- Rodney Glick, The boot, photo: Robert Finlayson

- Photo: Robert Finlayson

- The dancing girls; photo: Robert Finlayson

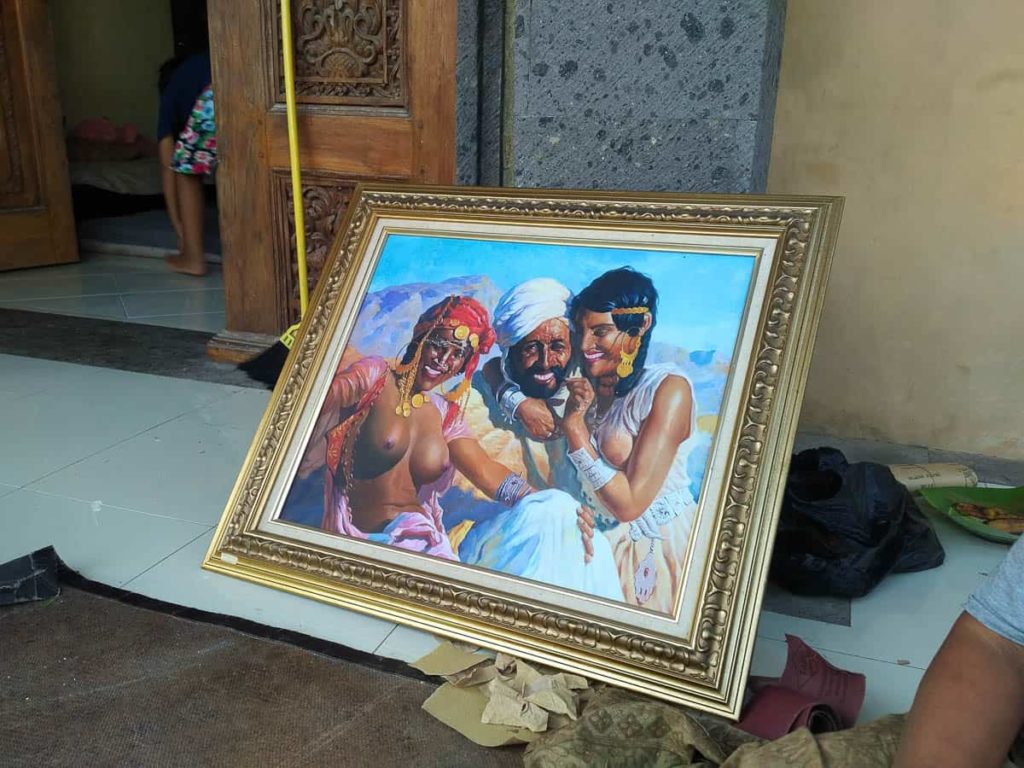

- The Turkish painting, photo: Robert Finlayson

- Wayan Darmadi, photo: Robert Finlayson

- Rodney Glick and Komang Suryana, photo: Robert Finlayson

- photo: Robert Finlayson

- photo: Robert Finlayson

- photo: Robert Finlayson

- Rodney Glick, minum Aqua, Apel, Liswati, photo: Robert Finlayson

- The Everyone t-shirt, photo: Robert Finlayson]

They’re boots. Military field boots, I’d say; they have that look about them: pugnacious toe; thick, corrugated sole; long tongue and half-laced upper; although there is an unexpected zipper along the shaft. Nor is the colour what one would expect. By rights, these boots should be blacks, greens or sands and camouflage patterned.

Adding to the oddity is that one of the boots is cradled in the lap of a woman who is softly rubbing its tongue—like she’s massaging a baby—with emery or sandpaper, ever so slightly abrading it. Looking more closely, I note a fine coating of wood dust on the batik-design cloth the boot rests on. This boot is made from wood.

Perhaps it’s easier to discuss the cloth. It has a grey-green background with dot-painted dragonfly-and-floral motifs picked out in red and white, which is unusual and certainly not from the classical repertoire of the batik-producing countries that I know of: Indonesia, Malaysia and Kenya. I like the design very much and wonder how it is that the cloth is being used as a protective rag and conclude it must be a printed, factory item with batik-like design rather than made using the actual batik technique. Otherwise, it would not be treated so perfunctorily; hand-drawn batik takes months or years to produce a single two-metre length of cloth. Consequently, it is treated with respect for the craftwork and high cost and, occasionally, also for the spiritual power that surely must reside within, beckoned and protected by the symbols in the pattern itself.

