produce their own work. Okka Wikka has been working for 30 years to foster basket weaving skills. It was founded by Kate and Stuart Campbell, whitefella basketweavers, who were drawn to the north Queensland nature and culture. Stuart Campbell is currently focusing his attention on developing a school curriculum to ensure the skills are passed on.

- Marion Gaemers, Straw room

- Saltwater Creek Basketry group sewing seeds for a Sculpture Botanica in Cairns, October 2016

In Cairns, the Saltwater Basket Group has initiated many projects including workshops with Rhonda Brim. I encountered them at the Cairns Botanical Gardens, where they were making work for Botanica, a sculptural exhibition of works made from materials foraged from the gardens. The public gardens offered a working space that would not otherwise be contested by land claims. Importantly, they invited Delissa Walker to participate and she is creating an installation in honour of Wilma Walker, which will include elements of her life story, including the dilly bag where her grandmother was concealed from the missionaries looking for half castes.

Among them was Marion Gaemers, whose involvement in fibre and textiles stretches back to a macramé group in the early 1970s. She developed her skills at the Townsville College of TAFE, which were them nurtured at the Umbrella Studio Contemporary Arts. Gaemers coiling technique produces evocative human figures, seemingly formed from emptiness. She is drawn to public art for which there are opportunities such as Strand Ephemera which enabled her work with rather than against the impermanent nature of fibre. With few opportunities to exhibit fibre art in galleries, Gaemers gets by with community projects. She has been successful in organising many projects that activate Townsville’s city center and foreshore, such as the 2016 Weave the Reef / Love the Reef.

- Quandamooka Elders, Mary Burgess and Sonja Carmichael with traditional gulayi dilly bag from The University of Queensland Anthropology Museum collection. Photography by Nikki Michail, Sustainable dreamingwww.sustainabledreaming.org

- Photography by Nikki Michail, Sustainable dreaming www.sustainabledreaming.org — with Sonja Carmichael, Freja Carmichael, Leecee Carmichaeland Chantal Henley at Redland Art Gallery.

A little further south, Minjerriabah (North Stradbroke Island), Quandamooka Country has been the scene for the presentation of fibre as art. Minjerribah is the site of the poet Oodgeroo of the Noonuccal’s fabled cultural centre Moongalba. Today, the work of the Yunggaire weavers plays a significant role in cultural revival. Curator Freja Carmichael used Arts Queensland funding to host workshops in Minjerribah (North Stradbroke Island) involving her mother Sonja which revived the making of local baskets, particularly the traditional gulayi dilly bag with a diagonal pattern made from yunggaire reeds. Earlier workshops hosted others from the broader area, such as the Wake Up Time weaving group from northern New South Wales. While the techniques were collective, artists were encouraged to tell personal stories through their works. This resulted in Yunggaire weavers display in Gathering Strands exhibition at Redland Art Gallery, Brisbane, July 2016.

We see in the tropical north-east of Australia a number of individuals who are dedicated to sharing their knowledge in using indigenous fibre. Thanks to them, fibre traditions have shown remarkable resilience in surviving the violence of colonisation, and the determination of missionaries to bury the culture of its first peoples. But now it faces a new threat with the technology of distraction, which encourages a kaleidoscopic hyperopia (the condition when it is easier to see the distant horizon than what’s at your feet). I suffer from whitefella hyperopia myself. But as camp dogs are useful in alerting humans to distant disturbances, it may be useful to take an overview of this fibre practice.

Besides the beauty of the objects themselves, the value of fibre seems often as a testimonial to the maker. Projects like Gathering Strands provide a successful platform for these stories. But access to these kinds of projects is dependent on the existence of an art centre or gallery dedicated to this practice. Many slip between the cracks. Is the production of unique art objects the only pathway for survival?

