- Catherine Bell, Crematorium Vessel, 2012-13, carved, reclaimed floral foam, dimensions variable, Courtesy of the artist and Sutton Gallery, Melbourne

- Jenny Loft, Proximity, 2010 (detail), glass, metal and wood 48 x 51 x 28 cm Courtesy of the artist and Stephen McLaughlan Gallery

- Julia deVille, Bone Ring Majesty, 2016, 18ct white & yellow gold, garnet, cognac diamonds, dimensions variable, Courtesy of the artist

- Linde Ivimey, Peepo, 2015 (detail)

- Linde Ivimey, Texta Lepus, 2011-12 (detail)

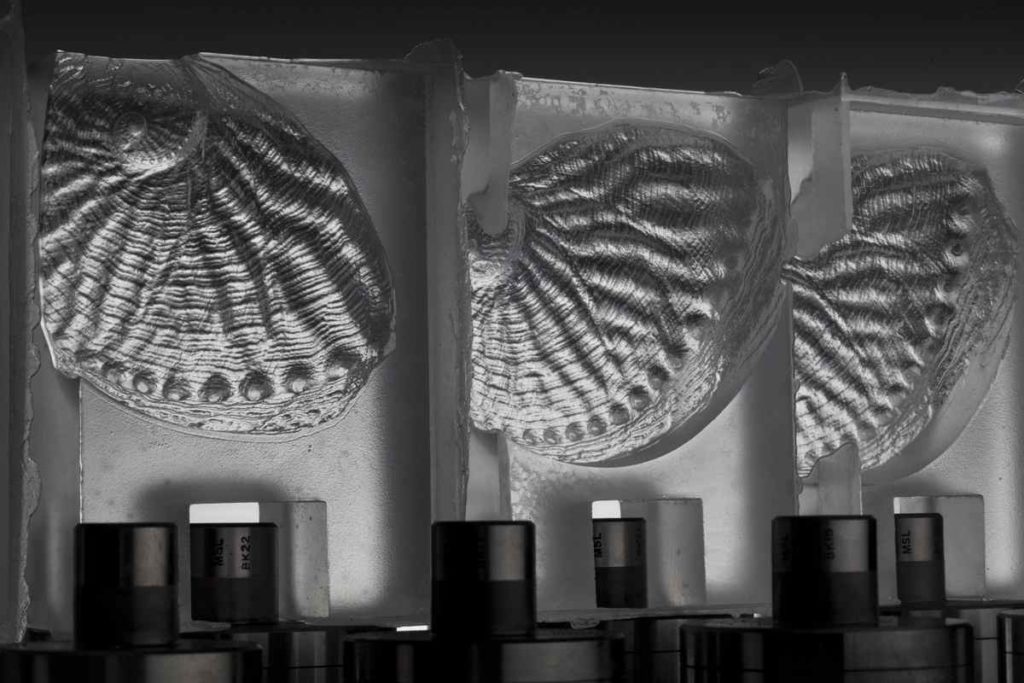

- Trent Jansen for Broached Commissions Work created through key collaborations with Rod Bamford (Ceramic), Oliver Smith (Copper and Brass) and Vicki West (Bull Kelp). Briggs Family Tea Service, 2011

- Yvette King, Trophy, 2009, (detail) cast bronze, 24 crt gold, 88 x 40 cm, Courtesy of the artist

Many rituals and ceremonies are so commonplace we forget that they dominate our lives, from days of birth to days of matrimony to nights of death – Ceremony is everywhere.

In my travels I have seen many other rituals that are cornerstones of a variety of cultures. I have seen young boys in Arnhem Land being painted in preparation for circumcision, chickens being slaughtered as part of Voodoo ritual in the bayous outside New Orleans, bodies laid on the open to decay in the open air in the mountains of Bali, supplied with clove cigarettes (even the dead keep smoking there.) In Tanzania I have watched a Massai warrior dance and chant himself into a trance, white foam flecking his lips and in Paris I have attended an Easter Mass in Latin at Notre Dame and in Jerusalem watched the Jewish faithful place prayers at the Wailing Wall. The list seems endless.