Alas, I don’t have time to muse more on this because my attention is drawn to a beautifully carved, wooden, double-door frame that I know in Java is called a gebyog and through it to a white-floored room where three young girls in jeans, skirts and t-shirts are practising a fast-paced, Balinese traditional dance to the sound of a gamelan, following the moves on a DVD player plugged into a big TV. The girls must be around 9 or 10 years-old. Swiftly and light-heartedly, more or less precisely, they copy the TV dancers’ hand gestures, twirls, dips, prances forward and back, and laugh and slap each other when they don’t quite manage it.

Suddenly my attention is distracted yet again as a framed painting is carried through the room, weaving its way between the girls, who laugh again more loudly as they dodge the bearer and the frame. It ends its journey propped against the wall next to the woman who’d previously been rubbing the boots and now was laughing as loudly as the girls albeit in a deeper more knowledgeable tone.

The painting was a prized talking point, brought out for visiting artists from within Bali and beyond. Gifted by a passing Turkish client to the woodcarver in whose house and studio all this was taking place, it portrayed in garish uber-realism two women embracing a white-turbaned man. All three were painted grinning, clearly indicating they’re sure you would like to join their party, despite the background suggesting some blasted desert. Everyone around me was also having a great time discussing the picture, making lots of jokes in several languages.

“But, look, what are we going to do with this?” interrupted Rodney Glick, who was the reason I was in the midst of this mirth.

He was holding a military helmet, which, I was assured, was the real thing: Kevlar; it weighed a lot. It was bought at Senen Market in Jakarta and came complete with green camouflage-cloth covering. Post-facto research suggests it could be one of three types of helmet used by the Indonesian military. Anecdotal research suggests it could be part of the equipment of 30 different national militaries, which are manufactured in Sukoharjo in Central Java Province. According to the Jakarta Post, Indonesia is aiming to become one of the biggest exporters of military uniforms in the world.

“Something domestic?” I hazard.

It was around 12 noon in the village of Kemenuh, which is about 15 minutes’ drive on motorbike from the town of Ubud in the Indonesian province of Bali, which isn’t too many degrees south of the Equator, and I’m enjoying the suddenly swift runs of sweat down my face and the sides of my body and wondering if I could have a little lie down under a coconut palm to enjoy them more fully. Rodney is having none of that. He’s tramping around the tiny, open-air studio with the helmet, dumping it onto the floor suddenly, turning it over, turning it back, moving it to the head of an incomplete statue of a portly man sitting in a lotus position while draped in a camouflage jacket, before dumping it upside down—almost in slow motion, without much conviction, as if he senses something might be happening—onto a drinking-water dispenser. He steps back and looks.

“That’s not bad. Right?” he announces.

“What?” asks Ketut Suardika, suddenly attentive. He’s the woodcarver and our host. He prefers to be called Apel because it means something natural, fresh and tasty in both English and Indonesian. “What? All of it?”

“Yes, the whole thing: helmet and water dispenser,” confirms Rodney.

“Oh, okay,” answers Apel. He continues staring at it for 10, 20, 30 seconds, and then: “Like that? Terbalik? Apa sih?”

“Yes, upside down, just like that, so we can see it clearly. If it’s the right-way up then it blends into the galon.”

Apel nods and another moment or two pass; we all continue to stare at the assemblage.

Rodney breaks the silence: “Just carve each bit separately; like they are.” He takes a photo with his phone. “No need to find a big bit of wood; too much trouble.”

Apel nods again. “Good. Hard to find and expensive.”

He had started carving at around the age of 12, by himself. His father was a farmer and there were no direct family or trade influences on him other than those gleaned from growing up not far from the renowned woodcarving village of Mas.

“I looked at books and practised on wax,” he explained. “I carved for many different people from everywhere. Jesus is always popular,” he added, pointing to a life-sized crucified figure prostrate at the other end of the porch. “But it’s not a stable income. I have a family. I managed those villas over there,” gesturing towards a row of steep roofs on the other side of the rice field, “for seven years, but for the last three have been only working with Rodney. And sometimes Jesus,” nodding amusedly towards the almost-completed work. “I like the imagination, the challenge, with Rodney. Good collaboration. I’m bored with always doing human figures.”

Liswati is looking at the helmet on top of the water dispenser and smiling. She’s another visiting artist: a dance-theatre professional from Jakarta.