The series of Living Treasures organised by the Australian Design Centre (Object) offered an important form of recognition through touring exhibitions. There is reason to look more closely at how the system of “Living Treasures” operates in Asian countries like India and Japan, where the official recognition of Master plays an ongoing role in supporting models for unique creative techniques. It seems that a nation as rich as Australia should be able to provide recognition and support for those who play a critical role as custodians to skills that are unique to our culture. Let’s see how this idea travels as we head west to the other end of the continent.

The dilly bag is not only a culture object worth preserving. It can be a symbol for the act of caring for a future generation itself.

Author

Kevin Murray is managing editor of Garland. Since taking up the Writer in Residence program at the Meat Market Crafts Centre in 1990, he has been dedicated to advocating the value of studio craft to a broad audience through writing and curating.

Kevin Murray is managing editor of Garland. Since taking up the Writer in Residence program at the Meat Market Crafts Centre in 1990, he has been dedicated to advocating the value of studio craft to a broad audience through writing and curating.

This project has been assisted by the Australian Government through

the Australia Council, its arts funding and advisory body.

Comments

i have been taught to weave the traditional Dilly bag by Aunty Doris Kinjun and Aunty Nancy Beeron along with Stewart and Kate here in Innisfail , i am blessed to have had this taught to me , my 1st little mindi basket we had a ceremony to which we burnt and the ashes were rubbed into my hands by Aunty Dorris and Aunty Nancy and now i weave in my spare time .. Awakening the traditional Mamu basket has been a gift given to me to pass on now, see my art page on facebook NGUGIYAM – FIRE FLY ARTS… https://www.facebook.com/NgugiyamFireflyArts/photos/

Thanks for sharing the link to the photos, Vivienne. It’s great to read how you are keeping those traditions alive. It would be great to learn more about the Mamu basket.

THANK YOU.

THANK YOU so much. Reassuring and heartwarming to find contacts and a network in support of ‘outsider artists’ struggling to find respect, peace and acceptance within mainstream arts.

New posts and any further information will be most welcome and appreciated with utmost respect and love for the arts and especially the people. Looking forward to getting more reviews and information and happy to think that here is an avenue of support where a shared dialogue of experience will achieve a healthy, established and rightful workplace for artists and their work; and everyone. Again, THANK YOU

Thank you. Are you an artist yourself?Do you have a website?

My sentiments exactly. With proper acknowledgement, may I please quote some of this opening statement as I Open the inaugural exhibition of the Mildura Basketmakers in late March this year?

I usually say much the same thing, but much more clumsily. Your words are beautiful.

Bev Manthey

Basketmaker, past president

Basketry SA

Thank you. That’s wonderful to hear. Let’s know of your exhibition and we can promote it.

Good Morning and thank you. Every goosebump is filled with inspiration and admiration for these extraordinary basket makers. Every space in a basket holds stories forever. Beautiful article.

The things our hands love to remember..thank you for sharing your stories with us.

Hello Kevin, I just had to let you know how I loved this article on Wilma Walker’s granddaughters. I had spent some time with Wilma at Mossman Nth Qld on visits to the area over several years to see my daughter. We sat on her verandah with my granddaughter and I taught her how to make a Melon Basket- a frame basket. She had been working on the commission of the three Black Palm Kakan baskets for the Queensland Art Gallery –and was needing a break. She spoke of the hope that some family members might learn to make the basket-and said a younger one seemed to be interested !!

So am so happy to hear her dream has been fulfilled.

The next year as we arrived and driving through the town of Mossman –I saw Wilma walking along the street carrying her small Melon Basket … and later on during the week I visited her … she was thrilled to tell me —that a tourist had walked up to her that day—as she was taking her basket home from the Naidoc week Art Fair…. asked her if she made it, she said ‘yes’ and sold it to her.

I caught up with Garland Magazine recently –when researching the plant Diplarrena moraea for basketry, and saw the Gwenn Egg article. I am currently writing a book on Indigenous use of Australian plant fibre. Keep well Kevin, Pat Dale