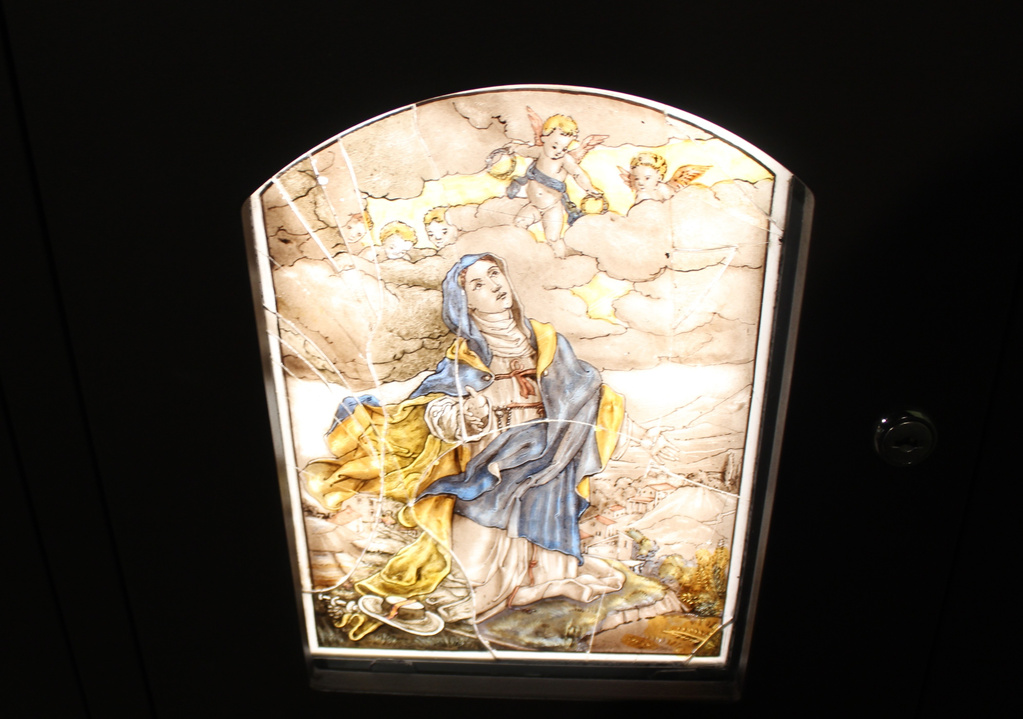

15th to 16th centuries silver stain and vitreous paint on glass panels from both the Grand Carmel Convent, Antwerp, Belgium, and Winchester Cathedral in England.

Pamela See talks with Michael Strong about the Abbey Museum of Art and Archeology and the art of stained glass that it celebrates.

In early 2025, through the assistance of the Queensland State Government and Creative Australia, the Abbey Museum of Art and Archeology (AMAA) opened an additional gallery at Caboolture on Kabi Kabi Country. Its inaugural exhibition, Inspired Images: The Art of Faiths, celebrates the diversity of a collection established by Rev John Ward between 1929 and 1945. His innovative Abbey Folk Park was situated in New Barnet, North of London. The open-air museum offered an immersive educational experience that was novel in its time. The artefacts were housed within reconstructions of historical buildings, including wattle and daub huts, a tithe barn, and a Roman villa. Much of the collection was sold after the Second World War, with the remainder eventually brought to Queensland. It stayed in storage for many years. In 1986, the institution was re-established as the AMAA. The new art gallery showcases an array of artefacts that evidence the diverse ways people have perceived divinity.

For craft practitioners, Inspired Images: The Art of Faiths also offers ground for comparing the techniques and materials used to fashion them. Central to this exhibition are examples of the stained glass for which the AMAA is celebrated. Presented are fragments, made between the fourteenth and sixteenth centuries, from Winchester Cathedral in England and the Grand Carmel Convent in Belgium. The paintings include a cartonnage panel from Ancient Egypt’s late period (c 664-322 BCE), vellum manuscripts from Medieval England (c 500 – 1500 CE), and an early Renaissance (c 1425 – 1525 CE) Flemish oil on wood. Accompanying didactic labels classify each of the objects by period, style or school. On some, reference is made to key exemplars. The description of the baroque Grotesque Mask as drawn in the “manner of Peter Paul Rubens” is a primary example. The approach adopted by the museum’s Senior Curator, Michael Strong, served to track the trajectories of a variety of manufacturing and publishing techniques. From fine arts to architecture, students of creative industries could benefit from visiting the institution.

In June 2025, Michael Strong met with artist and educator Dr Pamela See to discuss the relevance of the collection to South-East Queenslanders.

✿ What sets AMAA apart from the innumerable Wunderkammers throughout regional Australia?

Interesting question – I don’t think we have ever been referred to as Wunderkammer, and certainly we are fairly unique in Australia. We focus on the human story told through the collections. The permanent display chiefly chronicles civilisation from an archaeological perspective over the last million years. The new art gallery, opened in February this year, has a collection of medieval, renaissance and baroque paintings, [which is] unmatched in a non-government museum in Australia. And, we are able to put a large number of Greek, Cypriote and Russian icons on display for the first time. We have included figurines, manuscripts, ceramics and sculpture[s] of deities and heavenly beings. However, the nearby Abbey Church is the venue for the museum’s wonderful collection of medieval, Renaissance and Gothic Revival stained glass—easily the most significant in Australia. This came to the Abbey Folk Park in 1934 from the disposal of surplus glass acquired by the well-known firm of Charles Kempe.