“You know the joke?” she asks me, nodding towards the unlikely assemblage.

I don’t. What is it?

“If someone is hot-headed and violent, we tell them to minum Aqua: drink water; calm down, relax.”

The French company Danone’s Aqua is the dominant brand in the bottled-water market in Indonesia and the term is often used as a synonym for water. Calming the military has been one of the more serious projects of Reformasi, the period of political restructuring after the end of the New Order regime in 1998 when the 31-year reign of former general cum president, Muhammad Suharto, finally ended.

So it seems Rodney had, presumably inadvertently, made at least an Indonesian joke—perhaps also political commentary—into plastic reality. How was that possible for a visual artist from Australia who spoke only rudimentary Indonesian? Further, how could he not only inspire enthusiastic collaboration with artists and artisans from a range of backgrounds in his adopted country, but also make sophisticated visual jokes that span languages and cultures?

I really did need to lie down under a coconut palm for a while and think about this. While there, I would, of course, work my mobile phone, asking Google its opinion.

Rodney Glick, according to sites on the web, is an Australian passport holder and visual artist from the city that sports the contested claim of most isolated on Earth: Perth, in the state of Western Australia. In a sprawling, quiet, clean and uncluttered urban environment surrounded by thousands of square kilometres of desert and ocean, he has forged an international career through representation in festivals, exhibitions, publications with works that have been acquired by private collectors in Europe and North America, the National Gallery of Australia and several Australian state government galleries, which is considered the pinnacle of critical achievement in the fiercely independent, if also contested, curatorial environment of contemporary Australia.

If you search for his name online you will find an intriguing list of links with titles such as, God-favoured, Rodney Glick: Surveyed: Lawrence Wilson Art Gallery: The University of Western Australia; Rodney Glick | Ubud Food Festival; Rodney Glick: Superfictions; Seniman Coffee Studio: artful coffee in the heart of Bali; Glick International; Rodney Glick gives Hindu deities Krishna and Radha a makeover.

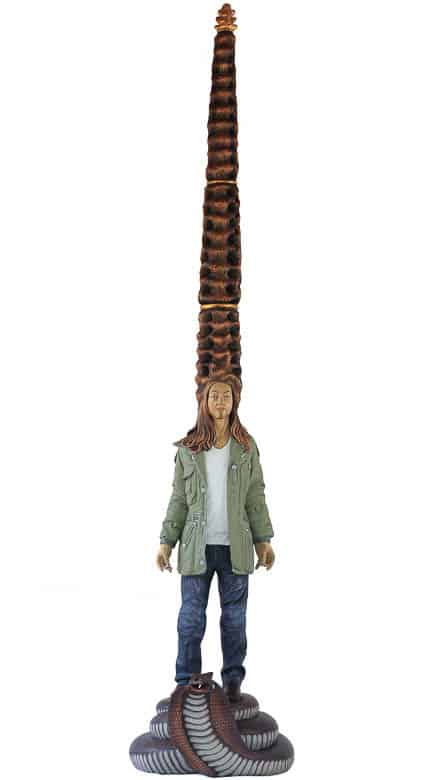

Of these, Glick International will give you the most complete record, albeit patchy and incomplete, of what most people would cheerfully or otherwise declare were works of visual art. Rodney Glick gives Hindu Deities Krishna and Radha a Makeover will present a part of the background to what he says most inspired him to set out on making these groups of statues, called the Everyone series (you can buy an original t-shirt with Everything Happens to Everyone across the chest when you visit Seniman Coffee Studio in Ubud. Seniman is Indonesian for artist).

“I visited the Smithsonian Institute in Washington DC in 2006 and there was an exhibition of Indian sculptures”, Rodney explained to me at his home in Lod Tunduh, a few minutes’ drive from Ubud. “Many were multi-armed and it occurred to me, for the first time, that this represented a sequence of movement, with all stages visible and frozen in the moment. I hadn’t thought about it like that before. It inspired me to set out to make statuary that featured ordinary people to get across the idea of animation. It was my epiphany.”

When he returned to Perth, he asked colleagues if anyone knew of carvers who could make the works he conceived. None did, except Christopher Hill (1944–2014), who the Australian Centre for Concrete Art described as “a great friend to many Perth artists, who knew him as a kind, generous and elegant man who actively and passionately connected with near and distant art communities. His passion for collecting extended particularly to Balinese art and this interest developed into researching painters in Balinese villages.”