In each and every case there are the accoutrements. Mine is a battered tin camping cup which accompanies me on every bush trip, but which long ago became the daily vessel for coffee. But then there are the payback spears, the sacred bones and knives, the holy books, the Catholic rosary and the Jewish Tefillin, the Buddhist incense, the Hindu shrine and the Muslim prayer mat. Accouterments make ritual concrete. They make the irreal real. They allow us to see and feel our beliefs. Whether found in nature or crafted by specialised artisans, such objects inspire belief and, at times, terror.

This exhibition uncovers moments and physical rituals that were at times macabre and others celebratory, moments both neurotic and cathartic. Hints of religiosity abounded and indeed in 1907, in his text Obsessive Actions and Religious Practices, Sigmund Freud suggested that religion and neurosis have considerable correlations, that the repetitious and compulsive nature of neurosis is “an individual religiosity,” while religion is a “universal obsessional neurosis.”

The exhibition includes an artist who would create a new shroud for each time she underwent treatment for cancer. Another artist cast and then gold-plated her grandmother’s torso, complete with a grotesque hernia, in a work that evolved from her caring for and bathing her grandmother each week. Another artist taught herself the art of taxidermy to create a bizarre menagerie—death did indeed hover closely, but so did healing and celebration. Ancient traditions were acknowledged such as kopi—a traditional Aboriginal mourning practice where clay head ware is formed around the head of the mourner. Similarly drawing upon tribal tradition, another artist made use of the bilum—the painstakingly designed woven bags that hail from his tribe in Papua New Guinea called the Amam. Yet another artist crochets blankets, which she imbues with blessings as she works with the resulting floor piece made for viewers to stand on in bare feet in the hope that it will be a conduit to connect people to the earth. There are crematoriums and tea sets and jewelry and accouterments to ceremonies that are both alien and plausible from mummified cats to bird talons.

Strange creatures, totemistic entities unrelated to the normal rules of nature, abound. Belief—that which is at the heart of ceremony—was endemic. Both mourning and healing found expression in materials ranging from bone to cloth to glass to timber and metal.

Of course, the very nature of committing to the life of an artist is itself not unlike joining a priesthood. Long hours of solitary contemplation followed by spasms of fervent activity. There are rules, both self-imposed and dictated by the media in use. There is the chapel, otherwise known as the studio, often a site of deprivation but an abode that the artist feels compelled to spend often thankless hours. Even outside the studio boundaries, many of the artists here undertake the ritual of fossicking, spending vast quantities of time seeking out bones, rocks, timber and grasses to amalgamate into alchemist entities. But in this cargo-culture age, it is not just natural materials that are required for the Ceremonial, found objects and detritus left over from commercial use also take on magical qualities. Ceremony is all around us.

Author

Ashley Crawford is a freelance cultural critic and arts journalist based in Melbourne and is the author of a number of books on Australian art, including Wimmera: The Work of Philip Hunter (Thames & Hudson) co-author of Spray, The Work of Howard Arkley (Craftsman House). He is a regular contributor to The Age, The Australian, The Guardian, The Financial Review, The Sydney Morning Herald, Australian Art Collector, Art Monthly, Eyeline and numerous other publications. He is also the former editor of Tension, World Art, 21•C and Photofile magazines. He trained as a journalist in the late 1970’s and is currently a PhD Candidate at the University of Melbourne.

Ashley Crawford is a freelance cultural critic and arts journalist based in Melbourne and is the author of a number of books on Australian art, including Wimmera: The Work of Philip Hunter (Thames & Hudson) co-author of Spray, The Work of Howard Arkley (Craftsman House). He is a regular contributor to The Age, The Australian, The Guardian, The Financial Review, The Sydney Morning Herald, Australian Art Collector, Art Monthly, Eyeline and numerous other publications. He is also the former editor of Tension, World Art, 21•C and Photofile magazines. He trained as a journalist in the late 1970’s and is currently a PhD Candidate at the University of Melbourne.