A Flemish, Late Renaissance (16th to 17th centuries) stained glass panel painted using coloured oxides, vitreous paint and silver stain of Balthazar, one of the three Magi.

✿ Can you tell us a little more about the stained-glass pieces in the new exhibition? How were they crafted?

There is a small but spectacular display of stained glass from Winchester Cathedral and Flanders in the new gallery. The museum holds about 20 panels of stained glass. Another 400 fragments came from Winchester Cathedral, after Kempe’s restoration in the 1890s. He removed the Renaissance fragments that had survived the iconoclastic Protestant and Puritan reformers. Fortunately for the world, many of the priceless fragments were saved by one of Kempe’s staff, Alfred Tombleson, who eventually presented them to the Folk Park. These tiny details are all that are left of three huge windows featuring a Nativity, Jesse Tree and themes from the Book of Revelation. [They were] probably made by the King’s glazier and installed into the Lady Chapel between 1490 and 1510. Most of the Winchester glass is from a series of headers protected by stonework that feature golden-haired angels and floral designs from the Tree of Jesse.

✿ What was the curatorial intent behind your inaugural exhibition?

To demonstrate the antiquity of belief, the multitude of deities and the many paths to divinity. Thus, a 4000-year-old mother goddess from ancient Iran is flanked on one side by a huge photo of a 17,000-year-old Aboriginal ancestor spirit rock painting. Through the open display are glimpses of Christian Madonnas and Child, by artists such as Honthorst, Cranach, Raphael and Sassoferrato. The limestone sculpture of the Lamentation of Christ is our centrepiece, and this shows the body of Jesus being placed in the tomb prior to the Resurrection. However, we have just discovered that it contains in [its] iconography… ancient imagery, reaching back to Celtic mythology, the Grail legends and a thirteenth-century French epic of Huon of Bordeaux.

✿ Who was Rev John Ward?

John Ward (1885-1949) was a remarkable, multi-faceted savant and author, and his views reflected the diverse paths people take to divinity. He started life as an Anglican and was one of Britain’s leading Freemasons. [B]ut [he] became fascinated by the ancient wisdom of India’s great religions, similar to Father Bede Griffiths in more recent times. He started a small mystical community in 1929. [B]ut, despite its historical name and associations, AMAA is NOT an evangelising institution in any form. The Folk Park closed down in World War II, and Ward and his community left England for Cyprus, where he died in 1949.

✿ Who are the people who assist in the running of and engage the services of this museum? Who else might benefit from a visit to your institution?

We would welcome art students and artists. The museum does not currently focus on contemporary artists (apart from the Kabi art installation), as we don’t have space even for the current collections. We have a small paid staff (Curators, events, education and marketing) and a wide number of volunteers (around 350). We have about 10,000 students a year who come to do archaeology programs. But we are trying to build a greater art emphasis. We also have the medieval festival, which attracts about 25,000 to 30,000 visitors and provides the bulk of our income.

A Baroque (early 17th to mid-18th centuries) devotional window painted using vitreous paint on a single panel of glass.

✿ Considering that a majority of the artifacts were donated by British residents in the 1930s, what is your present collection policy? Does the institution have a different direction for this new century?

We have a collection policy that embraces all cultures and belief systems. We still acquire objects from time to time that are useful from an educational viewpoint. We do not accept objects that have been looted without agreement from the country of origin. However, naturally, as the collection came through England at a time when the empire was collapsing, it does have many items that came about through colonial acquisition. We do not reflect this in our displays, however, and focus on the cultural context.

✿ With a number of copies of paintings in this collection, can you speak to their value during the time of their production and in the present?

It’s difficult to discuss the value of paintings or artworks. Suffice to say, this is a very valuable collection indeed. And when you say copies, this was a way that artists made their work available to a wider audience before the advent of photography. Copies are increasingly being seen rightly as having considerable value and importance, depending on the artist who made the copy. So many great artists made copies of other works. Rubens copied Titian, for example. And, Charles I of England commissioned van Eyck to make copies for his Royal Collection. In one case, the primary work was destroyed in a bombing incident last century and we hold one of the major copies along with the National Gallery in London.

Further reading

The Abbey Museum of Art and Archaeology. (n.d.). Art of Light – Stained Glass.

The Abbey Museum of Art and Archaeology. (2019, October 19). “Museum Reborn” – The Story of the Abbey Museum [Video]. YouTube.

Bauman, G. (1986, Spring). Early Flemish Portraits 1425-1525. The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, XLIII (4).

Barzun, J., Hearsey, J. and McMillan, S. (2025). The Middle Ages.

Ginn, G. (2012). Archangels & Archaeology: J.S.M. Ward’s Kingdom of the Wise. Liverpool University Press.

City of Moreton Bay. (2022, June 29). Abbey Museum bolstered by huge $2.1 million budget announcement.

Hall, M. (2018, December). Charles Eamer Kempe – the stained-glass designer who kitted out England’s churches. Apollo Magazine.

Hill, M and Allen, J. (2018). Egypt in the Late Period (ca. 664–332 B.C.). Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Strong, M. K. (2020). Glorious Glass: Stained Glass in the Abbey Museum Collection. Cornerstone Printing, Board of the Abbey Museum of Art and Archaeology.

Strong, M.K. and J. Jackson (2025). Inspired Images. The Art of Faiths. Cornerstone Printing, Board of the Abbey Museum of Art and Archaeology.