One of those artists only painted army generals; another depicted the gods with multiple sets of genitals because “gods can do what they like”. Chris introduced Rodney to this milieu, which included the carver Made Leno, who also produced life-sized statues of the crucified Jesus for churches throughout the archipelago and reliefs of the Last Supper for private buyers in Jakarta, stacked in his studio alongside carvings of Balinese Hindu gods and their endlessly variable avatars, numerous Buddhas and anything commissioned by anyone. Rodney eventually collaborated with Leno and painters Wayan Darmadi and Dewa Tirtayasa on the initial works that led to the Everyone series.

By “everyone”, I speculate Rodney means that we, each of us, really have no single identity but rather multiple ones that are fluid, dynamic. We shift our roles and attitudes, even our personalities, to suit our circumstances and, like the multi-armed gods in his statues who are but ordinary individuals in everyday clothes, we embody the elemental forces epitomised in the Hindu Trimurti: Brahma the Creator, Vishnu the Facilitator and Siva the Destroyer.

- Rodney Glick, Everyone no. 177, photo: Tony Nathan

- Rodney Glick, Everyone no. 100 – Jason, photo: Tony Nathan

This isn’t so much about a specific religion or religion as it is largely understood, but about our wider sense of the world and what happens in it. The Trimurti can be seen as the fundamental forces at work in all of us and throughout the universe.

I had met Rodney in Perth and we both coincidentally found ourselves living in Indonesia at the same time, he in Bali and me in Jakarta and kept in touch so it has been quite a pleasure to research and write this essay. Rodney’s wedding in Bali combined Taiwanese, Jewish, Australian, Balinese and broader Indonesian rituals, meanings, speeches, gestures and guests. It was comfortable, odd, uneasy, relaxed, amusing, serious, peaceful, threatening, hilarious, sombre, rich, poor, international and very local and as such encompassed the whole gamut: everything happens to everyone. We are each a multi-armed god with all our attributes, skills, failures, hopes and fears flailing around us. From what I’ve learned about Rodney, it seems he wants his work to remind us that art and religion reflect the basics of life. And death.

One of his early, secondary works in Bali was a number of jewellery pieces made of animal bone, executed by carvers in the renowned artisanal district of Tampak Siring to the east of Ubud. He worked with a number of artisans there to produce necklaces of human skulls, tiny gas bottles, and recalcitrant, allegedly stackable, miniature plastic chairs.

At around the same time, he was producing a series of statues based on Indian Hindu miniature paintings dealing mostly with the Siva aspect of the Trimurti, discussed in Rodney Glick gives Hindu Deities Krishna and Radha a Makeover, some of which were exhibited at Salihara Gallery in Jakarta in December 2009. The response from viewers was mixed, many being confronted by such sights as Everyone No. 75 of a headless, tracksuited body standing on two clothed lovers, spurting blood being drunk by red and blue men; Everyone No. 53 of a man hanging his severed head by the hair; Everyone No. 35 of an eight-armed man astride a bull holding four bloodied knives and four naked corpses; and Everyone No. 64 of a beautiful young woman wielding blood-soaked knives, a severed head and a bowl of blood. She stands astride a corpse that lies supine but aroused on a burning funeral pyre. The blood from the bowl she is holding drips onto the corpse.

- Rodney Glick, Everyone No. 35 – Manbull, photo: Tony Nathan

- Rodney Glick, Everyone No. 75, photo: Tony Nathan

- Rodney Glick, Everyone No. 53 – Three heads, photo: Tony Nathan

- Rodney Glick, Everyone No. 64, photo: Tony Nathan

Chris Hill wrote the catalogue essay for this series, called Punching the Devil, arguing that “these works from the Everyone series seduce us through the fineness of their form and the skill of their making. They intrigue us because of the mix of ancient and modern, religious and secular, Eastern and Western and finally invite us to confront deep and basic states of mind that we all experience but that we might prefer to leave concealed. And we might find some comfort in knowing that the states of mind we share with the rest of humanity we also share with the gods.”

I asked Apel, who did not carve the works, what his Balinese friends who weren’t artists thought of them. Did they startle and disturb them as much as that reported by some Westerners?

“They said the works went too far,” he answered. They knew they represented avatars of Kali, of Durga, of Shiva but thought they were extreme examples that fell outside the framework of how they thought such things should be depicted.

Bali is no different from other provinces of Indonesia—whether predominantly Hindu, Muslim, Christian or an indigenous religion—in that it is largely conservative, particularly, regarding the expression of religious ideas in either concrete form or in people’s words and behaviour. Balinese Hinduism does, however, share a syncretism similar to Java’s kejawen religion (a blend of indigenous, Islamic, Hindu and Buddhist elements) in creating a complete and interactive worldview that features three realms: that of the gods, of humans and of the spirits.

“Balinese culture is becoming more Balinese thanks to tourism,” noted Apel. “The more foreigners visit Bali, the more protective we become of what makes us Balinese. And that is very local. The traditions in my village are similar but uniquely different from those in the village over there. And now we place even more emphasis on them. Which reminds me,” he turned to Rodney, “that in the first two weeks of August there is a big ceremony so I won’t be doing any carving. And the man who does the refined carving with me, he hasn’t been here this month because he has a ceremony in his village. So things will be slower than usual.”

Informed by this rich, multi-layered content, I returned to one of my original questions about Rodney’s transition into a completely different cultural milieu and how he was able to make that visual joke.

“I don’t think of the concept before I do something,” Rodney replied. “With the water cooler and helmet I just liked the form; the joke was something that the Indonesians present made amongst themselves from the unexpected juxtaposition of objects; it was just a fortuitous coincidence; the joke doesn’t exist in English or in my visual thinking.”

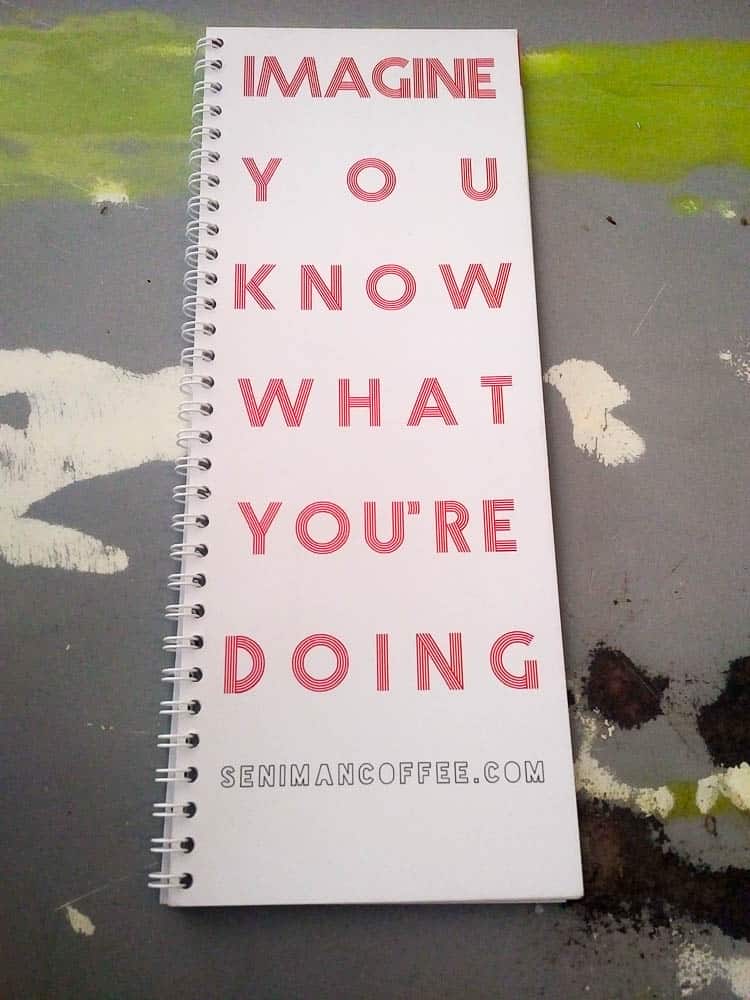

Imagine you know what you’re doing

Linked to this kind of willful ignorance is perhaps the next-most important guiding slogan—all of which set out to mock motivational and marketing taglines—for Rodney Glick: “Imagine you know what you’re doing”. It features on the front of the menu at the newly opened Seniman at Tony Raka café and the original Seniman Coffee Studio, in the villages of Mas and Ubud, respectively.

The phrase also adorned the walls of Fremantle Arts Centre in Western Australia (WA) in 2014 at a group exhibition called, Bali: Return Economy, curated by Chris Hill and Ric Spencer.

Critic Victoria Laurie, in The Australian online under the title, A different Bali comes calling, wrote at the time that, “WA sculptor Rodney Glick, now resident in Bali, has embraced a Balinese aesthetic that turns even mundane objects—from daily flower offerings to funeral items—into artworks. Glick, who runs a design company and coffee shop in Ubud, designed timber rockers to bolt on to humble plastic chairs that are commonplace in Asia; plastic stools are replicated in teak.”

“‘Glick has adopted the idea that there’s no tension between creating art and every other item of domestic and ceremonial life,” said Hill.

Rodney’s journey to becoming the founder of an emergent art-coffee empire that has attracted high praise from national and international connoisseurs for both its aesthetic design and its artful production of the beverage is intimately linked to his life as an artist in Bali.

“I had no idea about coffee 8 years ago, other than I liked to drink it,” he claimed. “My then-business partner in Bali had bought a coffee plantation in Tabanan [a district in Bali] to supply his hotels but had more coffee than he knew what to do with. So I thought I’d build a kaki lima, which is a push-cart common throughout Indonesia, and sell the coffee from it. That didn’t really fly but David Sullivan, a marketing guy I was designing things with for a few years, found a rental property in Ubud that we could use as a café. We really started as just a design exercise to amuse ourselves. But then we realised we had to make money.”

The “design exercise” extended not only to the logo and typography, but also to the furniture, crockery, soap (recycling kitchen waste), slogans and a range of unique merchandise, such as wooden antler bottle stoppers, glassware from recycled bottles and the increasingly famous “bar roker” chair.

“And now what has happened is that the coffee enterprise has become the frame,” argued Rodney during an interview at Seniman at Tony Raka, “the entrance to a gallery of works that stretches across physical and conceptual forms, from statuary through artisanal merchandise to construction of a form of capitalism that jokes at itself.”

Tony Raka himself, whose gallery the café fronts, confirmed that Rodney’s concept of blurring the boundaries between art and business was in line with his own vision of a creative hub.

“I like working with Rodney; he’s a good friend,” said Tony. “And his idea of an art café linked seamlessly with my vision of a place where creative forces meet for good, for creating new opportunities and also supporting the traditional. I’m Balinese and have my obligations to my community; I also need to expand my horizons and of course make money for my family and contribute to my community. Rodney’s idea was a good match with my gallery, collection and vision of a place where artists and friends can gather and make connections in a relaxed and friendly environment.”

For Rodney, the “frame” includes not only the two outlets, but also a coffee processing and exporting business as well as coffee training workshops, appearances at expos (including being the “face of Indonesian boutique coffee” in Taiwan), an educational foundation for staff and the imminent franchising of an archipelago-wide popular version of the Seniman café, likely called simply Kopi Seniman.

I asked Rodney to explain, given that much of Australian art history has seen artists positioning themselves as anti-business mavericks, despite the nature of the fine arts and crafts sector being provision of high-end objects to those with disposable income.

“Business, domestic life, drinking coffee, making art… the most mundane or the most exalted acts… they’re all part of the universal phenomenon of being human that everyone shares no matter their background, wealth or religion. In that sense, the coffee enterprise is part of the Everyone series. I should give it a number,” he joked. “Personally, it’s also an exciting new challenge that I would never have predicted as a possible future for me. Similarly, I wouldn’t have seen I would move to Indonesia. I had no ambition to do so; I just went with the flow.”

Wayan Darmadi also describes himself as “running like water” (lari seperti air) in his artistic process, having begun painting when he was in junior primary school, training as an artist after he finished school and then moving to Malaysia in 1990–92 to paint commercially on clothing and wood before returning to his village of Bona Kelod near Ubud.

I followed Rodney on motorbike to visit Darmadi (“Wayan” is an extremely common name in Bali and usually second names are used to ease differentiation) to try and understand how the pair worked together. The immediate impression was of a gentle and deeply thoughtful man. As well as being a highly regarded realist painter he is also a renowned rindik player, having most famously performed at the reception of US president Barack Obama at the East Asian Summit in 2011 in Nusa Dua, the convention area about an hour south from his home.

“My grandfather was my hero,” he explained by way of background, “and my biggest influence. He made statues and offerings as contributions to our community not for profit but for social reasons. I was very much inspired by him. I went to Malaysia for the experience, to learn more, and to make a little money.

“In the early 2000s, when I had married and started a family, I realised I had to learn from the spirit of my grandfather and provide support to others. The times had changed so I became a professional painter.

“I’ve been working with Rodney now for around 10 years. He is my best friend and part of my family. We exchange ideas all the time, like an east-west perspective. My own style is realistic so it transfers well to Rodney’s concepts even though the material is different from canvas. I enjoy all the work I do with Rodney because we ‘click’: we both like detail. I sincerely hope that we can continue our friendship and collaboration, which isn’t at all like a boss-employee relationship but one between equals, between artists. It’s very important to me. We are very good friends; it’s very sweet. I’m 45 now and my eyes are starting to weaken so I want to train younger artists, to start a school to train young painters. My ambition is that everyone is happy; money just follows.”

I followed the boots. Darmadi had them by now. He had painted the soles and was working on the rest as determined through discussion with Rodney. (As a side note, this was the first interview I conducted in which the interviewee took time out to climb a coconut tree to retrieve some prized yellow coconuts to serve to his guests. The yellow variety is apparently particularly good for pregnant women (none present at the interview, as far as I know)).

Lei Tai, a PhD candidate from the Department of Anthropology at the National Taiwan University, who had joined us on Rodney’s invitation, initially didn’t believe the boots we were looking at were carved wood. She had to touch them, pick them up and then express her deep admiration for the artistry and the conceptual challenge they presented. The Taiwanese, like the Japanese, as fellow and economically successful Asians, are highly respected by artists in Indonesia and, hence, this comment was very well received. What was to be done with these boots?

“Komang Suryana carved a set of discarded offerings and two generals’ hats, as well as some others,” explained Rodney. “We’ve been working together for about four years. I’m thinking we’ll combine all of these, and the boots, to create an assemblage. It might be that an army officer comes home and takes off his uniform, including his boots and hat, and tosses them wherever they fall, perhaps next to the discarded offerings to the gods or onto a water dispenser or plastic chair. The discarded uniform, like the offerings, are finished, done with; they’re not picked up and treated with reverence. They just enter the world in the same sense as a rooster’s beak, a dog’s foot, a flower… in this sense, they’re all the same. The objects that have importance at the time—the job in the military, the offerings—have a use, a lifespan, and then are just stuff. Actually, more interestingly, it’s the individual making those choices: the military officer putting on his uniform, the offerings being made, are just layered on top of one another. The same site is used again and again: the history is left, layered. It’s not packed up and put away. It’s dealt with, by the world, over time and time again.”

I asked myself whether my initial questions had by now been answered. Feeling a little overwhelmed, I asked Willy Leonardo, general manager of Seniman Industries, what were the most important lessons for him about working with Rodney?

He replied: “First, delegation, by which I mean understanding that individual success cannot be achieved without others and that if we have an initial idea we must share it and delegate responsibility to others. Second, that following up on the delegation and attention to detail is critical; no achievement is possible without this.”

This summary can apply to Rodney’s approach not only to business but also to art and life, there being little distinction for him between these usually separated elements.

And now I must return to the boots, where we began this story. They have taken us on a long and winding walk and prompted much thought and discussion. This in itself must be a key purpose for them, presumably for all of Rodney’s works: to stimulate us, to question our perceptions of how we view things, how we think of them, their functions, and how we see ourselves. Yes, we are “everyone” but we are also uniquely odd according to the dynamics of the forces running through us in a whirlwind of energies, which Rodney Glick has apparently learned how to harness in collaboration with others to produce such special results.

And I see that this particular story, this object, which took quite some time to research and write, is but one of the infinite number of possible stories that could have been written in a correspondingly infinite number of voices about an infinite number of objects in Rodney’s universe alone, let alone those that you might be composing as you read, as everything happens to everyone.

Author

Robert Finlayson moved to Jakarta, Indonesia in 2008, from Perth, Australia, where he had worked in the state government’s arts and culture department, managed literary NGOs and written poetry and short stories. In Jakarta, as well as managing Southeast Asian communications for an international agroforestry research-in-development organisation, he is collaborating in establishing a theatre community, Sanggar O, on the outskirts of Jakarta and researching a book about the spirit worlds of the region

Robert Finlayson moved to Jakarta, Indonesia in 2008, from Perth, Australia, where he had worked in the state government’s arts and culture department, managed literary NGOs and written poetry and short stories. In Jakarta, as well as managing Southeast Asian communications for an international agroforestry research-in-development organisation, he is collaborating in establishing a theatre community, Sanggar O, on the outskirts of Jakarta and researching a book about the spirit worlds of the region